Cite this as: Van den Dries, M.H. 2021 The Public Benefits of Archaeology According to the Public, Internet Archaeology 57. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.57.16

National and international politicians and policy makers responsible for cultural heritage, including the domain of archaeology, consider this to be a driver of social and/or economic development. For more than two decades, (international) conventions, declarations and other policy documents have been expressing this; they increasingly expect and encourage citizen involvement in cultural heritage (management) and the empowering of marginalised groups through heritage (e.g. Council of Europe 2005). Even though it is acknowledged by national and local authorities, by heritage professionals and by scholars that citizen participation in heritage projects can indeed have a positive impact on local development and may contribute to the wellbeing and quality of life of those involved, it is not always apparent how to achieve this. For archaeology in particular, this brings along specific challenges. Owing to EU policies as well (in particular the Council of Europe's 1992 Valletta Convention), archaeology has evolved in most European countries into a predominantly development-led practice (e.g. Olivier and Van Lindt 2014; Stefánsdóttir 2018a). Moreover, this practice is increasingly contract-based and in various countries commercially operated. The question is how to create public benefits in such a development-led setting. This was the topic of the Europae Archaeologiae Consilium (EAC) annual heritage management symposium of 2020, held in Prague. Participants aimed to move the debate on archaeology and public benefit forward by discussing past experiences and future strategies. The main question addressed here is what actually the wider public considers and experiences as public benefits of (development-led) archaeology. What can we learn in this regard from (quantitative method) measurements of how archaeology affects people's life? There is further discussion on what these insights can tell us in terms of opportunities and unique selling points of development-led archaeology.

Like the wider heritage sector, archaeology increasingly needs to demonstrate its relevance to society. This goes for archaeology as an academic discipline, an applied professional sector, and as a heritage industry. Professionals active in these fields often experience this as a difficult task. This is particularly the case in the context of development-led archaeology, as the EAC's Amersfoort Agenda (Schut et al. 2015) and the discussions during the 2020 EAC annual symposium on heritage management once more highlighted. For the wider heritage sector, a demonstration of its societal values was captured in the Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe report (Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe Consortium 2015). It showed through quantitative and qualitative evidence of benefits and impacts that heritage represents a cultural, social, environmental and economic capital. However, the report does not provide much insight on archaeology as a specific component of the heritage industry and it does not mention development-led archaeology at all. It is therefore up to the archaeology sector to study and demonstrate the societal benefits of its academic discipline, of the professional applied sector and their subsequent heritage components (e.g. narratives, historical objects and heritage sites).

A major challenge for development-led archaeology, however, is that it is not its core business to demonstrate its (socio-cultural or economic) benefits for society. Its prime aim obviously is to save archaeological remains from being destroyed by infrastructural and building development or other ways of soil-disturbing land-use. Its prime product is the historical narrative of the place investigated, usually offered by means of an obligatory (technical) excavation report. Additional public benefits are mere side-effects, as in this development-led context it has proved a particular challenge to implement the Valletta Convention's article 9 on public outreach (e.g. Olivier and Van Lindt 2014). In the past decade, public participation in development-led archaeology has in several European countries thus remained an exception (for a Dutch example see Van der Velde and Bouma 2018) rather than a standardised practice (e.g. Stefánsdóttir 2018b; van den Dries 2014). There is thus little active citizenship involved in daily archaeological practice, in interpretation and in governance, maintenance and preservation.

For some professionals conducting development-led archaeology, this knowledge generation represents the main and only public benefit of their work. For them, archaeology does not have (or need to have) an additional social or economic impact on the community. They may not even have any clue how their work can in practice contribute to (local) sustainable development or any other societal goal (international) policy documents express. However, the Amersfoort Agenda (Schut et al. 2015) and the discussions during the 2020 (and former) EAC meetings demonstrated that a growing number of professionals, together with development-led practice, do aspire to do more than simply disseminate the knowledge generated. According to their representatives present, an increasing number of responsible national heritage boards and state agencies aim to comply with the Faro Convention principles and encourage people to participate in research activities and to benefit from archaeology in terms of sustainable development (see other contributions in this issue). There is, however, still a need to better understand what the public benefits of archaeology exactly are or can be, and how to generate such benefits in a development-led daily practice (see also Stefánsdóttir 2018b).

