Reverting to the enclosed spaces of hillforts, their interiors and raison d'être, it is not unfair to state that little investigation of merit was undertaken in Wales until the necessity of seeking out relatively subtle evidence for timber structures had become overtly recognised and embraced. Earlier efforts have already been castigated here, and it was late in the 1930s before anything of real value was achieved on this front. As is well known, Gerhard Bersu's extensive excavations of 1938-9 at Little Woodbury, soon famed for its record of large roundhouses and other post-built structures (1940), and Mortimer Wheeler's measured campaign of 1934-7 at Maiden Castle (1943 — also recording post-built structures, but less consistent in definition) opened many eyes to the possibilities. Neither was without fault, but they had set new standards in England, deserving to be influential and giving ample incentive for others to emulate their performance — reverberations were soon felt in Wales. It will have been obvious, at least to some, that the character of excavations, as well as that of many excavators, had to change, for such results could be accomplished only by opening sizeable areas, and there was a matching requirement to improve control over the conduct of much of the work done on site, in order that the relevant, and often quite small, features of archaeological interest might be detected. Greater tidiness becomes increasingly apparent in photographs published by many excavators as time progressed.

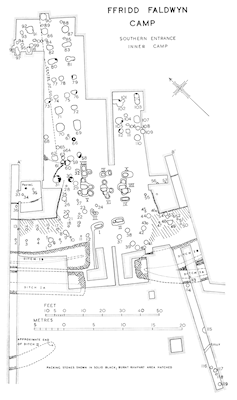

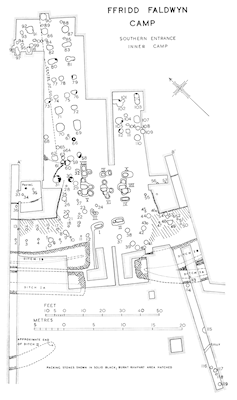

A prime example, and one which is memorable for other reasons besides its extent (including its entrance noticed above), is provided by Ffridd Faldwyn (O'Neil 1942). In 1937-9, an area in excess of 300m², with irregular limits showing it to have accumulated by repeated expansion, was stripped inside the 'Inner Camp' of this multivallate, and clearly multi-period, contour-fort. That area may seem meagre by comparison with the simultaneous, piecemeal, unearthing of some 6200m² at Little Woodbury, but it was extensive by the yardstick of earlier work in Wales. Initially, O'Neil's approach to examining the banks and ditches of Ffridd Faldwyn was no more spacious than those of earlier decades (including some of his own), and the internal stripping, abetted by shallowness of deposits and absence of stratification, started in an 'inconclusive' search for evidence of guard-chambers to accompany the excavated gateways of the Southern Entrance. Eventually, it reached upwards of 25m into the interior, laying bare 'a vast series of holes', many falling into rectilinear patterns, which seem certain to pass beyond the limits of excavation (Figures 12 and 13). These were immediately likened by O'Neil to the drying-racks and granaries postulated at Little Woodbury, and they have acquired enhanced significance because similar rows of close-set four-post and six-post structures have subsequently been uncovered, and more extensively, inside other hillforts (including Moel y Gaer, Rhosesmor — Guilbert 1975b, 205-9, figs 1-2; see below and Moel y Gaer, especially Figures E and H). Recognising the value of recovering 'so much structural evidence', O'Neil declared that his involvement with Ffridd Faldwyn had 'so far only … begun' and that 'continuation of the work, when circumstances permit, is imperative' (1942, 9 and 21) — what a pity that adverse events intervened to prevent the intended resumption, for, had he been able to excavate more expansively, the influence of this place would surely have been writ even larger over hillfort studies in Britain.

