Cite this as: Dubisch, A. 2025 Lübeck's Founding Quarter: Urban Development at an Authentic Site, Internet Archaeology 70. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.70.15

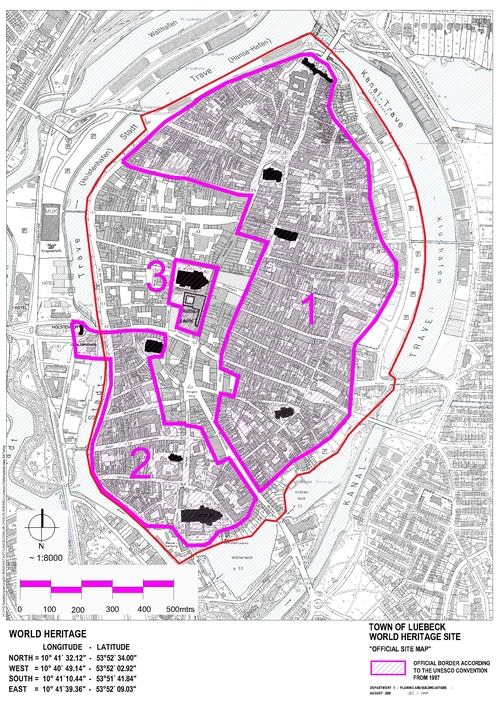

Lübeck is one of the best-researched cities in Germany, with over 1000 archaeological sites. The strategic geographical positioning of the city, situated along the rivers Trave and Wakenitz, played a pivotal role in fostering its development as a prominent Baltic port. This advantageous location facilitated the rapid ascent of the city to be a major centre of influence in northern Europe during the Middle Ages, particularly as the leading city of the Hanse, a powerful commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns. Lübeck's city hill, formerly a peninsula, today has the shape of a north–south oriented oval, extending around 2000 × 1000 m. The old town has been surrounded by water since 1900 and is now an island accessible by five bridges (Figure 1). At the time of the Christian Saxon and Westphalian colonisation, later called Low German, the city hill looked different; both the shape and the current level ratios are the result of intensive settlement over the last 850 years. The architectural heritage, including its iconic Gothic brick structures, reflects the city's rich history and its importance as a medieval trading hub.

Since 1987, the preserved areas of Lübeck's old town, with over 1000 listed cultural monuments, have been a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site (Figure 2). This heritage encompasses not only the aboveground preserved brick buildings, but also the archaeological monuments beneath the surface (World Heritage List 1987). As part of the ongoing attribute mapping process, the management plan for the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Hanse City of Lübeck is currently being updated and is expected to be finalised soon. Understanding the outstanding universal value and its attributes is fundamental to its protection and management, and identifying these attributes and their associated values helps us to understand the World Heritage Site and its surroundings better.

Lübeck's archaeological significance is highlighted by the inclusion of attributes such as underground cellars, foundations, firewalls and cemeteries. A particularly notable development is the addition to the UNESCO listing that recommends that archaeological exploration beneath Lübeck's historic city continue, even in areas not on the World Heritage List. The committee has also requested to be kept informed of progress. Moreover, the entire old town island has been an excavation protection area since 1992, meaning that any ground interventions require authorisation and must be accompanied by archaeological excavations (Figure 2) (LVO 1992). These regulations demand a responsible approach to urban development and construction projects that impact the underground cultural heritage. In a historically significant city like Lübeck, this responsibility is crucial and affects all stakeholders, from developers and city administrators, to local archaeologists. This responsibility influences planning and decision-making processes in urban development, and is also reflected in the communication and interpretation of the World Heritage Site.

As we delve into the archaeological richness of Lübeck's urban city origins, it is crucial to recognise how these layers of history trace back to the city's formative years. Since the early days of Lübeck's first mercantile traders along the riverbank around AD 1100, archaeology has focused extensively on the development of settlements and the founding phase of the Hanse city (Schneider 2019). This leads directly to the significant area: the nucleus of the Low German merchants, the so-called Founding Quarter from which the later Hanse city emerged.

