Cite this as: Oksanen, E. and Wessman, A. 2025 New horizons in understanding Finnish Iron Age material culture through metal-detected finds, Internet Archaeology 68. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.68.4

Recreational metal detecting is a complex and varied topic that has strong implications for our cultural heritage. In Europe, legislation varies: while some countries have placed heavy legal restrictions on metal detecting that effectively make it illegal as a recreational activity, others have adopted a more liberal stance and operate national reporting schemes in order to publish finds records in online databases (Deckers et al. 2016, Lewis et al. in press, Wessman et al. 2023). Metal detecting has therefore remained at times a controversial subject, which nevertheless touches upon several current themes in European archaeological heritage management including public participation in heritage, the protection of vulnerable archaeology, the potential for new scientific breakthroughs, the digitisation of cultural heritage, and Open Cultural Heritage.

In this article we explore the emergence of recreational metal detecting in Finland and its impact on our archaeological knowledge of the past, with a specific case study on Finnish Late Iron Age (AD 800-1200/1300) material culture. Our aim is to show that Finnish metal-detected finds have high untapped research value, especially — though by no means exclusively — as archaeological 'big data'. Traditionally, the majority of archaeological evidence for the Finnish Iron Age derives from cemetery excavations, and this remains the case today (e.g. Raninen and Wessman 2015). Yet, the thousands of metal-work objects that have been recovered over the past decade offer new and largely unexploited sources of information through which we can learn about Iron Age culture and society.

The principal research dataset investigated here comprises 6123 database records created by the FHA 2015-2023 on retrieved public finds, supplemented by 2296 public finds retrieved 2000-2015 and recorded into PDF catalogues 1. The method of discovery for pre-2014 finds is not consistently recorded, but c. 88 per cent of all finds from 2015 onwards were made by metal detecting. As has been explored in other European contexts (e.g. in the UK see Bevan 2012; Cooper and Green 2017; Oksanen and Lewis 2020; 2023; and the Netherlands see Kars and Heeren 2018), such a body of evidence is well suited for large-scale Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and other computational analyses. Despite a few recent initiatives (e.g. Ehrnsten 2019; Hänninen 2020; Wessman and Oksanen 2022; Leppänen 2022; Rantala et al. 2022) these have, however, remained an under-used approach in Finnish public finds and Iron Age archaeology. Most of the archaeological research on metal-detected small finds in Finland has been conducted on individual discoveries (e.g. Immonen 2012a; 2012b; 2013; 2016; Wessman 2016; Rohiola 2019), and quantitative approaches have been less explored. There is therefore a considerable potential for both advancing knowledge of the Finnish past, and for advancing archaeology as a scientific practice in Finland, around the topic of metal detecting.

Engagement with the material, however, requires an understanding of the complex processes that have produced it. The reservoir of Finnish national archaeological cultural heritage data, as curated by the Finnish Heritage Agency (FHA), is making strides towards meeting modern FAIR data standards (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable; see Wilkinson et al. 2016) but much work remains to be done (Oksanen et al. 2024, 4-5; Rohiola and Kuitunen 2022; Roiha and Holopainen 2023). The available public finds datasets, as is often the case with cultural heritage data archives, are themselves an expression of various cultural, social and institutional phenomena (cf. Gosden et al. 2021; Newman 2011). In this article, we therefore also explore the reuse potential of the Finnish public finds data, highlighting how recovery and reporting biases, as well as collection management policies, have powerfully influenced its formation. Building upon theoretical and methodological advances made in the last decade, we showcase a mixed-method combination of qualitative understandings of past archaeological phenomena and modern processes, with the novel interpretative perspectives that geographically and temporally large-scale quantitative analysis affords, as a case study for studying European metal-detected public finds data on a national scale.

Metal detecting is generally permitted in Finland, although it is not specifically mentioned in the Antiquities Act of 1963 (recognised as outdated and currently under reassessment). It is nevertheless forbidden by law to excavate, cover, alter, damage or remove archaeology from the ground at known ancient monuments and other archaeological sites (Antiquities Act 295/63 1 §), and these prohibitions also restrict activity in certain other vulnerable landscapes (e.g. the Nature Conservation Act 1096/1996). Artefacts recovered by legal and responsible metal detecting are understood to be either stray finds, or part of a previously unlisted archaeological site; in the latter case the site can subsequently be brought under the protection of the law and safeguarded against other common sources of potential damage such as the construction or forestry industries (Maaranen 2020).

Archaeological finds over 100 years of age must be reported to the FHA, a process that has been greatly facilitated since the 2019 launch of the electronic reporting tool Ilppari. If deemed of sufficient archaeological importance or interest, the FHA transfers2 the recovered objects to the national collections (FHA 2016). It is important to note that these are the only finds that will be examined in greater detail and entered into an electronic archaeological Luettelointisovellus (since 2023 Apuri) database. In practice all reported medieval and prehistoric objects, but only a small percentage of younger finds, are transferred and recorded. Other objects remain the property of the finder, with only the finds report as a record (with the special exception of coins reported 2013-2023, see below section 2.1).

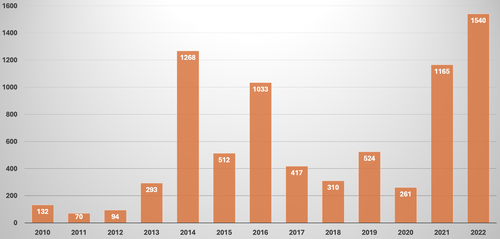

Recreational metal detecting became more popular in Finland during the early to mid-2010s (Immonen and Kinnunen 2016, 165-8). In the 2000s, an average of 40 to 50 post-Stone Age objects per annum recovered by members of the public — whether by metal detecting, fieldwalking, agricultural activities, as construction site finds, or by other means — were retrieved (source: Muinaiskalupäiväkirja archaeological object register). As Figure 1 shows, these numbers subsequently grew by more than an order of magnitude (Oksanen et al. 2024; Wessman et al. 2019). This burdened the heritage management, which lacked the resources to respond to the initial upsurge in demand for processing, recording, conserving and archiving newly discovered finds. The lag between reporting and recording finds is currently roughly three years, although some finds (for example if deemed particularly significant, or selected for exhibitions) may be recorded much more quickly.

In response to these challenges, stakeholders in the Finnish archaeological and culture heritage field have developed and rolled out various initiatives. These involve new digital infrastructure including the development of the reporting service Ilppari, and in 2023 the launch of the new internal data management tool Apuri to replace the old Luettelointisovellus archaeological database (Oksanen et al. 2024, 4-5); a guide to responsible metal detecting as an educational resource (FHA 2015; 2016); hiring new staff to speed up finds recording; and scientific research including the projects SuALT: Suomen arkeologisten löytöjen avoin linkitetty tietokanta (Finnish Archaeological Finds Recording Linked Open Database, 2017-2021) and DigiNUMA: Digital Solutions for European Numismatic Heritage (2022-2024).

