Figure 1: IFP2 contents page. HMTL sections to the left, equivalent PDF documents to the right

Historic Environment Manager, Peterborough City Council Archaeology Service. Email: ben.robinson@peterborough.gov.uk

Cite this as: Robinson, B. 2007 Review of Informing the Future of the Past: Guidelines for Historic Environment Records 2nd edition (website), Internet Archaeology 21. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.21.7

Informing the Future of the Past is a website containing working guidelines for Historic Environments Records. http://www.ifp-plus.info

Informing the Future of the Past: Guidelines for Historic Environment Records (second) edition is billed as the 'New and improved manual that empowers HER managers to realise the full potential of their records as information systems for the historic environment'. It is a worthy, and ambitious, declaration. It is also timely, as HER services prepare for another important phase of evolution.

Figure 1: IFP2 contents page. HMTL sections to the left, equivalent PDF documents to the right

Historic Environment Records are the successors of Sites and Monuments Records. The new name reflects an intention to widen the scope of SMR information and services, in anticipation of the new demands that will be placed on them by the forthcoming heritage protection reforms. It also suggests a shift of emphasis from recording 'monuments', to more holistic representations of the historic environment.

Sites and Monuments Records were implemented by Local Authority archaeological services throughout the UK during the 1970s and 1980s. They began as local inventories of archaeological sites and monuments, primarily following the models established by the Ordnance Survey archaeological inventory and by the three national Royal Commissions on historic monuments. Many SMRs began as collections of indexed record cards, which were supported by a series of Ordnance Survey base maps and overlays, on which monument locations, and crop marks etc. were plotted.

They were maintained by local authorities primarily in order to inform the protection of monuments or the ‘rescue’ excavation of sites in the path of planned development. With support from central Government, and its national agencies, they also became pivotal to the national programmes to select the most important examples of monuments, so that they could be designated as Scheduled Monuments, and protected under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979.

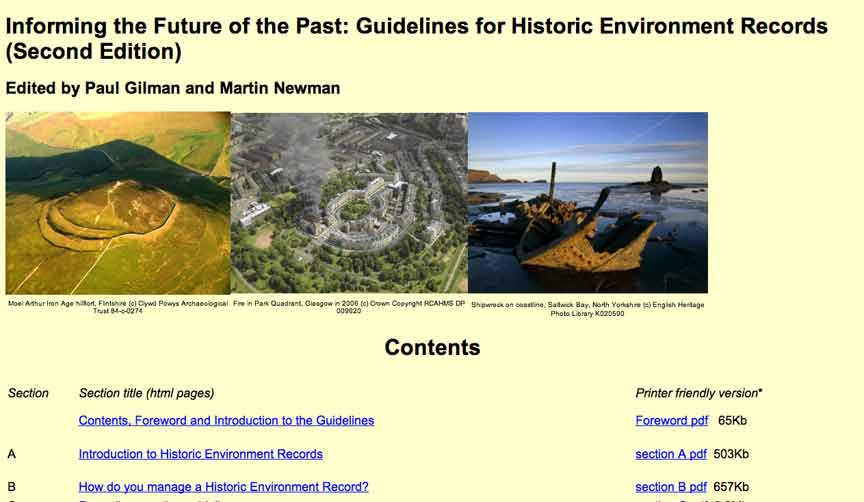

The increasing availability of manageable computers and database software throughout the 1980s and 1990s, along with the considerable efforts of a growing number of voluntary and professional staff, enabled most SMRs to transfer most of their primary text records to digital form, within a variety of database systems. The later 1990s saw the introduction of Geographic Information Systems to manage spatial digital data.

Figure 2: Example of the use of spatial data in the form of three-dimensional modelling in GIS

The collective databases of SMRs (or HERs) are now said to manage well in excess of one million records, but this is far from the whole story. Core Sites and Monument Record entries have always been supported by large and important non-digitised collections of photographs, maps, archives, and large libraries of unpublished 'grey literature' reports, which describe fieldwork and other archaeological interventions. The aggregated local SMR and HER holdings throughout the UK comprise a massive information resource, which is not matched in depth or content by the combined National Monuments Records.