As stated, a similar comprehensive, Europe-wide value assessment like the Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe report (Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe Consortium 2015) unfortunately does not exist for archaeology. Hitherto, the only Europe-wide and elaborate public survey on the values of archaeology was conducted in 2015 by the NEARCH research project, which was funded by the European Commission within the framework of the 'Culture Programme'. It included a statistically representative sample (a total of 4516 adults, age 18 and older) from nine European countries (England, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain and Sweden). This survey (for details see Kajda et al. 2018; Martelli-Banégas et al. 2015; Marx et al. 2017; Van den Dries and Boom 2017) and some case studies on community engagement that were carried out during the NEARCH project (2013-2018), offer valuable insights on public benefits that may also be of use for the practice of development-led archaeology. They show what members of the public consider the benefits of archaeology and how they think it affects their life. Some of the insights it generated will be discussed below as they may inspire and support professionals to further increase the benefits of development-led archaeology for society.

The NEARCH survey made clear that across Europe, members of the public seem to consider archaeology first and foremost an academic endeavour (69%). We saw some difference between individual countries regarding numbers, but without exception all respondents primarily associated our profession with the production of knowledge, mostly generated by experts (from universities, public research institutes or museums). The role of archaeology mentioned most often is 'to pass history down to younger generations' (47%), so to tell stories. This was also reflected in other surveys in The Netherlands, which showed that the public's prime motivation for participating in archaeology is the wish to gain knowledge, to learn about these stories (e.g. Van den Dries et al. 2015; Van den Dries and Boom 2017). For instance, in a public survey that our Leiden University students conducted prior to a community excavation in Oss (Netherlands), a majority (68%) of the respondents expressed that if they would join the dig, they would do so for educational reasons (Van den Dries et al. 2015, 227). Moreover, in a case study in Landau in der Pfalz (Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany), where we explicitly asked survey respondents who had visited a Neolithic house reconstruction about the knowledge they had gained, an overwhelming number (101 people out of 106) said they had learned something new from their visit (Boom et al. 2019, 37).

Apart from 'gaining knowledge', other benefits of archaeology seem much less obvious to the public. In the NEARCH survey very few European citizens linked archaeology to, for instance, social and economic values. Only 8% think it contributes to identity building and 6% indicated they think archaeology contributes to local sustainable development. Even less (4%) think it adds to quality of life, and also 4% consider it a leisure activity. Participating in the community excavation in Oss was not immediately connected with wellbeing benefits either (Van den Dries et al. 2015, 227). In the eyes of the public, archaeology thus does not add much to a wide array of public benefits. They probably do not connect such benefits to the particular practice of development-led archaeology either, as it turned out that not many people actually know how archaeology in contemporary society is organised. Only 10% of the survey respondents said they were familiar with the concept of development-led archaeology.

To what extent the public experiences (or expects) an increased knowledge about archaeology as also having a direct impact on their life or wellbeing, is not clear. To my knowledge, this has not been evaluated by means of a representative, transnational quantitative study. There are, on the other hand, some indirect indications that suggest the public may not rate such benefits or impacts very highly for them personally. For example, the respondents to the NEARCH survey did not demonstrate a strong personal connection with archaeology. While 91% say archaeology is of great value and an advantage for a town (86%), and 85% would want to visit an archaeological site and 70% had done so, a much smaller number (54%) said archaeology is a field for which they feel a personal attachment (Figure 1). Among younger people (18-24 years of age) this attachment is even less (40%).

