Cite this as: Virágos, G. 2018 Dare To Lo(o)se, Internet Archaeology 49. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.49.6

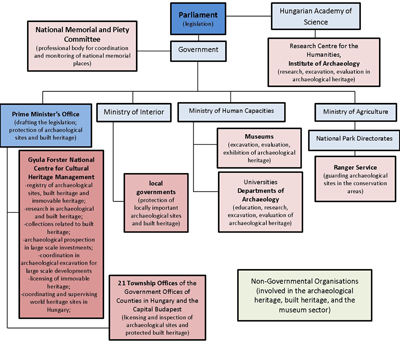

In the first part of this article, I will focus on some major changes in the Hungarian cultural heritage management system. It is barely believable how the model has changed in such a short time. The complexity of the system can be seen in the 2016 structure in Figure 1. Yet this is already not current anymore and further alterations are expected.

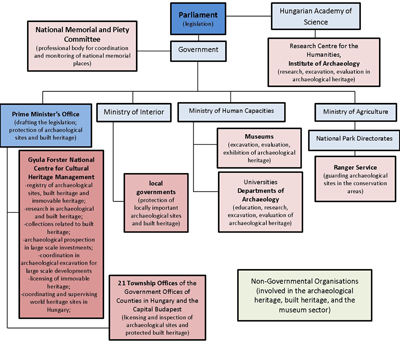

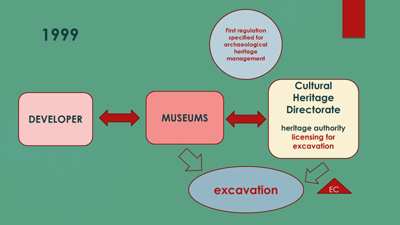

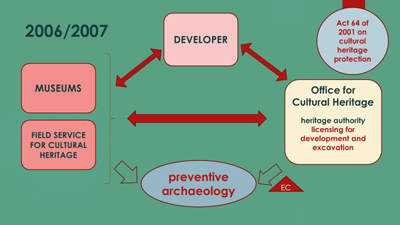

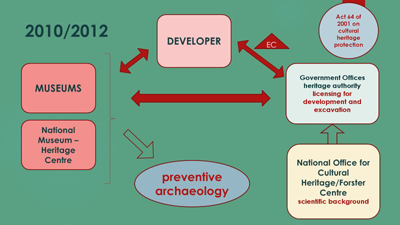

Before and right after the political change in the 1990s, archaeological work in Hungary was based on the structure of county museums, universities and professional research institutions. The licence to excavate was issued by the Excavation Committee (EC). When the administrative system of the country changed, a specialised office was also set up for archaeological heritage management (Cultural Heritage Directorate) in 1999. The EC became part of this institution (Figure 2). Within two years, the new Office for Cultural Heritage became the licencing authority for development-led archaeology as well (Figure 3). This period can be seen as the peak of cultural heritage protection in Hungary: the system was working at its full power. However, the professional organisations were gradually overloaded, focused far too heavily on financial issues (i.e. too much money appeared in preventive archaeology too fast) and they were not really concerned about the needs of developers, who were otherwise the financiers of the whole structure.

