Cite this as: Teehan, M., Jones, R.H. and Heyworth, M. 2018 Three for One: Analysis of Three Differing Approaches to Developing an Archaeology Strategy, Internet Archaeology 49. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.49.12

As with the Musketeers, archaeology uses differing approaches in fighting for the greater good. Since 2015, three different strategies for archaeology have been developed by three separate organisations in three jurisdictions — Ireland, Scotland and England. Each had varied stakeholder-engagement foci but similar long-term ambitions. But unlike the Musketeers, none involved 17th century French aristocracy! The motivation behind each strategy impacted on who were the principle stakeholders: public, commercial, academic, state. Consequently, this affected not just the development and content of each strategy but also their implementation (which is ongoing). The following analysis will offer lessons to be learnt from stakeholder consultation, challenges faced and our thoughts on how best to implement an archaeology strategy.

The Archaeology 2025 Strategy: A Strategic Pathway for Ireland was an initiative of the Royal Irish Academy (RIA), and has been fully facilitated by the Discovery Programme. Both are all-island research organisations with a strong interest in promoting the value of archaeology to society. Archaeology 2025 was developed as a long-term strategy which is intended to inform policy and decision-making on archaeology and cultural heritage. The development of the strategy was based on consensus from local, national and EU levels both within, and outside of, the archaeological profession. It was launched by the Minister for Arts, Heritage, Rural, Regional and Gaeltacht Affairs at the Royal Irish Academy in May 2017 (Royal Irish Academy 2015). It is now being implemented by the RIA Standing Committee on Archaeology, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders on specific actions.

Scotland's Archaeology Strategy was launched by Scotland's Cabinet Secretary for Culture, Europe and External Affairs at the European Association of Archaeologists' Annual Conference in Glasgow in September 2015 (Historic Scotland 2015). It was an initiative set in motion by the then Historic Scotland (now part of Historic Environment Scotland), who established a Scottish Strategic Archaeology Committee comprising key areas of expertise across the sector to develop and drive forward the Strategy. Delivery of its key aims are through a number of lead bodies in partnerships across the sector.

In England, Heritage 2020 is a new collaborative strategy, launched in 2016 (Historic Environment Forum 2015), and aims to encourage collaboration and partnership to add value to the work of individual organisations across the historic environment sector. It is led by the Historic Environment Forum — the top-level cross-sectoral committee in England which brings together chief executives and policy officers from public and non-government heritage bodies to coordinate activities and to strengthen advocacy work and communications. Financial support from Historic England enables the Heritage Alliance, an independent heritage coalition, to provide a secretariat and the fundamental project management needed for developing and communicating the work of five working groups as well as support the Heritage 2020 Sub-Committee of the Historic Environment Forum.

So why now? Why did three differing jurisdictions, from three differing organisational backgrounds, decide to create archaeology strategies within three years of one another? Were we suddenly becoming fashionable or following a trend? Or did changing political, economic, societal and technical challenges require new approaches and solutions? These are certainly some commonalities that link all three strategies.

Economically, we are nearing a decade on from the economic collapse and resultant recession which had repercussions across the globe. In the UK and Ireland, it led to a decimation of the archaeological profession, including a reduction in state resources. One of the most extreme statistics is for Ireland, where there was an 83% exit from the archaeology profession between 2007-2014. The budget of the then Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht was cut by 44.6%. The UK hasn't seen quite the scale of reductions as Ireland, but the sector has considerably contracted and we have found ourselves in challenging and austere times. A report, Profiling the Profession, reported that the UK archaeology sector contracted by 30% between 2007-8 and 2012-13 (Aitchison and Rocks-Macqueen 2013).

Economically-driven issues affect political change most powerfully. In recent times of recession, archaeology dropped down the list of political priorities. For example, the updating of the National Monuments Act 1930 in Ireland was drafted in 2009. It was formally listed, along with other draft legislation, for discussion by the Irish parliament. It remains undiscussed on a 'low priority' list at the time of writing, eight years later. Similarly, in England, the draft Heritage Protection Bill was introduced in Parliament in 2008, but a lack of parliamentary time has meant that it did not progress and there are no indications that it will return in the near future. It is a political truism the world over that, in challenging times, sectors such as health and housing take precedence. However, it can also be accepted that politically sensitive issues such as archaeology in landscape planning can lead to a reluctance to deal with such legislation. One of the concerns within the archaeological community was that neglect of archaeology could be justified by political priorities in times of recession.