This limited personal attachment is also reflected by the fact that 73% of the NEARCH survey respondents think archaeological research is mainly carried out by staff members of universities, museums or public research institutes; a much smaller number (55%) think of amateur archaeologists. Among young people (18-24 years), the number of respondents who think of amateur archaeologists is even smaller (41%). A majority of the public thus associates 'doing archaeology' with experts; they do not immediately think of it as a leisure activity or a voluntary job for themselves.

A third indication of archaeology literally being at 'a distance' to members of the public is reflected by another interesting figure from the NEARCH survey. When the participants were asked to indicate the era of their main interest (on which they would want to visit an exhibition), 'antiquity' received the largest number of votes (selected by 36% across Europe, to over half in Italy and Greece); 'archaeology of the contemporary era' the smallest (7%). This suggests the prime association of the concept of 'archaeology' is with a more distant past and with 'antiquity'. Many members of the public do not immediately think of archaeology as a source of information relevant to their own past or heritage. Moreover, it has been observed in various studies with small local groups of Dutch residents that the public usually connects the act of excavating primarily with doing (or expecting) spectacular and important discoveries (e.g. Wu 2014, 51; Bosman 2019; Schneider 2020).

The fact that members of the public across Europe do not immediately associate archaeology and participating in archaeological activities with personal benefits other than gaining knowledge, does not mean there are none. For instance, Fujiwara et al. (2014) demonstrated their existence in the United Kingdom (defined as 'primary benefits' for individuals' wellbeing and 'secondary benefits' for employment, tourism etc.) through statistical analysis. The UK's Heritage Lottery Fund and Historic England (Reilly et al. 2018) have shown positive evidence as well. We also know from our own case study research at Leiden University that social benefits like increased social cohesion can be generated with people who participate in archaeological activities. For example, in the community dig case study of Oss (Netherlands), a quantitative survey among potential participants showed 30% would join the excavation for social reasons. They liked the opportunity of doing things together with other people and to strengthen social cohesion with neighbours (Van den Dries et al. 2015). Moreover, 60% expected that joining a community dig would yield personal benefits, like meeting other people with whom they share the same neighbourhood.

The case studies that were included in the NEARCH project showed furthermore that activities that actively engaged participants (e.g. the You(R) Archaeology art contest and a city tour revealing Invisible Monuments via a mobile app) had high impacts on positive emotions, like feeling relaxed, inspired and healthy. Such activities had in fact higher impacts than, for instance, a more passive visit to a fancy exhibition (e.g. the DomUnder exhibition in Utrecht, Netherlands) (Boom 2018, table 6.11). Active participation in the first two public activities let participants report a 3.6 for feeling energetic and a 3.5 for feeling happy (on a scale from 1-5, with 1 being low and 5 high). The more passive DomUnder visitors reported a 2.6 on happiness. Even though 'feeling healthy' had on average the least impact (2.6) out of a total of nine positive emotions that were measured (seven for DomUnder visitors), this was still considered a serious positive effect – and in any case surprising - as these activities had not explicitly aimed to affect the participants' feelings regarding health at all. It also needs to be noted that we did not give the participants a definition of 'health'. Maybe if we had provided the definition of the World Health Organisation, according to which health 'is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity', the scores might have been even higher, as our participants presumably only considered the physical and/or mental aspect, not the social.

These case studies also showed a variation from one activity to the other as to which emotion got the highest score on impacts that people experienced. For example, the participants of the Invisible Monuments activity felt the strongest impact on their health. Boom thought this could relate to the fact that the activity involved some physical exercise (Boom 2018), as they walked or biked from one historical site to another in the Greek city of Thessaloniki (http://www.nearch.eu/news/invisible-monuments; Theodoroudi et al. 2016). Participants of the You(R) Archaeology art contest felt most impacted on feeling inspired and capable (Boom 2018), which probably related to the creative nature of the activity.

