Cite this as: Gaunt, K, van Tongeren, T. and Christie, C. 2024 Fenland Fields: Evolving Settlement and Agriculture on the Roddon at Viking Link Substation, Bicker Fen, Lincolnshire, Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.10

Archaeological investigations at the Viking Link Convertor Station, Bicker Fen, Lincolnshire, uncovered two main periods of activity. Roman and Saxon features were identified, concentrated on relatively high ground in the Fen landscape extending across a roddon - an area of raised land formed as a result of infilled tidal creeks and estuarine streams. The excavations were undertaken by Headland Archaeology (UK) Ltd for Ian Farmer Associates (IFA) as part of the mitigation works relating to the construction of an electricity interconnector between Revsing, Denmark, and Bicker Fen, Lincolnshire (Figure 1; Headland Archaeology forthcoming). The cable route extends through the authority areas of East Lindsey District Council (ELDC), North Kesteven District Council (NKDC), Boston Borough Council (BBC) and South Holland District Council (SHDC), with a Converter Station building to be constructed in South Holland. The Viking Link Convertor Station site is located to the north of North Ing Drove, Donington, Lincolnshire (TF 18709 37380).

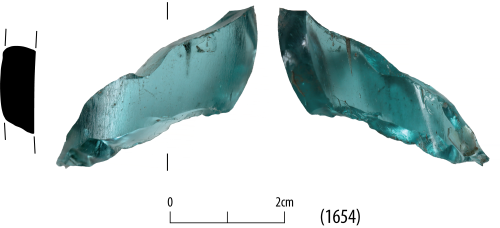

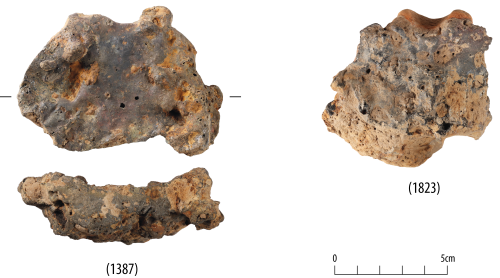

The Roman activity, concentrated within excavation areas SMR1, SPE1 and SPE2, comprised part of a complex farmstead characterised by a ditched enclosure system with evidence for maintenance and modification. The finds assemblage, radiocarbon dating and subsequent Bayesian modelling indicate activity occurring from the 2nd to 4th/5th centuries AD. The pottery assemblage included grey wares, some colour-coated and samian ware, and a tazza, used to burn incense, which can be dated to the 3rd or 4th century AD. Other Roman-period finds include a glass bead, worked bone and worked stone. The animal bone found in relation to the Roman-period features is dominated by cattle, with the presence of mature as well as juvenile individuals. There is also evidence to suggest the handling of cereals during this period in\cluding glume wheats, free-threshing wheats and barley.

The Anglo-Saxon field system, consisting of boundaries and enclosures, extended over the excavation area SMR6 immediately to the east. The boundaries are narrower than the Roman-period enclosures and more curvilinear in nature. They are also more short-lived and show many maintenance phases. This probably indicates landscape use on a seasonal or ad hoc basis, rather than a more permanent utilisation. In addition to Anglo-Saxon pottery, finds from the period include a fragmented bone comb that dates between the mid-7th and 10th centuries AD. The pottery, comb and radiocarbon dating suggest that a mid-Anglo-Saxon date is most probable. The zooarchaeological assemblage includes evidence of cattle, horse, pig, sheep, goat, chicken and goose. The importance of fish as a food source rises relative to the Roman period, as is evidenced by remains of cod, flounder, flatfish, garfish, scad, salmon, pike and spined stickleback. The palaeobotanical assemblage indicated the presence of cereal crops, primarily barley, and pulses including broad bean and pea, which may have been cultivated as part of a seasonal rotation.

Roman Lincolnshire | Anglo-Saxon Lincolnshire

The site at Bicker Fen sits within a rich archaeological landscape, with cropmarks of possible Roman date including field boundaries and trackways identified largely situated on roddons. Saxon activity is also noted with artefact scatters, industrial activity and settlements to the east and south of the site, including Donnington. As a result of this, prior to mitigation archaeological works generated a desk-based assessment (Arcadis Consulting (UK) Ltd 2017a), Aerial Photographic and Lidar Assessment (Trent & Peak Archaeology 2017), Geophysical Survey (Headland Archaeology 2017a) and Trial Trenching (Headland Archaeology 2017b).