When it comes to a further challenge, societal, this has been affected by global issues such as climate change, food security, demographic shifts, health, wellbeing and migration. Whilst some problems existed for years, they have more recently been mainstreamed into public awareness (Figure 1). Society has been called on to be more responsible. As a result, societal challenges now significantly influence political priorities on local, national and international levels. They, in turn, have altered research frameworks and funding opportunities — areas critical to those of us working in the archaeological sphere.

Archaeology, as a study of the human past, has a contribution to make to such global challenges and to society. Acknowledgement, and the profession's promotion, of this fact is poorly understood. Archaeological research can help us learn and prepare for issues facing us in the future — analysis of past populations, their movements, their illnesses, foods and environmental experiences can inform how we address such societal challenges.

Technological changes have been nothing short of phenomenal, with the 'digital revolution' creating change on a par with the Industrial Revolutions. This scale of change can be alarming. What do these changes mean for workers? Disruptions in labour markets and migration play to the anxieties and fears of the masses, leading to some of the political upheavals of recent years (Bleich 2017). Society needs to find ways to harness this digital revolution for the benefit of all.

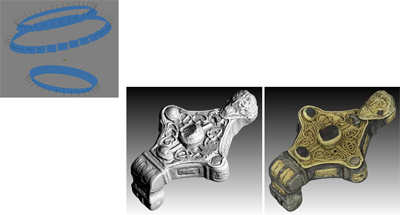

For archaeology, technological advances have opened many new portals and opportunities: these range from the availability of Geographic Information Systems enabling spatial analysis of data about the past through to digital accessibility of information through websites, apps and even games. More accurate methods of recording using global position systems have become commonplace and low-cost recording methods have facilitated greater public engagement. One example is a Discovery Programme 3D project involving local people recording ogham stones across the Dingle peninsula, using Structure from Motion (SfM) software on their own personal mobiles. The knowledge that is then created from technological methods can now be much more easily processed. This has transformed the working landscape for archaeology, and it opens the understanding of the past to potentially vast participatory audiences (Figure 2).

Various apps are being developed with the specific aim of delivering quality heritage information to vast audiences. In Scotland a new game, Go Roman, has just been launched as an app. This uses accurate digital modelling and reconstructions to open information about Roman sites (specifically the Antonine Wall, part of the Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site) to a young audience in a way that is familiar to them: through computer gaming. In England, the public can now enrich the national heritage list by adding images and anecdotes via an online portal, potentially sending information direct from a user's mobile phone whilst on site. The same is possible in Scotland, with apps specifically developed to enable 'citizen scientists' to upload information. A particular recent success was by the SCAPE Trust (Scottish Coastal Archaeology and the Problem of Erosion) getting local communities to upload information about specific sites around the coastline threatened by extreme weather conditions.

This is a further dimension which has played a huge effect in archaeology and the actions of archaeologists: the soaring interest and participation by the public in heritage in the UK and Ireland (Figure 3). This can range from participation and volunteering including collecting survey information to be shared with other, through to engagement with specific timetabled heritage events or purely through visiting historic sites and museums. National museums are frequently top visitor attractions. Yet supply and demand can feel out of kilter.

The alignment of working practices with new digital innovations, digital policy and public accessibility is becoming a more urgent issue daily. The benefits of non-intrusive investigation, conservation and increased information mining have yet to be realised. Support by funding agencies and decision-makers for both physical and digital archives can be dangerously underwhelming. Imagine a Bronze Age axe head. During its excavation, it is recorded and reported to the relevant authorities. It is analysed and specialists' results are issued. The artefact is then curated. Physical curation will always be an element of archaeology. Now archaeology also deals with 'born digital' data and the digitisation of collections. We are in a transition phase where access to research on the artefact is primarily done physically through paper archives and collections. The public benefit from increasingly exciting digital interactions in a museum setting. As the recording, curation and dissemination phases become increasingly housed in the digital sphere processes, guidance and infrastructural systems remain out of sync.

