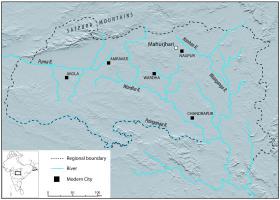

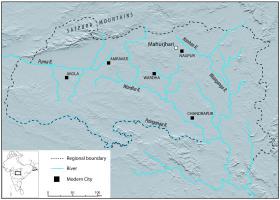

The archaeological site at Mahurjhari is located 15km north-west of Nagpur on the Nagpur-Katol road, Nagpur District, Maharashtra, India (79.006637° East, 21.221162° North), in the region of Vidarbha (Figure 1). The region is defined topographically by broad alluvial plains bordered by large hill ranges to the north, east and south. These plains are irrigated by a number of rivers, chief among which are the Purna and the Wainganga, together with its major tributaries: the Wardha, Kanhan and Painganga. Geologically, the entire region lies within the Deccan Traps, an igneous province of flood basalt, with large areas of lateritic rock and clay soils covering residual hills and river basins. Mahurjhari is situated in the north-eastern part of the region, within the Kanhan river basin, approximately 50km to the south of the Satpura Mountains. The immediate area, as with much of the region, features a wide variety of minerals including: manganese, coal, dolomite, white clay, yellow and red ochres, sand (stowing), quartz and quartzite. Indeed, the archaeological site at Mahurjhari is close to a particularly rich source of manganese, which is currently being mined (Mohanty 2003).

Discovered in the 1930s by G.A.P. Hunter (Hunter 1933), the site is characterised by a number of stone circles spread across a wide (c. 6km²) area, which in its broadest sense also encompasses the neighbouring site at Junapani (Rivett-Carnac 1879; Ghosh 1964, 32-33); a large (c. 20 ha) and conspicuous habitation mound located adjacent to the modern village of Mahurjhari, and a smaller (c. 10 ha) area of habitation located 500m to the south (Figure 2). Archaeological remains including potsherds, brick fragments, metalwork, sculptures and a large concentration of semi-precious stone-bead manufacturing debris are visible across the surface of the entire area (Figure 3). The site has been surveyed and excavated a number of times, notably by S.B. Deo who excavated a series of the stone circles and associated burials at the site between 1970-1972 (Deo 1973). Between 2001-2004, R.K. Mohanty excavated the area of historical habitation to investigate the bead-manufacturing industry (Mohanty 1999; 2003; 2004; 2005; 2006; Mohanty and Thakuria 2014; Thakuria and Mohanty 2009; Vaidya and Mohanty 2015). Together, the results of these investigations have revealed a complex sequence of activity and occupation at the site from at least the mid-first millennium BCE to the mid-first millennium CE and beyond — what, in India, is known as the Megalithic period or early Iron Age to the early historic period. For further discussion of the notation of periods in this region, see Shete and Kantikumar (2017), Shete (2018) and Sawant (2010; 2012). Those activities appear to have changed over time, with megalithic mortuary practices giving way to urban settlement and bead manufacturing at some point during the early centuries CE. During this time, the site and the bead manufacturing that took place there appear to have become increasingly important in wider regional economic dynamics (Sawant 2008-2009).

Unfortunately, our further understanding of the site has been hampered by a lack of chronological resolution in the dating of the main settlement, and a concomitantly poor understanding of the archaeological remains from the settlement. Addressing this, recent work has involved AMS dating of surviving radiocarbon samples that were collected during the most recent 2001-2004 phases of excavation (Mohanty et al. in press), as well as a re-analysis of the excavated pottery from the site. This article presents the results of the analyses of ceramics from the areas of historical settlement. We hope that the publication of the details of this pottery will provide a useful benchmark dataset for future investigations in the region. Moreover, in the presentation of our results we also suggest an alternative way of looking at and engaging with archaeological ceramics in India — one that is based on the analysis of the operational sequences, or chaîne opératoire, used in their production — in an attempt to move beyond certain traditional modes of practice.

Following a brief review of standard approaches to the study of archaeological ceramics from historical periods in South Asia, and the potential benefits that other analyses can bring, we turn to the assemblage from Mahurjhari and describe the methods that we have used to analyse it. This is followed by the presentation of our results, in two parts: first, a detailed description of the ceramic classes and variants that we were able to define and, second, their distribution across the excavated trenches and their seriation over time.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.