These two projects, as collaborations between the Helsinki and Aalto universities, the FHA and the National Museum of Finland, were variously engaged in archaeological, Digital Humanities, ethnographic, collections management, numismatic and Computer Sciences research on the metal detecting phenomena and the new data thus generated. Notably, they have launched the FindSampo and CoinSampo Open Cultural Heritage data services (Hyvönen et al. 2021; Rantala et al. 2022; Rantala et al. 2024; Oksanen et al. 2022; 2024; Thomas et al. 2022; Wessman et al. 2019). The former opens data on public finds retrieved for the national collections, while the latter opens data on reported numismatic objects regardless of whether they were retrieved. Both were developed as scientific data service demonstrators and proof-of-concept models, however, and owing to resource constraints at the time of writing neither has been taken over by the FHA for long-term development, maintenance, and updating beyond the initial data dumps at launch. Further development is, however, envisaged in the context of the newly launched Arkeologia 2.0 consortium for modernising the Finnish digital cultural heritage infrastructure.

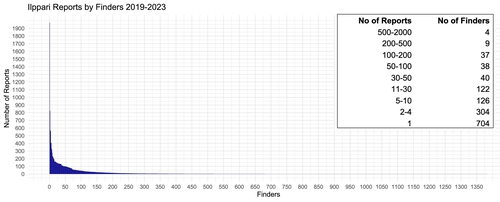

The number of active metal detectorists in Finland is difficult to pin down, though an assessment of three surveys published 2014-2019 estimated it to be between roughly 800 and 900 individuals (Immonen and Kinnunen 2016, 168; 2020). More recently, the online archaeological reporting service Ilppari contains public finds (not all metal-detected) reports made through 1348 registered accounts between February 2019 and May 2023 (Esineilppari database dump obtained 6 May 2023). Such numbers require interpretation, however, as there is considerable variety among finders. While for many detectorists metal detecting is merely an occasional recreational hobby, for others it is a serious leisure activity into which a great deal of time is invested. Many become highly skilled in the use of a detector, as well as in archaeological research and object identification (Stebbins 2007, elaborated in Ferguson 2013; in the Finnish context see also Wessman et al. 2019; Immonen and Kinnunen 2020; Wessman 2023). The detectorist community is therefore not a homogeneous group. The vast majority of Finnish detectorists report only a few finds per annum to the FHA but, as in other European countries, there are detectorists and clubs (identified as so-called 'super-users': Lykkegård-Maesand and Dobat 2022) that have reported hundreds of finds per annum (Fig. 2). This outsized impact of a small groups of 'super-users' was already present since the earliest years of the Finnish metal detecting phenomenon (Rohiola 2015, 21)

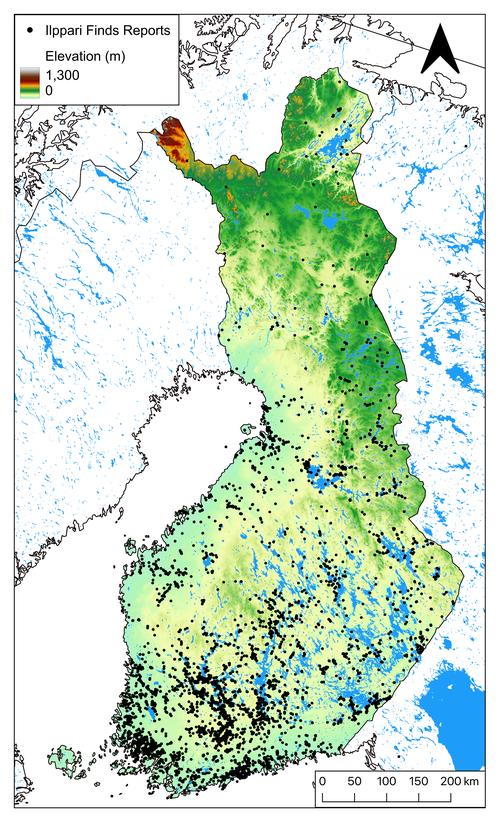

This heterogeneity introduces regional biases in the data. Two south-western regions stand out in the number of finds reported and recorded: Southwest Finland by the coast and Häme further inland (see Figs 3 and 6). In 2014-2016 the detecting club 'Kanta-Hämeen Menneisyyden Etsijät' (KHME), held a significant role in kicking off the metal detecting boom in Finland (Rohiola 2015; Hänninen 2020). From 2016 the club 'Varsinais-Suomen Metallinetsijät' (VaMe) in the south-west rose to become probably the most active detecting club in the country (Leppänen 2022, 33-34). These clubs differ from each other. KHME is a closed club with only six individuals (Wessman 2023) and its activity has declined in the recent years, while VaMe has a looser approach to membership with new members joining the group at all times, thus continually increasing the number of finds reported. Geographical bias in find densities is further enhanced by modern and historical demography as the Finnish population is concentrated in the south (Statistics Finland 2023), and by topography as most cultivated land, preferred by detectorists, is also in the south (cf. also Fredriksen 2023 for comparable examples elsewhere).

A wide variety of different metalwork objects are recovered through metal detecting, from household items to weapons and animal harness objects. Yet, like elsewhere (Oksanen and Lewis 2020, 3-4; Fredriksen 2023, 225), the largest categories of metal-detected small finds recorded in Finland comprise coins and dress ornaments (see also Hänninen 2020, 73; Leppänen 2022, 62, for regional deep-dives in Häme and Southwest Finland). There are good reasons for this that can be linked to the sampling biases that influence the formation of the metal-detected archaeological record, as has been explored by Katherine Robbins in her groundbreaking study of the English and Welsh material (Robbins 2012; 2013; 2014). Robbins formulated a seven-stage framework (deposition, preservation, survival, exposure, recovery, reporting and recording) for exploring the filters and biases that govern the composition of metal-detected finds databases; from the perspective of cultural heritage management the final three are of particular relevance. In addition to being findable with a metal detector in the first place (i.e. a metal object of sufficient size, buried not too deep in an environment where detecting is possible), the object has to be recognisable as possessing archaeological value for it to be reported, and finally it must be deemed of sufficient archaeological importance or interest to be recorded. This means that the finds data that arrives to us is contingent on a number of processes that must be appreciated at reuse. We discuss Finnish particularities through two case examples.

Coins are a good example of an object type with a mixture of both positive and negative biases in Finland. While some detectorists ignore or set their machines not to pick up on ferrous materials owing to the prevalence of scrap iron, coins are typically made of noble or at least non-ferrous materials. Coins and other numismatic objects are among the most common find types (c. 13 per cent in the Finnish public finds data), are unusually easily recognisable, and many can be precisely dated even by untrained eyes. As numismatic objects they are also of special interest, and many detectorists collect the coins they are not obliged to hand in to the authorities (e.g. Siltainsuu and Wessman 2014, 37; Moilanen 2023). Long-standing scholarship has developed detailed numismatic typologies, which has enhanced general interest and increased the body of scientific knowledge available to hobbyists and heritage professionals, undoubtedly encouraging recovery and reporting (Talvio 2003; Oravisjärvi 2015; 2021).