The Founding Quarter of Lübeck is centrally located in the city centre, between the former Hanseatic port on the River Trave and the market square, flanked by the town hall and St Mary's Church (Figure 1). The quarter is situated within this historic area, which is circumscribed by three large streets connected by smaller intersecting ones. This planned grid, established from the outset, remains largely intact. Outside this grid, some impressive buildings still define the framework of the quarter, such as the Romanesque two-storey hall at the port, and the Gothic merchant church next to the town hall. The strategic layout and architectural prominence of Lübeck's Founding Quarter reflect its significance as a major trading hub in medieval times. The urban city's origins date back to 1143, when it was established by Count Adolf II of Schauenburg. This deliberate and carefully planned development aimed to leverage Lübeck's position along key trade routes, which contributed to its growth and prominence within the Hanse. The layout of the Founding Quarter has been largely unchanged since the 13th and 14th centuries, and is still clearly recognisable today. The seven church towers that define Lübeck's skyline are particularly prominent, with St Mary's Church standing out because of its impressive size and historical significance. It is renowned as the church of the townsfolk, merchants and council, and it features the world's highest brick vault.

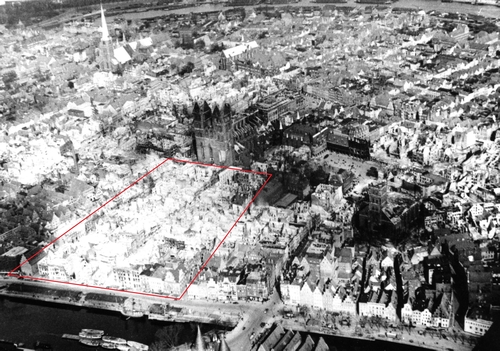

However, the fate of this historic district, like that of many European cities, was profoundly altered during the upheavals of the Second World War. Over night on 28–29th March 1942, the city was hit by the greatest catastrophe to befall it in recent times: Lübeck was the target of the Allies' first area bombing raid. A fifth of the old town was flattened, over 300 people died, and 15,000 people were made homeless. St Mary's Church, St Peter's and the cathedral all burnt down, as did the war cabinet in the town hall and many valuable townhouses (Figures 3 and 4).

After the devastation of the Second World War, Lübeck faced the challenging task of reconstruction. Despite the severe damage, the city made substantial efforts to preserve and restore its historic structures, a testament to its resilience and dedication to maintaining its cultural heritage. Lübeck also fared better compared with other towns. Thanks to the initiative of Eric M. Warburg, a banker from Hamburg, and Carl Jacob Burckhardt, later president of the Red Cross, Lübeck was made the transit point for relief packages being sent to Allied prisoners of war. This meant the city centre was spared from further attacks. Today, the Founding Quarter of Lübeck stands as a remarkable example of medieval urban planning and historical preservation. It continues to attract scholars, tourists and heritage enthusiasts, reflecting Lübeck's enduring legacy as a significant historical and cultural centre.

In the post-war period, no consideration could be given to the historically evolved cityscape. There was a great need for housing and infrastructure, so the city planners made a fatal decision for this neighbourhood: by clearing all the ruins down to the foundation walls, large open spaces were created on which two large school buildings and new apartment blocks were erected (Figure 5).

At the same time, roads were widened to allow more traffic into the town, measures that were urgently needed at the time. However, from 1987, with the inclusion of large parts of Lübeck's old town in the UNESCO World Heritage List, a rethink began in the minds of both the citizens of Lübeck and the responsible authorities. There were repeated calls for restructuring, especially of the Founding Quarter, in the sense of critical urban regeneration. The go-ahead for this was not given until 2009 but, thanks to the German government, it was possible to finance the relocation of the two schools, the demolition of the buildings, and the extensive archaeological excavations required for a new development.

With the demolition of the buildings and the subsequent major excavation, a new chapter was opened for the Founding Quarter. From 2009 to 2016, archaeological investigations were conducted on nearly 50 historical plots, covering a contiguous area of over 10,000 m2 (Figure 6). Here, in what is now archaeologically confirmed as the oldest quarter of the Hanse city of Lübeck, the remnants of an exceptionally preserved urban development were discovered, offering insights into all aspects of urban life. The area encompasses the interior blocks between three major streets, representing a meticulously planned network of pathways from the outset. During the excavation, 164 wooden structures from the 12th and 13th centuries, over 80 brick buildings from the 13th–16th centuries, more than 100 sewers/cess pits, 20 wells, 4 complete streets (including water pipes, ditches, etc.), and copious amounts of material, which was previously scarcely considered, were unearthed. This wealth of archaeological findings plays a crucial, identity-shaping role in both the existing and future planning and development of this neighbourhood.