The implementation, growth, and management of SMRs over the last thirty years is one of the great achievements of British archaeology. It is difficult to imagine how archaeology could have achieved its present integrated role within the local development process without the development of SMRs. Indeed, it is hard to imagine how any meaningful conservation of archaeology in the environment could be achieved in the future without strengthened HER services.

Nevertheless, significant issues and problems have arisen in the development of SMRs. Parent local authorities have never had a proper statutory duty to maintain SMR services, and have interpreted responsibilities for their management in bewilderingly variable ways. There has always been a tension between maintaining an SMR service that is adequate for local needs, and one that makes thorough use of compatible Information Technology and data standards, to form part of an integrated national network.

There have also been significant tensions for SMR services between supporting the imperatives of development control and conservation management, and the ambition to encourage greater use of SMR information for general interest, education, and research purposes.

Despite considerable effort over the years, service provisions and information content across the UK are still highly variable as Sites and Monuments Records transform into Historic Environment Records. The huge potential that this expanding historic environment information resource represents is still only partially harnessed.

Guidance notes that encouraged SMRs to conform to common information standards, or to introduce new software, have been issued periodically over the years. It was not until 2000, however, that a guidance document for SMR management was published. Informing the Future of the Past: Guidelines for SMRs, edited by Kate Fernie and Paul Gilman, was designed to fill a gap in general training and professional support that had long been recognised in SMR practice. It was produced as a 'desk manual', and was distributed to each English SMR service in printed form. It is a measure of how dynamic SMR and HER practice has been at the turn of the century, to note that the first major steps to revise completely Informing the Future of the Past were taken less than five years after it was first issued.

Expectations of the need for imminent additions and revisions, and the high cost of distributing a printed and bound document, led to the decision to release the fully revised Informing the Future of the Past (informally known as IFP2) only in digital form, as a Web-accessible document. IFP2 is intended to be more dynamic than its predecessor. The aim is that IFP2 will be able to respond to, and inform, changes in practice (not least those connected with the expected introduction of new heritage legislation and planning guidance) without the need for complete revision and re-issue.

IFP2 has similar basic aims to those of its predecessor. It provides a reference-guide style overview of standards, services, systems, and current issues, and shares examples of best practice across the profession. Crucially, IFP2 also intends to help services to achieve the nationally agreed HER benchmark standards, and to assist the development of true HER services from existing SMRs. This is all highly relevant to an audience of new and existing practitioners, but IFP2 also contains much relevant material for non-practitioners. Elements of IFP2 serve the useful purpose of expressing what HERs actually do (or should do), for the benefit of senior managers and other organisational colleagues, such as conservation officers and planning officers. In fact, anyone who has anything to do with the historic environment and historic environment information (contractors, consultants, teachers, students, researchers, etc.) would benefit from exposure to selected extracts from IFP2.

The production of IFP2 has been an exceptionally collaborative project. It has been supported by English Heritage, Historic Scotland, the Scottish and Welsh Royal Commissions, the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, and the Archaeology Data Service. In addition to the input of a steering committee drawn from these organisations, the meat of the document has been provided by around fifty individual contributors. Many of these are current practitioners, and they represent a good organisational and geographic spread of HER services. And here I have to declare an interest, in that I too contributed a small section.

The breadth of contributors' background, interests, and experience, gives the document a cosmopolitan feel. IFP2 does not simply present an idealised view of a generic HER service provided by a handful of strategic players, but instead complements national standards with views, examples, and opinions, most of which have been drawn from the coal face.

It has taken a long time to compile IFP2, and editing all these contributions has been a mammoth task. The two editors, however, have been able to draw on considerable personal experience. Paul Gilman (of Essex County Council) has for many years managed one of the most distinguished English SMRs/HER services, and provided editorial continuity with the first edition. Martin Newman (of English Heritage) has long been involved in liaison with SMR and HER services.

The variability of the style of IFP2 contributions contrasts with the greater uniformity of the original Informing the Future of the Past, but everything has been welded into a framework of subject areas and sub-sections. There is some overlap in the themes covered by individual contributors, which is partly a consequence of a large number of individuals writing in relative isolation, and partly a natural overlap in some of the subject sections. This generally enriches the content, although there is a slight risk of perceived inconsistency in some areas.

