Cite this as: Bryant, S. and Dupuis, M. 2025 Archaeology in the Changing Townscape: The Centre Region in France, Internet Archaeology 70. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.70.12

With an emphasis on the example of Chartres, this paper will provide some of the historical context and regulatory framework that governs urban archaeology in this region of France. It has also taken on board some of the reflections and questions raised by many of the case studies presented during the 25th Europae Archaeologiae Consilium (EAC) symposium in 2024. Comparisons within a broader European context shed a sometimes harsh light on the strengths and limits of the policies and practices of archaeological excavation and resource management in the Centre region of France.

Up until 2016, the Centre region was one of the largest of the 22 metropolitan regions of France, comprising 6 of the 96 metropolitan departments (Figure 1). The regional reform of 2016 then reduced the number of metropolitan regions to 12, by amalgamating many of the smaller ones, leaving the newly named Centre–Val de Loire (CVDL) as an average-sized region with an area of 39,151 km² and a population of 2.57 million (Table 1), compared to, for example, the 30,688km² and 11.75 million habitants of Belgium. The region displays great disparity in terms of population distribution and economic activity, with a preponderance in the northern part of the territory, strongly influenced by the proximity of Paris and its suburbs, the Loire valley, and a dense network of motorways (Figure 2).

| Department | Capital | Surface area (km | Population (2023) | Population density (habitants/km²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 – Cher | 0 | 7235 | 0 | 41.41 |

| 28 – Eure-et-Loir | 0 | 5880 | 0 | 73.37 |

| 36 – Indre | 0 | 6791 | 0 | 32 |

| 37 – Indre-et-Loire | 0 | 6127 | 0 | 99.92 |

| 41 – Loir-et-Cher | 0 | 6343 | 0 | 51.79 |

| 45 – Loiret | 0 | 6775 | 0 | 101.05 |

| TOTAL | 39,151 | 2,573,600 |

The central government is represented in each of six departments of the CVDL by a departmental prefect, who implements government policy. The regional prefect represents the prime minister and each ministry for which the services have been 'de-concentrated' (but not decentralised) at the regional level, and is based in Orléans, the regional capital. While the departmental and regional echelons represent central government, the role played by the departmental prefectural services in promoting the economic development of the regions within their department can lead to tensions with the central governmental services at the regional level.

The legal and regulatory frameworks surrounding heritage management are complex, often overlapping, and currently evolving with respect to the increasing power of environmental regulations. It is outside the scope of this article to present them all here. However, it is necessary to understand the general framework governing archaeological heritage management, excavation work and research, which is administrated by the Ministry of Culture under the authority of the regional prefect.

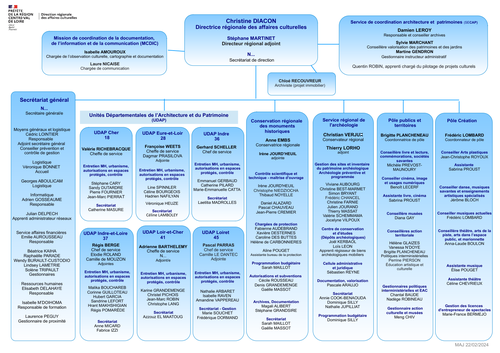

The ministry is represented by the Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles (DRAC), responsible for the implementation and coordination of the state's cultural policy with regard to heritage, museums, the visual and performing arts, and cultural and artistic education (Figure 3). DRAC provides financial assistance through subsidies and grants, as well as guidance and expertise for cultural institutions in local authorities and the private sector. Heritage management is concerned with architectural heritage in general, including grade 1 and 2 listed buildings, archaeology, archives and the curation of museum collections of all types.