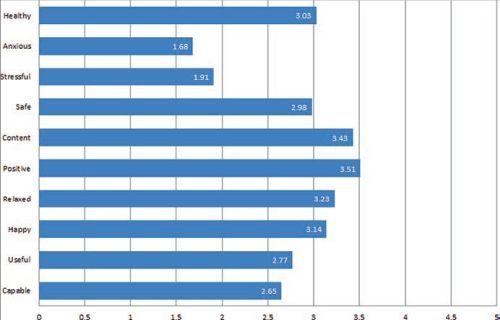

We found comparable testimonies of wellbeing benefits in other case studies as well. For instance in the community excavation in Oss (Netherlands) we asked participants to appraise their participation afterwards and 11 out of 12 respondents said the activity had been good for their wellbeing/health (Van den Dries et al. 2015, 230). The same was the case with visitors to the Neolithic house reconstruction in Germany (Landau in der Pfalz). Even though the visitors' engagement with this prehistoric representation consisted mostly of passive information processing and little physical activity (e.g. doing things manually), they nevertheless reported surprisingly high socio-cultural impacts with this encounter (Boom et al. 2019). A majority said they experienced positive feelings, such as being 'content', 'relaxed' etc. (Figure 2). Three-quarters also indicated their visit had contributed to feeling happy and healthy.

It thus seems apparent that participating in an archaeological activity can generate social and wellbeing benefits, but the public may not yet realise this.

On the basis of the benefits that most members of the public spontaneously associate with archaeology, and those that have been measured, an apparent imbalance can be noticed. The public's focus on knowledge gain as the prime and almost single benefit suggests there is a mismatch between the expected benefits as expressed in policy documents and those the public acknowledges. This implies that if archaeology wants to 'sell' its development-led practice as an endeavour that yields social public benefits or adds to individuals' quality of life, some work needs to be done. One should in any case make contemporary archaeological practice better known to the public, as well as its (potential) benefits for society. With regard to the possible values and public benefits of archaeology, there is a growing body of literature showing what these are. What seems to be most difficult within the context of a development-led practice, is to think of opportunities to capitalise on these values and to put them into practice. I will therefore focus on this in the remaining part of this article, by discussing what we can learn from the public's testimonials in terms of opportunities for development-led archaeology to put its public benefits into practice and what its unique selling points may be.

A first valuable insight is that a relationship could be seen between the level and kind of benefit that participants report on, and the kind of activity (the nature of the engagement) that was being offered. If one offers, for example, activities with a focus on education rather than on entertainment, social cohesion, or on individual wellbeing, education is subsequently the aspect that is impacted most. This sounds logical and may exactly be the reason why most people associate archaeology primarily with producing knowledge. It could very well reflect the focus of the activities or engagement the public was hitherto offered most often. The same goes for the public's fascination with important discoveries (for the Netherlands see for instance Bosman 2019; Schneider 2020; Wu 2014) which presumably reflects what the public is being exposed to the most. Important finds and their academic value is what is usually heard and seen in the media - at least in the Netherlands (e.g. Barel 2017; Bosman 2019, 56) - and which in Europe is usually the main source of information on archaeology for members of the public (Martelli-Banégas et al. 2015; Marx et al. 2017).

Such a perception of archaeology may seem like a disadvantage to the daily development-led practice, which does not exclusively yield the big stories. However, this cause-effect relationship also creates opportunities. It implies that one could further achieve other societal benefits, like wellbeing, by doing things differently, by offering purposeful and dedicated activities that put an emphasis on such benefits.

One of the unique selling points, and thus opportunities, is that development-led archaeology is an active, outdoor activity. This is exactly to what we attributed some of the positive impacts on wellbeing that people reported on, such as in Landau (Germany) where a Neolithic house had been built in a garden as part of a large horticultural show. It has often been claimed that doing activities outdoors or being in a natural environment can be good for wellbeing (for overviews of relevant sources see for instance Carpenter and Harper 2016; Mansfield et al. 2018). The same was said for community archaeology projects in the UK (e.g. Simpson 2009). It is in any case increasingly being recognised, across the discipline and beyond, that various types of archaeological activities can be useful for improving mental, physical and social wellbeing (e.g. Darvill et al. 2019; Reilly et al. 2018).