Urbanisation and a widespread monetised economy arrived relatively late to Finland, only at the dawn of the Early Modern Period (from AD 1560: Ehrnsten 2019). Of particular interest to both numismatists and detectorists have been the Viking Age (AD 800-1050) hoards and single finds recovered by detecting (Fig. 5e: Ehrnsten 2015; Talvio 2003, see also CoinSampo below). As with all finds, Early Modern and modern coins are taken into the collections only selectively. However, a separate initiative for recording the core information (e.g. denomination, year, issuer, mint and findspot) of all historical coins reported was carried out at the Numismatic Collections of the National Museum of Finland between 2013 and 2023 (Oksanen et al. 2022; 2024). These data can be accessed via the CoinSampo numismatic cultural heritage portal (Rantala et al. 2024). A comparison between this numismatic dataset and the overall archaeological collections data shows that since the onset of the metal detecting boom only c. 11 per cent of reported coin finds have been added to the collections and therefore fully recorded in the national collections database, highlighting the bias in the character of metal-detected finds data that is collected.

There might be several reasons for this. First, during the early years of the Finnish detecting boom, detectorists were given conflicting advice by professionals on what and what not to report, depending on to whom they were talking and in which part of the country they were based (Wessman 2020). Newcomers to the hobby perhaps over-reported everything, as was indeed required by the letter of the law. Written guidelines for detectorists were not published until 2015 (with an English version in 2016: FHA 2016). Furthermore, from the perspective of the detectorist community there may have been a misunderstanding that 'reporting' always meant 'handing in' a find, which it does not. And to make things even more complicated, some detectorists were reporting and handing in their finds to local museums instead of to the FHA, where the finds might wait for years before being transferred over (Ehrnsten 2015).

Second, until February 2019 all finds were reported to the FHA by email and an attached Word.doc form. This was complicated and time consuming both to produce (for the finder) and to process (for the FHA), and several detectorists reported only the finds they knew (or assumed) were of interest to the Agency. After all, detectorists that had been detecting for a long time were aware that the FHA was not interested equally in all time periods, and would not take all reported finds into the national collections (Ehrnsten 2015, 47; Thomas et al. 2022, 170-71).

This highlights the FHA's collection's focused recording bias, and the fact that a proper (i.e. meeting archaeological standards) record is created only of retrieved non-numismatic finds. Yet, as the CoinSampo has demonstrated, a scientifically important body of data (as 'big data') is created by even a basic record of all archaeological reported finds, even if the reported objects themselves (such as well-known Early Modern coins) are not in themselves equally archaeologically valuable as individual instances of the wider material culture. It is unfortunate that a considerable amount of potentially ground-breaking information is lost in Finland owing to restrictions in recording policy, although this is a matter of triaging the deployment of limited resources rather than of intent.

Late Iron Age (AD 800-1200/1300) female dress ornaments exemplify a somewhat different set of historical and modern processes that contribute to their high numbers in the finds data. Material culture became more abundant during this period. The female dress became much heavier, with more copper-alloy ornaments (e.g. pendants, keys, bells, and ear spoons) hanging from chains that ran between dress brooches (Raninen and Wessman 2015, 296; Gustin and Wessman 2021, 63). This richer dress style could have led to a higher rate of casual losses of objects that may survive in the soil, later found and recognised by detectorists.

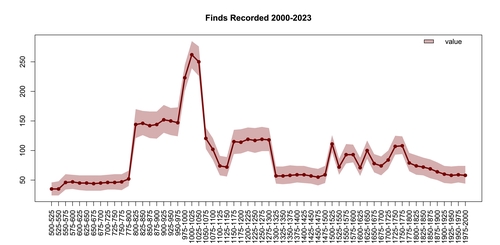

Figures 4-5 show diachronic perspectives on how the combination of sampling biases from deposition to recording has come together to form the Finnish finds data. We use aoristic analysis, a Monte Carlo simulation-assisted probability modelling method that is particularly well suited for representing temporally uncertain archaeological data (Crema 2012; Orton et al. 2017; and see Oksanen and Lewis 2020; 2023, for its use in public finds data). The graphs display a temporal distribution of recorded public finds from the Late Iron Age to the modern day, also divided into chronological slices by year of recording: pre-metal-detecting boom (2000-2013), onset of the hobby (2014-2016) and the latest recorded finds (2017-2023). Compared are also c. 3000 recovered dress ornaments, and c. 1000 coins or hacksilver (bullion) objects.

As Figure 5 shows, before systematic metal detecting took off in Finland around 2013, finds were being reported more or less equally from all time periods. The slight bump around the twelfth and thirteenth centuries is interesting but cannot be considered significant based on only this data, as a straight horizontal line (indicating an even distribution across all time periods) would also fit inside the 95 percent confidence envelope. But right from the onset of the boom in the early 2010s the Late Iron Age emerged as being of special interest. Ethnographic interview material shows that Finnish detectorists are often intrigued by the Late Iron Age, and the Viking Age in particular, which means that they give special attention to searching for artefacts from these periods (Wessman 2023, 200; Wessman and Thomas 2024). Most people across Europe are aware of the Viking Age owing to its representations in popular history and culture, and in north European countries there are also nationalistic or political connotations to the period (see e.g. Rosenström and Žiačková 2022). The very noticeable finds spike during the Viking Age is formed of several hundred coins (both European and Arabic) dated between 800 and 1050, but also large numbers of dress accessories, including round (114 finds), equal-armed (76) and penannular (31) brooches, and also many other types such as rings, neck rings, pendants and decorative mounts.

Experienced avocational detectorists know where to look for Late Iron Age finds, focusing in regions well known from previous archaeological work (see Section 3.1 on distribution of known Iron Age sites). During the Late Iron Age, the mortuary practice was cremation in low stone settings (polttokenttäkalmisto or 'cremation cemeteries under level ground'), which may not be easily visible on the ground and are vulnerable to ploughing and building activities (see Wessman 2010, 21-23, 36). A significant number of recorded (thus, pre-modern) non-numismatic ploughsoil detector finds in southern Finland are assumed to be from destroyed cremation cemeteries. These make appealing targets for detecting. Detecting clubs often have 'insider' knowledge of the history, archaeology and geography of their local region and also possess good contacts with landowners (Wessman 2023, 202-3), all of which can be deployed as a tremendous resource in their search for objects of the past. Given that ploughsoil finds are slowly and continually being destroyed by the action of machinery and by the chemicals used in modern agriculture (Haldenby and Richards 2010, 1160; Robbins 2014, 29; Dobat 2016, 52; Henriksen 2016, 75-6), we argue that responsible and rules-adherent detecting in this context is in fact saving many artefacts from being destroyed further,3 despite the burden of, for example, conservation costs this may include.

Following the general trends of the public finds data, we focus our discussion on the Finnish Late Iron Age. During this period the agrarian settlement was mainly concentrated along the coasts, rivers and lakes of the southern half of Finland: in the south-west on the Åland islands and mainland regions of South Ostrobothnia, Satakunta, Southwest Finland and Häme, and in eastern Finland along the extensive network of lakes and rivers in Savo and Karelia. People in these core demographic areas practised a mixture of livelihoods consisting of farming, animal husbandry, fishing and hunting (Raninen and Wessman 2015; Raninen 2020). Most Finnish archaeological research has historically concentrated on these regions. Although they were geographically connected, towards the end of the Iron Age we can distinguish culturally separate regions in the east and the west. We will first map the geographic distribution pattern of (retrieved and recorded) metal-detected finds, and then discuss how these data are transforming understanding of Late Iron Age archaeology.