Architectural heritage and historic monuments are managed by the Conservation Régionale des Monuments Historiques (CRMH) for listed buildings, while the Unités Départementales d'Architecture et du Patrimoine (UDAP) is responsible for the maintenance of listed buildings and implementing town planning regulation in protected heritage areas. Outside these areas, building permits are granted by local authority planning departments. These may cover several levels, from a single commune to a community of communes, both rural and urban. The Service Régional de l'Archéologie (SRA) is tasked with implementing the law and government policy concerning archaeological heritage. Its remit includes maintenance of the sites and monuments register (SMR), promotion of archaeological research through aid to research projects and publications, scientific evaluation of archaeological activity within the region, and preservation of archaeological resources. With the massive increase in urban and rural development since the 1990s, and the effects of the laws of 2001 and 2002, archaeological protection deriving from development projects has become the single most important activity of the SRA.

The principal development projects in the region are quarries, industrial estates and logistical buildings, road building and urban development. Without going into the somewhat tedious details of how development applications are selected and processed, the projects undergo a desk-based assessment by the SRA, in order to determine any potential impact on archaeological resources, and implement appropriate conservation measures.

It is interesting to note that the French system has a distinctly medical tone with, as a first step, the prescription of a diagnostic test designed to detect and characterise any archaeological remains present within the perimeter of a project. This test may be carried out by a regional archaeology service, if one is present, or by the national operator, the Institut National des Recherches Archéologiques Préventives (INRAP). Depending on the results of the test, detailed in a report that has to meet a certain number of criteria, the SRA must decide whether the remains are sufficiently important and/or well preserved to justify further conservation measures: either preservation in situ through modification of the development project (freezing the site or mitigation strategies), or by recording during excavation. In the first case, after discussion with the developer, the SRA lays out the material conditions for the protection of the remains. In the second case, the SRA prescribes an excavation (fouille préventive) of which the objectives and methodological principles are detailed in the brief attached to the decision (arrêté), signed by the regional prefect. In both cases, the conservation measures and brief are examined by an independent scientific committee, the Commission Territoriale de la Recherche Archéologique (CTRA), which meets ten times a year.

The CVDL region boasts six local authority archaeology units (Figure 4 and Table 1). Three offer departmental services, and the others are attached to the municipality of Orléans, or the urban communities of Chartres Metropole (66 communes) and Bourges (17 communes). Orléans, Chartres and Bourges were the major historical towns of the region during the Roman and medieval periods, and all three have proven to have late Iron Age origins. Tours should also belong to the list but represents a strange anomaly with regards to archaeology (see below). The departmental services were created between 2005 and 2008 as a means of maintaining some control over the costs and schedules of archaeological excavations related to development projects carried out by the relevant local authority.

The municipal archaeology services have a longer history in all three cases, and their origins can be traced back to the scholars, engineers and learned societies of the mid-19th century. For the Centre region, the early period of urban development in historic town centres between the 1970s and 1980s was marked by an absence of any real policy for heritage management and appropriate infrastructure to carry out rescue excavation. Up until this date, urban excavation was largely research based and carried out by local archaeological societies or university teams. For Chartres, the Roman and Iron Age sites of rue Saint-Thérèse à Chartres illustrate this situation. Excavated using the Wheeler method by Pierre Courbin between 1967 and 1972 (Figure 5), the sites were taken on by Groupe de Recherche Archéologique de Chartres (GRAC) until 1976.

The absence of permanent organisations with adequate finances led to the destruction of many archaeological sites, that of the Campo Santo medieval cemetery in the centre of Orléans being an emblematic case. The ensuing public scandals caused by these losses led to an increased awareness of the value of archaeological and architectural heritage, and contributed to the rapid development of rescue excavations, often carried out by local associations and volunteers. These operations led to improved attitudes to archaeological remains by developers and public authorities, but the existing legal framework, aimed originally at regulating research excavations carried out by the state, was rapidly overwhelmed by the sheer volume of activity.

One answer to this situation was the creation, in 1973, of the Association des Fouilles Archéologiques Nationales (AFAN), to carry out rescue excavations at the request of the state. This was in reality the first step towards the necessary professionalisation of archaeology, although to the detriment of the associative framework, which allowed the public to participate in the discovery and conservation of its own heritage.