The positive effects that participants mentioned in the Landau survey made us recommend offering more outdoor archaeological activities or to connect archaeology with existing outdoor activities (like a horticultural show), if one would like to contribute to wellbeing benefits (Boom et al. 2019). Development-led archaeology seems to be a perfect candidate to offer such activities. Even though partaking in archaeological fieldwork surely differs from experiencing the look and feel of a life-size Neolithic house, and may not generate identical effects, it is inherently an active and (social) outdoor activity. As such it is likely to contribute to feelings of wellbeing such as those reported by our survey participants.

However, as there will be little or no direct impact from encounters with the historic environment on people's lives without participation, barriers to access need to be broken down if the archaeology sector aims to increase its relevance and benefits for society (see also Reilly et al. 2018; Monckton this issue). The NEARCH survey indicates there are possibilities to do so. A majority (61%) of the European citizens expressed an interest in taking part in an archaeological excavation. Some 51% were interested in getting involved in the decision-making process of a nearby archaeological project. It is actually a recurring pattern that survey respondents express an interest in getting more actively involved in archaeology. Various public surveys conducted in the Netherlands all showed that there is still a considerable group of potential participants for archaeological activities (see Van den Dries 2019 for more details). Only small numbers of respondents indicated not being interested in archaeology or in visiting sites; in the NEARCH survey this was only 10%. Moreover, as archaeology usually means 'digging' in the eyes of the public (e.g. Martelli-Banégas et al. 2015; Bosman 2019, 103), development-led archaeology in particular seems to have a huge volume of potential participants.

In this context it should also be mentioned that in the participation projects the NEARCH project studied (DomUnder, You(R) Archaeology and Invisible Monuments), Boom noticed that in some activities older people seemed to be impacted less than their younger fellows (Boom 2018, 160), except when they participated in volunteer work. Volunteering had a strong impact on their feeling of social cohesion (Boom 2018). Boom thought this lower receptiveness to impact could relate to the wider experience older people already have. Moreover, in some other surveys, seniors (60 years and above) turned out to be less enthusiastic about the idea of getting involved in the actual fieldwork during excavations (e.g. Martelli-Banégas et al. 2015; Van den Dries et al. 2015). This is again useful information in the context of development-led archaeology; while public outreach activities in archaeology often address either children or senior members of the public, it is worth the effort to try to engage young people (young adults) more, as they are more interested in excavating and generate a higher social return on investment.

Regarding costs and the (social) return on investment, an equally interesting result was noticed with our three case studies, namely that public benefits could be achieved at a relatively low cost. In fact, participants in less expensive activities (like the art competition) that were conducted during the NEARCH project reported higher impacts on some personal benefits than those involved in the more expensive ones. Krijn Boom therefore concluded that it is not the financial input, but rather the goal and nature of the activity, together with the receptiveness of the audience, which seem to determine its impact (2018, 179). This could be another valuable insight for development-led archaeology, which usually does not generate a high budget for outreach and participation activities. Low-budget activities could in principle be more easily conducted during a (short running) development-led project than an expensive and time-consuming fancy exhibition.

In sum, it could be considered an inherent quality of development-led archaeology that it is a creative and active outdoor endeavour, in which people gain knowledge and strengthen social bonds through close collaboration. A chance to experience this could in principle be offered to a wide and diverse audience at a relatively low cost by encouraging local (young) people to participate in (co-created) low-budget ordinary activities or just in the daily on-site routines. This combination of circumstances and values is exactly its unique selling point which development-led archaeology may turn into its societal capital.

