Cite this as: Virágos, G. 2019 Communicating Archaeology: The magic triangle, Internet Archaeology 51. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.51.5

This article is about the communication of archaeological heritage, presenting an overview of what I see are the major problems and the theoretical background. Starting with a personal experience, I would like to recall the way I found the title. My first idea was to connect it to the Matrix film series. Then I thought to be less humorous but far more precise and to provide a thorough description of the subject: Eternal States of Matter, Changes of Cultural Heritage and Its Communication: Archaeology – Monument Protection – Cultural Heritage Protection – Historical Landscape; Exploration – Research – Authority – Presentation – Management – Utilisation. As I was told by communication experts, this was a very basic mistake in communication. It really looked like a book title from the 18th century: over-sophisticated, boring and unnecessarily long-winded. Instead, it was suggested I call it Cultural Heritage 2.0. They are absolutely right; this is really comprehensive, expressive and trendy. Well, to me communication seems to be a sensitive and far reaching issue. Although I understand the point made and am in favour of the idea, I finally decided to use another title.

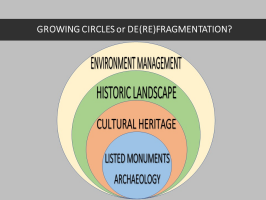

I would also like to clarify exactly what we are trying to communicate here: archaeological heritage. For over a century, the circles of cultural heritage issues expand and shrink (Figure 1). At the moment, we appear to be leaving the scope of cultural heritage and start thinking in terms of historic landscape, and I am convinced there is at least one more step forward in the coming decade before the likely defragmentation will become dominant again. This article, however, focuses only on the archaeological aspects.

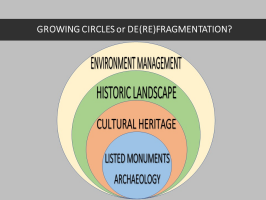

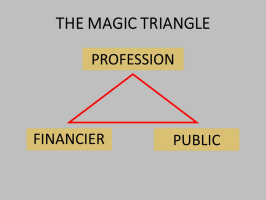

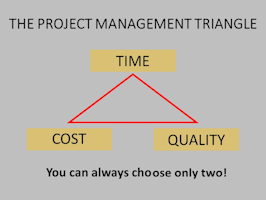

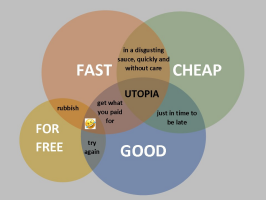

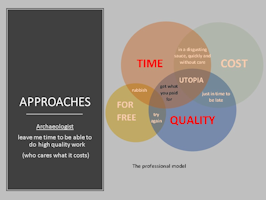

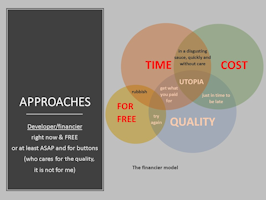

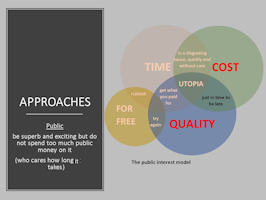

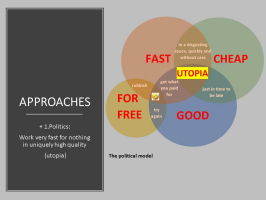

Communicating archaeology is about the relationship of the three major stakeholder entities: profession, public and financier (Figure 2) (I use the expression 'financier' instead of the usual word 'developer', because financier not only includes developers but, more generally, all the parties who appear in the archaeological process as direct clients and customers). I chose the concept of the triangle, because it can be applied to so many situations. Literally, it is a reflection of the eternal complexity, but more concrete and more relevant is the way it is used by management, known as the classic example of organising procedures. There are always three major factors or characteristics: time, cost and quality (Figure 3). The trick is that you can only ever choose two (Figure 4).

