Cite this as: Oniszczuk, A. 2018 Is Question-driven Fieldwork Vital or not? An Archaeological Heritage Manager's Perspective, Internet Archaeology 49. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.49.9

The Amersfoort Agenda formulated by the EAC (Europae Archaeologiae Consilium) after the 15th Heritage Symposium in 2014 acknowledges and marks the transition from the Valletta to the Faro Convention, from the technical aspects of mainly preventive archaeological research to the wider perspective of archaeology and archaeological research results functioning and embedded in society (EAC 2015, 16). Following further discussions and considerations in the years after (see EAC Occasional Papers vol. 10 and 11), during the 2017 EAC Heritage Symposium, a spotlight was turned on the issues of choices in archaeology and the need for explicit formulation of various selection strategies, varying from the most general national mechanisms of selection of archaeological sites for excavation, through research questions, to archaeological archives selected for permanent storage. In this context, the following article aims to answer one of the basic, introductory questions regarding the reasons for commencing any archaeological fieldwork.

Throughout the text, the question-driven fieldwork is understood as scientific, as opposed to preventive and development-led archaeology. The proposed division is based on the first impulse that drives archaeologists in the field, be it a need for knowledge or the need for clearing the land for future development. Research questions are of course also posed in the latter scenario. The truth is, however, that some data and resulting knowledge may be obtained even if archaeologists confine themselves to recording the site without in-depth consideration.

Analogies to the division I have proposed, and its related debates, may be found outside humanities. In natural sciences, it is reflected in the opposition between descriptive and hypothesis-based research. The former is nowadays perceived as inferior to the latter, which is seen as a sign of maturation of scientific disciplines (Casadevall and Fang 2008, 552). Can we say the same about archaeology? We too started from classifications and typologies but in the 1960s processual archaeology focused on explaining cultural systems, not just the objects. Regardless of all the criticism it received, processualism stirred up the waters and changed archaeology forever with the use of structured reasoning, computational techniques and theories adopted from other fields of science (Renfrew and Bahn 2002, 37). The 'loss of innocence', as David Clarke called it, was the prize for expanding consciousness (Clarke 1973, 6). In this context, the multifaceted image of archaeology that emerged from later discussions, aiming to explain the past rather than to simply categorise the finds, where theories must be tested on data, and proven to be their best possible explanations (Hodder 1995, 221), may be seen as an equivalent of hypothesis-based research. In natural sciences, advocates of descriptive research list examples of long-term applicability of some results, such as the work of Carolus Linnaeus or Dmitri Mendeleev (Engel and Grimaldi 2007, 646); archaeologists could definitely add Christian Jürgensen Thomsen to the list. The supporters of descriptive research also argue that development of any science is impossible without the influx of new data, especially the ones obtained with the use of advanced technologies. As Casadevall and Fang say (quoting Sherlock Holmes): 'It is a capital mistake to theorize before you have all the evidence' (Casadevall and Fang 2008, 553). The situation in archaeology seems to be even more favourable for recording and description as it is a science that destroys its own object of interest during intrusive research, therefore, making full repetition of observations impossible. Thus, also as far as new technologies are concerned, the development of archaeology is only possible with new observations.

To conclude these introductory remarks, development-led archaeology, which I am going to argue in favour of, is mostly descriptive, and regardless of the quality of the research and our personal preferences, research questions are secondary and necessity comes first.

The title question will be left hanging in mid-air for a while, because further discussion requires the knowledge of some data about Poland. Various features, except for its geographical location, situate the country in the middle of Europe. Firstly, it has a population of over 38 million and a surface of 312,679 km² (10th largest on the continent). Its size and population make it comparable to other big countries of Western Europe like Germany or France. However, the 26th position in the European ranking of Gross Domestic Product based on purchasing-power-parity (PPP) per capita in 2016 (based on WMF World Economic Outlook Database, April 2017) shows that, economically, Poland is still behind Western Europe and several Eastern European countries (Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Lithuania, Estonia). To some extent, we share experiences from the past with the latter, but the present is quite different. Needless to say, the economic situation of the country is relevant to the funds allocated to archaeological research.