The preliminary analyses of the large-scale excavation reflect the long history of trade and settlement in the district, from Lübeck's initial colonisation by the earliest settlers to its destruction during the Second World War.

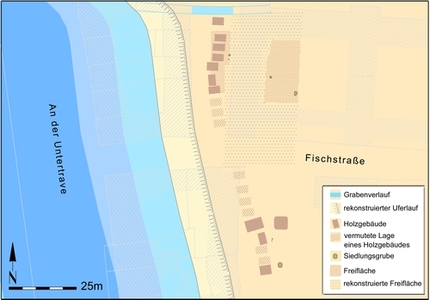

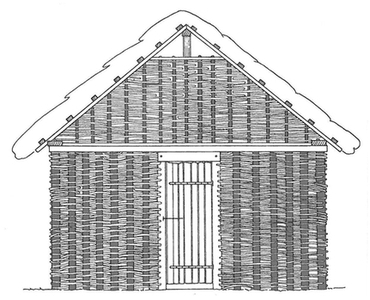

The traders' settlement on the riverbank comprised a series of small, wattle huts, each covering approximately 12 m², positioned closely together where the Gerade Querstraße is today (Figure 7). Their gable walls faced the River Trave and bordered a large, open area extending eastwards. This space may have functioned as an early marketplace or a similar venue for trade.

It is probable that the early inhabitants primarily crafted items from bone and antler, as evidenced by the discovery of small saws, numerous bone combs, and clasps for small boxes. Radiocarbon dating and other archaeological methods have dated this settlement to around or after 1100 (more than a generation before Lübeck was founded). The settlement was established on a plateau-like terrace, which served as a berth for ships. This location can still be identified today. By examining the courtyard between Fischstraße and Alfstraße, one can clearly observe the existing elevation difference, although the original ground levels have been raised over time. This may well be the port described by Helmold von Bosau, which was seen by Adolph II, Count of Schauenburg, when he founded Lübeck in 1143 (Helmolds Slavenchronik).

After numerous battles, political entanglements, and diplomatic negotiations, Duke Henry the Lion of Saxony acquired the former territory of the Slavic king of the same name during the 'German' eastwards expansion. He granted this area, which is now East Holstein, as a fief to Count Adolf II of Schauenburg. In 1143, Count Adolf II founded a new city on the hill of Bucu, located about 6 km upstream from the River Trave. Given the prominence and economic significance of the Slavic stronghold Liubice, he named his new city Liubice as well, which later evolved into Lübeck. Helmold von Bosau recounts in his late 12th-century Slavic Chronicle (Helmolds Slavenchronik) how the count attracted numerous settlers from regions such as Flanders, Holland, Utrecht, Westphalia and Frisia, inviting them to bring their families and claim the promised fertile lands. According to Helmold, the settlers journeyed with their families and belongings to Count Adolf in Wagria, to take possession of the land. Upon arriving at a place called Bukow, the count found an abandoned fortress built by the Slavic prince Kruto, an enemy of God. This fortress was situated on a large peninsula between the rivers Trave and Wakenitz. Noticing the suitability of the location, with its excellent port and stable land extending beyond the fortress's ramparts, the count began constructing the city and named it Lübeck, reflecting its proximity to the old port and the primary settlement once established by Duke Henry. One of the oldest urban planning activities to be discovered by archaeologists was the separation of public and private land, i.e. roads and plots of land, by means of ditches and fences (Figure 8).

Around 1158, following intense disputes with Adolf II, Count of Schauenburg, Duke Henry the Lion of Saxony took control of the town and began its further expansion. He granted special privileges to merchants, which facilitated trade with Gotland and other Baltic towns. This boost to overseas trade, which had been ongoing, significantly enriched the town and its residents. The economic prosperity sparked a major construction boom in the Founding Quarter. By the late 12th century, the area likely resembled a large building site, similar to today, though it was dominated by timber structures. The surviving remnants from Henry's era are primarily the substantial, heavy wooden cellars that have endured for centuries (Figure 9). These cellars were essential for storing and keeping large quantities of goods available for resale. Typically part of a larger building, the wooden cellars were accessed via ramps or brick stairs. The largest ones measured up to 10m in length and 7m in width. Some have been so well preserved that complete rooms, exceeding 2m in height, are still visible.