IFP2 has a much wider scope than its predecessor. Apart from extending its coverage to Wales and Scotland, the topics it covers reflect the widening remit of HERs, when compared to the traditional SMR subject areas. IFP2 is at least 30% bigger - over 300 pages compared to 200 pages. How will users navigate through this greatly expanded document?

The designers obviously made a conscious (and welcome) decision to keep things simple. The IFP2 home page provides a link to a contents page. The tabulated contents list provides links to 10 main sections (A-J) and an introductory section. It is immediately obvious that IFP2 is a business-like website. There are no flashy cartoons, no opening 'credits' videos with thumping anthems, and no continuously scrolling headlines. In fact, with the exception of the sponsors' logos on the homepage, and three very good photographs of contrasting aspects of the historic environment on the contents page, there are no fanfares of any kind. Some will see this lack of beautification as a missed opportunity to draw people further into the website. Personally, I think the target audience (most of whom are likely to be fairly frequent users) will be more interested in clarity and ease of navigation.

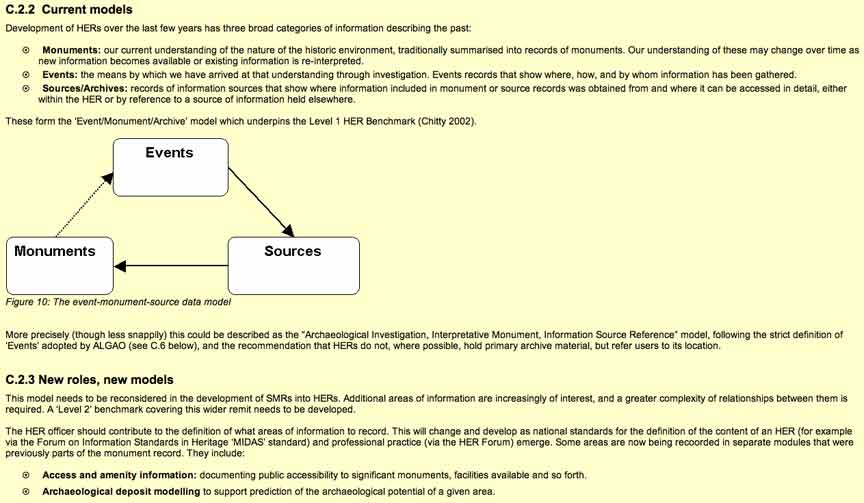

The IFP2 layout is simple and the text is generally a reasonable sized black or blue on pale yellow. Section A provides an 'Introduction to Historic Environment Records', which covers aspects of SMR history, and the current operational context for HER services. Sections B to F comprise management topic areas, such as 'Recording Practice Guidelines' (section C) and 'Geographic Information Systems' (Section E). Sections G to J provide useful ancillary information - a glossary, bibliography, and useful websites and addresses.

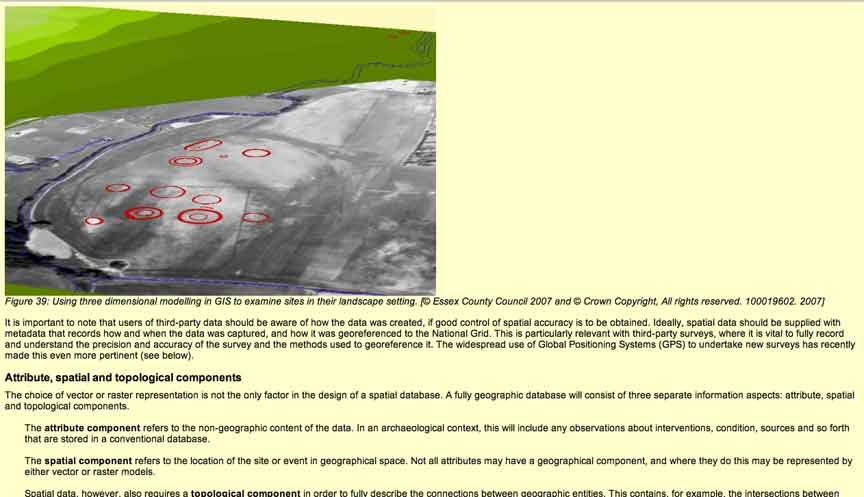

Figure 3: Example of the types of guidance available, showing how to link information held in databases with GIS

Selecting one of the 10 main sections provides a tabulated list of the contents of the sub-sections. So, for example, selecting the link to Section F ('Access to the HER') on the main contents page, produces a contents list of 8 sub-sections (F.1 to F.8). These cover topics such as 'HER information services policy' (section F.1), 'Access and charging policies' (F.4) and 'Developing public access and outreach' (F.7). Selecting one of these headings takes you to the top of the relevant sub-section.