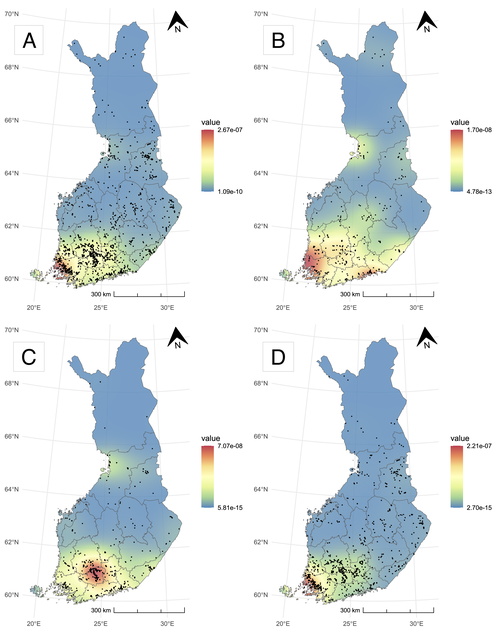

Figure 6a is a distribution map of all the 8419 public finds reported and recorded between 2000 and 2023 in our dataset, underlain by a kernel density surface 'heat map' (O'Sullivan and Unwin 2010) that helpfully visualises the relative densities of regional finds concentrations. New finds can and will change the picture, but the overall contours are already illustrative of major patterns in material culture recovery. There is a clear geographical bias in findspot concentrations in Häme and the south-western coastal regions owing to 'super-user' detectorists in the area. If we look at the distribution of finds reported by chronological slices, as defined above, the impact of regional metal detecting clubs becomes even clearer. The map of finds made before 2014 (Fig. 6b) is somewhat reflective of modern population densities and of our understanding of the distribution of permanently settled communities during the Late Iron Age. A significant portion, perhaps most, will have been chance finds made while walking in forests, fields or at shorelines, or during various construction projects.

Thereafter the situation changed quickly. The impact of KHME is clearly seen in finds recorded 2014-2016 (Fig. 6c), with the large concentration of finds in central Häme. As the 2017-2023 map (Fig. 6d) shows, activity in this region has continued thereafter (note the distribution of findspots), but in relative terms most finds were made near the south-western coast (note the underlying kernel density surface). It is not, of course, only the number of finds, but what new information small numbers or even individual finds can reveal about an area that is of importance in advancing archaeological knowledge.

Many Finnish avocational metal detectorists invest considerable time to develop skills and knowledge in the use of the GIS resources relating to archaeological and geographical data (e.g. Siltainsuu and Wessman 2014, 36-38). Key databases are made freely available by Finnish public institutions, including site locations from the FHA's Register of Ancient Monuments database. One avocational detectorist, who collaborated with the authors during fieldwork in 2022, estimated that they spent more time in front of a computer than in a field with a metal detector. This has been noted elsewhere among Finnish detectorists (e.g. Wessman 2023). Therefore, while responsible avocational detectorists will avoid archaeologically protected areas, they may naturally target areas that possess an elevated chance of new archaeological discovery based on their research and understanding of the local cultural historical landscapes. Once new finds and observations of surface monuments have been reported, professional archaeologists can be dispatched to verify the presence of an archaeological site. As will be discussed next, this self-driven grassroots citizen science activity accounts for the significant numbers of new (especially Iron Age) sites that have been discovered and consequently brought under protection in Finland in recent years.

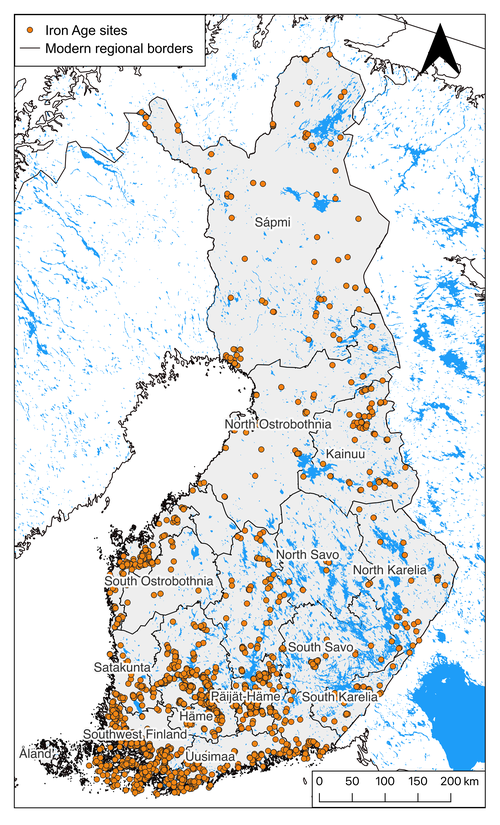

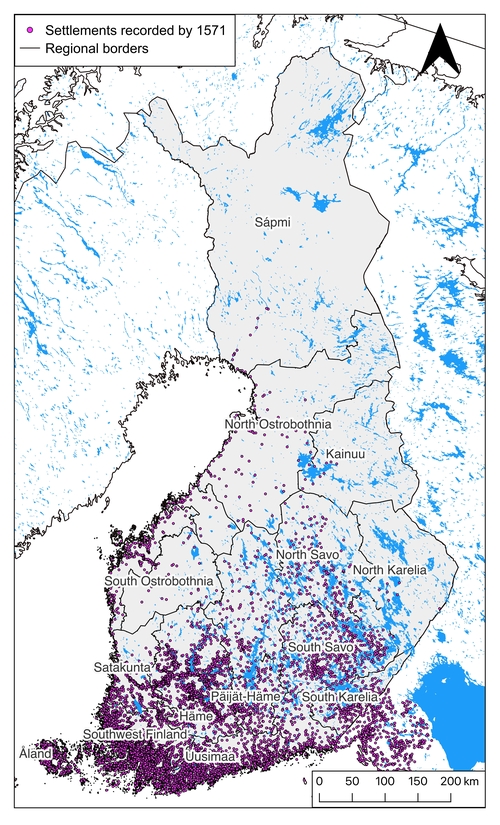

A fuller picture of prehistoric settlement patterns is still emerging, but a broad model reflecting our current understanding of the distribution for Late Iron Age and medieval settlement patterns is presented in Fig. 7a-b. These maps show the site distribution of Iron Age settlement and burial sites in mainland Finland (Åland has a separate archaeological register) recorded in the FHA's Register of Ancient Monuments database, supplemented and compared with known settlement locations by the end of the Middle Ages, as collected and collated by National Archives of Finland (Kansallisarkisto 2023). In the following sections we will summarise the character of Late Iron Age settlement landscapes in Finland divided into three main geographical regions, discussing these regions in the light of new information created by archaeological metal detecting.