A life-sized replica of one of these impressive timber cellars was constructed by the Youth Monument Preservation Team in Lübeck as part of the Year of Cultural Heritage. Both the replica and the original cellar could be viewed at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin during a significant archaeology exhibition (see section 3 and Figure 14).

In 1201, Lübeck entered a crucial phase of its development, with the beginning of a quarter-century under the rule of the Danish king Waldemar II. This era of peace led to significant economic growth, as evidenced by the expansion of the settlement. Lübeck's built-up area increased by approximately 50%, through the reclamation of lower lying regions that had previously been periodically or permanently submerged, but were now utilised for construction.

In 1217, King Waldemar II commissioned the construction of a brick city wall encircling the entire peninsula. The port was also redesigned: a new quay wall was built, allowing ships with a draught of up to 2m to dock. The first mention of the Holsten bridge dates back to 1216, when it split the port into a northern section for long-distance trade and a southern inland port. The marketplace was modified, and the town hall that stands today was constructed between 1230 and 1240. Economic growth was also evident in the Founding Quarter, where the first entirely brick townhouses were built. This period saw the construction of tower-like buildings known as 'Steinwerke', and impressive multi-storey halls, with floor areas reaching up to 280 m² (Figure 10). Some remnants of these structures were uncovered during the excavations, while others, such as those at Alfstraße 38, still stand. During this time, Lübeck also focused on strengthening its political and economic power, ultimately leading to its emancipation from Danish control. The Danish king was decisively defeated at the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227.

In the mid-12th century, a group of Low German merchants united with the goal of safeguarding shipping and representing their economic interests collectively, especially abroad. By the late 13th century, this 'merchants' Hanse' had evolved into the 'town Hanse'. Representatives from Hanseatic towns gathered at assemblies known as 'Hansetage' to discuss relations between merchants, towns and trading partners internationally. From the 14th to the 16th centuries, around 200 Hanse towns were recorded, stretching from the North Sea in what is now the Netherlands, through the northern Rhineland, to Sweden and the present-day Baltic states. The Hanse trading network extended even further, reaching France, southern Germany, the Mediterranean and Asia. It had trading posts, known as 'Kontore', in England, Sweden the Baltic states and Russia. Lübeck was the leading centre of the Hanse, from its inception until the final Hansetag in 1669. Trade included building materials such as timber and stone, along with pelts, hides, leather and cloth. Foodstuffs like fish, meat, spirits, spices and salts were also exchanged. Everyday items made of metal, ceramic and glass were part of this international trade, and the scale of transport during this period was unprecedented. The construction industry was innovative, introducing the characteristic Lübeck merchant's townhouse, featuring high halls and attic floors that provided ample space for storing the merchandise being handled.

Many of these medieval houses still stand today, often behind more recent façades that have been adapted to changing architectural styles (Figure 11). Numerous cellars from these townhouses were excavated in the Founding Quarter, and some have been preserved and integrated into new buildings on their original sites.

In addition to the findings and discoveries concerning settlement development, new interdisciplinary approaches to archaeoparasitology, palaeopathology and anthropology have provided fresh insights into the trade and settlement history of Lübeck (Rieger 2022). For instance, in collaboration with the University of Oxford, UK, such approaches have yielded insights into the living conditions and dietary habits of merchants as part of medieval society, offering hitherto unknown perspectives in a highly diverse field of research.

During the excavation work in Lübeck's Founding Quarter, public relations played a crucial role in ensuring that the findings were accessible and engaging for a broad audience. The excavation sites were open to the public during daily visiting hours, allowing people to witness the ongoing archaeological efforts firsthand. In addition to this, a series of guided tours, lectures and events was organised over the years, which further enhanced public engagement and awareness of the historical significance of the site (Figure 12).