We can apply the same procedure to the magic triangle of archaeological stakeholders, who all have different approaches. In the professional model cost is mostly irrelevant (Figure 5). In the financial model the focus is not on quality (Figure 6). In the last approach, the public is usually less interested in time (Figure 7). Of course, there is one more theoretical model, imagined and enforced usually by politicians, but that is a utopia (Figure 8).

However, with such divergent interests, it is important to consider the opinion of these groups about each other. We, the professionals, often think of ourselves as superheroes protecting the common past, while others see only the small and unimportant, or on a more positive note, small and exotic species (i.e. the archaeologist). The financiers (or developers) often see themselves as kings of the road, while the others only see the financier in its pure reality (the one who has the money). Members of the public generally consider themselves to have a central role in everything (i.e. being the king, everything happens only for 'me'), while others have completely different opinions. Based on my own experience of the last 20 years, there is a completely subjective judgement of the stakeholders' significance (Figure 9). According to this, something is not complete in this whole system. The needs and interests of the three major stakeholder groups are very different, and sometimes even in opposition.

Being archaeologists, our duty is to reconsider what is missing from the profession side to ensure smooth cooperation with the two other parties. What kind of knowledge, skills and competences shall we master to be effective in communicating with each other?

Archaeology needs sales managers. Whatever the product, it has to have a shiny cover for better sales. We know that archaeology today is a very complex process, ranging from geophysical surveys, trial-trenching and excavations, through post-excavation analysis to reconstructions and exhibitions. Why do we think that it is not enough to understand the process and know some of its elements, but also have to master and execute everything as one single person? According to the legal regulations in Hungary, archaeologists are responsible for everything in the whole excavation process. This is a nonsense and you cannot be prepared for it any more simply because of its complexity.

Let's take another example. In the car industry, the engineer is responsible just for making plans. It is a very complex job anyway. The manufacturer is producing; that is, there is a special team for the execution, who follow the engineers' instructions. Finally, there is a clear, complete product. However, none of these people or groups deal with selling this product. That is why sales managers exist, as this activity needs a completely different range of knowhow and skills than planning or manufacturing. Can you imagine an engineer or a craftsman trying to sell you a BMW? Even simply as drawings or car parts? This is what most archaeologists still try to do nowadays.

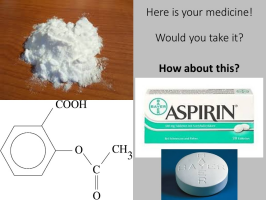

In another example from the world of medicine(Figure 10), what would you think if a chemical formula was offered to you with some white powder? So, why would it be normal for archaeology to do something similar, saying 'Here is your heritage. Do you copy?' (Figure 11). We are mostly on the right track but we have to pack in everything to be easily understandable, digestible and desirable, which requires special knowledge and special people.

Archaeology needs more effective marketing. The lack of branding affects most European countries and definitely all the possible levels.

On a personal level, we do not have really famous archaeologists. At least, not famous as far as the public are concerned. In most countries the most well-known archaeological names usually relate to sites, even according to Google. Fame only comes through popular culture, which is usually very far from professions. At an organisational level, people would recognise their national parliament or the local theatre, but hardly any of the emblematic organisations of archaeology (National Museum, Academic Institution, University Department, Local Museum, National Organisation or Specialised Company) would be recognised from their buildings nor their logos. This might be problematic for most professionals. Considering the sector (i.e. archaeological heritage and its management), there are more fortunate countries with emblematic sites built up as symbols by marketing over decades or even centuries: Stonehenge, Altamira, the Parthenon or the Colosseum are perhaps obvious examples. There are, however, some less apparent cases – the Jelling stones of Denmark, for example – and even less developed ones for many other nations. In Hungary, we do not really have a strong symbol for archaeology. Nowadays, perhaps the Seuzo treasure could be considered as such, but the intention to build up its profile is more a political than a cultural mission. Even this reminds us of the unfortunate fact that the credibility of archaeology is under constant destruction, at least in Hungary, partly as an internal activity of professionals and partly with additional support from the politics.

Public outreach is generally insufficient and not systematically considered. However, there are many aspects to a complex dissemination strategy, which should be the fundamental tool for communicating the results of our work.