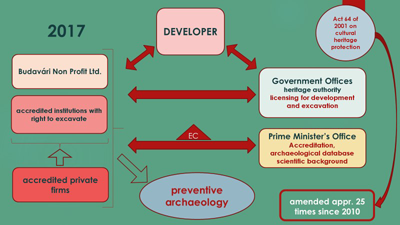

Hiding behind the Hungarian understanding of the Valletta Convention (every single find has to be excavated, and the excavation should be financed by the developers), the archaeologists of the county museums did not partner with developers but simply dictated the conditions. A lobby of investors and representatives of the state (which was the biggest developer itself at the time) gradually started to work against this structure. There were two options: to open up the market for excavation companies or to centralise everything on a national level. Although a third possibility, to eliminate the entire structure, was not a real option at that time, this period (the early 2000s) laid down the foundations for terminating the good reputation of archaeology. The actual decision was to centralise the structure, building up a national infrastructure in addition to the local ones for excavations (Field Service for Cultural Heritage) (Figure 4). Despite its success and importance in managing the never-seen requests for preliminary excavations country-wide, the new political era after 2010 eliminated the structure and started the gradual disintegration of cultural heritage management (Figure 5). The whole professional field became the playground of politicians, giving space for uncontrolled on-site activities despite the legal regulations. The accreditation of private companies was not a success story and the present situation (a few companies cover the whole market and work under the umbrella of county museums) is not advantageous for the archaeological heritage or for the developers (Figure 6). Seemingly, approximately every five years there is a major change in the whole system, so terminating the actual structure this year would not be a surprise. We can also expect something new in a few years again. More precisely, following the patterns of the past, further changes should come in 2022 at the latest.

Putting an investigation of the Hungarian system aside, let's look at the decision-making more generally, as a theoretical framework. Different aspects of the decisions are of interest, and considering the complexity of making decisions, one has to answer several questions.

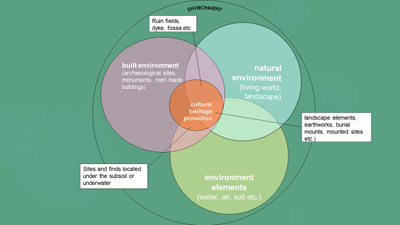

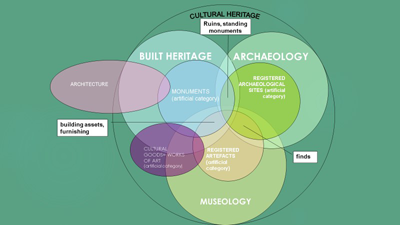

Considering the question of what the decision is about, I have three remarks. First, the relevant decisions target only a minor proportion of cultural heritage elements. As seen in Figures 7 and 8, it is clear that heritage protection built exclusively on legal regulations cannot be effective. Decisions are made mostly concerning protected elements, the ones currently under legal protection, but what about the rest? The listed monuments, the inventoried museum objects or the registered archaeological sites represent only a minor proportion of the physically existent cultural heritage. However, the state administration can only deal with registered items. Therefore, most of the known decisions focus on only a small, selected group.

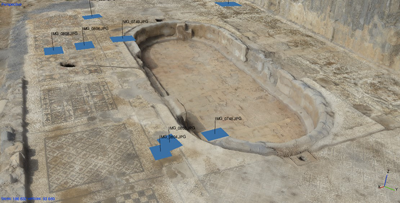

Secondly, decisions are based on artificially-generated records of dubious origin. Thanks to recent technological developments, current excavations can be documented in 3D and 4D, including full digitalisation down to the nearest millimetre, laser scanning, and 360-degree time-lapse videos. However, this documentation of the excavation that should be professional and precise is often carried out by non-professionals on one hand. On the other hand, and there are of course exceptions, the majority of the physical excavation work itself (i.e. the work generating the objects to be documented), at least in Hungary, is still executed by local manual workers who might have some experience after a while, but were never educated for the job (Figure 9; Figure 10). The work method is also uncertain. Some sites are located and their limits drawn following desk-based research only, without a site visit. Others are based on old data from museums or from aerial photos that were never checked in the field. Some have variation in their recorded location. If the contour was drawn with a highlighter in the early archaeological site register, the neighbouring plots in the land cadastre will also have to face excavation regulations. The reliability of the official archaeological site register which forms the basis of the administrative work and the actual protection activities, can be questionable.

Thirdly, the evaluation of sites (fundamental for making decisions) is not objective, since it is based on the subjective definition of heritage value. Despite the different interests and viewpoints of professionals and non-professionals, the reputation of an archaeological element can be a developed one (when the values are obvious) or cautiously determined i.e. artificially built up (when it is not so obvious). Considering the similar case of artworks, one can compare the original values of a Leonardo vs. a Picasso painting. Both were great artists, but which one would you buy without knowing the painter? The situation is the same if we compare a gorgeous medieval castle to a pit-hut site. One may be obvious even for non-professionals, the other has only information value, which has to be explained by professionals to become comprehensible and popular. Branding is important, but this is already a decision.