Growing concerns from the archaeology professions from economic, political, societal and technological landscapes in the UK and Ireland prompted the need to form shared plans of action in each of the three areas. In Ireland, the development of an archaeological strategy was in part a response to increased reports of archaeological site destruction and lack of penalty enforcement in a recovering economy supportive of the construction industry. Increased levels of volatility and volunteerism from a highly qualified profession also needed urgent addressing. But it was recognised that to create a strategy which has positive outcomes, engaging those outside of the profession who dealt directly or indirectly with archaeology was essential for change. Job creation is generally accepted as a primary political goal, and so Archaeology 2025 aspired to solve issues in the archaeology profession by appealing to governmental policies. In England, it was recognised that only a collaborative approach would help to add value to the work of single hard-pressed organisations which were often working to a shared agenda, but with reduced resources. In Scotland, specific challenges were recognised that needed to be addressed, whilst promoting greater collaboration and more public engagement in an era of competition for contracts and resources.

In 2014, the Europae Archaeologiae Consilium (EAC) held a pan-Europe conversation on setting a new agenda for archaeology. The result was the EAC Amersfoort Agenda (Schut, Scharff and de Wit 2015). Building on the practicalities of the 1992 Valletta Convention and progressing to embed the spirit of the 2005 Faro Convention in society were the key challenges for the future. In effect, this meant moving from challenges within archaeology to challenges for archaeology as an element of wider society. This includes the role of archaeological heritage in sustainable development. The EAC suggested that the Amersfoort Agenda recommendations be taken on at a national level. The stage was set for new approaches and strategies for archaeology. Could an archaeology strategy provide a rising tide to lift all boats? Recent findings from the NEARCH project (2017) show that 83% of Europeans believe supporting and developing archaeology is important for their countries.

Archaeology frequently falls within sustainable management in planning and economic development. All three strategies asked how can we make it fit into national political priorities? How do we mainstream into government and the public domain? We have already noted an increasing public appetite, whether through local community activities or heritage-based tourism. Research underpins sustainable management of our heritage, and is the key outcome for archaeology, whether conducted by the commercial sector, the state, universities and academic, or the third sector. All have vital roles to play, connections to make, information to share and stories to tell.

But development demands can lead to a disconnect between the large amounts of data generated through development-led projects and the very purpose of archaeology in creating knowledge and understanding of the past. Whilst the commercial archaeological sector has a greater ability and flexibility to expand and contract than the state sector, the state sectors have been contracting, compounded by re-structuring, placing a huge strain on resources. These three strategies have all put forward new ways in adapting to the realities of political priorities.

Government priorities in the UK and Ireland include building economic growth, rural affairs, infrastructural development, housing and promoting foreign investments — all with the potential to impact significantly on archaeology. In addition, in the UK, we have a whole raft of new challenges coming our way as a result of the 2016 Brexit referendum, some of which we are only beginning to recognise.

Even planning concerns have their own major issues. In Ireland, it is recognised that the current system forces corners to be cut. The UK is experiencing a rising trend of involving developers to a greater extent and concern over permitted development rights and the apparently unintended consequences of reforms to the planning system. Yet archaeological activities should be seen as an opportunity to add value and provide community outreach to development, following the ethos of engagement in the Faro Convention.

The interest in community or public archaeology is a growing phenomenon. Back in 2003, the Council for British Archaeology recommended the establishment of full-time Community Archaeologists across the country, to stimulate and guide public participation at a local level and exploit the current zeitgeist (Farley 2003). Whilst this had growing success, it has also been victim to expenditure cuts following the economic crisis. Projects funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund in the UK have a strong emphasis on public participation, given their strong focus on project outcomes for heritage, people and communities.

When it comes to tourism, archaeology is part and parcel of its raw material. In Ireland, the vacuum in national policy on cultural heritage has recently been filled with Culture 2025 and followed by the Creative Ireland programme, within which a national Heritage Plan has been promised. Cultural heritage is increasingly recognised as a factor in economic development and tourism. It is hoped this will be reflected in the forthcoming Fáilte Ireland ten-year tourism strategy. Archaeological images and stories of our past are core to 'Brand Ireland'.

In 2016, there was a spotlight on heritage in Ireland around the 1916 Easter Rising commemorations. Initial figures show an increase of over 16% in tourism figures for the first quarter of 2016 directly attributable to the centenary (Central Statistics Office 2016). The remembrances involved immense planning and cross-governmental organisation, with each recognising the benefits of partnership and shared responsibility. The political sphere has embraced this approach, and it is now embedded in implementation of new policy initiatives such as Innovation 2020 and Creative Ireland.