Even more important is that when talking about the communication of something, its value has first to be identified. Monetary value is not a question for most people. However, physically there is no difference at all between any kind of goods and money. Still, you do not have to explain the value of money, as it is obvious, being learned during childhood, and is globally accepted. In contrast, you do have to explain the value of cultural heritage, because it is not obvious, not taught properly during childhood, and not meant to be global anyway. The value of archaeology is not clear to the public. This is the reason why the Concept of Heritage Community (Faro Convention) is still not working well. It is just an ideal, but neither the profession nor the individual states are working like that. So, when communicating archaeology, we have to start from the very basics, at least in all those countries where it has not already been communicated for decades. Moreover, for the general public in its widest sense, it has to be like political messages - simple: Archaeology is good/Archaeology is interesting/Archaeology is loveable etc. It also has to be personalised whenever possible. If the message is too global, it will not reach the single person effectively.

With regards to the methods of outreach activities, we are not always actively present during communication. In most cases, an intermediary or tool, such as a journalist or a website, sits between the profession and the public. Therefore, it is interesting how archaeology appears in the everyday news, as this is the most general form of meeting with the public. And there we have a problem, at least in Hungary. I only know three major types of relevant news. The first has no real meaning, as such news seems interesting but lacks credibility. Most of them start with 'Australian scientists have discovered…' (or something similar), generating interest and making it hard to control. This leads to the general problem of REAL NEWS vs FAKE NEWS. The second has no real meaning as it lacks understanding of the subject. It provides correct data, but without a reason e.g. 'Archaeological excavation has revealed pottery fragments, holes and bones, which are the remains of a settlement'. BORING. The third has no real meaning either as it lacks clarity for non-professionals. This is the case of the 'I speak science' situations. The professional is unable to imagine that other people were not educated for five years as archaeologists.

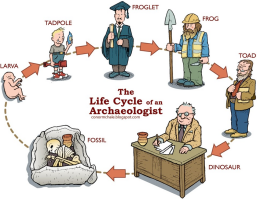

We should also bear in mind that journalists are interested in their own story told for their own audience. That is why archaeologists also have to have their own stories for their own audience. For this reason, we would need lots of Gerald Durrells, David Attenboroughs or Jamie Olivers in archaeology (By the way, being able to refer to well-known persons only from the UK is again an interesting feature). Once being able to communicate directly with the public, why do we think that only the written publication and the exhibition counts (as these are required by legal regulations in most countries)? Of course, on the one hand, we have the usual structures, which are available for all stakeholder groups (i.e. for professionals, developers and the public), such as professional periodicals and books, and also magazines in most European countries, or more recently even blogs, apps, social media or podcasts. On the other hand, a wide variety of old and new methods are now available for a more effective and more specialised dissemination: participation in creation (even a drawing competition for children or just cooking a special type of cake), performing or any other arts, movies, games, etc. Today, gamification is for the future generations. Its importance cannot be overestimated, but for the moment, no ground-breaking solutions have been developed. The VR/AR/MR (i.e. virtual, augmented and mixed realities) are also predominantly for younger generations, and this is a rapidly developing field in public communication. Movies are also ever-green solutions, and they are working (remember the Indiana Jones and Lara Croft films). Cartoons are always fun, fun means enjoyment, and learning is easier and more effective if it is enjoyable (Figure 12). Finally, we have the 'more serious' tools, such as the fun literature, the contemporary or experimental archaeology, and the festivals and re-enactment occasions.

