Cite this as: Hurley, M.F. 2021 A Case Study in Archaeology and Public Benefit from an Urban Excavation in an Old Brewery: Cork City, Ireland, Internet Archaeology 57. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.57.5

Redevelopment in Cork, Ireland's second city, revealed evidence for 950 years of urban development, from the Viking Age to the Brewery that closed in 2009, and initiated a much-needed boost for a declining city centre. The new development proposals for the site occasioned the first large-scale urban excavation in Cork since the economic crisis of the preceding decade. The inherent challenges presented by such a site in a recovering economic climate were offset by the scale of the opportunities for excavation and knowledge advancement in what has long been recognised as one of the oldest parts of the city. Public interest and sentiment for 'old Cork' ran strong and the unfolding situation was closely followed.

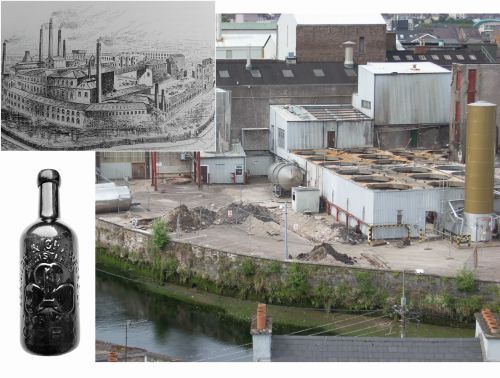

The area enclosed by the medieval walls of Cork is well documented and afforded legal protection under the National Monuments Acts, Ireland's legislation for protecting and preserving historic and archaeological heritage. In 2009 the old Beamish & Crawford Brewery in Cork came up for redevelopment and heritage was immediately flagged as a critical issue, since the brewery was founded in 1792 within the most historic part of the city and had expanded over the years to occupy about one-third of the medieval core. In addition to sub-surface archaeological potential, two historically documented monuments were known to have once stood on the site; the medieval town walls lay close to the southern and western boundaries and the site of St Lawrence's Church was attested to by historic maps. Archaeological excavation that had taken place on adjacent sites since the 1970s showed that cultural layers from at least the early 12th century onwards were a feature of the area and these were generally represented by well-preserved organic materials made in the Hiberno-Norse (late Viking Age) tradition.

Some of the brewery buildings themselves were highly regarded, with the Tudor-style 'counting house' (administration building) having an iconic status as a symbol of 'old Cork', notwithstanding its comparatively modern construction (1920). Above all else, Cork people were strongly attached to the traditional brand (Beamish stout), which contributed to the identity of the site as a local landmark and part of Cork's character (Figure 1).

From the outset it was agreed that public benefit should be a significant element of any proposal; a partnership of Heineken and BAM Ireland were the initial developers. An Events Centre (concert arena/venue centre) had long been identified as lacking in the economic and social growth of Cork and a proposal was developed putting the site forward as a suitable space for this.

The historic buildings in the central part of the site were to be retained and refurbished, albeit considerably enlarged and modified within the historic fabric but nevertheless preserving in situ much of the sub-surface area. The greatest initial commercial viability was the creation of four newly built blocks of student accommodation, in part above a basement car park.

Archaeological testing in 2010 revealed that sub-surface coal bunkers, basements and modern services across much of the site had greatly compromised the site's archaeological potential. The northern central part of the site was considered to be the least archaeologically sensitive and therefore suitable for the development of a basement. By contrast, the street fronting area had seen little impact; the archaeological strata there were well preserved. In situ preservation of the street-fronting sub-surface was to be achieved by a foundation design based on a widely set pile-grid. The excavation of one area at the street front was of course necessary to provide access to the basement and this strip was initially the main focus of the archaeological excavation.

The main excavation began in November 2016 and was completed in June 2017. Thereafter, the excavation ran in tandem with the construction process until November 2019.

The most significant findings were a sequence of house floors dating from c. AD 1070 (the earliest so far recorded in Cork) to c. AD 1200, but with little structural evidence for the 13th to 17th century period (mostly represented by pits and other sub-surface cut features), and then the stone foundations of 18th-century houses and laneways. The ground plan of the mid-12th century church, initially dedicated to St Nicholas and subsequently altered and rededicated to St Lawrence, was revealed. The floor area and truncated walls were unfortunately ravaged by pipes of a mid-20th century sewage system, services and associated sumps (Figure 2).

The surviving walls are to be preserved in situ beneath the proposed 'Events Centre', but cannot be presented visually owing to the tide levels, which regularly rise and fall in all the low-lying areas of Cork City. This situation leads me to one of the most informative aspects of the excavation, the evidence for reclamation.

In particular, the excavation of the basement area allowed the opportunity to excavate extensively at levels previously only glimpsed briefly at the bottom of deep cuttings in other archaeological excavations in the city. Early excavations in Cork City had stopped at the surface of a layer of grey estuarine clay, at that time believed to be a natural (pre-occupation) estuarine silt. The odd anomalous piece of worked wood or sherd of pottery had raised some doubts among the early excavators, myself included. The hand-excavation of sondages to one or two metres into the silt and clay barely assuaged our misgivings that surely these metres of almost sterile silt must be natural. How could these many thousands of cubic metres be otherwise, and all this below tide level too, sometimes even sea level, and yet there were nagging doubts about the odd deeply buried anomaly.