Archaeology 2025 has contributed to some of the above policies and it is hoped that it will continue to be a key reference document in the future. The consultation around the strategy also enabled fresh relationships to be established with the main tourism bodies, but also planning, agricultural and research bodies amongst others. Understanding what drives other sectors and disciplines and working on how archaeology can collaborate with external goals has been key to the strategy development.

In Scotland, we have government-designated 'Themed Years' which provide tourism foci, with 2017 designated as our Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology. One collaborative initiative is DigIt! 2017, a third sector led initiative by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and Archaeology Scotland with grant funding from Historic Environment Scotland and others. They received funding for a signature event entitled 'Scotland in Six' — celebrating Scotland's six World Heritage Sites alongside six 'Hidden Gems', voted for by the public. This was an event that ran from World Heritage Day in April 2017 through to Scottish Archaeology Month in September. But many other activities ran for the full year, and it is to be celebrated that we were successful in having a themed year with 'archaeology' in the title.

The attraction of active excavations for tourism is also a notable trend. In Orkney, the annual summer excavations at the Ness of Brodgar Neolithic site in the World Heritage Site Buffer Zone are a significant draw to tourists — this is referred to as 'The Ness Effect'. This is thanks to an excellent programme of engagement with the worldwide media in the immediate dissemination of findings (Gibson 2014).

2018 is the European Year of Cultural Heritage. Archaeology is part of cultural heritage. It will also mark global commemorations for the centenary of the end of the First World War. Scotland will have a themed Year of Young People. Ireland is looking forward to the Irish Free State 2022 centenary. Lots will be happening before the 2025 targets for both the Irish and Scottish strategies.

But archaeology is research, and it is this knowledge which underpins all management and public interpretation. Where there is a commercial potential, research is valued. Science, Technology, Engineering, and Maths (STEM) areas have seen an increased focus. Archaeology is in a unique position in that it acts as a bridge between the STEM sectors and the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences. As a study into the human past, its ability to contribute to both discipline areas is substantial. Because of this, a key strength of archaeology is its embedded need for collaboration. Opportunities for funding widen with imaginative partnerships and maximise the impact of archaeological knowledge creation and enrichment. The recent National European Research Area Roadmap, an offshoot of Innovation 2020, supports joint research initiatives and collaboration. Exciting opportunities are out there to undertake collaborative research and expand archaeological horizons.

Prior to 2015, England had the National Heritage Protection Plan — described as 'the business plan for the heritage sector in England' by the UK Government's Culture Minister. It was led by English Heritage, but was intended to be a sector-wide initiative with an external Advisory Board to oversee and help to guide its implementation. As the five-year Plan came to an end, the Advisory Board took ownership of what was to follow and, following an extensive sector-wide public consultation (which solicited over 1000 responses on the future priorities for the historic environment sector in England), the Heritage 2020 initiative was put in place. Initially, a framework document was drafted by a small group of individuals, looking at key achievements over the last ten years, and strategic priorities for collaboration over the coming five years in five different areas:

Working groups were set up to cover each of the five themes and, based on the initial framework document and further public consultation, working groups have defined action plans. Public consultation is intended to be an annual opportunity to allow everyone to offer an input, but working groups have a limited membership to ensure that the meetings are manageable. Organisations or individuals with skills / experience and resources to contribute to the action plan priorities can be identified and invited to join the groups as they move forward.

Working group members come together once a year, together with members of the Historic Environment Forum, to discuss a particular cross-cutting theme or topic which links all the working groups together. Most recently, issues and priorities relating to diversity were addressed. The Heritage 2020 Sub-Committee of the Historic Environment Forum will oversee an interim evaluation of Heritage 2020 in 2018 and make recommendations for its future development. The Heritage 2020 initiative is an attempt to focus on the strategic priorities where collaboration and partnership working can make a difference. This is even more important in a context of reducing public sector resources where all organisations are increasingly working under pressure due to limited resources.

In Ireland, the core challenge was that infrastructure and aspects of professional practice were in crisis. Maintaining the status quo was not an option. It was recognised that archaeologists could not solve all the issues being raised, and so consultation reached out to the matrix of people either involved with, or benefited by, archaeology. Transparency, inclusivity, fresh thinking and a future-focus were the principles which informed the engagement phase. Why do we need to change the direction of archaeology, and how do we create a sustainable pathway for the future? These were the driving queries for an extensive eight-month all-island consultation process conducted in October 2015 — May 2016.