The Åland Islands, in south-western Finland's archipelago, is an archaeologically distinct area. Due to its geographical closeness to Sweden, it was culturally more or less homogeneous with eastern Sweden during the Late Iron Age. This can be seen in both the burial practice, with Scandinavian mounds, and the material culture (Ahola et al. 2014). Åland is an autonomous region and, unlike in the rest of Finland, recreational metal detecting is largely restricted there. On the Finnish mainland, the material culture was different. On the south-western and western coast, in the areas of South Ostrobothnia, Southwest Finland, Satakunta and Häme, settlements were concentrated along river valleys and smaller lakes. These areas were well suited for permanent agriculture, as well as for fishing, with the water routes enabling contacts near and far. The burial practices were varied, consisting both of cremation cemeteries and of inhumation (Wessman 2010; Moilanen 2021).

As noted, the popularity of metal detecting first surged in the south-west of Finland, fed by the relatively large number of known sites and the already large body of regional archaeological knowledge. This has led to a form of virtuous cycle, with new sites being identified and brought under protection (Hänninen 2020; Leppänen 2022). It has also not been without its problems. This was especially so in the early years of the boom, when some still-inexperienced hobbyists carried out detecting in a non-responsible manner and damaged archaeological sites. A recent study by the FHA, however, has shown the positive impact of educational outreach, with instances of assessed damage decreasing over the years (Maaranen 2020; see also Hänninen 2020, 69-70 and Leppänen 2022, 42, on the improving reporting standards). In other nearby regions, such as in Uusimaa on the southern coast, metal detectorists have found new evidence of settlements. Despite being scarcer in numbers than in Southwest Finland and Häme, this shows that habitation continued there throughout the entire Iron Age (Wessman 2016; Wessman 2022). This had not been proven before metal detecting began there.

The northern parts of Finland, including North Ostrobothnia, Kainuu and Sápmi, were inhabited by different mobile groups including the Sámi (Halinen 2022; Hakamäki 2018). The areas were also utilised by the agrarian communities living on the western and southern coasts for economical purposes such as fur hunting or trade (Raninen and Wessman 2015, 320-23 with references; Kuusela et al. 2020). Copper-alloy objects found in Sápmi, which originated in the agricultural areas of southern Finland and the eastern parts of Karelia, are nowadays mostly associated with burials and offering sites of the Sámi (Schanche 2000; Hansen and Olsen 2004). Metal objects from the boreal areas are scarce, often consisting of fragmented copper-alloy sheets, which are difficult to interpret (see e.g. Hakamäki 2018). Stray finds deriving from this area were traditionally explained away as casual losses from hunting expeditions by the agrarian communities from the south (Nurmi et al. 2020; Raninen and Wessman 2015, 261-62), but this view has changed.

Figure 7b shows how the Sámi population was still not taxed in AD 1571. The only historic settlements recorded are the hubs connected to trade, suggesting the presence of a Swedish trade elite (Birkarls) along the rivers of the Bothnian Bay (Kuusela et al. 2016; Nurmi et al. 2020).

Recreational metal detecting, however, has now produced archaeological finds through a broad geographical region, from North Ostrobothnia to Kainuu and further north. Archaeological excavations of these metal-detected stray finds have proven that many of the find sites are indeed settlement sites or cemeteries (Kuusela et al. 2016; Hakamäki 2018). This indicates previously unknown permanent settlement patterns in inland areas and along important water routes, often in well-organised hubs with far-reaching trade contacts (Kuusela 2014; Nurmi et al. 2020). These northern trade routes were important for transporting both fish, fowl, fur and other animal products to the European continent, and it has left evidence in the forms of imported artefacts (Kuusela et al. 2020, 150). New burial evidence and traces from social hubs also indicates permanent settlement around the Bothnian Bay in North Ostrobothnia (Hakamäki 2018; Kuusela et al. 2020; Wessman and Oksanen 2022). These new findings are transforming our understanding of the communities living in northern Finland.

The eastern and central parts of Finland consist of large lake systems (Lake Saimaa, Päijänne, Pielinen and Kallavesi) with extensive waterways. Savo and Karelia have traditionally been interpreted as settled via inland water routes by farmers from the western coast (Raninen and Wessman 2015, 265). In the area of Mikkeli in South Savo there was a cluster of permanent settlements from the 6th century AD onwards, and the north-western shores of Lake Ladoga in Karelia had been settled by the 8th century. These areas most likely had direct contacts with the eastern trade routes during the Viking Age, and even before, influencing local material culture (Uino 1997; Mikkola 2009; Mikkola and Talvio 2000; Raninen 2020). Occupations consisted of permanent farming in the core areas (Mikkeli and on the north-western shores of Ladoga), supported by hunting, trapping and fishing. Outside the core areas subsistence was probably more dependent on slash-and-burn cultivation, in addition to hunting and fishing. There have been several Viking Age finds recovered from these outland areas, but we still know very little about the settlement patterns suggested in Figure 7a-b (Jääskeläinen 2019). Hence, while there is an enormous amount of potential in new finds data to offer more evidence about the Late Iron Age in this vast inland area, metal detecting activity to date appears to be relatively low.

Here too, however, responsible metal detecting has demonstrably already advanced our knowledge of the region's archaeological past. In the Päijät-Häme region of south-central Finland 171 new Iron Age sites were recorded in the Register of Ancient Monuments between 2020 and 2023, representing a 35 per cent increase in known sites in just four years. The majority of these were brought to archaeologists' attention by metal-detected finds. A recent study (Roiha and Holopainen 2023), which performed a deep analysis of the region's available data sources in the Register, confirmed that settlement patterns in Päijät-Häme were archaeologically more complex than had been classically assumed. As more information is generated, it is likely that similar insights will be generated concerning other nearby regions. A notable example is an early Iron Age (410-355 cal BC) cairn site at Puijonsarvennenä near the city of Kuopio in the region of North Savo. The site was first discovered by a detectorist in 2019 and subsequently professionally excavated with fieldwork assistance from the original finder and another detectorist. At that time it was the only Iron Age burial site to have been excavated in North Savo, underlining the importance of these findings. The archaeologists involved noted that the structure was visually undetectable in its forested landscape context, and concluded it is likely there are other similar sites in danger of being destroyed by local construction and forestry industries (Knuutinen et al. 2022, 22). We hope that responsible metal detecting and other public finds will therefore continue to have a significant impact on understanding settlement and demographic patterns, as well as a positive impact on protecting vulnerable archaeology.

Despite its evident potential, the various regional and data management biases in the Finnish metal-detected finds data can make it a challenging resource to utilise. Finds, as individual examples of object types, sites or deposition practices, are nevertheless advancing our understandings of the past (e.g. Wessman 2016), and we furthermore argue it is possible to deduce significant large-scale spatial processes and patterns within wider material cultures from the data. The sample is by now sufficiently large and diverse that results may be obtained by examining spatial distribution breakdowns of object types (see recently Raninen 2024), or comparing different finds type distributions with each other and with other spatial features. Moreover, the data visualisation, statistical and analytical techniques deployed do not need a great deal of specialist knowledge other than a fairly basic experience with free Open Source GIS or coding software, making these data widely accessible for research use among both the professional and the non-professional (citizen science) communities. The barrier for entry for all potential user groups is further lowered by the FindSampo and CoinSampo portals, which contain inbuilt data visualisation tools for mapping and creating various statistical breakdowns (Hyvönen et al. 2021; Rantala et al. 2022; Oksanen et al. 2024; Rantala et al. 2024).