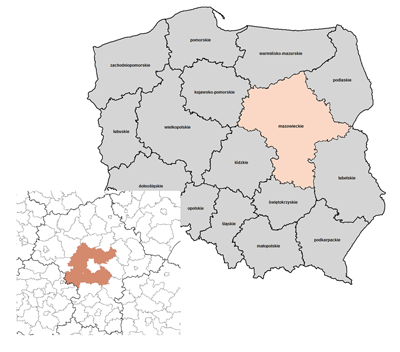

Poland is divided into 16 administrative regions called voivodeships. It is a unitary country, but regarding archaeological heritage management policies, individual regions have so far been quite independent. Today, Voivodeship Inspectors of Monuments and their offices remain within the structures of local government administrations — they are subordinate to their respective Voivodes who finance their offices and have the authority to appoint and remove them from the office. Whereas the General Inspector of Monuments (the Vice-Minister of Culture and National Heritage), while being personally responsible for heritage protection throughout the country, until recently had no real means of influence. Newly introduced amendments to the binding Act of 23 July 2003 on the Protection of Monuments and the Guardianship of Monuments do not alter this general structure but reinstate central coordination and control of the regional activities. These changes may, therefore, be a step towards uniformity and the much-awaited standardisation of regional policies and procedures in heritage management.

Poland signed the Valletta Convention in 1992 and ratified it 4 years later. It means that the document, which for Western Europe was in part a reaction in relation to the outburst of large-scale infrastructure developments and resulting destruction of archaeological heritage (Willems 2014, 152), came before the major modern Polish projects of large-scale preventive archaeological research. The first ones were the Yamal pipeline preventive excavations carried out in 1993-1998 (Adamczyk and Gierlach 1998, 18; Chłodnicki and Krzyżaniak 1998, 25) and the program of systematic motorway archaeological research that began in 1996 (Grabowski 2012, 76-7). The Faro Convention has not been ratified nor signed yet but preparations are in progress.

Archaeologists tend to complain about archaeology nowadays being just a service and not a scientific research, which is a fact, at least according to the Common Procurement Vocabulary (European Commission 2007). Used at European and national levels, it mentions archaeological research only twice: (1) as archaeological services related to architectural, engineering, and urban planning and landscape architectural service (no. 71351914-3); and (2) as excavation work on archaeological sites (no. 45112450-4) listed under, subsequently: construction, site preparation, and demolition and wrecking of buildings, earth moving. For many, these services are merely in function of the release of the land for future construction. However, as difficult as the position of development-led archaeology in the market economy is, while answering the title question I would like to refrain from grumbling. Instead, by analysing the situation in Poland from the perspective of the archaeological heritage manager, with the use of hard data wherever possible, and without windmill tilting, I will try to demonstrate how archaeologists can make the most of it.

Now, let us return to the main question…My initial positive answer was almost automatic; how could anyone object to such an implicit yet sound suggestion? After all, to quote Andrzej Abramowicz 'Fieldwork is the essence for archaeologists, field research with its highest form — stationary excavations.' (Abramowicz 1991, 118) (In Polish archaeological terminology, the term 'stationary excavation' was first used to describe any excavation larger than test trenches, but nowadays is understood as scientific, systematic research not rushed by upcoming construction). However, after only a moment's consideration, doubts started to emerge and my answer evolved, through a hesitant 'yes, but…' into the most definite 'no'. Now, on the contrary, I firmly believe that — whether we want it or not — development-led archaeology is vital.