An integral part of the public outreach strategy was the establishment of an information point near the excavation sites. This exhibition space provided visitors with self-explanatory displays offering in-depth information about the past and future of Lübeck's Founding Quarter, showcasing selected original finds from the excavations. A unique location was chosen for this purpose: in 2014, the Ulrich Gabler Foundation completed a new building project that incorporated the 1986 discovery of a 13th-century brick cellar (Figure 13). This cellar, uncovered during earlier archaeological excavations, became a central feature of the building. The Ulrich Gabler Foundation's building, located at the corner of Schüsselbuden and Alfstraße, was developed to serve multiple purposes, including facilities for people with disabilities, office spaces and a café. The historical brick cellar, measuring 18.5 × 9.5 m, was carefully integrated into the modern structure. The architects faced the challenge of preserving the cellar's ancient masonry while making it visible and accessible from both inside the building and the street. The solution involved minimising load-bearing pillars to create an open-plan room that highlighted the 800-year-old cellar's dimensions. This space now houses Café Ulrich's, operated by the Vorwerker Diakonie as an inclusive venue where people with and without disabilities can meet. The café not only serves as a historical showcase but also as a hub for ongoing cultural activities. It provides an authentic setting for future thematic tours, events and other educational initiatives related to Lübeck's medieval history. By blending modern inclusivity with historical preservation, the Ulrich Gabler Foundation has created a space where the public can engage with Lübeck's rich heritage in a meaningful and accessible way.

A standout feature of the public relations efforts was the reconstruction of a medieval wooden cellar, which offered a tangible experience of historical craftsmanship (Figure 14). Supported by Lübeck's Archaeology Service, the Youth Monument Preservation Team undertook the construction of this life-sized replica in early 2017. The timber, sourced from Lübeck's municipal forest, was shaped into the sill plates, posts and wall boards of the cellar. The construction was completed as part of the live exhibition 'Restless Times: Archaeology in Germany' at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin from 2018 to 2019. Visitors to the exhibition were able to interact with the reconstruction process, learning about medieval carpentry techniques and the historical context of the Founding Quarter.

Overall, Lübeck's Archaeology Service contributed significantly to the 'Restless Times' exhibition, which highlighted the interconnectedness of European cultural history (Rieger and Jahnke 2018). The Service presented key findings from the Founding Quarter, focusing on the themes of innovation and standardisation in medieval trade and exchange. A major exhibit featured elements of the 12th-century timber cellar, alongside everyday artefacts from Lübeck's Hanseatic period, illustrating the city's pivotal role in the economic and cultural networks of medieval Europe.

Through these diverse and comprehensive public relations initiatives, the excavation project in Lübeck's Founding Quarter successfully bridged the gap between past and present, offering the public a dynamic and immersive experience of the city's rich historical legacy.

Following such a significant excavation and extensive public engagement efforts, the impact extends beyond merely accumulating scientific knowledge captured in scholarly volumes. The true essence of these projects lies in their broader contributions to urban development. The archaeology work is not simply about uncovering the past but also about actively shaping the future of the neighbourhood.

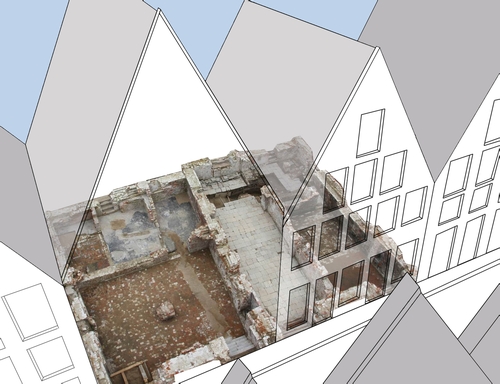

Following the relocation of the schools to other sites and the subsequent archaeological excavation work, it was possible to rebuild the Founding Quarter in a critical reconstruction of the urban structure. This undertaking would not have been possible without federal government funding for both the demolition and the dig, which was provided by the investment programme 'National UNESCO World Heritage Sites'. By 2020, most of the houses on the c.10,000 m² site had been built (Figure 15). Their mixed use will reflect contemporary urban life and so revitalise the neighbourhood. Housing will be combined with offices and small shops, as well as cafés, restaurants and cultural spaces. The concept for the new buildings follows the lines of the old, but the houses are not simple copies of the former architecture. Varied styles of buildings will enliven the streetscape, but their adherence to the former planning structures will also provide a glimpse of the past.