The significance and responsibility of making decisions is both over- and under-estimated. Drawing a conclusion about the subject of our decisions, I am afraid that we just live in an illusionary world of decision-making.

In order to understand the decision-making mechanisms in archaeological heritage management, the question of environmental management in a globalised world, which the built and historical environment is a part of, is unavoidable. Considering the environment of the decision, I have again three definite remarks.

First, decision-making must also consider global tendencies. The ways of using both human and other resources require other considerations if the goal is a sustainable development, and different considerations in the case of maximising profit. This difference has influence on everything in our globalised world. If comparing production mechanisms in the EU and China, we can see for example a smog-free factory in Germany and the smog in Beijing, which are simply a result of economic effectiveness vs sustainable development. Translating this situation into the language of cultural heritage, the costs of a preliminary excavation are very high, diminishing the profitability of a development in all those countries that intend to follow the Valletta Convention. These countries will have a disadvantage in the short run in comparison to other countries, which do not pay attention to such problems by requesting extra funds, time and administrative burdens from the developers. The advantage in the long run of having a more liveable environment does not actually count for the investors; that is why states have to decide about how strictly they wish to protect the immovable cultural heritage. Hungary had been a leading country in providing full protection for its archaeological heritage since 2001. However, this has changed since the economic crisis, as it is reflected in its new cultural heritage policy after 2010 (Figure 11). The importance of protecting archaeological heritage, even at the expense of developments, simply evaporated. Nonetheless, it is not only the Hungarian government who started adjusting its cultural heritage system. The reorganisation of English Heritage and its counterparts in the UK or INRAP in France goes back to the same considerations: developments and developers have to be nationally regulated in a worldwide competition of globalised economy, slowly balancing out sustainability and profitability.

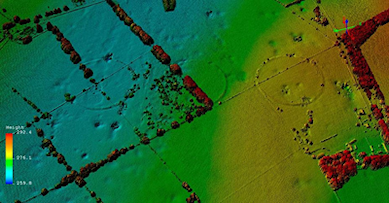

Secondly, ongoing rapid technological development not only provides new solutions, but also reveals problems to be solved. The current technological innovations in detecting sites or documenting excavations (such as LIDAR, satellite image analysis, Laser-scanning, 3D and 360-degree drone video) brings a never-before-seen amount of data and precision in their management (Figures 12-13). However, the future and current problems of managing this data are not always discussed. Both the data storage devices (regularly new tools and standards appear, while the previous ones gradually disappear) and the data formats (too many new launches in a very short time) are problematic. Who remembers the floppy discs? And who has a driver for them? Data storage and data management in a digitised world is a significant problem, which is often not considered by most professionals. The CD/DVD format are also digitally fragile. Most of the excavation documentation of the last couple of decades was submitted to the Hungarian authorities on these media. The non-centralised and under-financed data storing centres (e.g. the county museums in Hungary) are not able to deal with challenges such as regularly refreshing and transferring data into new formats and storage devices. However, without this regular work the whole of the completed preventive archaeological work will become useless and the delay for the investors becomes meaningless. We (cultural heritage professionals) have never had enough information, yet now we drown in data and suffer from losing it at the same time.

Thirdly, we have to accept the fact that the cultural heritage management — just like everything else in this world — is strongly influenced by politics. For whatever reasons, people fighting for votes are less sensitive to minor problems of a profession, often not even considering long-term goals of a discipline. And so in Hungary, monument protection and archaeology were depreciated to almost zero in seven years, and politicians took direct control over the field. When reviewing the preparedness of the relevant politicians responsible for the decisions in the cultural heritage field, things seem to be clear. However, these are the people who make the real decisions about archaeology, and there will always be an expert who can be cited/referred to in order to support their current interest.