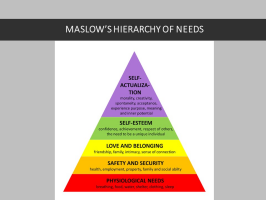

Insufficient social support is also a missing element for more successful communication about the archaeological heritage. The famous hierarchy pyramid of Maslow is about the levels of needs of all persons. The needs enrolled into the higher levels are not interesting as long as the lower ones are not fulfilled. In other words, 'luxury' needs are not supported if the basic problems are not solved (Figure 13). We can draw a similar pyramid for the needs of archaeological heritage. We can also locate cultural heritage on the Maslow pyramid of each person, or on similar hierarchy pyramids of other segments, such as the society or economy, or of other interests, such as politics. Considering the level of hierarchy for archaeology, it belongs to the top of the pyramid for most of the segments. Members of a society are first interested in basics like health care and security. Archaeology belongs to the 'luxury' level. Considering the hierarchy level of archaeological heritage according to the social needs or needs of society in general, the needs of a state or the state administration, environmental or economic needs, archaeology will very likely always be given the 'luxury' label. The only exception is perhaps the economy, where cultural heritage is now part of the basic kit as a resource for the creative industry and tourism.

Although cultural heritage is not simply a matter of leisure and art any more, it is still mostly estimated as a luxury category. Therefore it is not very well supported. However, changing anything would require wide support; consequently, the need for cultural heritage has to be generated first. Then, we can bring archaeology down the pyramid of needs from the peak. Believe, convince and build up trust, otherwise do not expect progress in cultural heritage management. We should develop a demand for cultural heritage to create a more independent future for it, and communication is the key factor in this process.

Let's look in more details on how this whole question of support is working (or not). The most obvious sites for the public are the world heritage sites. Logically, these are the most well-known and best protected elements of our cultural heritage in the world. Still, even these sites are often endangered or destroyed. This has happened in the last decades, even more recently, and even in Europe.

In the light of all of these examples the question arises: how can it happen that the world organisations and the states are unable or unwilling to protect the very top sites, while you cannot extend your own house because of a few pottery fragments in your back garden? How do we expect to have support from others as long as this is not an adversarial situation?

Of course, the most important factor cannot be left out: money is needed for everything. The reason why a communication activity is financed will always influence that communication. It is, however, not evident – or, at least, should not be evident – that funding trumps everything.

Up to this point I was considering what is missing from the professional side in order to have good cooperation with the two other parties, in particular with the public. Now, what to do with all of this? What can we do to replace or complement the existing system? In my opinion, the solution is education.

First of all, the rapid development of technologies would be good practice to follow. On the one hand, almost every year some new technology appears or develops further e.g. remote sensing and aerial photography (lidar, satellites, drones, etc.), geophysical survey, laser scanning. Still, how many archaeologists are familiar with all these methods? And these are only some surveying technologies. There are rapidly changing communication technologies. However, some members of the various (especially the older) generations are not competent with all these tools, causing inequalities and disturbances. But the fact remains, communicating archaeology to the public requires the knowledge of all the actual technologies of both communication and the profession.

A balance between overall knowledge (i.e. the bird's-eye perspective) and detailed perspective (i.e. mining into the depth) has to be found.

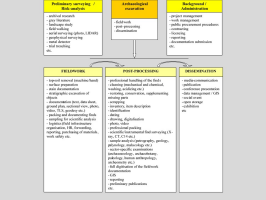

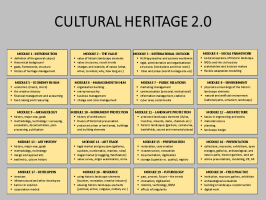

On the one hand, the process of an archaeological excavation is very complicated, and it is more than preferable to have at least an overview of the whole procedure (Figure 14). But you do not have to do everything yourself. On the other hand, an archaeologist has to be familiar with several other disciplines to run an excavation successfully, execute projects or carry out research. But you do not have to be proficient in all of them. And here I come back to one of the potential titles of this paper: Cultural Heritage 2.0. This should represent a new approach in educating future archaeologists. The education should be renewed to offer a holistic perspective, including subjects not directly connected to the heritage field (Figure 15). I am sure, as public education gradually gives up its current education methods and puts the emphasis on developing skills and competence instead of simply facts and data, tertiary education will soon follow this trend, including in heritage management.