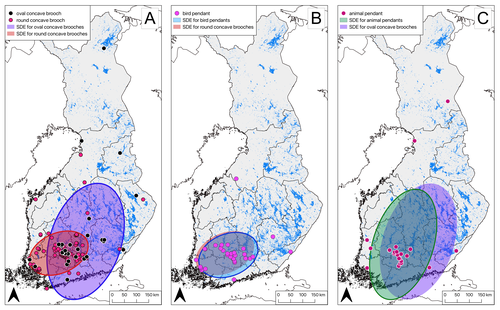

We have picked two Iron Age female brooch types as a case study with which to examine the new research potential presented by public finds data. Round and oval (also called tortoise) concave brooches (in Finnish kupurasolki) are a characteristic object of the period. Round concave brooches were in use throughout the Viking Age (AD 800-1050), while oval concave brooches (not to be confused with the Scandinavian oval type) became popular from the end of the Viking Age and into the Crusade period (AD 1050-1300) (Appelgren 1897; Ailio 1922).The round brooch type is unique to Finland, and has been interpreted as a manifestation of strong regional identity that distinguished southern Finnish female dress from the rest of the Baltic Sea region (Gustin and Wessman 2021, 61).

A typical Finnish female dress consisted mainly of copper-alloy objects, which was the most widely utilised metal in Finland during the Iron Age. As Finland had no sources of non-ferrous metals of its own, these metals would have been imported to the area. Melting and recycling scrap metals into new objects was probably also common. Women would wear a pair of concave brooches that fastened the dress over the breasts, with a third brooch in the middle fastening the undergarment. Elaborate chain arrangements were fastened between the brooches, and from these chains hung different kinds of pendants, bells and personal care accessories such as ear spoons and tweezers. As noted, these dress ornaments became heavier and larger during the Viking Age (Raninen and Wessman 2015, 296).

The round concave brooches in Figure 8 serve as a good example of how metal detecting is providing archaeology with completely new information, not only from burial contexts but also from ritual deposits and caches. This set of brooches appears to be in mint condition and was probably not worn before being placed in the ground. It is therefore not from a burial context. During a small archaeological test-excavation at the find spot later the same year, two chain-holders and ten pieces of chain links were found in the same pit as the brooches. Close by, in other test pits, pottery and burned bones from pike, perch and black grouse were found. The site was interpreted as some kind of a settlement site dating to the 11th and 13th centuries (Pesonen 2021), although the authors believe the possibility of a ritual site should not be excluded.

According to Edgren over 320 round concave brooches had been found in Finland by the early 1990s (Edgren 1992, 242); this is probably based on a rough estimate of grave goods from excavated inhumation burials. So far public finds have contributed a further 207 round concave brooches and 42 oval concave brooches, with Figure 9a mapping their geographical distribution. From the older excavated evidence we know that round concave brooches (pink dots) are characteristic of south-western dress assemblages, whereas oval concave brooches (black dots) have been associated with eastern styles (Ailio 1922, 5; Raninen and Wessman 2015, 296). This pattern is confirmed and refined by the public finds data, though its visual representation requires some thought. Point-based distribution patterns are difficult to interpret visually, especially when locations are clustered or stacked, and kernel density 'heat map' surfaces would similarly be hard to compare considering the overall pattern inevitably concentrates in Häme and the south-west. We have therefore opted to summarise and compare these spatial distributions with Standard Deviational Ellipses. Mathematically calculated from spatial point clouds, they essentially simplify the two brooch type distributions and represent their geographic weight and direction. These were produced on the Open Source GIS program QGIS v. 3.42.1-Tisler, using the Standard deviational ellipse plug-in tool.

While the excavated archaeological evidence for these well-known brooch types has not been subjected to a similar GIS analysis (nor has the material been properly digitised, though some 90 excavated concave brooches are recorded in the AADA database: Pesonen et al. 2024), the understanding has long been that there is an east-west divide. The new finds data confirms it. From this analysis we can see a clear western focus for the round concave brooch types, concentrating solidly around the numerous findspots in the regions of Häme and Southwest Finland. Even though the majority of all the metal-detected finds data comes from the same regions, the distribution of oval concave brooches is wider and clearly drifts east. It is most likely that the picture will be clarified should more finds come in and be processed from central and eastern Finland, as it is still vastly under-represented in the current data. The overall picture confirms that we can detect regional patterns in material culture even from the geographically biased and still limited, if growing, amount of Finnish public finds data.

Almost half (20 out of 42) of all oval concave brooches recorded as public finds since 2000 have been recovered west of Lake Päijänne in Päijät-Häme, and a spatial analysis of their findspots shows that their relationship with the geography of long-distance travel differs from those of round brooches.

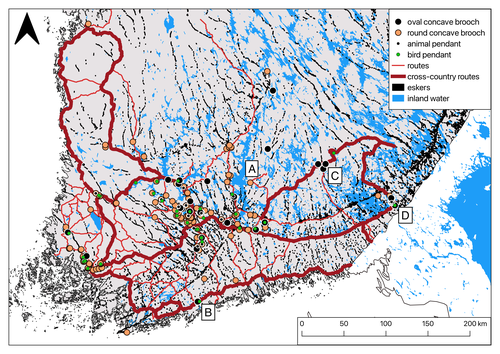

Figure 10 shows the distribution of round and oval concave brooches (as well as bird and animal pendants, see Section 4.3) in the southern half of Finland. We compare this distribution to data created by a recent interdisciplinary GIS-led study into historical long-distance communications in the region of Finland (Rantanen et al. 2021). The map shows a selection of late medieval long-distance routes, with major historical cross-country thoroughfares highlighted in bold. As with the mapping of Iron Age archaeological sites and medieval settlement patterns we approach this as a necessarily rough (if important) model that collates current understanding into a visually and computationally useful summary. New and more fine-grained data on the historical road and travel networks in Finland will be forthcoming from the outputs of two GIS-led projects into historical roads and routes that have received funding from the Kone Foundation and the Academy of Finland (cf. Oksanen et al. 2023; Salminen 2023 for introductions to the projects).

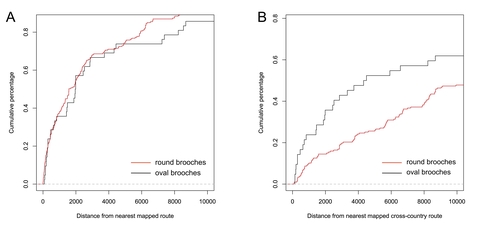

The majority of round and oval brooches have been recovered in the vicinity of the routes as mapped by Rantanen et al. 2021, with some recovered very close to each other. Figure 11a is an Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function calculation that computes the percentage of brooch findspots to the nearest mapped route line along a continuous spatial scale (calculated using the ecdf function of R's base stats package: R Core Team 2021). For example, over 60 per cent of all brooches of both types are recovered within 3000m of these routes. There is, indeed, no significant difference in their respective distributions. What little variance there is between the two graph lines largely arises from the relative granularity of the calculation, as there are five times more round than oval brooches recovered. A two-sample Anderson-Darling test for statistical significance (twosamples package: Dowd 2023) between the two distance-to-routes calculations supports this with a result of p = 0.195, meaning that the null hypothesis of these two samples (i.e. the cumulative distances of each brooch type to the nearest route line) being drawn from the same distribution cannot be confidently rejected. We set the p-value threshold to 0.05.