By the early 1990s archaeologists took courage (and mechanical excavators) to haul out masses of silt from below the earliest occupation levels and reach depths of two metres or even more below where evidence had been unearthed for manmade wooden platforms and reclamation fences. So, the indisputable conclusion was that the earliest settlement in Cork could not have been built on two marshy islands in the estuary of the River Lee but on a tidal estuary of many marshy islets, each artificially raised and retained by wooden fences linked by bridges and board-walks, with the intervening channels progressively filled as the settlement grew and land claim gradually expanded. By the time the first maps were made in the late 16th century, the walled city appeared as two islands and was described by Camden (1586, 1338) as 'of an oval form, enclos'd with Walls, and encompass'd with the Channel of the River, which also erodes it, and it is not accessible but by bridges; lying out in one direct street, that is continu'd by a bridge.'.

Owing to tidal flooding, any opportunity to investigate the lowest levels was always fleeting and fraught with logistical problems and risk.

Historically, basements were never a feature of Cork City and have not been included in recent city centre developments as the complexity and cost of construction exceeded the potential value. Then on the Brewery site in 2016, for the first time in Cork City centre, a basement area encased by contiguous piles and serviced by dewatering pumps created an environment where archaeologists and machinery were able to work at depths of c. 4m below modern ground level (Figure 3).

It was anything but dry, and heavy winter rain made the clays slippery and the mud often rapidly obscured the findings, but the excavation of a full transect from the street frontage to the city wall was a unique achievement. Evidence for the complexity of the reclamation process, beginning by the street frontage in c. AD 1070 and proceeding westwards in two or three phases until c. AD 1200, was one of the most worthwhile contributions of the excavation (Figure 4). The many other significant and impressive finds are too numerous to detail and beyond the scope of this article.

Apart from a few organised visits by students and staff of University College Cork and regulatory bodies, there was no opportunity for public visibility due to the confines of a construction site where strict health and safety protocols prevailed.

A visit to Cork by the Norwegian Ambassador to Ireland; Her Excellency Else Berit Eikeland in September 2017 occasioned the unveiling of some of the evidence of Viking Age finds from the dig (Figure 5).

Ms Eikeland urged us to exhibit some of the discoveries to the public. The Lord Mayor and staff of the Cork Public Museum were equally enthusiastic.

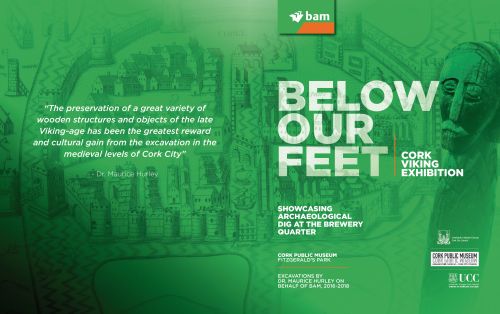

These proposals were draw up and presented to BAM who agreed to finance the exhibition, prepare a brochure and sponsor a presentation at the museum (Figure 6). While the exhibition was under preparation a presentation to the local archaeological society (Cork Historical and Archaeological Society) led to an unprecedented event, where large numbers seeking to attend a full to capacity lecture theatre had to be turned away; this followed from a newspaper interview where the findings were disclosed. University College Cork run a course in Museum Studies and agreed to offer their students the opportunity to work with myself and my excavation team to help prepare the exhibition and brochure. The students came from many different European countries as well as the United States. Cork City Council and The National Museum of Ireland also lent their support.

The opening of the exhibition was performed by the Lord Mayor of Cork and Ambassador Eikeland and the event was widely covered in local newspapers, local and national television, radio, news bulletins and international magazines. The exhibition was a great success and ran for over 18 months, and was viewed by an estimated 67,000 people.

Notwithstanding the enormous public knowledge dividend created by the exhibition, such initiatives can be risky in some respects. In the context of an Irish planning system that allows for third-party appeal, developers are understandably cautious of unbridled dissemination of information that has the potential to ignite public opinion. One aspect of this case study is salutary in regard to third-party appeals, whereby a planning application for a modified design of the Events Centre was appealed. The information and illustrations in the exhibition were used to augment an objection taken on the grounds of adverse impact on heritage. While I too share many of the objector's aspirations regarding the potential public benefit of heritage availability, it is unjustifiable to bundle everything that has gone wrong regarding Cork's heritage against a single development proposal which is poised to do so much for the most rundown and under-utilised part of the city. The development also carries the opportunity to work with the public to graphically illustrate the history and heritage of the site to a wide and varied audience. The objection was not sustained and permission was granted. Perhaps the real merits of this case lie in timely and factual dissemination of information to the public, avoiding ambiguous and emotive suggestion.

I would like to thank Mr Michael McDonagh, Chief Archaeologist, National Monuments Service Ireland, for offering me the opportunity to present this paper at the EAC 2020.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.