Professionals have to have state-of-the-art scientific knowledge. This is, however, a very difficult expectation because of the rapid changes. Clearly, there are generational problems. Not in the sense of personal ages, but in the sense of scientific phases. Before the 19th century, one major change took place over a period of several generations. After the 19th century, several changes took place during one generation, and the speed of change is rapidly accelerating. We have to react somehow to this process, but how to keep up with all the changes?

a) Science and Artefacts – ~1950s-1990s – material science

In the post WWII era, archaeologists primarily focused on scientific questions. Excavations were usually small scale (generally a few 100m² maximum), time was limited only by the budget (no prescribed deadline was set in most cases), and material science played the leading role. To give it an archaeological definition, I would call this era the 'Level Culture' (or more precisely, following the German terminology, it can be called the 'Stufenkultur'. Its typical features are:

Between the 1950s and 1990s, archaeologists worked primarily for the profession: Generation 1 – the aim is to meet the expectations of the profession. Low budget, good results, much time, much fun – the professional model of the management triangle can be detected.

b) Documentation and Administration – ~1990s-2010s – data administration

Subsequently, at least in Hungary, everything changed after the 1990s. Owing to political changes, but even more because of economic growth, the volume of excavations increased. The previous methods were no longer suitable. Administering the data became the benchmark. To give it an archaeological definition, I would call this era the 'Valetta Culture' (or also the 'Harris Matrix Culture', referring to the basic ideological tool behind the documentation). Its typical features are:

As its ideology was based on the 'polluter pays' principle, between the 1990s and 2010s this was the period when archaeologists worked predominantly for the developers: Generation 2 – the aim is to meet the expectations of the financier. High budget, no time, not much fun, and lots of unfinished work. I think, the financiers' model is discernible.

c) Presentation and Digitisation – from ~2010s – info-communication

Finally, the last decade has been more and more about 'info-communication'. The focus is on clear interpretation of the results. To give it an archaeological definition, I would call this era the 'Media Culture' (or also as the 'VR Culture', referring to the growing significance of the virtual world in elaborating, interpreting and digesting information). Its typical features are:

Since the 2010s, archaeologists work predominantly for the public, and the elements of the public interest model are present: Generation 3 – the aim is to meet the expectations of the public.

It is hard not to see the presence of the magic triangle and the constant friction between these basic stakeholder groups. But are there peaceful or exterminating transitions in this 'Game of Cultures'? Archaeologists have had to deal with compliance constraints from the profession, the financier and the public for the last 60-70 years. While all stakeholders are present simultaneously, there is always a dominant one whose expectations control the major motivation. However, the problem is that education cannot follow this rapid change in the procedure. Universities, professors, state education strategists are not prepared for such flexibility. Despite becoming an archaeologist in the 1990s, I was educated largely according to the standards of the 'Stufenkultur' but had to work immediately according to the standards of the 'Valetta Culture', while my actual knowledge has almost nothing to do with the recent expectations of the 'Media Culture' and is surely even less connected to what is coming.

The intriguing question is always: what is coming? Will the circle start again, and will the profession focus again on the material culture of the ancient people, disregarding the expectations of the state, the widest public and the developers? The new golden age for the profession is waiting for us? I do not think so, and if you think this has a happy ending, you haven't been paying attention.

What's next? ... d) Big Data Management and AI – from 2020s?

My vision is that the future of archaeology is about big data management combined with artificial intelligence. The Google image search algorithm may be taught to recognise typology and dating of pottery, style and era of a building element etc. The Google street view is already able to estimate the income, the residency and the political orientation of the people found on the street, but it can also estimate the cultural origin, the function and the dating of an archaeological object in the future. Maybe in a few years, maybe in a decade, our work will be very different from that of today. Whether we like it or not, AI is also coming in archaeology. However, it also means that the needs and interests of the magic triangle parties can be better satisfied. This is of course only my personal view, but we can come back to it in a decade to see whether it was right or not.

I would like to thank the support and encouragement of my wife, Réka Virágos. She worked hard to ensure all the necessary conditions for the preparation of the presentation and this article, partly by making it possible that I had the sufficient time to work on the manuscript and partly by providing feedback and corrections. I also gratefully acknowledge the general support of the EAC for offering the possibility of giving this provocative presentation at the Symposium and publishing it in Internet Archaeology.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.