In the case of Chartres, Dominique Joly became the first municipal archaeologist in 1975, with the creation in 1978 of the Association pour la Défense de l'Archéologie Urbaine à Chartres (ADAUC) in order to meet the needs of the first developer-funded excavations. Throughout the 1980s, Chartres, Orléans and Bourges were laboratories for the development of contemporary methods in archaeological excavation and recording. Between 1989 and 1992, AFAN and ADAUC jointly carried out two major excavations in the cemetery of Saint-Chéron and the Esplanade of the Cathedral (Figure 6), and the city of Tours became the seat of the Centre National de l'Archéologie Urbaine (CNAU), created in 1984 as an observatory and research centre for urban archaeology in France. However, despite the presence of this institution and a university offering master's and PhD level archaeological teaching with its own training excavations, Tours never had an operational archaeology unit, regardless of its major historical and archaeological potential. The dissolution of CNAU in 2016, and the transfer of its documentary resources, one of the most important in France, to the Médiathèque du Patrimoine in Paris, was the final chapter of the saga (Garmy 2016). Archaeological work is now carried out by INRAP or the departmental archaeology service.

2001 marked a turning point for the regional archaeology units, with a major change in the laws and procedures governing developer-funded excavation. The new law provided a clear legal and financial framework that obliged developers to pay for archaeological work, and transformed AFAN into INRAP, a quango under the joint tutelage of the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry for Scientific Research. It should be noted, however, that the latter has been largely absent in terms of financial and scientific backing, leaving the Ministry of Culture as sole support for INRAP.

Initial archaeological evaluation work (diagnostic) was to be carried out by INRAP and financed by a fee (redevance) based on the surface area of the development project. Any subsequent rescue excavations were to be paid for by the developer. The law excluded local authority archaeology services from the system, instating a de facto monopoly for INRAP. It was modified in 2002 to bring rescue excavations into the commercial sector. Henceforth, INRAP, local authority units, and private operators with the required accreditation, could submit competitive tenders for excavation work. The other major change was that regional excavation units could now carry out diagnostics in the same way as INRAP, even having priority over the national operator for sites in their own area. They also received a subsidy from the redevance based on the surface area and type of stratigraphy present. Unfortunately the method used to calculate the subsidy had several shortcomings, which failed to compensate properly for the real costs of stratified urban sites, and induced a threshold effect that made rural evaluations 'unprofitable' over a certain surface area. The parameters have been changed recently in order to address these issues, albeit partially.

The new law therefore gave an increased role to the local authority units, enabling them to develop a stronger permanent team with a high level of activity (Table 2). This was particularly visible in Chartres, which benefits from very strong political support from both the municipality and urban community. ADAUC became the Service Municipal d'Archéologie in 2001, with a team of seven permanent staff members in 2003. This rose to 87 in 2005, with the first 100% 'in-house' excavation of the 'Cinéma' site in 2005 (Figure 7), and reached a peak of 100 personnel in 2006. The service stabilised at around 40 permanent staff from 2014, while their region was expanded to cover all 66 communes of the urban community of Chartres in 2018.

| Regional service | Date created | Territory covered | Number of permanent (and temporary) staff in 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conseil Départemental du Cher | 1987–2020 | Department of the Cher | 3 |

| Conseil Départemental de l'Eure-et-Loir | 2005 | Department of the Eure-et-Loir | 18 (variable) |

| Conseil Départemental de l'Indre-et-Loir | 2005 | Department of the Indre-et-Loir | 8 (variable) |

| Conseil Départemental du Loiret | 2008 | Department of the Loiret | 3 in 2009, 12 in 2018 (variable) |

| Pôle Archéologique de la Ville d'Orléans | 1992 | Municipality (possible extension to an urban community of 20 communes in the future?) |

8 (>8) |

| Bourges Plus | 1983 | Municipality (1983–2006) Urban community of 14 communes from 2002 |