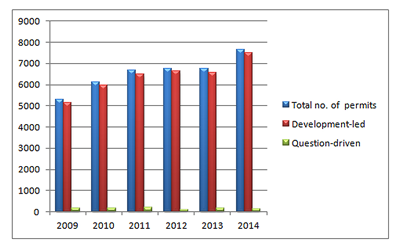

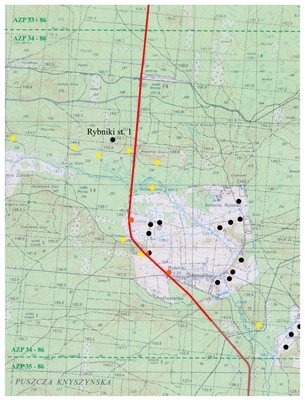

First of all, development-led archaeology is predominant. It has been shaping European archaeology at the highest level for several decades now, and, therefore, must not be considered inferior or secondary. Analysis of the number of permits to carry out archaeological research — issued in Poland by the respective Voivodeship Monuments Protection Officers and needed for any fieldwork — brings relevant data (Figure 1). Between 2009-2014, the total number of new permits grew from almost 5300 to over 7600 (based on archives of the National Heritage Board of Poland). It has to be noted that any changes in the decisions were excluded from the count because they did not affect the general character of the research. The number of scientific, question-driven archaeological projects, as could be judged from justifications for carrying out the research included in the permits, varied from 101 to 195 per year, which means that at the same time (2009-2014), contrary to the total number of archaeological fieldwork projects, the number of question-driven ones underwent certain fluctuations but generally decreased from c.3% to less than 2%. Development-led projects included all stages of preventive research, i.e. fieldwalking, test and preventive excavations. Question-driven fieldwork was more varied, not unexpectedly and included fieldwalking, verification surveys, non-intrusive research (geophysics and laser scanning), geological and geochemical probing, underwater survey, battlefields, exhumations by archaeological method (war graves, victims of communism), and excavations of sites endangered by illegal search and ploughing. The latter were subsumed beneath the question-driven research because various threats to heritage not related to any construction tend to be used instrumentally as a justification for the urgent need to excavate.

Development-led archaeology delivers massive amounts of data; hence, owing to its scale, it is also crucial for the development of archaeology as a science. Preventive excavations in Poland began in the 1920s. In 1922, during sand extraction in Krzemionki Opatowskie in Central Poland, one of the largest Neolithic flint mines was discovered. Three years later, in Końskie, a town in Central Poland, an early medieval burial ground was partially unearthed during construction of a roundhouse. Jerzy Gąssowski wrote that in 1924-1926 610 archaeological excavations were carried out, most of them preventive in nature (Gąssowski 2005, 9-10) and due to insufficient knowledge of archaeological resources, they were conducted in reaction to accidental discoveries and sometimes partial destruction of sites. Just as today, back then 'the works were characterised by nervous haste to keep the required time schedule in order not to hinder an investment or other economic activities' (trans. Gąssowski 1970, 214). Development-led archaeological projects were also carried out after WWII, but only the major pipeline and motorway projects occurred under Valletta. The Valletta Convention introduced the concept of archaeology communicating with society, and becoming 'involved in spatial planning and in the political and socio-economic decision-making' (Willems 2014, 151). The 'polluter pays' principle has been adopted into archaeology.

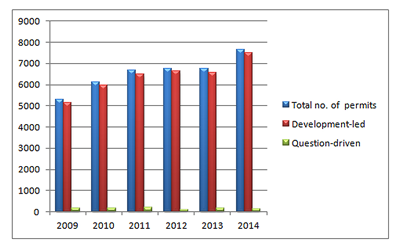

In Poland, the Valletta Convention has become a foundation for the entire system of development-led archaeological projects. For example. the Yamal-Europe pipeline archaeological research programme started in 1993. Fieldwalking of the entire route of the pipeline (684km) revealed 724 sites (Figure 2); 142 of them were excavated before the construction began, 166 during its first stage, and the rest (small sites of predicted low cognitive potential) were the subject of watching briefs. The total area under research was 45ha (Adamczyk and Gierlach 1998, 18). Archaeologists worked on 314 settlements, campsites and production sites, 28 burial grounds, and several rare pagan sanctuaries. The sites dated from Late Palaeolithic to early Middle Ages (10th-11th c.) (Adamczyk and Gierlach 1998, 20). The second programme — motorway archaeological research — began in 1996 and is still being continued. Its scale is much bigger, by 2012 the area under research was 1000ha (Figure 3). A total of 2500 archaeological sites were excavated including 2250 settlements, 200 burial grounds and 50 other sites, such as production sites, mines, and military relics (Kadrow 2012, 6; data of the National Heritage Board of Poland). Dating of the sites ranged from Late Palaeolithic to WWII.

