Cite this as: Gaffney, C., Croucher, K., Bates, C.R., Booker, O., Dunn, R., Evans, A., Ichumbaki, E.B., Moore, J., Ogden, J., Ritchings, J., Simpson, S., Sparrow, T., Walker, A. and Wilson, A.S. 2025 Digital Twins at the City and Town Scale: Europe and Beyond, Internet Archaeology 70. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.70.5

The last decade has seen remarkable digital transformations for archaeology and heritage, with the use of three-dimensional (3D) digital documentation approaches increasingly becoming commonplace. In particular, the development of methods that widen participation and increase access to digital tools have led to valuable community-scale documentation of artefacts, archaeological features and buildings. However, without unified ways of representing such tangible cultural assets, or drawing upon intangible heritage, 3D digital models can easily be divorced from their wider contextual meaning. The Visualising Heritage group at the University of Bradford, UK, has a long tradition in digital documentation: the collection and reproduction of 3D recording for heritage purposes. While early work was relatively small scale, such as geophysical data over specific features, or individual bone elements affected by pathological lesions, as part of the Digitised Diseases project (Wilson 2014), work with collaborators has developed the use of rapid methods for accurate digital documentation of objects, sites, cityscapes and landscapes, reproduced across different heritage settings (see Gaffney et al. 2016a, Gaffney et al. 2016b and Sparrow et al. 2024 for the context of this progression).

The necessity of undertaking this form of digital documentation has been reinforced in recent years by natural disasters and anthropological activities. Our response to these includes approaches that use crowd-sourced and web-scraped imagery based on 'tourist' photographs (Wilson et al. 2022). However, it became apparent early on that, while the outputs were fit for the specific purpose, they often require additional information, such as photographs from less attractive/inaccessible locations, or exact measurements to allow scaling and greater exploitation of the models. Seeing the potential impact of this work in the context of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals has helped to ensure that the value of these models is realised for those most in need. Clear examples of this as part of the Building Resilience Through Heritage (BReaTHe) project is evidenced through work with displaced communities (Evans et al. 2020).

The need to upgrade models derived from web-scraped and crowd-sourced imagery is best illustrated by our case study from Kathmandu, Nepal, as part of the joint Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)/British Academy Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF)-funded work using the Curious Travellers methodology (Coningham et al. 2019; Wilson et al. 2019). Various organisations have developed comprehensive workflows to monitor and record the extent of damage from natural and human-induced disasters through satellite imagery and media reports. While the remote assessment of cultural heritage sites and buildings has the advantage of allowing the monitoring of cultural heritage properties from afar, its main limitation is the reduced level of certainty and accuracy of the assessment. This was particularly true in this early case study of Kathmandu, for which we originally generated models using donated imagery and web-scraped imagery but realised that, to be of value in the post-seismic infrastructure reconstruction, accurate on-the-ground measurements would also be needed. The conclusion was that it is essential to have tools and methods in place on the ground wherever possible: an approach that anticipates the potential for change.

Prior to the comprehensive surveys that are described below as part of Virtual Bradford, the digital twin for Bradford, we honed our data-collecting skills by recording iconic buildings within the City of Bradford Metropolitan District, including the Manor House Museum, Ilkley, and the Richard Dunn Sports Centre, Bradford; historic street frontages, including North Parade; and conservation areas, including Goitside (Moore et al. 2022); as well as heritage normally hidden from sight, including the civic rooms within Bradford's City Hall.

Understanding the process undertaken at Kathmandu and via our local case studies, has helped to define what information is required and made possible using digital documentation. Historic England's guidance understandably focuses on the potential of asset information models as part of 'historic building information modelling (BIM)' for condition monitoring, conservation, repair and maintenance (Hull and Bryan 2019). In contrast, the drivers from local authorities often consider dynamic change through other optics, providing opportunities to refine and adapt the capture process and specifications in terms of the level of detail required in the model. As we describe later, the variety of desired outputs is also hugely important to the methodology that is used.