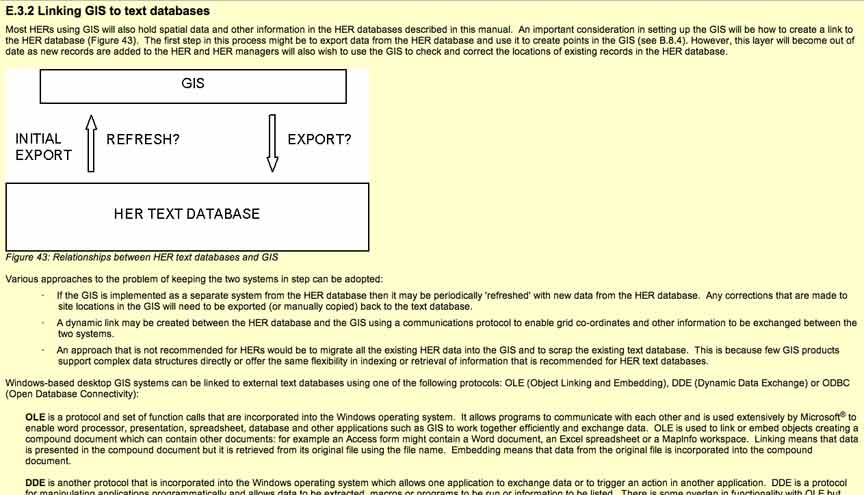

Figure 4: IFP2 provides clear explanations of fundamental and new recording concepts

Some of the sub-sections are quite long and require a lot of scrolling to get through them. It is always difficult to strike a balance in large technical manuals between continuity and readability, and providing direct shortcut access to particular items of information. Inexperienced or infrequent users may wish to read entire sections, without having to select a succession of smaller sections. More frequent and more knowledgeable users may wish to get quickly to a particular phrase, quote, or passage of text, without having to scan through large text sections.

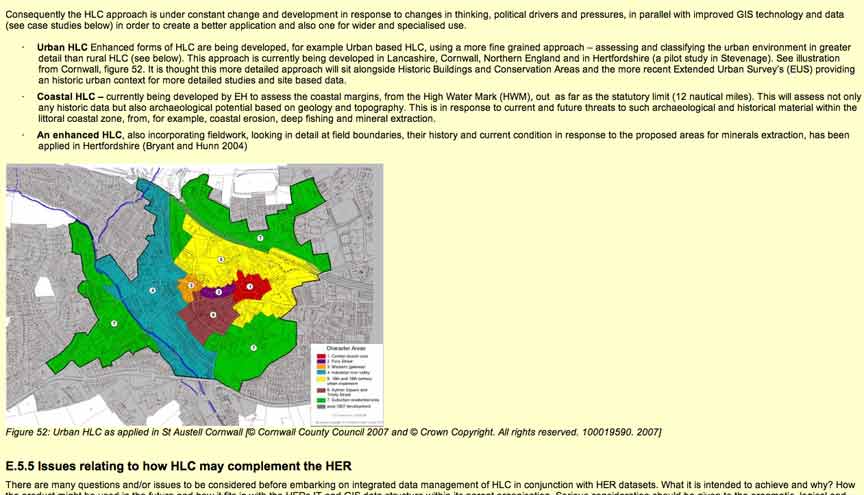

Figure 5: Further example of the types of the guidance available, showing how to expand traditional point and polygon data with Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC) to show time depth

Helpfully, there are other ways to search IFP2. It is possible of course to use your browser's Find function within each text section. But an embedded Google search engine also provides keyword searches of the entire text, and provides links to the top of the relevant text sections. These searches are in no way 'semantic', of course, but nevertheless provide useful alternatives to scanning through text visually.