The number of sites is large enough to demonstrate that development-led archaeology, carried out on a large scale, provides us with a statistical sample of the past. It may not be ideally representative, but definitely it is the best archaeologists can get. Of course, the choice of sites considered for research always depends on the current understanding of what archaeology is, especially in terms of the timespan it covers. In Poland, for example, late and post-medieval archaeology (14-18th centuries) truly became a subject of archaeological research only during the first half of the 1960s (Hensel 1965, 8). In 1944-1964, research of such 'late' sites amounted to slightly over 7% of the total number of excavations (Hensel 1965, 9). Comparable numbers for 1967-1998 can be obtained from the analysis of short notes on ongoing excavations published annually in Informator Archeologiczny (1967-1995). In 1967-1991, the number of late and post-medieval sites under excavation was c.21%, and in 1992-1996, 41% (median values). The growth in the latter period may be related to the fact that post-medieval phases started to be recorded properly. It also coincides with the formulation of the Valletta Convention, but this observation requires further investigation, especially regarding the credibility of available data. In 1996, the percentage decreased again to c.23 (the 1996 issue of Informator Archeologiczny was published in 2005. It was followed by 4 more issues. The publication finally stopped due to extremely irregular influx of excavation notes). Finally, archaeology of the contemporary past, the research of sites dated to the 20th century, is the latest archaeological novelty in Poland. It has been taken up systematically only in the 1990s (Zalewska 2016, 33).

This all means that, fortunately, this chronological bias diminishes as we get closer to the present, which can also be seen in the comparison of the pipeline and the motorway archaeological programmes. During the latter, archaeologists excavated the relics of WWII trenches and war graves and unearthed remains of the fallen soldiers. One of the basic premises of both programmes was to excavate all sites found on the trajectory of these two huge infrastructure projects, escaping political or personal bias. Now let us consider the influence of the latter on the basis of the numbers quoted above.

The authors of the source publication for the data from 1944-1964 (Górska et al. 1965) prepared a map of archaeological sites excavated in Poland during those two decades. In order to ensure its legibility, they mostly selected sites that were excavated systematically for several seasons and were partially or fully published. Preventive or unpublished research was only included if sites were of 'leading scientific value'. In areas where particular problems were better recognised — according to the authors, of course — the selection was even stricter and published sites of lower significance were excluded from the map (Górska et al. 1965, 17). Except for 1996, the editors of Informator Archeologiczny being the source for the data from 1967-1996, published notes firstly on all excavations and, later on, as the number of excavations increased, on 'regular, stationary' research (since 1991) or 'the most important' ones (1995-1996). These selection criteria may be understandable but such pre-selected data can only be published as they are. Any truly comparable re-use is impossible; the data do not render the full picture of archaeology in Poland between 1944 and the 1990s. They show what was considered important and relevant, and the relevance is what we have to be particularly cautious about. Let us remember that whoever decides on the relevance makes choices on the basis of the current state of knowledge and archaeological methodology.

The comparison of bulk data from the motorway research with other archaeological projects allows the verification of the efficiency of existing methods of site evaluation such as fieldwalking or test excavations. Let us take a closer look at some examples.