8–10 |

| Chartres Métropole | 1978 | ADAUC (1978 – 2002) Municipality from 2002–2018 Urban community (66 communes) from 2018 |

21 in 2018

41 in 2024 (>10) |

| Centre National de l'Archéologie Urbaine (CNAU) | 1984–2016 | Observatory and research centre for urban archaeology in France | 3–4 |

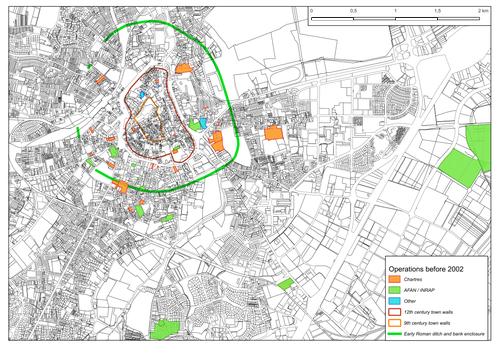

The evolution in the laws was partly triggered by changes in developmental policy. After a period of large-scale redevelopment of historic town centres, new developments tended to shift towards the outskirts of urban centres, with the creation of housing and industrial estates and large infrastructure projects. For Chartres and its surrounding area, this shift can be seen in the map of archaeological operations carried out before 2002 (Figure 8) and after this date, notably between the periods 2002–2017 and 2018–2023 (Figures 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14). With the growing importance of developer-funded excavations, this tendency changed the aims of archaeological research, at least for the national operator. With a focus on large-scale excavations over extended regions, excavation and recording methods changed, often with a loss of knowledge in the approach to highly stratified sites, as practitioners progressively left excavation work or moved to regional or private operators. However, the municipal archaeology units were able to maintain some level of activity within the historical urban environment, thus preserving their savoir-faire.

The growing awareness of the environmental and social challenges posed by urban sprawl, vehicle traffic and climate change has started to modify our vision of the town and how it should be developed. One of the consequences has been a marked increase in the density of the urban fabric and the renewal of old town centres, encouraged by governmental projects designed to improve their appeal. This tendency is set to continue for the foreseeable future, since the Zéro artificialisation nette (ZAN) law was passed on 20 July 2023, which aims to stop completely any development of new land by 2050, with a 50% reduction in greenfield developments by 2031 as an intermediary goal.

This overall trend can be seen in the major towns of the Centre region, although there is still a certain tension between the urban centres and their suburbs. Overspill from the region of Paris and the dense network of motorways mean that development activity is still set to remain at a high level in the outskirts of agglomerations. At the same time, building activity within the town centre and its immediate suburbs has increased over the last few years, particularly since the COVID crisis. For Chartres, this situation is likely to persist over the next few years, with the planned extension of industrial estates to the east of the town and other major projects in the pipeline. This prognosis will certainly evolve, however, as the number of building permits received by the SRA this year seems to have diminished, possibly linked to an apparent downturn, or at least a stabilisation, in the property market. Nevertheless, the archaeology service has maintained a high level of activity since 2021, and still has to adapt to the different methods and approaches needed by large open-area excavations while maintaining and developing those specific to a deep and dense stratigraphy in a complex urban environment.

At a regional level, the figures regarding the number of operations carried out by regional units (Figure 15, 16, 17, 18) clearly show that these bodies play a key role in the archaeological landscape, with several advantages for the local authorities. By taking on evaluation and excavation work, they are able to meet deadlines that would be impossible for the national operator (INRAP), while also minimising overall costs as a result of largely 'in-house' management of resources. By providing a clearer vision of delays and costs to potential developers, they are a positive influence on maintaining the economic attractiveness of the region. For infrastructure projects led by the municipality or urban community, the archaeology service plays an important advisory role at the earliest possible stage of any development project, through to the integration of any archaeological work into the overall project schedule. This also applies to projects led by private developers, where the regional unit may act to facilitate contacts with the SRA. Through their respective and complementary actions, archaeology has gone from being perceived and experienced as a purely unwanted obligation to being an integral part of town planning and development. Its role in the urban environment is particularly evident, as it can be advantageous for local decision makers by facilitating the planning process and development projects.