Initially, representatives of the public, private and academia were consulted, using an online survey which reached two-thirds of the archaeological profession. This led to a discussion document which framed debate around key areas of concern. It also helped external stakeholders to understand archaeological issues and encourage their contributions. There was surprising positivity when engaging with those external to archaeology. The value of archaeology was widely acknowledged by external stakeholders, if not fully understood. Members of other relevant disciplines and professions, state bodies, local authorities, landowners, farmers, policy and decision-makers and experts in other countries all participated over the eight months of consultation. A significant outcome of this has been the building of new partnerships, rebuilding perceptions of archaeology and consensus on recommendations which, it is hoped, will ease implementation. Consultations developed around the constraints of location, travel costs and time availability to maximise involvement. In return, a broad spectrum of individuals and organisations across the island of Ireland, and from a local to European level, engaged. 181 individuals attended six events (Figure 4) and 110 organisations took part in the consultation process.

In Scotland, a review of the Scottish Historic Environment Policy led to a desire for a Historic Environment Strategy to be created. This comprised wide consultation across the sector and the resulting Strategy, government-led but adopted by the historic environment sector, was produced in 2014. The Archaeology Strategy, already in discussion following a review of the then Historic Scotland's archaeology function, needed to follow this initiative, and link to both it and the 2012 Museums Strategy, recognising that archaeology is important to both, and needed to provide a bridge between these two overarching strategies.

A Scottish Strategic Archaeology Committee was set up to develop and implement a strategy. Comprising mostly archaeologists with differing areas of expertise from across the sector, from local government to community archaeology and education, consultation on a draft took place in April to June 2015. During that time, over 200 people engaged in 25 workshops across Scotland, with targeted audiences ranging from museums to local volunteers. 73 written responses were received. These shaped the resulting strategy, launched in September 2015. The Strategy highlighted five key aims:

The Heritage 2020 framework document was finalised and the working groups established in 2015, but it needed the appointment of a programme manager, employed through The Heritage Alliance with funding from Historic England, to really help things to move forward. During 2016 the working groups met several times and defined their initial priorities. The key test comes during 2017 as the implementation phase really kicks in, and the working groups, with support from the overall Programme Manager, start to deliver progress on the issues they have identified. Already, the benefits of new collaborations and partnership working are beginning to be seen and this will be reported on towards the end of the year in a public 'annual report' which will be again be open to public stakeholder consultation to solicit wider feedback.

The Scottish Strategic Archaeology Committee used the consultation responses to formulate a Delivery Plan which was published in draft in September 2016 with a revised version in January 2017. Different organisations are leading on the five aims in partnership with others, including third sector Charities such as the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and Archaeology Scotland. The Chartered Institute for Archaeologists, who are a key stakeholder in the Archaeology Training Forum, lead on aim five — innovation and skills. Workshops have taken place between all the leads to discuss how to ensure the best way forward and avoid any duplication of effort, and other sector members are re-engaging with the strategy after the consultation period. There is no dedicated programme manager but the strategy is adopted by various bodies and is supported by the Archaeology team in Historic Environment Scotland, together with being used in decision-making for grants for HES' Archaeology Programme — over £1.4 million invested in archaeology per annum.

Implementation began for Archaeology 2025 after the ministerial launch in May 2017. It will be the most exciting, and challenging, phase. As it is led by a non-governmental body, driving the strategy will involve commitment, collaboration, time and motivation to achieve the vision. This was a key driver for conducting a wide consultation process. An oversight group has been established by the RIA as the strategy hub, with a part-time 'in-kind' strategy coordinator. Members of the strategy hub will be drawn from the current RIA Standing Committee on Archaeology, which has representatives from public, private and academic sectors. As a recommendation is worked on, this group will be supplemented by relevant expertise from cognate disciplines if needed. The document will act as a key reference for policy and decision-makers. It will be advocated as a 'cultural heritage' source document for the implementation of other policy frameworks, such as Creative Ireland. Such a collaboration can offer mutually beneficial outcomes between government and non-governmental agencies. It will be a key reference document in the development of the new National Heritage Plan by the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht in 2018. This is a significant development. Unlike Scotland's strategy, it does not have public funding directly behind the implementation. It relies on the time contributions of the RIA Standing Committee on Archaeology and others. However, this has resulted in an impartial strategy created from disparate voices. In the absence of direct government funding, an important method of implementation can be to feed into existing and future government policy.