In other words, in the context of their spatial relationship with all mapped routes, the deposition pattern of these two brooch types cannot be shown to have been significantly dissimilar. This can be taken as simply reflecting settlement distribution during the Late Iron Age: brooches are found near routes, routes connected settlements, and dress accessories were typically lost or deposited near where people lived. The analysis intriguingly suggests that a significant sample of the mapped late medieval regional and inter-regional routes — even beyond uncontroversial candidates such as post-glacial ridge routes — are indeed of prehistoric origin. Though beyond the scope of this article, further work deploying computational methods on metal-detected data, and on other archaeological and historical GIS data, has the potential to considerably advance the scholarship on prehistoric and historic travel and communications in Finland.

This spatial distribution, however, is different if we only consider major long-distance cross-country routes. Figure 11b shows an ECDF calculation that compares the two brooch distributions with only the main mapped cross-country routes as identified by Rantanen et al. 2021. Again, one must approach such route typologies with care, since it is naturally very difficult to model a given route's relative use intensity during prehistory. But for the purposes of this analysis, we would consider both the strong statistical results as well as the broad-level identification of these routes as sufficiently secure. As can be seen in the graph, the distributions are now clearly different, with the oval brooches being located on average significantly closer to route lines. Almost 50 per cent of all oval concave brooches are located within less than 3km of main routes and therefore can be considered to originate from population centres adjacent to them; especially since many brooch finds are thought to come from cemeteries, and these in turn were usually situated close to the settlements they belonged to. By contrast the percentage of round concave brooches recovered this close to major routes is less than half, at under 20 per cent. An Anderson-Darling test for the two distributions gives p = 0.0025, a result that allows us to reject with confidence the null hypothesis that the two samples come from the same statistical distribution.

It would seem very likely that in the context of long-distance cross-country movement, the processes that led to the deposition of these two brooch types diverged. The history, origin and circumstances of each discovered prehistoric archaeological object will have been different, and the identities of their owners have passed beyond the veil of knowing. In aggregate, however, our hypothesis is that oval concave brooches recovered in south-western Finland, owing to their relative nearness to major east-west transport routes, connect to the historical movement of individual peoples. Perhaps these were eastern Finnish women marrying into and settling among western communities, and bringing their dress ornaments with them? For example, in the city of Espoo (close to Helsinki on the southern coast, see Fig. 10) metal detecting has shown that the majority of the Late Iron Age finds are of the so-called eastern Finnish type (oval concave brooches, animal pendant and chain holders), which is striking. Although the find material is so far scarce, it suggests that there was indeed a female community living there dressed in a costume that has direct parallels with the Tuukkala inhumation cemetery in Mikkeli (Fig. 12), near one of the early settlements centres in eastern Finland (Wessman 2016, 26-27; 2022, 49-50).

Metal-detected finds have therefore brought out new evidence of long-distance contacts and the use of local and imported objects in female dress ornament ensembles. We will next look at the use of 'eastern-style' pendants worn by women during the Late Iron Age. First, it appears that certain pendants, like oval and round concave brooches, had distinctive regional distributions; second, the finds provide new angles into thinking about prehistoric long-distance connections and the use of imported artefacts for display and even ritual purposes.

During the Late Iron Age, the two most common pendant types are bird pendants and the so-called Fenno-ugrian 'plastic' animal pendants. Although there are several different variants of bird pendants (e.g. see Fig. 14), the majority of those from the Viking Age depict some sort of water bird or a hen/rooster, often flat and perforated with pointed claws and a widening tail (Kurisoo's type C1.3). These are most frequent in Estonia and northern Latvia and thus are probably a local expression of their Russian counterparts (Kurisoo 2021, 99-101). It may be that these pendants have come to the area now know as Finland as exports via Estonia. Their geographical distribution is mainly in the south-west.

The 'plastic' animal pendants consist of a hollow horse body with short chains linked to 'bird feet' (see Fig. 13). They were most frequent in the Votic areas (Ingria) of present-day north-western Russia during the 12th and 13th centuries (Kurisoo 2021, 105, 107) and in the Savo-Karelian region of Finland, often hanging from the female dress together with an ear spoon. They are also found in northern Finland (Hakamäki and Ikäheimo 2015) and in Sápmi, at sites of clear Sámi origin (Jarva et al. 2001). The water bird-like feet elements in these animal pendants are probably influenced by ornament expressions from the Permian areas of the Upper Kama River in Central Russia, which we will come to later (Uino 1997, 166-68,186).

Figures 9b and 9c show the distributions of 36 bird pendants and 25 animal pendants recovered by members of the public. Their broad contours match those of, respectively, round and oval concave brooches, and appear to represent parallel patterns in Late Iron Age female dress representation. Very little was known of the geographical distribution of these pendants before they began to be found by metal detecting, so at a national scale they represent a new class of evidence. They are, furthermore, linked to eastern long-distance connections during the Late Iron Age.

To understand how these animal ornaments became popular in Finland, we need to look at phenomena such as the fur trade and political gift-exchange, which probably supported the economic prosperity of the settled areas of Late Iron Age Finland. Their inhabitants had excellent hunting and trapping opportunities in the boreal hinterlands of the Finnish lakeland districts and further north (Raninen 2020; Kirkinen 2019). Direct water routes ran from the western coast of Finland to Häme and from there eastwards (Edgren 1992, 249), and the intensification of settlement in different parts of Finland — such as in Savo, Karelia and northern Finland — during the Viking Age has been connected to this hunting and trade activity (Taavitsainen 1990, 112-13). Contacts with the areas of the upper Kama and Vyatka rivers (in present-day central Russia), strengthened during the Merovingian period (AD 550-800) and the subsequent Viking Age. It was probably Finnish elite groups that became involved in far-reaching trade or gift-exchange on the Volga River (Callmer 1980, 209 with references; 2015; Raninen and Wessman 2015, 270). The outcome of this network is shown by small finds deriving from the Lomovatovo, Glasov and Nevolino (often called 'Permian') cultures, found from several places in Finland (Carpelan 2006, 87-88; Callmer 2017, 159-62; 2024).

Previous studies have shown that objects acquired from remote regions were desirable and actively used in the ideological legitimation of the group controlling their acquisition, distribution and use (Gustin 2016, 53, with references). 'Permian' objects in Finland would have been used by those who had active contacts with the peoples of the Kama and Volga regions. As discussed, metal detecting has in recent years revealed many new objects belonging to these so-called Permian types in the regions of Häme, Southwest Finland and North Ostrobothnia. One spectacular example is the unique three-headed eagle pendant (KM 40913:1, see Fig. 14) that was found in 2015 by the KHME detectorist club at the small island of Pohto, part of the Laukko manor, in Vesilahti. The landowner, also a metal detectorist, found a Permian sun pendant (KM 42288:2) only 50cm from the eagle pendant soon afterwards (Mikkola 2009; Mikkola 2021). These two objects might have been ritual offerings, suggested by their location under a large stone and in close proximity to water.