In 1998, during fieldwalking preceding the motorway preventive research, a site was discovered in Żyraków, a village in south-eastern Poland (Podkarpackie Voivideship). It was recorded as a typical, small early medieval settlement located along the old river bed, site no. 3 in the village. Between the houses of a modern village, archaeological remains were discovered. One year later the discovery was followed by test excavations: 8 trenches covered a surface of 90m². Based on the results, archaeologists determined the crescent-shaped extent of the site, 250m x 160m in size. They expected that the site may continue to the west but it was impossible to confirm this during prospection. Preventive archaeological excavations began in 2007. Jerzy Okoński, head of the research, wrote that if it had not been for the motorway archaeological research programme, site no. 3 in Żyraków — as typical and partially destroyed by houses — would have never been excavated; more particularly because in order to excavate this site, 10 houses, c.20 other buildings, garages, and several hundred metres of roads had to be demolished (Okoński 2009, 182-4). As a result, the settlement turned out to be at least 10 times bigger than expected, now estimated to 23ha instead of the initial 2.5ha. Eventually the research covered 1/3 of the total area of the site (Okoński 2012, 346). In 2007-2009, over 3230 features were unearthed, the chronology changed to late Bronze Age to post-medieval; and the work was to be continued (Okoński 2009, 181). The research provided also interesting data for discussion about the efficiency of prospection and test excavations. It turned out that two test trenches did not bring any archaeological evidence because they had missed the features by a couple of metres or just several centimetres (sic!). A further two had been positioned within a larger backfilled ditch so the feature itself had not been recorded. Thus, the results of the test excavations were misleading and the most interesting part of the settlement turned out to be located outside the predicted range (Okoński 2009, 184-5, photo 1-2).

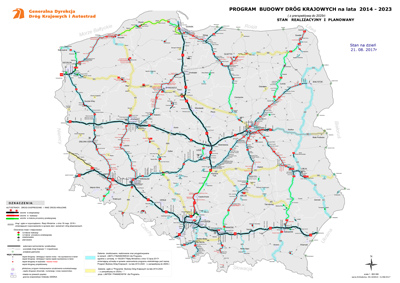

This issue of prospection efficiency (esp. fieldwalking) is particularly significant in Poland, where archaeological heritage management is based on the Polish Archaeological Record (PAR; Polish abbrev.: AZP) — a system of standardised recording of archaeological sites on the basis of their material remains visible on the surface known through fieldwalking or accidental discoveries. The PAR has been operative since 1978 and as of end of August 2017, the number of sites is over 452,000 (based on the archives of the National Heritage Board of Poland). We are aware of the limitations of fieldwalking as a method but hard data seldom appears. In this respect, again, the development-led research gives us the necessary insight. Michał Bugaj in his short study published in 2015 develops the issue of fieldwalking in forested areas. He presents an example from the Knyszyńsk Forest, north-eastern Poland (Podlaskie Voivodeship). Twenty two sites were recorded in the PAR in 1995 (Figure 4). Only one of them was located in the forest, having been discovered by a forester several years earlier, and not during actual prospection. In 2008, fieldwalking was repeated in preparation of the motorway preventive research financed by the General Directorate of National Roads and Motorways, and two new sites were recorded outside the forest (Bugaj 2015, 304-5). In the 1990s and 2000s, the area in question was also investigated by archaeologists from the National Archaeological Museum for scientific reasons. They discovered 14 new sites in the forest, some in the vicinity of the road (Bugaj 2015, 304).

Processing data from development-led excavations may be challenging but juxtaposing them with those delivered from other projects has a huge potential for heritage management. In comparison, during the programme of pipeline preventive excavations, the ratio of newly discovered to previously known sites was 3:1 (Bugaj 2015, 300). The settlement study in the Noteć valley (Wielkopolskie Voivodeship), an area particularly suitable for housing and recreation, revealed that when fieldwalking was repeated after 20 years, the area accessible for research was reduced, the number of new sites increased by 10-30%, and the presence of 21-25% of previously known sites was not confirmed (Dernoga and Starzyński 2006, 44).