All three strategies identified their stakeholder groups and sought to engage them both in the development of the strategies and in their delivery. Consultation has been important to ensure that initiatives are open / transparent and able to respond to the evolving issues facing the sector — regular consultations will allow initiatives to evolve as the external environment and the sector's priorities change over time.

Engagement and partnerships are key. Engagement can illuminate energy, release the drive by those eager to improve the ways that archaeology is practiced and resourced. But partnerships are necessary in seeing through delivery. Implementation of all three builds on the momentum of partnership initiated in their consultation phases to encourage communication, expand on collaboration with stakeholders and embed the wider value of archaeology. If we are to advocate for archaeology and use these documents as tools in that process, then they must be inclusive and demonstrate archaeology's value to society. Why should society care? Because it is about them and for them. Scotland's Archaeology Strategy had a section on defining our audience, noting that we wanted to be representative of all those who are or wish to be involved in Scotland's archaeology. It was recognised that our archaeological community includes people of all ages and abilities and is made up of paid and unpaid, university-based, public-sector, private-sector, third-sector, independent, local, national and international researchers (Historic Scotland 2015).

When it came to engaging with external stakeholders, it was important to break down 'perceptions of perceptions' and this became a positive outcome of consultations and engagement. An inclusive and welcoming approach goes a long way towards both participation and ensuring the partnership working necessary for delivery. But the challenge now is how to sustain momentum and deliver on the promises. Existing pressures of work on partnerships and a lack of capacity on an overstretched sector means that progress will be slow without dedicated resources. Heritage 2020 has a dedicated project manager. Archaeology 2025 will be driven by the Royal Irish Academy with part-time volunteer based strategy coordinator. Scotland's Archaeology Strategy has resources and funding from within HES, who are able to financially assist the sector in delivery, but the partners also need to allocate time and resources. Having dedicated programme managers does make a major difference.

From an Archaeology 2025 point of view, devolving responsibility to key stakeholders with the RIA steer direction is a good methodology where budgets for implementation cannot support a paid coordinator. In this implementation model, continued awareness and feeding the momentum will be key. For example, once a stakeholder achieves a recommendation, they are asked to use the Archaeology 2025 logo on their contribution. The risk with this model is that a certain amount of volunteerism, goodwill and enthusiasm is needed. It is also important to create priorities. Not all recommendations may be achieved by 2025, but energy should be strategically directed towards the most important. In the case of Heritage 2020 and Scotland's Archaeology Strategy, resources and dedicated staff are in place. In the case of the latter, it has the support of a government agency, Historic Environment Scotland. When resources are scarce, the lesson to take from it is to look to those who have them. It is hoped that Archaeology 2025 will inform government policy in the future, such as a national heritage plan, where government agencies will take action on key priorities for archaeology.

Implementation is both exciting and challenging. How do you execute a strategy in the light of available resources? Mechanisms to measure success need to be identified and can be challenging when some of the issues being tackled are long-term systemic concerns where no 'quick fix' is achievable. In this environment how do we sustain momentum and demonstrate 'value for money' to key audiences, particularly the Government? How to best review progress and report achievements? How do we mainstream what we do to the extent that we can get the positive messages out to the audiences who need to see them, especially the decision-makers? Again, partnership working is vital as it provides the opportunity to demonstrate that the sector has the commitment, collaboration, time and motivation to achieve our respective visions.

All three strategies were developed prior to, or during, the landmark UK Brexit referendum in 2016. Questions had been asked during the consultation phase of Archaeology 2025 in Ireland on how the strategy would respond to either outcome. While the recommendations made do not directly refer to possible consequences of Brexit, all three strategies much take cognisance of this in each of their implementation phases. Narratives around archaeology and cultural heritage in times of national identity change can become sensitive.

Dedicated implementation of strategies ensures that change will occur, even if not every recommendation and action has been ticked. But by focusing on agreed priorities, it may be that 'a rising tide will lift all boats'.

The authors would like to thank all those who developed and steered the respective strategies to this point. In Scotland, it is the Scottish Strategic Archaeology Committee, chaired by Professor Stephen Driscoll and all the various partners and collaborators. In Ireland, it is the Royal Irish Academy's Standing Committee for Archaeology, Chaired by Rónán Swan and colleagues across the sector, and especially the support from the Discovery Programme. In England, it is all the members of the Historic Environment Forum, the Working Groups and Historic England and the Heritage Alliance for their support.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.