The integration of archaeological remains into urban development projects still remains fairly marginal, and is generally limited to heritage management projects specifically aimed at presenting remains to the public in the context of a museum, visitor centre, or the archaeological 'crypts' under the floors of several major churches such as the cathedrals of Bourges, Chartres and Orléans. With regard to sites discovered in the context of urban development projects, the integration of remains into the final 'product' is very rare, limited to well preserved or spectacular masonry constructions. The most obvious examples are elements of urban defences, such as the bastion of the Place des Epars in the underground car park at Chartres, or the walls of the Saint-Pierre-Lentin church under the regional council building in Orleans. In most cases, the remains are either excavated, and thus destroyed, or preserved, with varying degrees of success, through mitigation strategies. These generally consist of limiting the depth of the construction, and limiting the number or changing the arrangement of the foundations, so as to limit the overall impact.

Above ground, architectural heritage may benefit from a range of protections, while the urban fabric may be preserved for small-scale developments, simply because the forms of certain Roman-period monuments and a high proportion of medieval property limits are still fossilised in the land registry (cadastre). However, the tendency to increase urban density goes against this, by encouraging the amalgamation of land plots for larger and taller buildings. While historical architectural heritage benefits from the protection offered by a certain number of legal frameworks, the preservation of buried remains depends primarily on their economic impact on the development project. There has yet to be an equivalent in the CVDL region of the case study of Lübeck, presented by André Dubisch (this issue), where the developers had an obligation to respect the spatial organisation, including the volumes and external aspects of contemporary constructions, and effectively recreate the lost medieval urban fabric.

This particular example illustrates the importance of an active planning policy by local authorities. It also raises the question of the real effectiveness of a highly prescriptive approach to town planning and building regulation. While urban communities play a pivotal role in planning the overall organisation of the urban environment and its infrastructures, much of the initiative for its materialisation is left to the property developers. In this situation, the role of archaeology is reactive, responding to the external forces of urban development, with a fairly limited impact on the overall policy.

In a more active role, archaeology is a major force in developing public awareness of the value of archaeological heritage, which has helped shape the environment in which people live. The progress accomplished in this is the result of the long-term and permanent presence of regional archaeology units and their research and outreach activities. It is therefore worth taking a look at some aspects of these, to appreciate the multi-faceted roles that archaeology fulfils.

France was among the first European countries to have a national SMR database, initially with SIGAL, which became Dracar in 1978, the same year that the ministry created databases for museum collections, archives and architectural heritage. In 2002, Dracar migrated to the current system (Patriarche), which runs under Oracle, and was linked to the ArcView and then the ArcGIS program. A new version was delivered in 2005 (Fromentin et al. 2006; Chaillou and Thomas 2007). Its four modules allowed the creation of entries linked to geometries (point, polyline, polygon) for archaeological entities, perimeters of protected sites or areas, archaeological operations, and documentary sources. It was also connected to a search engine (Business Objects) that allows complex data analysis. Patriarche was run by dedicated staff in each SRA, who mapped and documented archaeological sites discovered by excavation, chance finds and remote sensing, as well as by the various archaeology operations carried out in their respective departments. This ensured regular and consistent data entry.

The increasing weight of rescue archaeology in the SRA's activity from 2002 onwards led to a gradual transfer of the SMR's maintenance from dedicated teams to the individual agents already tasked with the management of their department. This inevitably led to increased discrepancies in the quantity and quality of the recorded data. The system also suffered from a lack of investment in the associated tools, with ArcGIS left at version 3.3 running on a virtual Windows XP environment, compared to the current version of 10.8.2. The descriptive vocabulary has similarly remained unchanged, with a number of minor but annoying glitches left uncorrected. The centralised control of the system means that the SRA has not been able to benefit from the rapid evolution of open-source geographical information system (GIS) programs such as QGIS, despite government directives in favour of open-source programs.