The new Founding Quarter is intended to offer a space for different lifestyle and housing options, and at the same time to be a place of cultural and social diversity. Selected plots have therefore been explicitly reserved for families with children, multi-generation housing and commonhold houses, while on other plots apartments will be built to let or for owner-occupancy.

Archaeology was involved at an early stage in the development of the neighbourhood. In numerous workshops and so-called 'foundation workshops', politicians, authorities, specialist planners, architects and the citizens of Lübeck were involved in the process of urban planning and subsequent design. In addition to the restoration of the historic plot structure, the developers showed great interest in the reuse of the historic building materials that had been removed during the archaeological excavations and put into storage. Materials such as bricks and fieldstones were reused by the architects in the new buildings as flooring or similar. Additionally, it was decided that five stone cellars would be preserved. Beneath the floors of these cellars, the untouched wooden cellars from the 12th century remain in situ. To incorporate these ground monuments into the redesign of the neighbourhood, and to preserve them, one-time agreements were made with the property owners. Unfortunately, not all the plots have been built on yet, mostly because material and construction costs have gone up in recent years. Consequently, there are currently still a few plots that have not been developed, but the goal is to build on the remaining spaces as quickly as possible.

In Lübeck, as in many other cities, archaeology has made significant progress in recent years, finding more creative ways to be sustainably and engagingly presented to the public. However, there are still challenges to overcome to realise its full potential (Schneider 2021). Typically, only isolated features, such as remnants of walls, transparent glass floors, guided tours or museum exhibits, provide glimpses into the past. A comprehensive, long-term presentation following extensive excavations, such as those in the Gründungsviertel, has been lacking. Over the years, smaller scale efforts have been made to make Lübeck's archaeology visible, through exhibitions in bookstores, lectures, events and museum displays. Notably, the European Hansemuseum in Lübeck preserves a section of a prior excavation as an introduction to the history of the Hanse (Figure 16). During the dig a decision was taken not to continue the excavations in one area, but to seal it off. The layers of earth and remains of walls have instead been conserved and integrated into the new building for the European Hansemuseum, and so visitors can now walk through a unique sample of the dig itself, where they can discover many relics from the historic urban layers. A small team of archaeologists, working closely with the restorers, prepared a section of the dig for presentation. This is one of the rare attempts in Germany not only to conserve individual finds or wall fragments, but entire layers of earth. The tour of the museum begins in a room kept at a constant 15°C, where individual features of the archaeological dig and traces of the city's history from the 9th to the 21st centuries are visible. However, Lübeck's urban archaeology still lacks a dedicated museum.

In the coming years, efforts will be made to make archaeology in Lübeck even more accessible and enjoyable for a broader audience. To achieve this, the Archaeology Service is currently developing an overarching concept that will incorporate the existing interpretative work from the Founding Quarter. Starting soon, with trial stations, this initiative intends to provide free access to significant archaeological sites across all four districts for both locals and tourists. The goal is to create a profound connection between people and Lübeck's history by using creative communication methods, including visual, interactive and gamified experiences. Close collaboration with schools, cultural stakeholders, businesses and municipal entities will be essential to the project's success, and continuous monitoring of the project's long-term success will guide necessary improvements. These measures aim to make Lübeck's archaeological treasures accessible to a wider audience and to strengthen awareness of the city's rich past.

As part of this concept, the test stations will be implemented and monitored, serving as innovative platforms to showcase Lübeck's archaeological and historical treasures. One example, currently in the planning phase, involves a project developed in collaboration with the property owners. This project focuses on preserving and integrating historic brick cellars located at Fischstraße 9, 11, 24, 26, and 28 into new buildings (Figure 17). These cellars, which embody various architectural designs and narrate diverse stories, illustrate the evolution of brick architecture in Lübeck. Their preservation is crucial to ensure their unique archaeological and architectural characteristics can be appreciated by future generations.

Construction activities on the buildings above these cellars must adhere to strict guidelines to prevent damage to the historic masonry, following the best conservation practices. This effort includes the conservation of the five historic cellars and their associated archaeological substance within the new constructions. Furthermore, the initiative guarantees public access to all five cellars during specified hours, ensuring their preservation through legal documentation. Substantial financial assistance for the builders is being provided by the Lübecker Possehl Foundation.

