Cite this as: Zirne, S. 2018 The Relevance of Professional Ethics of Archaeologists in Society, Internet Archaeology 49. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.49.14

The issues surrounding the importance, preservation and protection of archaeological heritage in Latvia became topical with the amendments to the law 'On Protection of Cultural Monuments' in 2013. The amendments to the law were proposed due to the critical situation in the country in relation to the use of metal detectors and the resulting damage to state protected archaeological monuments.

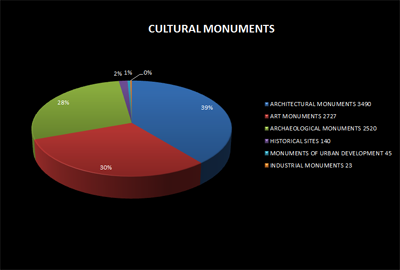

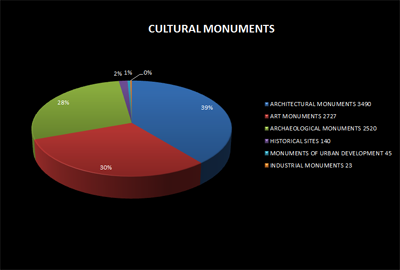

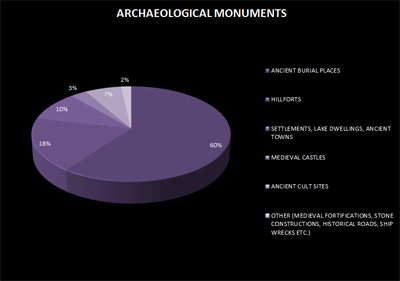

There are 8,945 cultural monuments included on the Republic of Latvia's List of State protected cultural monuments, and 2519 of these are archaeological monuments (data as at 29.09.2017), making them the third largest group of cultural monuments (Figure 1). All preserved and identified archaeological sites are listed, and because a monument in some cases consists of two or three sites forming one united complex (e.g. a hillfort and settlement or a medieval cemetery and church site), the total number of protected archaeological sites is actually higher (approximately 2600) (Šnē 1999, 171-72). The numerically largest group of listed archaeological monuments is made up of ancient burial places — burial-mounds, burial fields and medieval cemeteries (Figure 2). They are more at risk than other groups of monuments due to the high concentration of archaeological finds.

Archaeological monuments in Latvia are usually located in rural areas, in forests, sometimes far away from populated territories. As a result it is difficult to control the preservation of archaeological monuments without broader public engagement and support. A precondition for this is the public perception of the importance of the archaeological heritage.

On 23 January 2013, the amendments to the Law 'On Protection of Cultural Monuments' (Law on Protection of Cultural Monuments 1993) entered into force. They gave rise to substantial changes in the management of archaeological monuments.

According to this law, artefacts found in archaeological sites underground, above ground or under water (dating from 17th century or earlier) belong to the State and will be stored in public (state-accredited) museums to ensure that they are preserved and accessible to the public. According to the law, artefacts are objects created by a conscious human activity: items such as jewellery, weapons, tools, household objects, ceramics, coins found underground, above ground or under water in intact form or fragmented.

Archaeological sites consist of state-protected cultural monuments and newly discovered sites. The amendments of the law define, in a more precise way, the existing notification procedure used for newly discovered objects that can have historical, scientific, artistic or other cultural value. The notification period has been shortened and the State Inspection for Heritage protection should be informed about a find not later than 5 days after the find (formerly 10 days) so as to enable faster assessment of the archaeological importance of the site and to reduce the threat of its destruction.

The law prohibits the removal of artefacts outside of the Republic of Latvia and restricts the use of metal detectors and other devices for the detection of metal objects and material density in cultural monuments and their protection zones. These zones surround cultural monuments and newly-discovered cultural monuments at a distance of 500 metres in rural areas, and in towns at a distance of 100 metres. Any activity within the protection zone, which affects the cultural and historical environment (e.g. construction, artificial modification of terrain, forestry activity, retrieval of such previously unidentified objects from the ground or the water that might have historical, scientific, artistic or other cultural value) must be performed only with the permission from the State Inspection for Heritage Protection. It is prohibited to use devices for the detection of metal objects and material density (e.g. metal detectors) in the protection zone around a cultural monument without the permission of the owner (possessor) of the immovable property (Law on Protection of Cultural Monuments 1993).