Despite its shortcomings, the current environment of Patriarche remains the principal GIS tool for heritage management within the SRA, especially for dealing with public information requests from developers, who want to know whether their project is likely to be subject to archaeological work or restrictions. The digital version of the SMR can be consulted by the public through the Atlas des Patrimoines, which is hosted online by the Ministry of Culture. The public only has access to a map of the perimeters that are archaeologically sensitive, or those where any development project may be subject to archaeological prescriptions.

It is not possible to consult the database for existing archaeological sites and operations for several reasons. Firstly, the register is constantly evolving and, for the urban environment, it simply does not have the necessary data for an accurate judgement of the archaeological potential of any given plot of land. Public access to raw data or site maps runs a very real risk of poor interpretation and the belief that the absence of a known site automatically means that there are no archaeological remains whatsoever. This could potentially undermine any decision to impose archaeological work on any given project.

Secondly, the transition by all government departments from the Lambert II extended coordinate system to the Lambert 93 system has introduced problems with the geolocalisation of many sites. The inherent geometrical distortions of the Lambert 93 system can, in some circumstances, 'move' sites several tens if not hundreds of metres. This is less of a problem in urban areas, where mapping is done at the level of the individual land plot, but it becomes rather more problematic for sites over an extensive rural area. Staff shortages mean that the verification of the geolocalisation of many sites can only be done on a case by case basis.

In contrast, the regional archaeology units have been quick to develop their own SMRs, generally starting from data exported from the national SMR. It is worth remembering that the concept of an archaeological database capable of mapping the historical townscape, and of predicting the likely depth and complexity of the stratigraphy, is not new: the Documents d'Evaluation du Patrimoine Archéologique Urbain (DEPAU) edited by the CNAU during the 1980s had already fulfilled this role, with the GIS layers being materialised by transparent overlaying maps (Demolon et al. 1990). Patriarche has, however, been successfully adapted to address the problems of stratigraphy in an urban context in many cases (for example Blois, Tours and Bourges) by linking the GIS to external tables. This has been the result of ad hoc research carried out by local authority units, often as a subject for university diplomas. Many of the 'in-house' systems retain the overall structure of the Patriarche database. Contemporary GIS systems merely make it easier to update, interrogate and visualise the existing data. If the archaeological map of Prague, as presented by David Novák [x-ref], represents a perfect illustration of what an effective urban SMR could be, all three of the French urban archaeology services have developed similar systems that allow the superposition of many layers of data concerning the stratigraphy, presence of cellars and other cavities, industrial sites with a risk of pollution, etc. They also have the distinct advantage of being integrated into the GIS systems of their respective local authorities, which makes any archaeological potential readily visible to the different services responsible for urban planning and development.

Currently, work is underway to set up protocols for the exchange of data between the SRA and the regional services who have invested the means to considerably enrich their SMRs. However, the freedom to conceive and modify their databases according to their needs has brought about the very problems of interoperability and compatibility that Patriarche sought to resolve by imposing a national standard database! In the meantime, regular communication between the SRA and local authority units ensures that decisions concerning archaeological sites are made with the most complete information available.

This exchange is particularly important in the context of the push for all government departments to go 'paper free'. In the near future, development permits likely to affect archaeological remains will be communicated to the SRA by an automated system that will filter each development application on the basis of its geographical situation and predefined criteria (affected surface area, archaeological potential, etc.). This implies the creation of archaeological zones that can be processed by the system. Though the end 'product' is essentially an administrative response designed to meet the needs of the legal framework, the definition of the selection criteria demands a well-researched evaluation of the archaeological context, hence the importance of a well-documented SMR.

As well as taking on archaeological work prescribed by the SRA, regional archaeology services play an active role in the research and publication of archaeological data for the scientific community (e.g. Borderie et al. 2013; Joly 2013), as well as a variety of outreach activities for the general public. The long-standing presence of a permanent regional service, with 50 years of thorough and consistent excavation and recording, has ensured the accumulation of high-quality recorded archaeological data. Taking stock of the potential of this archive, the unit has adopted an active research policy through long-term research excavations and projects designed to reassess the results of previous excavation work.