Inevitably, as the resolution of the model and/or area of coverage increases, so does the amount of data that needs to be processed, stored and disseminated. To create a usable, responsive, consistent model, and ultimately a dynamic 'digital twin' that can be shared easily with others, a level of detail needs to be included in the model specification (after Biljecki et al. 2016). The scale of the pilot work that went into phase 1 of Virtual Bradford (with seed-funding from the European Union (EU) SCORE project) and ultimately our emphasis on using 'Data4Good' across several projects and applications earned us the Queen's Anniversary Prize (2021).

For this article, we focus on three projects that chart the development of our approach to digital twins, representing urban areas of different character. While labelled 'living laboratories', we use the term in a more collaborative manner than is usually assumed; the projects are community-focused and have outcomes that are intended to support place-based needs and assets that are of significant local concern or pride. The variety of challenges in each area, and the outputs required from each project, has seen local outcomes that have far-reaching implications. The assessment of these living laboratories has generated the data for this article.

The primary location was the city of Bradford, which is a post-industrial city with a rich and diverse heritage. It was designated the first United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) City of Film and is one of only five UK cities that includes a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Virtual Bradford core area has a typical post-industrial civic centre comprising shops and offices of a variety of dates. Elements of this layout overly the original medieval streetscape, but were transformed by rapid growth during the industrialisation of the 19th century. There are over 180 listed buildings and three conservation areas within the first phase of Virtual Bradford, concentrated on the city centre bounded by the inner ring road. This includes Grade I listings for the City Hall, Bradford Cathedral and the former Wool Exchange. The Wool Exchange and the wealth of buildings in the Little Germany quarter is indicative of the city's status in the late 19th century as a global centre for the worsted textile industry.

The stimulus for a digital twin of Bradford was a push towards clean growth, with the establishment of the Leeds-City Region Climate Coalition and a Sustainable Development Action Plan [PDF], and the introduction of a clean air zone and other overarching plans driving modelled flood risk and air quality. However, the digital twin provides opportunities for shaping urban planning, architectural design, investment and regeneration, as well as with disaster planning mitigation. In addition, modelling and visualisations provide data-driven decision making and explicit opportunities for public engagement and social inclusion, which result in gains for the creative economy (along with Bradford UK City of Culture in 2025), heritage and tourism, and linking into educational resources.

A significant historic area within the Bradford district is Saltaire. This UNESCO World Heritage Site is a planned village that was developed from the 1850s onwards by the industrialist Sir Titus Salt, and is now part of the larger Bradford district. The village is situated about four miles from the city centre, a location selected by Sir Titus Salt for its communication links (including the Midland Railway, Leeds–Liverpool Canal, and Leeds Turnpike Road), access to water, and land, on which he constructed over 800 dwellings with shops and other amenities. According to Richardson (1976, 111) the 'model' village of Saltaire had an average net housing density of roughly 94 per hectare, which is very high in comparison to modern developments in urban environments. While it is tempting to regard Saltaire as an unchanged and possibly even unchangeable cityscape, because of the protections afforded through listing, conservation area and world heritage status, over 1300 planning applications have been registered with the city planning authority since 1970. This 'urban village' therefore represents living heritage and is a place of renewal and change, albeit in a small, localised way.

The third area of heritage used in this article represents a very different urban character. Through international collaboration we have created a substantive digital twin of the historic core of the coastal city of Bagamoyo in Tanzania. Beyond replication in another country, this afforded the opportunity to consider geographic, fabric and character traits of another contrasting form of townscape heritage. The historic town centre in Bagamoyo lies on the Indian Ocean, linking the interior of Africa with Zanzibar and a wider sea-based trading tradition. Centred on the coastal conservation area, the need for quality digital recording in the town was highlighted by the work of Schmidt and Ichumbaki (2020), who noted a decline in heritage assets in the India Street neighbourhood, where 72 buildings documented in 1908 were reduced to 28 assets in 1968, with only 16 buildings noted in 2001, which by 2013–2014 had decreased to 13 buildings. This is a recorded loss of 82% of the historic buildings over one century (Schmidt and Ichumbaki 2020, 37) and is in stark contrast to the developed tourist centre of Stone Town in Zanzibar.