The issue of the relatively low quality of development-led fieldwork is widely acknowledged, however, actual hard data is scarce. Let us refer, then, to a rarity — a recent study by Agnieszka Olech-Śliż and Mariusz Wiśniewski (Olech-Śliż and Wiśniewski 2016) who analysed the content of c.800 archaeological fieldwork reports from Central Masovia in search for the use of modern technologies (understood as the methods discussed during the Computer Applications and Quantitive Methods in Archaeology Conferences; the authors chose 20 of them). The projects in question were carried out in 2009-2014 in 9 provinces under direct supervision of the Masovian Monuments Protection Office (Olech-Śliż and Wiśniewski 2016, 191-2; Figure 5). They were almost exclusively (98.4%) development-led projects. The numbers gathered by the researchers are not overwhelming e.g. drones were used just twice, photogrammetry and ALS were employed once, and there were no cases of TLS (the latter may be justified by the lack of architectural remains). Geophysical methods and physico-chemical sampling and analysis were used 3 times each, and environmental sampling 12 times. No projects used a paperless archaeology approach, but it has to be noted that in Poland, legal requirements for excavation reports and documentation are still all about paper. Consequently, no research team delivered virtual and extended reality materials, and no project included online data repositories and data sharing. What is particularly noteworthy, even if some digital methods were used (orthophotography and GIS, 5 times; computer-aided drawing 133 times) only the printouts were delivered with excavation reports (Olech-Śliż and Wiśniewski 2016, 194-9). The situation is probably similar in other parts of the country; therefore, undoubtedly, development-led archaeology leaves plenty of room for improvement regarding the quality and standard of the research. I will sketch an ideal picture of such an improvement mechanism further in the text (see 4f).

An improvement (or sometimes a drastic change) is also needed regarding the cooperation with the general public. In the analysed fieldwork reports, for example, Olech-Śliż and Wiśniewski noted the lack of what they called 'experimental archaeology and re-enactment' (this category included also archaeological open days), yet archaeologists working in the studied area in 2009-2014 were engaged in re-enactment groups and participated in archaeological fairs and festivals (Olech-Śliż and Wiśniewski 2016, 197-8). Their personal interests, however, although still archaeological, did not permeate their working experiences. In this regard, and in reference to both the Valletta and the Faro Conventions, development-led archaeology, being literally closest to the people, is crucial for public outreach. Sending a proper message as to its meaning and value could help to overcome negative attitudes towards archaeology and raise people's appreciation for archaeological heritage.

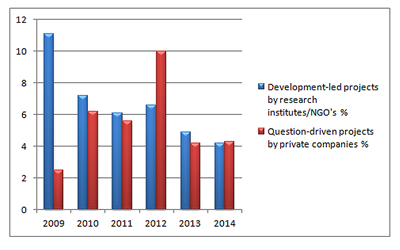

Perhaps not all the improvements can be done solely within development-led projects because of their character, mainly the intrinsic time pressure, but we could extend out to the wider archaeological community. In Poland, this community is relatively big (over 1000 persons reported within the DISCO project, see Liibert et al. 2014, 13) but divided, which can be observed in a changing profile of persons or organisations obtaining permits to carry out archaeological research. In 2004, 25% of all the projects were carried out by state agencies or research institutes i.e. universities, museums, the Polish Academy of Sciences. In 2008 their research amounted to 11.3% of the total and was accompanied by 3.2% projects that were carried out by various civic organisations like associations or scientific foundations set up to carry out archaeological research (data of the National Heritage Board of Poland). If we refer to the data previously used for 2009-2014 (see 4a), we will notice that the number of development-led projects carried out by state research institutes and heritage NGOs decreased from 11.1 to 4.2% (c.6% average) and the amount of question-driven fieldwork by commercial archaeologists was 2.5-10% (c.5%). (Figure 6)

These sharp divisions induced by the market economy do affect archaeologists' perception of their own profession — its character, goals, and methods — to such an extent that it might be argued whether Polish archaeologists can be perceived as one heritage community at all. The Faro Convention defines such a community as consisting 'of people who value specific aspects of cultural heritage which they wish, within the framework of public action, to sustain and transmit to future generations' (Art. 2b). Do all archaeologists value the same? Referring to the title question once again, let us consider for whom question-driven fieldwork is truly vital. Not for commercial archaeologists, who would most probably prefer to work only on interesting sites, but who need development-led projects to support themselves. Certainly not for heritage managers who would rather have sites preserved in situ and, above all, need standardised data with full spatial and chronological coverage. It leaves us only with scholars, employed in universities and research institutes, who carry out only 2% of all archaeological fieldwork in Poland but, as we can see, are the most influential.