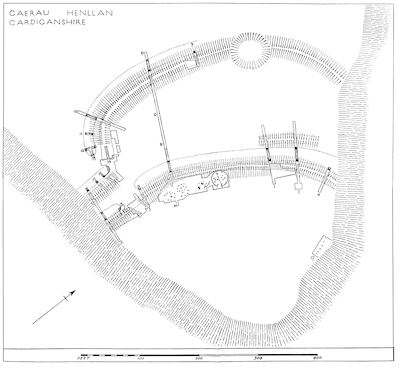

Another early instance of area-stripping, this one prompted by World War II rather than curtailed by it, was undertaken in 1942 inside a multiple-enclosure promontory fort at Caerau, Henllan (Williams 1945). Although again combined with too many narrow cuttings through the earthworks (including 'taking a trench along the crest of the rampart' in search of an 'entrance break', a practice that would seem even more dubious had the bank not already been 'much reduced by ploughing' (Williams 1945, 226, 229)), it was the intersecting of a 'black habitation soil' behind the inner bank in one of those trenches that seems to have motivated progressive uncovering of a consolidated area containing patterns of features quite unlike those seen in the excavation of similar size within Ffridd Faldwyn (above). At Henllan, distinct clusters of postholes, none of them easy to interpret, included at least one well-defined post-built roundhouse, its wall-slot describing a building of almost 9m diameter (Figure 14). It had taken many decades of digging to reach the point where an indubitable roundhouse — what we now know to be a classic 'fossil' of the age of the hillforts — had surfaced inside a hillfort in Wales. At last, adoption of an open-area, one might say open-minded, approach to excavation had facilitated discovery of the ground-plan of a timber roundhouse, relegating feeble presumptions of 'rude huts' into a thing of the past.20

It is befitting to acknowledge respect for the excavators of both Ffridd Faldwyn and Henllan, as the authors of forward-looking projects in the context of hillfort interiors, even though each may have arrived at that position as much by happenstance as by premeditation. True, we may now wish they had excavated yet more widely, for the area opened represents an insignificant proportion of either hillfort, but, in company with grander excavations like Little Woodbury, each gave a strong glimpse of the sort of insights that might accrue through uncovering virtually arbitrary blocks of such sites, and did this far better than others had done in Wales up to their time (plus many of, and since, their time). It might be expected that these results would have become seminal for all investigating Welsh hillforts, because the stark and intriguing difference between the postholes patterns seen at Ffridd Faldwyn and at Henllan surely should have provoked a greater reaction in the post-war years than seems to have been the case.21

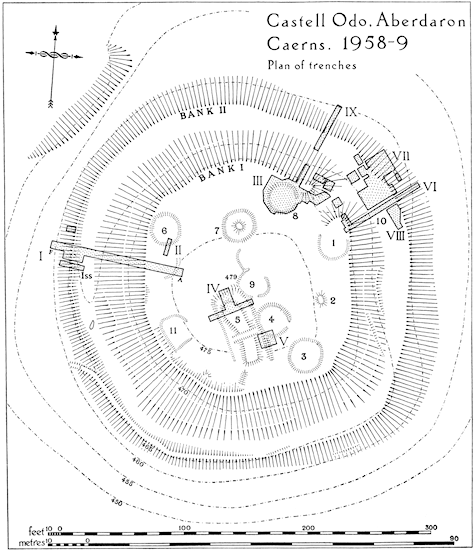

In fact, the lead given by O'Neil and Williams was not generally heeded, though, to be charitable, it may be supposed that this was due partly to financial constraints. Other excavators continued to opt for excessively selective sampling inside hillforts and related enclosures, particularly where surface undulations indicated the presence of barely buried structures. Sites offering opportunities 'to explore economically' proved enticing, as in 1949-50 at Mynydd Bychan, where Savory employed a multiplicity of trenches dispersed widely to test as many as possible of a medley of humps of varied age, initiated as a 'pocket hill-fort' (1954, especially fig. 26). At the opposite end of the country, a comparable example can be found in Alcock's 1958-9 expedition to the little hillfort at Castell Odo, with numerous trenches judiciously set out to tackle a range of its superficial features partially (Figure 15), finding complexity where the remains had 'appeared relatively simple on the surface', and aiming to construct a 'coherent narrative' of stratigraphical and structural development, 'in which the inconsistencies of the evidence are ignored' (1960 — the proposed sequence is summarised in Smith in this issue). It may be thought unfair to emphasise the latter stance, but it does sometimes appear that ingenuity at maximising every seemingly useful shred of the information collected is characteristic of excavations of this tightly confined question-and-answer genre, apt to generate fluent accounts that run an even bigger risk of specious conclusions than do less-contrived strategies conducted through more consolidated and relatively expansive excavations.22

