Cite this as: Cerbone, O., Garrisi, A., Giorgio, M., La Serra, C., Leonelli, V. and Manca di Mores, G. 2021 Italian Archaeology: heritage, protection and enhancement, Internet Archaeology 57. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.57.7

This article outlines the legislative provisions for the development of public archaeology in Italy. It will also consider to what extent such agreements have been successful in the 20 years since Valletta, and to what extent there is room for improvement.

In order to explain the current arrangements for archaeology in Italy, it is important to understand certain long-standing characteristics of Italian society, and some specific current circumstances in the country. It is well recognised that, within Europe, Italy is the country that first developed rules for the protection of its historical and artistic heritage: a direct consequence of an abundance that has few equals throughout the world. Our country has always been characterised by a landscape replete with ruins that was impossible to ignore.

This explains the early protection activity, beginning with large projects such as the Forma Italiae. This is an ambitious archaeological land register project, useful for historical research but also fundamental for the protection of the cultural heritage of the ancient world. The idea of an archaeological map of Italy was formulated in 1885, on the occasion of the first meeting of the Directorate of Antiquities and Fine Arts of the Ministry of Education. The legislative framework of pre-Republican Italy was expressed in terms of an educational mission. This ideological approach saw the 'Good' and 'Beautiful' as instruments for moral and cultural improvement. This approach was maintained in Republican Italy: the Gentile reform and Bottai law, which enshrined Benedetto Croce's spirit in article 9 of the Constitution, survived intact despite the fall of the Fascist regime, assuring authoritarian and paternalistic forms of social organisation in Italy during the post-war reconstruction.

Despite this early legislative activity, at the end of the last century our country suffered a sort of 'collapse'. First of all, the main legislative reference that gave the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities the task of protecting, conserving and enhancing the cultural heritage of our country is Legislative Decree number 42 (22 January 2004, Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape). But this code was already obsolete, since it did not include the Malta Convention, which was ratified by Italy only a decade later, with this delay causing severe consequences.

Morover, the Code did not contain the word 'archaeologist' anywhere and it was necessary to wait a further 10 years when law 110 (2014) included that substantial modification, with the introduction of article 9-bis which finally decreed our 'existence'. But it didn't end there, as law 110 provided for the establishment of specific Lists of Professionals of Cultural Heritage, which were established only five years later in May 2019, within Ministerial Decree 244.

During this long process of legislative recognition came an important point of reference, when the ANA (the National Archaeologists Association) qualified as a Category Association recognised by the MISE (Ministry of Economic Development) according to law 4/2013. Currently ANA is the largest association in our country, which brings together archaeologists operating in Italy, protecting the image and interests of our profession.

The origins of archaeology in Italy had a major antiquarian component, with a desire to show the aesthetic beauty of archaeological remains and in the beginning the relationship that developed within society was elitist. Over time, this exclusivity has continued to exist and the archaeological discipline has only been accessible to some areas of society. At the end of the last century the great building boom led to the discovery of extraordinary archaeological sites, but the need for civic developments was not well managed alongside the equal need for protection and enhancement of the newly discovered heritage.

This has led in recent decades to an intolerance towards the work of cultural heritage professionals, particularly archaeologists working in the field of public works. The cultural heritage that emerges in these circumstances is always seen as a problem and never a resource. As a matter of fact, the process that brought the public and individual regional communities to recognise heritage as a true common good was long-winded. A great boost to this process has certainly been given by international conventions: in 1972 the Paris Convention of UNESCO (World Heritage Convention), and the Council of Europe's 1992 Valletta Convention (Protection of the Archaeological Heritage) and 2005 Faro Convention (Value of Cultural Heritage for the Society). But the ratification of these conventions took place after lengthy delays in Italy, and today we are still waiting for the positive effects of the ratification. The Faro Convention has not yet been ratified.

In spite of this legislative delay, in Italy the concept of public archaeology has begun to be acknowledged, influenced by the international debate on the subject already underway since the 1970s (Bonacchi et al. 2019). Critical voices were already circulating in Europe towards an archaeology not very attentive to its public purpose and unwilling to involve local communities. Thanks to the Italian Congress of Public Archaeology, we also defined public archaeology as the disciplinary area that seeks and promotes the relationship that archaeology has established or can establish with civic society. The potential of this lies in the ability to create a strong connection between archaeological research and communities (local, regional or national). There are three sectors that fall within its sphere of interest: communication, economics and archaeological policies.

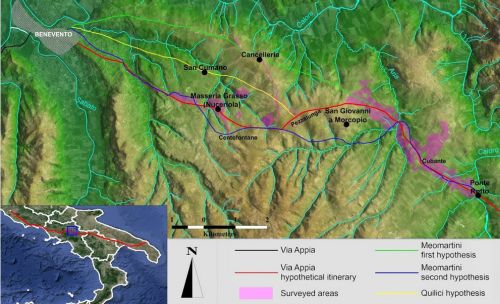

First of all comes communication. The Malta Convention itself, in articles 7, 8 and above all 9, makes reference to public opinion, and dwells upon the importance of disseminating information about archaeology to the wider society. A good example concerns the Ancient Appia Project, an investigation programme that has been taking place around the city of Benevento since 2011. The work is done by the University of Salerno (DiSPac) as part of the Ancient Appia Landscapes project, with the aim of recognising the environmental context, socio-economic and productive activities that contributed to the settlement and population dynamics along the Appian Way (Figure 1). The project aims to support and enrich knowledge of these contexts, not only the relationship between the environment and the community, but also cultural components such as use of resources for development and self-preservation of communities. This is achieved through a series of design ideas and agreement protocols, which can also be used to encourage tourism in this rural area.