On the level of individual finds sites it may also be significant that a highly unusual clustering of round (4) and oval (8) brooches, as well as of bird (1) and animal (2) pendants, have been recovered within a dozen kilometres of the town of Ruokolahti in eastern Finland (see Fig. 10). An Iron Age settlement site and seven cremation cemeteries have been identified within this same area. The area is located at the intersection of the south-easternmost corner of the Saimaa lake system with the post-glacial ridge system Salpauselkä I, thought to have been a major cross-country route through southern Finland. Here these land and water routes also approached Lake Lagoda and the Eurasian travel routes connected to it.

Such rich findings hint at the significant potential for new archaeological understanding through metal-detected data, in particular in eastern Finland, and with the hope that a more detailed picture will emerge in the future through the reporting and recording of new finds. Methodologically, the larger point we wish to convey is that the new metal-detected data empowers novel qualitative assessments combined with quantitative computational and large-scale spatial approaches that have been, so far, underused in Finnish archaeology.

Metal-detected finds and responsible metal detecting have considerable potential to advance archaeological and cultural heritage research in Finland on several fronts. First, as has been demonstrated by the scholarship discussed in this article and by our new research, metal-detected (and other public) finds have brought to light new information about past material cultures. They have especially changed our understanding of the Finnish Iron Age. Furthermore, instead of principally focusing on individual detector finds, we argue that there is considerable unexploited potential in spatially and temporally large-scale analyses using methods developed for archaeological 'big data' research.

Geographical analysis of the finds data, for example, suggests that individual female dress ornaments were combined in a nuanced manner during the Finnish Late Iron Age. Although the large and attention-catching female brooches can be interpreted as expressing a core regional or ethnic identity, pendants and other hanging ornaments could perhaps be attached to the dress ensemble in a manner that expressed more individualised identities. For women that had moved between core cultural regions, could these even have represented personal processes of social assimilation, of negotiation between their original and adopted socio-cultural milieus? This is still a work in progress, but we believe that the newly increased availability of material culture creates new possibilities and avenues for research, whether in terms of understanding large-scale demographic structures, regional material cultures, or the use histories of particular object types.

Second, metal detecting has brought to light the need to renew the typology for the Finnish Iron Age, which is over half a century old (Kivikoski 1973). We believe that there is potential through the new datasets to make adjustments to the common periodisation boundaries based on object typologies; for example, the years AD 800 for the beginning of the Viking Age, AD 1050 for the beginning of the Crusade period, and AD 1300 for the end of the Iron Age and the beginning of the medieval period. For many artefact types, of course, it may never be possible to construct new typologies without information from controlled archaeological excavations. But numerous examples from elsewhere in Europe (e.g. Cool and Baxter 2002; 2015; Kars and Heeren 2018; Carpentier 2022; Deckers et al. 2021) show the enormous potential of large quantities of metal-detected objects in advancing hitherto relatively underdeveloped fields in archaeological object studies, or in substantially revising previously held orthodoxies.

Third, we note that regardless of the personal and often complex opinions Finnish heritage and academic professionals (including the authors) may harbour, legal archaeological metal detecting has over the last decade developed into an important scientific and cultural activity in the country. Barring a major change in the law governing archaeological cultural heritage, this is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. Responsible metal detecting will, therefore, continue to represent a major source of new archaeological information, including in regions and of types of material culture poorly captured by excavated evidence. The importance of stray finds archaeology is only heightened by the fact it represents a substantial part of the total of new finds material that arrives to the FHA's collections, as in the current funding environment the Finnish professional and academic heritage establishment lacks the resources to conduct many research excavations.

To conclude, the material produced by metal detecting represents a highly complex body of data, and a successful analysis is contingent on a qualitative appreciation of the modern processes that have produced it. These include the behaviour and interests of the detectorists, but also institutional digital data management priorities, infrastructures and workflows. Yet, despite these challenges, as we have shown, the scientific value of the finds data is evident; moreover it invites the promulgation of underexploited computational and quantitative perspectives in Finnish archaeological research. Finally, public finds data not only holds considerable potential in advancing archaeological knowledge, but also has in the past half a decade represented an opportunity to develop the Finnish digital cultural heritage infrastructure (Wessman et al. 2019; Hyvönen et al. 2021; Rohiola and Kuitunen 2022; Oksanen et al. 2024). At a deeper level, continued reflections on the data being gathered will support the ongoing redevelopment of the ontological framework — both in the term's philosophical and technological senses — of Finnish archaeology to better meet future needs.

Eljas Oksanen's work on this article was supported by funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 896044. Taika-Tuuli Kaivo digitized the public finds information recorded in 2000-2015 into the Muinaiskalupäiväkirja, funded by Oksanen's Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant and financing from Suzie Thomas' professors' starting grant; we would like to thank Taika-Tuuli Kaivo for her work and Suzie Thomas for her support of the project. We would like to thank Timo Rantanen, Jenni Santaharju and the BEDLAN research group for making available to us their forthcoming GIS data on the reconstruction of the Finnish historical route network. The authors would also like to thank the Finnish Heritage Agency for their support and cooperation with the article project, Michael Finnberg for the permission to use his image, and all the Finnish metal detectorists engaged in responsible and responsive detecting, without whom this new research into our shared past and common archaeological heritage would not be possible.

The data on Finnish public finds from the Muinaiskalupäiväkirja finds lists and from the database of the Luettelointisovellus used in this article is published on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15263478

1. FHA data dump from the Luettelointitietokanta database obtained on 8 May 2023. The older finds lists were digitised from Muinaiskalupäiväkirja data service PDF finds lists in a project led by one of the authors. A dataset combining the Luettelointitietokanta and Muinaiskalupäiväkirja public finds discussed in this article is published on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15263478←

2. The finder's fee in Finland is not based on market value as, e.g., in the UK (https://finds.org.uk/treasure).The monetary value of a find is not determined with reference to set guidelines and is more of an agreement between the finder and the FHA. The exception is if the artefact is made of precious metal, in which case the minimum fee value is calculated from its base metal value increased by 25 per cent (https://www.museovirasto.fi/en/collection-and-information-services/item-collections/mitae-teen-kun-loeydaen-muinaisesineen). In other countries, for example in Norway, the finder's fee is more transparent and divided into four categories (from 0-2000NOK) with an exception for precious metals (https://riksantikvaren.no/veileder/finnerlonn-oversikt-over-verdigrupper/).←

3. The international scholarship that has studied the matter appears to be still quite poorly circulated in Finland. In an encouraging sign of change, however, the current draft for the revised archaeological cultural heritage law separates and facilitates object recovery by recreational metal detecting in actively ploughed soil layers from most other contexts: see pages 173-4 and §28, page 298: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/165219←

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.