Hyperlinks to external websites are scattered throughout the text and more links to useful websites are listed in Section I, under various categories. I wonder whether greater use could have been made of links between sub-sections, terms and themes within the document itself. The XML tagging of key terms, for example, could provide links to the glossary or an index, and would enable users to follow certain themes ('standards', 'audience', 'access', 'GIS', 'portable antiquities', etc., etc.) throughout the various sections and case studies of the document. This is probably not entirely necessary presently, after all IFP2 is a manual rather than an encyclopaedia, but it might be worth considering this approach as IFP2 expands.

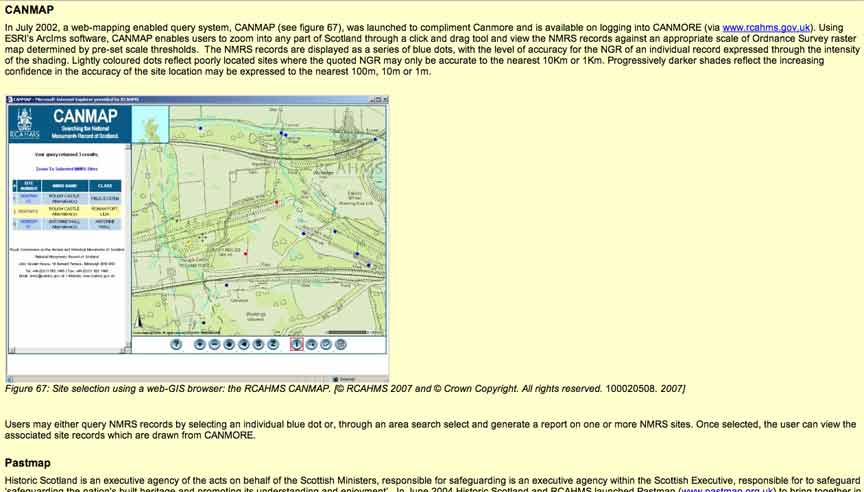

Figure 6: Case studies and examples are complemented by screen shots, diagrams and colour photographs

The ability to expand, of course, is another benefit of publishing IFP2 in digital form. One of the reasons that IFP2 is much larger than the original version is the number of very useful and interesting case studies that are scattered through the sections (for example, section F.7.3 - outreach projects at Somerset, Buckingham, Worcestershire, etc.). These comprise mini essays, which are often illustrated. It is easy to envisage that the number, diversity, and complexity of these will increase with time to such an extent that they will require enhanced indexing arrangements.

In addition to its HTML format, each main section of IFP2 is available to download as a PDF document. Some of these sections are quite large (over 3mb), however, and could pose problems for some users. Cynics may say that the trend towards issuing documentation and manuals only in digital form ultimately saves neither forests nor money. The costs and responsibilities for printing are simply passed directly on to the end-user. Nevertheless, end users do then have a choice whether to print or not to print. In the case of IFP2, they may decide that certain sections are more important to retain in printed form than others.

No major revisions or periodic content reviews of IFP2 have been planned, but incremental changes are envisaged instead. The steering group are keen to have feedback from users and an email link on the contents page has been provided for this purpose. It is still early days for IFP2, and as yet it is not entirely clear how the process of incremental change will be managed and notified in practice. Interestingly, the IFP2 steering group has already collected some information on how the website is used. They have good evidence of its browsing by an international audience and a surprisingly high proportion of American browsers. It should be possible in the future to assess how much attention individual sections have received.

There is a huge amount of useful content here, and all of the relevant current management and information standards issues are covered. I am sure that this new version of IFP2, like the NMR Thesauri and Fish websites, will become a well-used fixture of HER practitioners' Favourites browser settings. Another measure of the success of IFP2 will be the degree to which the wide participation that has characterised its preparation continues into its on-going revision. Obviously, national standards, legislation, etc. will be formed and adopted in various other arenas, and then summarised in IFP2. HER practitioners, however, now have a great vehicle for sharing current examples of best practice, advice about how to interpret and act on new standards and legislation, and case studies that show how emerging technologies can improve their services.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.