Concerning when a decision is made, it is neither about time or about before or after the excavation, but rather about the tendency (following predominantly the changing legal regulations) and about the changing experience of the decision-makers, which, theoretically at least, develops over time. The most apparent example is the rise and fall of the polluter pays principle and how it was/is reflected in the various interpretations of the Valletta Convention. In some countries, this was considered a simple recommendation, which, therefore, did not influence seriously the previously existing heritage management structures. Some other countries thought the Malta Convention was a strict regulation. Thus, for example, in Hungary 100% of every element of an archaeological site had to be rescued with the costs completely covered by the developers. One can imagine the boost in the money circulating in archaeology after this new regulation had been introduced. However, without requesting all the steps of a preliminary excavation (including the submission of complete, digitised documentation and publication of the results) and allowing certain participants of the procedure to focus only on the on-site work, the Polluter Pays Principle has no defence against the developers' lobby. Even if 100% of an endangered archaeological site has been excavated and documented on-site (even at a cost of millions of Euros and over many years), but with zero percent of the excavation results used for the public or for the discipline, then zero Euros and zero days of research would have led to the very same outcome (but without negatively influencing the perception of archaeology and hindering the development). With a very high number of such cases, the changing relationship of politicians to this principle (and directly to the archaeological heritage management system) as an answer to the economic crisis and the global challenges can be understood and clearly observed in the current situation, also providing a new legal framework for administrative decisions. Considering time, therefore, the only constant is change, which inevitably influences decisions taken.

When asking why a decision is made (and I mean why do we have archaeology at all), I will highlight the three major purposes. Firstly, research and science was once upon a time the scientific purpose; this was the only motivation for the professional community, although it still goes hand in hand with the lack of an adequate financing, at least in Hungary (Figure 14).

Secondly, archaeological heritage is considered as a resource to generate value for tourism, employment, GDP in general, and the state. Every site and find has the potential for that, but many other factors are influencing whether it will be a success at the end or not (Figure 15-18).

Thirdly, the rescuing of finds and information is not important for developers, but rather for the state and its citizens. And so when making decisions, one has to consider the combination of these — and maybe many other — goals. Since decisions currently are mostly development- and rescue-driven, but without a comprehensive follow-up, their appropriateness is questionable.

For whom is the decision made and are the sites protected and managed? Our audience is very complex and is constantly changing; therefore, making decisions about archaeological heritage has to consider several recent trends and tendencies. First, a good measure for the success of the archaeological discipline is the feedback from the public. While most people know celebrities from their country, maybe even some politicians, poets, writers, and painters as well, representatives of scientific disciplines are usually less famous. Although the awareness and reputation of archaeologists is hard to survey, my standard question at conferences used to be: who are the most well-known professionals? Based on the answers, the fictional characters (Lara Croft and Indiana Jones) had far more reach in this respect than real life. Despite this, the situation cannot be much different in other European countries (Figure 19). Celebrities for the profession are needed to build up marketing and communication tools and be the public face for cultural heritage.

Secondly, there has been a conceptual change in the definition of heritage since the emergence of the so-called New Heritage which emphasises the individual's relationship to heritage instead of a traditional, state-declared value (which is mostly based on the interpretation of professionals). The definitions are about national education of the crowd versus an individual perception. Consequently, the society in general is not fully motivated anymore to protect heritage objects declared as worthy for protection by the professionals and the state. It is very difficult sometimes to explain to certain social groups why the local heritage belongs to them and why they should care about it. For example, several countries/states /nations are proud of their Viking past and cultural heritage. Their 'new' inhabitants are also proud of this heritage. Migration also influences cultural heritage issues, but this aspect is often ignored or not sufficiently taken into account either by professionals or politicians.

Thirdly, decisions always have to consider generational questions as well. For example, while a special tool is relevant to address content and message to reach one group, it can discourage the other. How can we involve the young generations in protecting real cultural heritage beyond the virtual space? Currently, digitisation, interaction and gamification are the key elements, while simply exhibiting objects is no longer interesting enough. However, the tendency may soon change again, when realising that to have real value one has to go back to the original object, not to its virtual versions.

