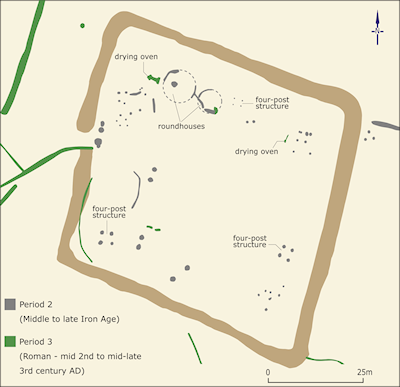

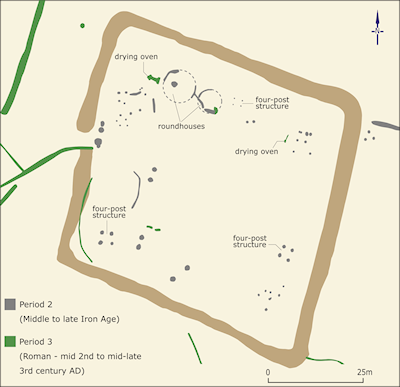

This site (Barber et al. 2006) started off in the Iron Age very much like Whitton as a four-sided enclosure measuring about 60m by 60m internally, although it was diamond shaped rather than square (Figure C). The surrounding ditch was similar in size - between 3m and 4.5m across at the top - and not quite as deep in its deepest part (1.8m) as Whitton (Figure D). The bank has completely vanished, but a strip of ground inside the ditch uninterrupted by any features shows that it would have been 3-4m wide. The main difference was the gate, which was simpler, with only one posthole at any time at either side of the entrance. Inside there were at least two roundhouses, four structures marked by four posts, and a couple with two posts. The roundhouses, one with a diameter across the roof of 6m and the other of 8m, were smaller than the ones at Whitton, and are marked only by the gullies made by water dripping from the roofs and wearing away the subsoil. Nothing survives of any wall structure: this may be because any supporting posts were in the upper levels of the contemporary soil and have now disappeared, but they may also have been like the Pencoetre Wood roundhouses, built of cob.

By the end of the Iron Age or the very beginning of the Roman period, this enclosure seems to have gone out of use, and the material from the bank ended up in the ditch, whether as the result of natural weathering, or because it had been deliberately pushed there. However, some earthworks must have still been visible at ground level, because when the site was reoccupied around the middle of the 2nd century, the new field system laid out in the area to the west of the enclosure respected it: some of the ditches connected with this field system drained into the enclosure ditch. Inside one corner of what was left of the enclosure, a typical Romano-British T-shaped 'corndryer' was dug into the ground, with a working area alongside it, probably covered (Figure E). Another, smaller flue dug into the ground may have belonged to another dryer. These dryers may have been for parching corn and malting grain, and some grains of charred spelt wheat found in it may have been among the crops processed there. Because this is just a working area, the living area of the settlement, with the houses, must have moved elsewhere, outside the area that was excavated. Activity seems to have come to an end some time after the middle of the 3rd century. In both the Iron Age and the Roman period, the site seems to have been of low status, since much of the pottery of both periods was locally produced and there is little in the way of decorated vessels. At any rate, even accounting for a shift in the living area of the settlement away from the enclosure, it is unlikely that the inhabitants were anything more than peasant farmers.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.