As part of the operational concept, the public accessibility of the preserved cellars is secured through a clause in the purchase agreements with the builders. Additionally, there are plans to record regular public access in the Lübeck land registry to ensure that the operational concept remains valid in case of future property transfers. The Archaeology Service has already sent a declaration of intent to the builders, and all the builders have agreed to cooperate in both individual and group meetings regarding the implementation of the interpretative concept. The organisation of public access will be managed by the Diakonie NordNordOst Lübeck. Diakonie NordNordOst operates at 100 locations in northern Germany, working for children and young people, families, people with disabilities, adults in difficult life situations and senior citizens. Under specific, regulated conditions, i.e. fixed monthly dates and prior registration, interested parties will meet at the Café-Keller of the Ulrich Gabler House (Figure 13). As this location also plays a significant role in the Founding Quarter interpretative concept, it is a suitable starting point, both now and in the future. From here, a tour guide will take visitors through the five cellars, as a cohesive visiting sequence to enhance the educational value of the various installations within the sites.

This approach allows visitors to experience the full diversity of the buildings and the unique interplay of 'modern architecture in historic fabric' that characterises the Founding Quarter. Moreover, this arrangement fosters a vibrant and functional inclusion that supports transparent collaboration and open partnership with both the city and the builders and residents of the new district. The Ulrich Gabler House's extended opening hours on Saturdays, alongside special events like Heritage Days, will ensure public accessibility over weekends as well. The entire interpretative concept will be free of charge for visitors. Funds raised through donations will be invested in enhancing visitor engagement and improving the overall experience, including updated flyers, posters and maintenance of the online presence.

Two of five cellars were opened to the public for the first time in 2024 during the Hanse Culture Festival and World Heritage Day, marking a significant milestone in bringing Lübeck's rich past to life. Such events offer visitors a unique opportunity to explore the architectural and archaeological significance of these ancient spaces. For instance, in the cellar at Fischstraße 11, a collaborative effort with the property owner led to the development and implementation of a striking light show that vividly illuminated the cellar's spectacular history (Figure 18). This installation highlighted its architectural features and the remnants of early 13th-century stonework, emphasising the economic prosperity of the Danish era that the cellar once witnessed.

Meanwhile, another unique project was undertaken in the cellar at Fischstraße 24 to engage visitors further. During excavation, a wooden object was discovered that was three-dimensionally (3D)-scanned and then 3D-printed to create a tangible exhibit (Figure 19). This haptic display exemplifies how modern technology can be used to connect visitors with history in a more personal and immersive way. The replica and the fascinating story behind it will be permanently installed in one of the wall niches in the future, allowing visitors to experience it via a QR code. The artefact is a carved wooden figure of a clergyman found in a cesspit. Standing at just 25 cm, this relatively small object may have once been part of a house altar. Similar figures, often made of wood or pipe clay, were used in Lübeck and other medieval cities to represent saints, alongside other devotional items for private worship. Many such devotional objects and symbols of medieval piety appear to have been discarded at the beginning of the early modern period, particularly during the Reformation. This act of disposal may have symbolised the transition from Catholicism to Lutheranism, reflecting the broader shift in religious beliefs and practices. The discovery of these objects, including the clergyman figure, offers a poignant glimpse into the spiritual life of Lübeck's residents and how it was transformed during this pivotal period in history.

The success of these projects during the Hanse Culture Festival and the Day of Open Monuments highlights the potential of the broader initiative. With the introduction of test stations and the integration of historical cellars into modern buildings, Lübeck's rich cultural heritage will be both preserved and made accessible to a wider audience. This approach not only showcases the city's history but also sets the stage for the exciting possibility of establishing a dedicated archaeology museum in Lübeck. Such a museum could be seamlessly connected to historical 'stations' throughout the city, creating a comprehensive network of sites that offers visitors an immersive and cohesive journey through Lübeck's vibrant cultural past. This vision, supported by innovative urban development and careful planning, promises to enhance public engagement with Lübeck's history and ensure that its heritage is celebrated and preserved for future generations.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.