Despite age, gender or interest, the involvement of all people in heritage protection would be the optimal situation. Therefore, it matters whether cultural heritage is only part of everyday life, or if it is just 'behind the scenes'. The overall social acceptance and support of archaeology is mostly minimal and this is not properly taken into account by professionals. Consequently, the efforts to change this situation are inadequate and not sufficient.

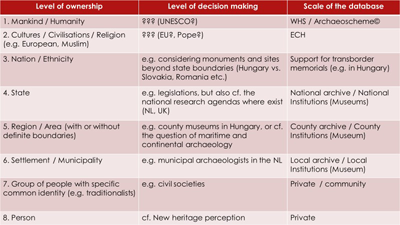

When talking about whose heritage the decision is about, we have to consider various levels of ownership, each having its own characteristics (Figure 20). It is important to understand that decisions can be made at various levels at the same time, each having influence on each other. Although the well-known phrase suggests to 'think global and act local', currently we think local (what has the actual investor to do with the site, how can I protect it or what can I ask from the developer in exchange?), but act according to global patterns in decision-making (e.g. by following the widely accepted Polluter Pays Principle). Considering the levels of ownership, this should perhaps be reversed as it would be beneficial to really think global (i.e. if you have to decide about an element of the archaeological heritage, be aware of the fact that this element belongs to the overall cultural heritage of humanity), and act local (maybe I serve the general aim of humanity better if I dare to lose this element of the heritage). Does such a procedure need standards? Very likely it does. And for what levels? Logically, for all levels, but creating standards will be easier for a database than for the decision-making process.

There are a number of ways, how we can approach the same problem. It is dependent on the role and goal of the decision-making person. Considering how the decision is made and how the sites are protected and managed, I have encountered seven categories.

Different views mean different approaches, but well-founded decisions have to be based on a holistic consideration. Decision-makers with limited viewpoints and experiences may more often lead to the poor results.

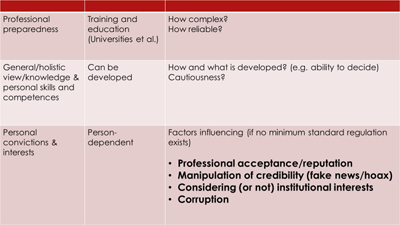

Last, but not least, it is important to investigate who is making the decision. The knowledge of the archaeological profession in itself is often not sufficient, although its existence would be a basic prerequisite. Still, many of the decision-makers, even state officers, have no proper education in and/or insufficient experience of archaeology. The individual aspect of a decision is always underestimated. However, the personal goals and the several influential factors are of special significance (Figure 21). We should always be prepared for attempts to influence by stakeholders who were/are/will be adversely affected by the decision. These attempts are not always friendly or positive.

The decision-making procedure in archaeology is complex and complicated. It is time we figured out how to handle situations in general and make professionally well-founded, but holistically considered decisions. First of all, what is a good balance, how to get a free hand at decision-making and how far can you go? If there are rigid regulations with thoroughly worked out standards, the decisions will be always similar and standardised. Such a structure will have challenges managing special situations, but on the other hand, giving space and flexibility for personal decisions based on professional knowledge may result in the changing quality of the decisions. So, do we need standards or do we need flexibility, or is the magic solution somewhere in the balance? In this case, the question is whether there is a decision-making mechanism that can serve all interests equally or, at the very least, adequately. There are three (four) possible answers.

I would like to thank my wife, Réka Virágos for her support and encouragement. She worked hard to ensure all the necessary conditions for the preparation of the presentation during the symposium and this article, partly by making it possible that I had the sufficient time to work on the manuscript and partly by providing feedback and corrections. I also gratefully acknowledge the general support of the EAC for offering the possibility of presenting this presentation at the symposium and its subsequent publication.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.