Drawing upon our experience in Bradford, we adapted our capture process to include a knowledge exchange training element in our research, in partnership with a team from the College of Humanities at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Together we worked on rapid capture and digital asset management, with a focus on exploring the creative potential of digital twins for reuniting and reimagining archaeology and townscape heritage, using the historic city of Bagamoyo as a case study. We explored the potential of digital heritage twins for resilience in support of community-focused documentation, conservation, monitoring and management of archaeology and heritage sites; their value for enriching narratives relating to Bagamoyo's important history and strategic coastal setting; and in stimulating artistic responses to tangible and intangible heritage to reach new audiences. These were achieved through co-creation, education, interpretation and outreach; and exploring new uses for digital heritage assets, working across discipline boundaries with artists and creative practitioners, architects and town planners for regeneration, and in support of tourism and craft industries for economic development, responding to the UN Year of the Creative Economy for Sustainable Development.

The main thrust of the work described here and elsewhere by Visualising Heritage has required increasingly rapid capture methods, including mobile mapping and a scalable approach to 3D digital documentation using both simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM)-based mobile laser scanning, and structure from motion photogrammetry, that transcends traditional heritage outputs. The methods that we describe are the result of significant increases in research capability that have arisen from successful infrastructure funding from Research England, the AHRC via World Class Labs and Capability for Collections programmes, and via internal institutional funding.

Underpinning all of the projects detailed here is a substantive investment in research data storage, upgrading high-performance computing data storage for bioinformatics, visualising heritage and SMART cities, which has resulted in 1.8PB usable storage, with replication, snapshots and the addition of a Dell PowerScale Research Storage system with 1.5PB usable storage across different storage tiers/nodes and a third location (cold storage).

Within this investment in digital capabilities was a refreshed geophysical prospection element and space for immersive visualisation. Collectively, these approaches have led to digital representations of physical objects or systems that can be understood at any scale, from objects to buildings, factories, cities and landscapes.

We present the outputs from enabling work across the Bradford District, with three focal areas: Bradford city centre and Saltaire UNESCO World Heritage Site, UK, and Bagamoyo Stone Town, Tanzania.

City Hall laser scan - Decimated to 5cm spacing by Visualising Heritage on Sketchfab

Enabling work within the Bradford district has taken place through the capture of buildings and creation of contextual narratives for the City Hall (Figure 1a and 1b), Richard Dunn Sports Centre (Figure 2a and 2b), and Ilkley Manor House Museum set alongside the parish church and the location of a Roman fort (Figure 3a and 3b). Each of these models has been utilised as anchor points for heritage interpretation and visitor trails, and some of these assets are embedded into downloadable accessible city heritage guides (https://www.visitbradford.com/things-to-do/bradford-city-centre-heritage-trail-p1765821).

Ilkley Manor House by Visualising Heritage on Sketchfab

Ilkley Church, Roman Fort & Manor House by Visualising Heritage on Sketchfab

Phase 1 of Virtual Bradford received pump-priming via the EU SCORE programme, enabling the development of a level-of-detail 3 (LoD3) model of the city centre. Using the CityGML conceptual model standard from the Open GeoSpatial Consortium, the city centre model coverage has been incorporated into routine use-cases for the local authority's Department of Place. Outputs for the city centre have been developed over the last few years at a time when substantive infrastructure change within the city centre has taken place through government investment via the Transforming Cities Fund, with the addition of a landmark building at One City Park (Figure 4) and relocation of the city markets. Collectively this work highlights the importance of both documenting change within the cityscape and the potential value of incorporating digital infrastructure and architectural assets into the digital twin at the design phase.