While the survey data and case studies that I based this article on revealed opportunities for development-led archaeology to increase its public benefits for society, they illustrated some challenges as well. The main challenge is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to achieve benefits for the public. The NEARCH public survey and presentations at EAC meetings (and their publications) show a high level of differences in what members of the public do, need, expect and appreciate across Europe. There are also huge differences between gender groups, age groups and socio-professional groups. Things that work for one country or one target group (gender, age category, socio-professional category), may have no (or the opposite) effect on another. This implies that one needs tailor-made approaches. To be successful, one thus needs to be willing to work seriously on public benefits. It should not be an afterthought. One needs to have a genuine interest in the public, in involving (under-represented) target groups and in addressing their needs. Moreover, one needs creativity to be able to recognise and subsequently utilise the opportunities for engagement of a project at hand. In short, a successful outcome requires a dedicated and professional approach. It also implies that this kind of labour should be valued and appreciated – and rewarded in terms of salary - (at least) equal to the other tasks that need to be carried out during a development-led project. If public engagement work is not valued more positively among academically trained professionals than hitherto experienced in academia (e.g. DelNero 2017; Maynard 2015; Watermeyer 2015), it keeps having a lower status and low priority in comparison with other tasks. This may keep public engagement in archaeology from becoming a more popular activity (see also Van den Dries 2015) in which staff members would like to gain expertise and maybe specialise.

Another challenge is closely connected with the former and concerns the issue of professionalisation and gaining knowledge. For development-led archaeology to be able to also operate as a 'heritage industry' producing more societal benefits than it has done to date, it needs to better understand public benefits and how they can be achieved with various, so far under-represented, groups. We also need to learn how long any of these impacts last and what exactly the benefits in the long term are. We furthermore need to know if there could be potential negative impacts as well; if one target group benefits, could this have negative impacts on others?

We therefore need to keep conducting surveys, impact assessments and evaluations of participation projects. Studies like the NEARCH public survey have already proven to be highly appreciated and valuable - its results were mentioned by several participants during the 2020 EAC meeting - but we also need evidence from the field. The number of community archaeology projects is growing slowly but unevenly, and with the usual target groups. Moreover, these projects hardly operate within a daily practice that is primarily development-led and commercially operated, with some exceptions (e.g. Van der Velde and Bouma 2018). We thus need to learn from best practices in this context as well, in order to assess options, approaches and opinions from professionals and experiences from participants. Policy makers, both at the national and international level, should strongly encourage (and grant funds) to collect such data in a (commercially operated) development-led context, not least as it would also better ground and justify the claimed heritage values in current policies and their calls to mobilise cultural heritage as a driver of public benefits.

In various European countries, most members of the public consider archaeology first and foremost an academic endeavour (Martelli-Banégas et al. 2015; Kajda et al. 2018). In their eyes, archaeology is the domain of experts and primarily concerned with the production of knowledge about a long-vanished past. Survey participants indicate they hardly consider archaeology a leisure activity and they do not yet associate it with social or economic benefits. Moreover, it does not seem to be considered of importance for their own (quality of) life or (mental) wellbeing. However, when we include participants in activities and measure effects, for instance on social cohesion or wellbeing, many more benefits come to light. Archaeology can add to wellbeing and quality of life, and has opportunities to do so on a larger scale, even in the context of development-led archaeology. Thus archaeology does not need to be humble about its values and benefits for society.

However, if development-led archaeology projects wish to amplify their relevance for members of the public and have an impact on people's life, some work needs to be done. It turns out that this specific branch of archaeology, in particular its specific circumstances, is not very well known among the public (nor with policy makers and heritage researchers either). Moreover, it is also not the prime aim of development-led archaeology to have a local social or economic benefit for the public. This makes it difficult for development-led archaeology to demonstrate or further elaborate its public benefits. It implies this industry needs to open up further and encourage more active participation by a more diverse audience, as without participation there is presumably no direct impact on people's lives at all. The good news is that there are opportunities to do so if we look at it from the perspective of the public; the NEARCH survey revealed that a majority (61%) of the respondents across Europe have an interest in taking part in an archaeological excavation. It therefore seems to be first of all up to the authorities, policy makers, developers and archaeologists to make it happen.

I would like to thank the organisers of the EAC meeting in Prague (2020) for inviting me to give a paper. Such meetings and its discussions are mutually beneficial and certainly informative for further developing university training and educational policy.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.