The amendments to the law defining the restrictions on the use of metal detectors are focused on the broader engagement of the owners of cultural monuments and on their responsibility for the preservation and protection of archaeological sites located on their property.

Discussions that arose before the amendments to the law, especially on websites, and are still continuing, show that there is a strong public interest in archaeological heritage preservation problems in Latvia. At the same time, they also reflect misconceptions of the work of archaeologists. In many cases this is not flattering for the professional activities of archaeologists and points to a lack of comprehension about archaeological study methods, the process and the results.

At the start of 2016, Latvia had a population of 1,969,000 people. During the period of 2008-2016, archaeological research management licences were issued to 48 people, which, in this context, can be regarded as the total number of specialist archaeologists in the state. Mathematically this means that there is one archaeologist for 41,021 people. Furthermore, it means that any unethical action of the archaeologist can be easily spotted by the society, thus shaping the overall perception of the work of archaeologists. The public is interested in its past, and people are naturally attracted to adventures and discoveries, but who else, if not the archaeologists themselves can introduce society to archaeology?

While acknowledging that comments on the internet are not an objective source for research, they cannot be ignored completely when reflecting on public attitudes. By critically assessing these commentaries, it is possible to identify some problems connected to the professional ethical issues of the work of archaeologists. The main issues are insufficient communication and a lack of information for the public on the goals, discoveries and results of archaeological research.

The most widespread comments are that archaeological antiquities are the main and most significant research subject in archaeology, and that the work of archaeologists is related to jobs in offices without doing any fieldwork. The most frequent type of comments is that it is "better for someone to dig that artefact out than no one..." (http://www.tvnet.lv/zala_zeme/daba/434490-rigas_hes_daugavas_krastus_izraknajusi_melnie_arheologi/). A subsequent comment points towards there being insufficient information about archaeological work: "Can the historians remind us of the major discoveries, expeditions and excavations done in the last 10 years that have resulted in expositions and exhibition halls accessible to the public? So, where are they? Or do they only know how to cry and complain about the lack of money and the wrongdoers".

Latvian society and its moral values have changed from its founding till the present day due to various political and economic circumstances. It has resulted in economic interests often being set as a priority. Consequently, archaeologically significant places are regarded as an obstacle to the realization of economic interests for certain people. Archaeological antiquities are also seen as a means for profit. Notwithstanding the legal framework, the issues surrounding archaeological heritage protection are still complex and difficult to be addressed.

Despite the Code of Practice of the European Association of Archaeologists that states that 'archaeologists will take active steps to inform the general public at all levels of the objectives and methods of archaeology in general and of individual projects in particular, using all the communication techniques at their disposal' (EAA Code of Practice 1997), the communication of archaeologists with the wider public in Latvia has been neglected for a long time. Often it has only consisted of offering a scientific publication as the main outcome of practical activities, while at the same time not providing enough information on the fieldwork, the research methods and the post-excavation process. It has remained an unresolved issue how to explain to the public the process of analysing archaeological data, often taking a long time and requiring careful work that often remains unclear to the general public. Unfortunately, this results in erroneous perceptions about the process of research and the work of archaeologists.

The situation is now changing, and archaeologists' activities are becoming more visible. This is partially connected with changes in the generations of Latvian archaeologists and with the wider technological opportunities that enable social media to publish topical information on archaeological discoveries, research and problems in the field. Meetings between archaeologists and the public are becoming increasingly common in places where excavations are carried out, and in this way local people are informed on major discoveries, thus highlighting the significance of archaeological heritage and the necessity of these studies at the same time.

In Latvia, school programmes do not include archaeology and it is often only presented by enthusiastic teachers. Young people have the opportunity to participate in the Riga Pupils Palace Archaeology and Old Town History hobby group, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2016. Under the guidance of the current hobby group manager, archaeologist I. Kuniga, youngsters between the age of 10-18 can learn the theoretical foundations of archaeology. Each year they can participate in camps where practical activities, including excavations, take place.

During the last few years, participation in archaeological excavations has also become possible for local young people thanks to the activities of the private archaeological company Archeo, founded in 2011, with the support of local municipalities. Alongside the scientific study of archaeological monuments, educational work was also done for younger people and contributed to their understanding of archaeology and history.