The preferred 'format' for these projects is a team-based research program, Projet Collectif de Recherches (PCR), which creates a space in which researchers and specialists from different bodies can work together on a guiding theme. Each project is examined by the CTRA and, after a preliminary year, which serves as a test for the feasibility of the project, the PCR is authorised to run on that basis and must include objectives for the publication and diffusion of the results at the end of this period. In practice, and based on the results and motivation of the research team, a PCR can run for several 3-year periods. At the moment, seven of the ten research projects in the department of the Eure-et-Loir are integrated into the scientific activity of the Chartres Métropole unit. Current projects include the Iron Age origins of the Roman town, the Roman wall paintings, of which Chartres has one of the richest corpus in the northern half of France, iron production in the northern territory of the Carnutes, and the topography and evolution of the cathedral chapter. These projects are all, to some extent, related to recent or ongoing excavation work or cultural development projects. The research activity is financed by the urban community, external organisations and the SRA, which can subsidise up to 50% of the overall annual cost of any given project.

If archaeology has a fairly minor impact on urban planning and development policies, it plays a crucial role in providing scientific content for cultural development projects designed to increase the number of visitors and offer an improved cultural experience.

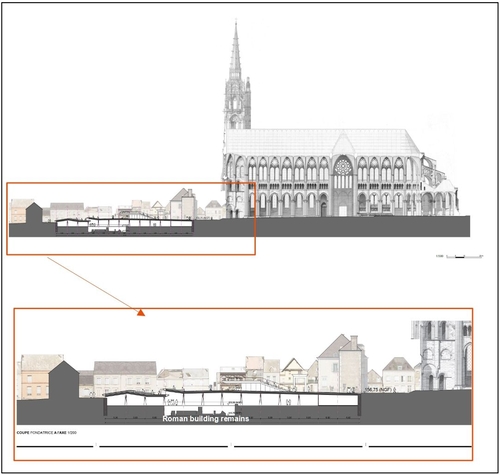

The cathedral of Chartres, a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) heritage site, forms the main attraction of the city, both for the visitors interested in its architecture and stained-glass windows, but also because of the annual pilgrimage at Pentecost (Whitsun), the origins of which can be traced back to the 12th century. Already in 1990, the projected construction of a visitor centre in the cathedral square led to a two-year excavation, which brought to light a site composed of up to 7m of stratigraphy, with the well-preserved remains of a major Roman period building, as well as the foundations and cellars of several canonical houses demolished in the late 19th century (Figure 6). The quality and quantity of theses remains precluded their destruction to make way for the visitor centre, and the initial project was shelved for nearly 20 years. Recent renovation work on the cathedral itself and of the surrounding area has improved its appeal to the public, reviving the original project for a visitor centre, which must incorporate the remains discovered in 1991–1992 (Figure 19). The initial excavation will be reopened and extended to cover most of the western cathedral square. The combined results of these excavations and the PCR centred on the cathedral close will form the core of the scientific project for the centre.

In order to offer a wider choice of heritage sites, and to spread out visitor pressure on the city centre, there is a wish to renovate and better expose the rich stock of timber-framed buildings in the medieval town and its suburbs. This cultural development project has also been extended to incorporate the site of the Roman temple and the medieval abbey of Saint-Martin-au-Val, situated in a neighbourhood at the bottom of the Eure valley, to the south of the historic centre.

A rescue excavation on the site of a series of apartment blocks near the abbey church brought to light a monumental Roman temple complex. This effectively stopped the development project, while the archaeological potential of the remains prompted the creation of a research excavation that ran from 2011 to 2023. This research showed that the temple complex covered some 6 hectares. The discovery in 2016 of waterlogged deposits in one of the buildings led to a prolongation of the research dig, leading to the discovery of three marble-lined monumental basins, with the remains of a decorative wooden coffered ceiling, unique in Europe (Figure 20). This would appear to have burned down during the 3rd century, possible in the context of the destruction of pagan temples during the early Christianisation of Chartres. The northern part of the excavated complex had already been consolidated and made accessible to the public, creating a focal point for guided visits and the many outreach activities organised by the archaeology service.