Place-based research has a multitude of uses, with our work in Saltaire considering the use of the digital heritage captured as part of phase 2 of Virtual Bradford, with funding from the AHRC place programme (Saltaire: People, Heritage & Place). The digital data captured as part of this project served as a stimulus for educational needs, including as inspiration for art-based observations of heritage and place that collectively link to identity and belonging, and related digital literacy for children at Key Stages 1 and 2 (see the related paper in the Internet Archaeology special issue on heritage and wellbeing, Croucher et al. forthcoming). Digital interpretation for other age groups was developed initially for a trail as part of World Heritage Day events, and consolidated as a heritage trail and legacy resource (Visualising Heritage: a Saltaire Experience) using quick-response (QR) codes around the village, with examples of the artwork produced by children showcased alongside further digital content as part of the Saltaire Arts Trail (Figure 5). Planning engagement needs also saw exploration of the potential of projection-augmented relief models using 3D prints derived from the digital twin data (Priestnall et al. 2012).

An important driver for this work was a recognition that a baseline conservation record was essential for monitoring further fabric change within the historic environment (Figure 6), but that the digital twin could also anchor a place-based snapshot of intangible heritage relating to craft industries (including activities linked to boat building; Ichumbaki et al. 2021), fishing (including activities linked to the fish-processing market, now since demolished), salt production and tourism (Cooper et al. 2022). The outputs from the work have been captured in a form that responded to the UN Year for the Creative Economy, and was intended to link intangible narratives with tangible heritage assets within their contextual natural heritage setting (see Bagamoyo, Reimagining Heritage).

The digital twin case studies described here support a variety of uses within and beyond the communities that inhabit them. The use-cases noted are significant, but do not illustrate the full limits of their use or value.

At their heart, the models have value in planning and regeneration activities at a local level. However, it has also been shown that, in a digital environment, the models can be effectively aligned with a better understanding of, and outcomes for, archaeology and heritage within the planning regime. As outlined, there is a clear acknowledgement that the twins can be drivers for tourism and urban heritage trails. Effectively they act as introductions to significant or iconic monuments, thereby using heritage to draw people into urban centres. Significantly, the elements associated with the creative economy should not be underestimated. These include Bradford's role as UK City of Culture in 2025, and Bagamoyo's creative role regarding craft traditions and hosting of the Bagamoyo Festival, an annual arts and cultural festival by Taasisi ya Sanaa na Utamaduni Bagamoyo (TaSuBa; Bagamoyo College of Arts and Culture). Further recognition of the potential of digital twins for promoting heritage tourism can also be seen with the involvement of the Tanzania Film Board in our fieldwork, which led to a showcase at the Zanzibar International Film Festival (ZIFF). The overarching festival theme for ZIFF in 2023 was 'Finding Identity' and we presented our work as part of a workshop/ panel discussion entitled 'Tangible and Intangible Heritage as Archives for Identity', with lead discussants Elgidius Ichumbaki, Thomas Sparrow, Olivia Booker, Andrew Wilson (see https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=AH%2FW006723%2F1).

It is imperative to understand that the outputs from digital twins are not 'standalone' but require context to imbue greater significance within the navigable models. At one level it is evident that contextualising can be similar to layering map-style information; for instance, the 3D Virtual Bradford model has been combined with other datasets for different use-cases, including Ordnance Survey mapping and Bluesky data for tree cover, each of which can be incorporated with 3D BIM models, such as with the One City Park. The enriched environment provides better metrics on 3D measurements, viewpoints, viewsheds and 'right to light' that both protect and enhance the historic environment of the urban core for the long-term. This approach may be regarded as layering of fact-heavy and tangible information. However, there is also a trajectory that requires nuanced intangible content that is layered onto the model; this forms new and people-focused data assets that require different outputs and frequently speak to a wider audience. It is worth noting that the base model that is used might not have textures baked on, and this acknowledgement underlines the fact that there is often more than one model describing an urban centre. In fact, uncoloured LoD models are often ideal when considering potential artistic uses of a model.