Since 2015, the Latvian History Institute of the University of Latvia restored the tradition of holding workshops on archaeology for history teachers. This tradition dates back to the first period of the Latvia's independence before World War II. During the project 'Archaeological excavations and history teacher field workshops', the history teachers had an opportunity to participate in archaeological excavations in a hands-on way, as well as attend a series of lectures on a range of theoretical archaeology subjects.

It is important to choose the right archaeological site for teaching fieldwork. Are there any 'right' or 'wrong' sites? Maybe that doesn't matter? This is an important ethical question. In the Latvia Riga Pupils Palace Archaeology and Old Town History hobby group, the manager selected endangered archaeological monuments for excavations; archaeologists from Archeo trained local pupils at medieval castles (Figure 3) and hillforts (Figure 4); archaeologists of the Latvian History Institute held two field workshops for history teachers at the newly discovered archaeological sites, namely a medieval cemetery and burial ground with cremations, as well as at a state-protected burial ground.

Early in 2015 seven archaeological monuments were destroyed in Latgale, situated in the eastern part of Latvia. Looters had destroyed hundreds of late Iron Age burial mounds and pillaged antiquities from burials (Figure 5). These illegal operations were only possible because the burial mounds were located in forests and far away from populated areas. Criminal procedures have been initiated due to the damage done. News about the destruction was published in print and social media. Unlike the period up until 2013, almost all comments about the ravage that was discovered in 2015 were condemning it (http://www.kasjauns.lv/lv/zinas/187314/latgale-masveida-apgana-senkapus-zaudejumi--miljoniem-eiro-video?news_com=1/) although the majority of condemnations concerned the desecration of graves and less to destroying archaeological monuments.

Alongside critical comments about the destruction of ancient burials, comments were also made on whether anyone even has the right to dig an ancient burial grounds. One of the comments characterising this position was: "…nuzzling in graves, that is the most beloved activity for archaeologists! Leave the dead alone!!!" (http://www.tvnet.lv/zinas/latvija/419951-melnie_arheologi_atkal_aktivizejusies_senvietu_postisana/ )

This gives us reason to consider whether society is ready to accept the fact that archaeologists have a right to excavate burial grounds for scientific research. From a point of professional ethics, archaeologists should reaffirm that the ancient burial grounds are a source of history and that they should treat human remains with respect, ensuring reburial after research has been finished. The issue is unsolved how ethical it is to involve the general public with this particular type of archaeological work. One should also consider whether it would not be more ethical to do practical studies on ancient settlements or other types of archaeological monuments where one does not have to discover and study human remains and instead work with data obtained from studying cultural layers, constructions or other archaeological evidence.

There is no specially developed and legally binding Code of Ethics for archaeologists in Latvia. During the 1990s, the decentralisation process began in the field of archaeology, resulting in the situation where archaeological fieldwork was being done by self-employed archaeologists. Only during the last few years have a few small companies started operations with their work being based on contract archaeology. Thus, archaeologists are acting as private entities and perform fieldwork and communication with the public at their own discretion. They execute their obligations and archaeological research requirements but at different quality levels.

The decision to develop a Code of Ethics for Latvian archaeologists was made during the general meeting of the Latvian Association of Archaeologists in 2014. It should contribute to legal, fair and professional activities of archaeologists, as well as promote the relevance of the archaeological profession in society. A working group was established for drafting the Code of Ethics, which consisted of representatives of various institutions: the Institute of Latvian History at the University of Latvia, the National History Museum of Latvia, Archeo Ltd and the State Inspection for Heritage Protection. The rest of the members of the Latvian Association of Archaeologists received the draft of the code of ethics during the Spring of 2015 with invitations for a wider debate. Unfortunately, the broader discussion has not given rise to much interest among archaeologists.

In the last few years, archaeologists in different countries have developed or reviewed their Codes of Ethics indicating that these are topical issues and that they are connected to the general public's perceptions of archaeological heritage, archaeology and the work of archaeologists. Archaeologists are a numerically small part of society, a society in which archaeological heritage forms the basis for its professional growth. It is a distinct opportunity for an archaeologist to convey the message of its own importance to the rest of society. Formulating ethical values and establishing unified professional, ethical standards could become a significant factor for shaping the perceptions of society. In the long term these would then serve as a basis for increasing the confidence of society in archaeological professionals.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.