I firmly believe that commercial archaeologists, scholars, heritage managers, and other archaeological sub-groups can all find their place within the system shaped by the dominance of development-led archaeology. Commercial archaeologists working under constant time pressure do not have time to experiment, and, to be frank, it seems really pointless to hold this against them. They will probably not develop new, breakthrough methods; what they need are ready-to-use workflow schemes, like checklists included in A Standard and Guide to Best Practice for Archaeological Archiving in Europe (Bibby et al. 2014, 44-50). Olech-Śliż and Wiśniewski pointed out that commercial archaeologists focus on achieving the legally required minimum (Olech-Śliż and Wiśniewski 2016, 201). Thus, archaeological heritage managers should work with lawmakers to increase those minimums, and ensure proper standards and guidance for archaeologists in the field. On the other hand, they should also cooperate with academia whose task within this framework would be to work out and test new methods. By nature, academia seems to be in the best position to use raw data from development-led research and basic studies of preventive research results for various syntheses. Incidentally, a few months before the publication of this article, a project entitled The Past Societies was finalised (see http://iaepan.vot.pl/en/projects-by-year/1618-the-past-societies-ang#characteristics). Its main goal was to rewrite the prehistory of Polish lands, on the basis of abundant new discoveries made mainly during development-led research amongst others (for results, see Urbańczyk 2016-2017).

It has been inferred already but regardless of all its limitations and drawbacks, development-led archaeology still seems to have the highest potential for systemic heritage management. Firstly, it ensures fuller spatial and chronological coverage than question-driven fieldwork. Secondly, it delivers bulk data which are indispensable in everyday practice of heritage management, because, contrary to a popular mantra of getting knowledge instead of data, we do need the latter. Legal obligations to carry out development-led research, and the resulting need for it to be structured and standardised, creates an opportunity of cooperation between heritage managers and large individual companies or agencies (in Poland: the General Directorate of National Roads and Motorways, EuRoPol GAZ S.A.) or entire business sectors (construction). Consequently, even in countries suffering from the lack of heritage standards like Poland, they can be created. The guidelines of the General Directorate of National Roads and Motorways, introduced in their first form in the late 1990s, are much more detailed than the legal minimum, and they are binding for all archaeologists carrying out research for this agency. Just as important, the cooperation with the broader world makes archaeologists leave their comfort zone and focus on translating heritage and archaeology to the public.

To conclude, development-led research is vital for the development of archaeology as a science. It is also indispensable for proper heritage management. Why then do we pose ourselves questions like the title, gently implying the expected and 'proper' answer? We keep repeating the mantra of getting knowledge instead of data, which again sounds noble, but maybe we are just tired. By using terms like significance or value, relevance and avoiding repetitiveness, we are trying to escape the overwhelming amount of data. When prioritising question-driven research, sometimes with a pre-selected list of questions (e.g. the archaeological research agenda in the Oxford Archaeological Plan; the National Research Agenda of the Netherlands (De Groot et al. 2017 etc.)), we assume that new discoveries may be only some variation of previous findings. What if we get an answer we have not asked for? Would every archaeologist armed with questions be open to it, especially if these questions were not of his/her choosing? I have already mentioned the pitfalls of relevance (see 4b), let me re-state: what is relevant now certainly was not relevant in the past and most probably will not be relevant in the future. And as for the 'evil' repetitiveness, everyday life is repetitive; various aspects of material culture in specific regions are similar and repeat certain recognisable patterns. How could we see them in archaeological sources if we cut out the repetitive and hunt for something new? If we are to create valid theories about the past, they have to be evidence-based. Although, of course, no interpretation is free from its interpreter, we should try to limit biases to a minimum. Equating valuable archaeology solely with question-driven research will bring, I fear, in the long run, a loss of information, unbalanced recognition of archaeological resources and will thus impede archaeological heritage management.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.