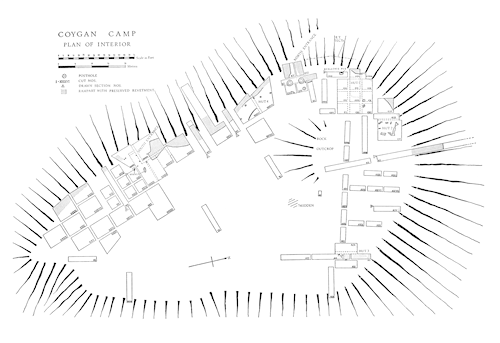

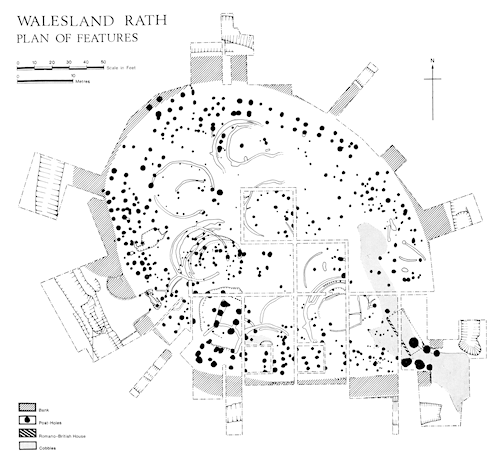

Some three decades after the revelation of serried structures at Ffridd Faldwyn, events in the south-west finally set the tone for a more expansive approach to investigations inside settlement-enclosures, including hillforts, in Wales. Specifically, excavations at two separate places, Coygan Camp and Walesland Rath, can be held to mark a threshold from multiple trenching to large-scale area-stripping, because these occurred in the space of just a few years, each directed by Geoffrey Wainwright. In 1964-5, he examined the interior of Coygan Camp in time-honoured style, with piecemeal trenching, though lacking guidance from obvious surface features (Wainwright 1967; and Figure 16), while 1968 found him uncovering almost all the enclosed area at Walesland Rath (Wainwright 1971; and Figure 17). The contrast could hardly be more striking. At the time, Wainwright recognised of Walesland Rath that 'such an operation is only rarely undertaken in British archaeology' (Wainwright 1971, 48), and today it seems to symbolise the change from a historical to a modern excavation strategy in relation to hillforts, at least regarding their internal spaces. Judging from the incomplete grid of baulks evident in the southern part of Figure 17, it was perhaps the greater density of structural features encountered at Walesland Rath, rather than a superior predetermined strategy, that prompted this metamorphosis, and it is true too that this was a relatively small settlement (at c. 0.25ha, Walesland was scarcely half the size of Coygan), so making full excavation more manageable. Even so, the initiative taken at Walesland Rath represented a breakthrough, such that, by rights, its speedy publication ought to have become equated with an irrevocable turn-about in attitudes to all excavations of related sites in Wales.

As one obvious consequence of that difference in approach, the patchwork of trenches laid out across Coygan Camp has deservedly earned it comparatively little attention in the subsequent literature,23 whereas the practically uninterrupted excavation plan of Walesland Rath, with numerous structures round and rectilinear plain to see, has been reproduced repeatedly in works of synthesis. Even had identifiable structures remained thinly scattered, it is arguable that a more consolidated excavation of Coygan Camp would have provided an end-product more readily intelligible than the fragmentation seen in Figure 16, baring all and thereby allowing the gaps between the structures to emerge as potentially meaningful, in a manner that is effectively denied them by the myriad of baulks.24 In contrast, the overall impression conveyed by the comprehensive plan of Walesland Rath creates an image of how structures were disposed inside one of the many such small enclosed settlements in that corner of Wales. Of course, there is a sense in which that impression is unrefined, inasmuch as it presents a palimpsest from several episodes of building across occupations that spanned the Roman conquest, so that uncertainties are inherent. None the less, the composite Walesland plan possesses sufficient clarity of definition to have permitted a persuasive reinterpretation of some part of the dense distribution of postholes, initially thought likely to include 'peripheral timber ranges', which, in light of similar arrangements recorded elsewhere, are now regarded as numerous four-post and six-post structures (Figure 18).25 Such latitude for reassessment points up one of the ways in which individual settlements subjected to extensive excavation will surely retain relevance as knowledge of settlement forms slowly accumulates, so that the interest and potential of the plan of Walesland Rath is bound to have a greater longevity than could ever be achieved by that of Coygan Camp and similar old-style bitty excavations, which, it should be remembered, remain much in the majority.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.