The Appia Project demonstrates how communicating and making the results of research available democratically can help designers, local authorities and inhabitants understand the archaeology and evidence of the past as the drivers of progress, which can then be used to inform the current vision of the area. In accordance with what was defined in 2008 by the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape, we want to enhance the importance of the cultural perception of the landscape in order to weave embedded identity ties with the places of modern life. These two concepts are necessary in a world now projected towards globalisation, while we must also maintain an awareness that protection must go beyond conservation alone.

In Italy, unfortunately, we note a considerable difficulty in transforming scientific excellence into opportunities for socio-economic development. However, some projects do succeed, an example of which is the small civic museum of Sorso, Biddas, in Sardinia. It is a regional thematic museum focusing on abandoned medieval villages (https://www.facebook.com/MuseoBiddasunofficial/). In this museum the distance between the public and the artefact as an object of communication has been ideologically rejected and energy was invested in communication, as part of the desire to create a museum that was actually (not just in the publicity) a museum for all. It was this new concept of communicating archaeology that resulted in the museum winning the prestigious Riccardo Francovich Prize, awarded by SAMI, the Italian Medieval Archaeologists Society in 2013. The communication is innovative; it does not take a didactic or scholastic approach, but instead it focuses on emotional learning by the visitor with the creation of complex learning environments, enabling understanding at a sensory level using dynamic sounds and images. It involves participatory storytelling, with visitors to Biddas finding themselves immersed in the complexity of the context and looking beyond a few fragmented finds. Taking this perspective, the sense of the traditional museum collection is lost and the finds become protagonists (Figure 2). They are replaced by virtual artefacts or copies that visitors can examine or touch without the distance created by the display case.

A similar experience also occurred with an archaeological park, Archeodromo in Poggibonsi, Tuscany, where some researchers and archaeologists from the University of Siena are reviving a medieval village (Figure 3). Public archaeology, in short, finally begins to assert itself also in our country, albeit timidly and late compared to the rest of Europe. Archaeological research can be transformed from being seen as a public cost to a provider of new economic, social and cultural development. We must get away from the idea that cultural entities are merely a cost and understand that they encourage balanced growth, in which local communities, history and landscape, natural and historical, are incorporated together to form a resource for the benefit of all inhabitants.

However, we must not move towards an inverse process that considers cultural heritage as 'homegrown oil'. This is a distorted and unacceptable idea because it means considering it only from an economic and potentially profitable perspective. Even this comparison does not work, as oil is a finite resource both in its extraction and in its monetisation, while the consumption of cultural goods is a self-sustainable resource that increases the value of the good itself. Once 'extracted', the cultural property becomes a generator of potentially infinite and renewable economic resource, as long as it is protected, valued and properly used. The risk, however, is that the economic value predominates above the cultural value and, as a consequence, tends to distort dynamics in the working world of the professions engaged in the different areas of cultural heritage. All this would inevitably lead to an impoverishment of the professional offer in support of the cultural heritage, thus generating a paradoxical contrast with the very principles of the Faro Convention, which instead are appropriate to pursue with far-sighted policies and strategies.

Furthermore, for Italy it is also necessary to analyse the phenomenon of demonisation of the private stakeholder, which derives from the fact that the state operators of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities (MIBACT) are the only ones authorised to contract and manage archaeology. There has always been a strong emphasis on private property rights in Italy. We see it in the limitations of the Code of Cultural Heritage, which limited the Superintendent's powers in precautionary and preventive measures to public works only (article 28 paragraph 4). The Public Procurement Code also makes the same limitation and only recent legislation (Law 106/2011) imposes archaeological control on the public works sector, and includes so-called 'special sectors', which relate to particular projects financed by private individuals but with a major impact on the public. This is a further failure to implement the Malta Convention, which our country could easily overcome with a simple modification of the aforementioned article 28: the addition of the word 'private', to become 'the Superintendent has preventive powers over public and private works'. This omission influences the approach to archaeological heritage protection and management in a number of ways. The real problem in Italy is that the State is the only body to manage the cultural heritage, which can be counterproductive both in practice and from an economic point of view as it comes with the risk of a deregulated private market. It falls to the public sector to take political responsibility for including the private sector in the management of cultural heritage in ways that allow the private sector to make profit while also guaranteeing protection. We have seen this phenomenon with the Biddas Museum mentioned above, where the concept of the traditional Italian museum has been renewed. As has been shown, many traditional museums are not inclusive and the majority of visitors are not fully satisfied or involved in the visitor experience. The museum, as the house of the Muses, should reflect our society, which is of course very varied, consisting of visitors who can decode the complex professional languages that accompany exhibitions, as well as a large element of the public that needs mediators to help with the language and presentation. Children in particular need encouragement (for example the experience of 'La città di Ruggero', Mileto) (Figure 4).

The experience of a museum that does not start from the State but from private business has shown how the creation of inclusive museums can mean creating living museums, interconnected to the region and to the current communities that use it, live it and actively experience it, creating public benefit and improving their quality of life.

So: what can we actually do for the future? Transforming opinions about archaeology from a public cost to a balanced socio-economic-cultural development potential is a real challenge. Clearly the initial capital investment is a major issue, and there are also significant costs associated with ongoing conservation and maintenance on sites and in museums. Cultural heritage can become a lever for healthy and balanced economic development, but in order to achieve this, it needs wide-ranging policies and also suitable reforms, which make the most of the regulatory framework and the Malta and Faro Conventions. This will place communities, regions and cultural heritage as the priority at the centre, studied, investigated and protected by responsible professionals and hence enjoyed by all possible stakeholders. The regulatory aspect is necessary to guarantee the protection and usability of our heritage, to preserve our identity that derives from it, and then to produce income and employment in a sustainable and shared balance of priorities.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.