Dissemination of lessons learnt and digital twin potential in place-based research and practice has been included in various local, national and international strategy documents. It is noteworthy that the value of the digital twins in placemaking has been recognised. As a result, the understanding of heritage within the urban context is better understood and planning actions are more accountable.

It is evident that there is a wide variety of potential use-cases, and that different use-cases demand different outputs. Across the three case study locations we have illustrated three applications that have planned widely differing outcomes, and that require different strategies for using the digital data. Each has benefited from the value of a contextualised approach, either in support of data-driven decision making, or to aid interpretation and outreach.

Future developments will see Virtual Bradford evolve from digital model to dynamic digital twin: entirely configurable to predict changes not just to the fabric of the structural assets in the centre of the city, but also to predict possible outcomes that may result from potential changes. These include, but are not limited to, a raft of geographical information system (GIS) type analyses, such as viewsheds and light/ shadow considerations. There are also risk assessments for flooding and air quality linked to pedestrianisation. These will require the input of new data and potentially require computationally intensive simulations outside the model environment. As a result of these dynamic attributes, the Virtual Bradford model(s) needs to be inherently digital, and the delivery is best suited to online platforms.

By way of contrast, the Bagamoyo model requires contextualisation of cultural assets. The digital heritage twin needs to function at different levels by embracing intangible heritage and natural heritage, as well as revealing hidden narratives. The purpose of the work in Bagamoyo is to support community-focused documentation, conservation, monitoring and management of archaeology and heritage sites. From the outset this project wanted to include a richer narrative dataset than the Bradford example. As a result, the project has developed a different delivery that is based around the ESRI ArcGIS StoryMaps Collection. The combination of discrete digital data types provides a more engaging interactive narrative that allows individual inspection of the data derived from the digital twin. The collections that are built up can be themed by location or activity to create a hugely successful way of distributing elements of both fragile historic structures that are embedded into a rapidly changing townscape, and the arts, crafts and stories that enliven the digital twin.

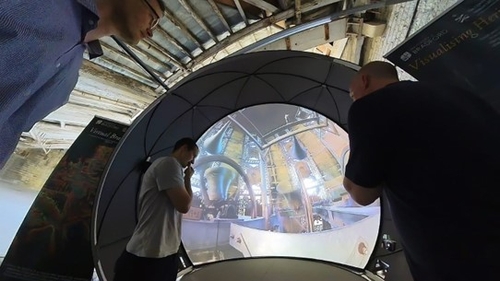

Returning to the urban village of Saltaire, we have combined various delivery modes that have been predicated on storytelling, using a combination of online heritage trails for use by visitors and residents; arts-based outputs showcased using an immersive space sited at the top of Salts Mill as part of the Saltaire Arts Trail in 2023; and the use of projection-augmented relief maps to convey geospatially anchored narratives to illustrate historic zoning in the village and flood risk, as well as identifying planned development.

Throughout each case study, the close cooperation of partners with the local community has provided the focus for place-based narratives that are engaging and important to residents, visitors and planners alike.

We wish to acknowledge the support and assistance of many partners and colleagues, including schools, local community groups, and others across the range of projects.

The funding sources included: (1) the establishment of Virtual Bradford (EU SCORE project) and use of digital twin technologies, AHRC CapCo (AH/V01255X); (2) heritage at risk (AH/L00688X/1; AH/W006723/1); (3) refugee communities (AH/S005951/1; AH/Y003632/1); (4) death, dying and bereavement (AH/M008266/1; AH/V008609/1);(5) art education/place-based identity through observation, digital literacy and artistic expression (AH/W009102/1); and (6) as part of anchoring narratives and intangible heritage to place (AH/Y007409/1; MR/Y022785/1), with additional input from the Erasmus+ programme.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.