At the same time, a research excavation in the nave of the abbey church of Saint-Martin-au-Val revealed the existence of a 6th-century religious building associated with rich burials in stone sarcophagi. These had already been partly excavated by Adolphe Lecoq between 1858 and 1862. The research excavation carried out by the Chartres unit from 2013 to 2017, with two more campaigns in 2023 and 2024, identified 23 sarcophagi with richly furnished graves belonging to a local elite. The historical and archaeological data showed clear evidence of embalming and cosmetic treatment designed to preserve the outwards appearance of the deceased, and there is strong reason to believe that these individuals may have belonged to the families of the first bishops of Chartres. It should be noted that the later abbey church was used by the medieval bishops for a prayer vigil on the eve of their consecration in the cathedral. The cultural development project of the cathedral enclosure can therefore be mirrored by that of the site of Saint-Martin-au-Val.

In this way, archaeology is playing a positive role in the creation of a cultural project based on the complementary relations between two monumental architectural and archaeological sites that played a central role in the spiritual, social and political life of both the Roman and medieval cities.

Another aspect of the contribution of archaeology to building a local identity lies in the various outreach activities developed and implemented by a dedicated outreach team within the archaeology service. These activities are conceived with a wide and varied public in mind, and can be divided into three main categories. In the first category, community events and open-days allow the public to participate in guided tours of sites and ongoing excavations, attracting upwards of 4000 people over a weekend. These events are also integrated into national programmes during national and European heritage days, which may go hand in hand with the regular programme of conferences and exhibitions that has helped build up a solid base of regular participants and followers. These generally have a strong local theme and can involve well-known researchers, such as the exhibition and symposium organised in 2022 around the remains of a mammoth discovered at Saint-Prest (Mammouths! Géants de la Vallée de l'Eure, with over 15,000 visitors), or the exhibition in 2021 about the Merovingian period at Chartres, which contained a detailed summary of historical and archaeological research carried out in the region of Chartres (Ô Moyen Âge! Les Mérovingiens en pays chartrains).

A final category concerns a variety of educational activities for pupils from primary to high school level. These include the classes du patrimoine, where heritage-orientated coursework and archaeological excavation are accompanied by site visits or school trips to heritage sites. Over 280 such classes were organised between 2018 and 2023. Outside the school environment, children can be introduced to archaeology in general via thematic workshops such as 'Learning to love Latin', 'surviving prehistory' or 'apprentice archaeologist'. Recently, these activities have been extended to districts outside the town centre, to reach under-privileged populations who are less likely to visit the city's museums and monuments. In all the above cases, the focus is on the local heritage with which the public is more likely to identify.

Overall, archaeology is just one component of a wider legal and regulatory framework that aims to preserve the finite resource that is the built and buried heritage. As such, it has a fairly limited influence on the policies that affect the changing face of the urban environments of tomorrow. It does, however, play a vital role in the conception and implementation of cultural development projects that give historical depth and meaning to the urban community, as well as a constant source of new data for the scientific community. The economic benefit of having a permanent archaeological excavation and research unit based in the town is difficult to quantify, as direct costs are far easier to quantify than any indirect benefits. However, there is an underlying understanding by all the stakeholders concerned that the cost of maintaining a strong archaeological activity is, in the long term, much lower than not doing so. In this light, archaeology has become an undeniable value rather than a simple cost. However, this acceptance is always dependant on strong political will, which means that the state and regional organisations must continue to ensure that the services rendered to the public maintain a high level of quality and visibility. Whatever the outcome of the current uncertain social and economic situation in France, the different archaeological actors will continue to adapt to meet the changing demands placed on them.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.