During the Roman period, Lincolnshire was home to two major roads that connected the city of Lincoln (Lindum Colonia), with key Roman settlements in other parts of the country. Ermine Street connected London with York, crossing Lincolnshire between Stamford in the south and Winteringham on the bank of the Humber in the north. The second Roman road is Fosse Way, which connected Lincoln with Exeter via Leicester, Cirencester and Bath (Margary 1967). The presence of a regional centre as well as significant infrastructure benefitted the entire region, influencing the development and distribution of settlements.

The Roman legionary fortress of Lindum was founded at the earliest during the reign of Emperor Nero (AD 58-68). It was most likely after AD 86 when Lindum was awarded the status of 'colonia', or a settlement for retired soldiers (Jones 2002, 34). As it developed, the settlement became a hub for social, political and economic activity and a second enclosure was added. The original settlement, or upper colonia, was walled in the first half of the 2nd century AD while the lower colonia - the new enclosure - was given walls during the late 2nd or early 3rd century. Archaeological evidence for the settlement includes a forum, baths, temples, buildings and shops (Whitwell 1970, 27). The importance of Lincoln as a regional centre is further underlined by the likely presence of a Bishop of Lincoln at the Council of Arles in AD 314 (Jones 2002, 119). During the last century of Roman presence, the city developed further, and the influence of Christianity becomes more widespread. Lindum Colonia not only profited from the presence of two major roads, but also from strong connections with other settlements and the North Sea via canals. The Fosse Dyke Canal, for example, connected Lincoln with the Rivers Humber and Trent as well as with the North Sea (Cumberlidge 2009). Car Dyke connects the River Witham near Lincoln with the River Cam near Cambridge and runs from there across the Fenlands to the Wash (Bond 2007). Accessibility of the marshy area improved with the construction of the so-called Fen Causeway, which ran between Denver in Norfolk and Peterborough, where it connected to Ermine Street (Hall and Coles 1994, 107-8). The trajectory of this road was situated some 35km (21 miles) south of the excavation site, suggesting that its direct impact on the site's activity may have been limited. However, to the south of the site lies Salter's Way, believed to originate in the Roman period, connecting Donington with the settlements of Saltersford and further afield (Arcadis Consulting 2017b, 35).

Extensive Roman activity surrounding the site at Bicker Fen was noted to the south of Salter's Way including a large cropmark complex, settlements and possible salt production sites (Figure 2). Several salt production sites were noted to the west with further settlements to the north. In general, it can be stated that Romano British settlement in the northern Fenlands had a small and rural character (Hall and Coles 1994, 111). Pottery assemblages found suggest a limited prosperity for the settlements, and zoological assemblages as well as field and enclosure systems are indicative of agricultural land use. Any industry in the northern Fenlands seems to have taken place on a small and local scale. Evidence for more widespread iron working and pottery production can be found on the western Fen edge (Hall and Coles 1994, 112-13). Along the edge of the Wash, roughly between Wrangle in the north and Downham Market in the south, various settlements are related to salt production, as is evidenced by the presence of salterns (Hall and Coles 1994, 115-19).

One of the most underexplored periods in British archaeology is the transitionary phase between Roman and Anglo-Saxon influence. In general, it can be assumed that there was some degree of continuity in the everyday life of people living in Lincolnshire, but it is evident that change was imminent. Lincolnshire is situated in the part of England that was colonised by the Angles, a people originating from the current border region between Germany and Denmark. The Angles settled in the part of England approximately between Ipswich and Cambridge in the south and Leeds and York in the north. It is likely that Lincolnshire was initially part of a small tribal kingdom named Lindsey, which was absorbed by Northumbria in the 7th century (Higham and Ryan 2013, 138-40).

The Roman city of Lincoln declined during the late 4th century, but it is unlikely that it was completely deserted. The church of St Paul in the Bail was built within the Roman forum in the late 4th century. A larger building replaced the initial church in the 5th century and was demolished during the 6th century (Higham and Ryan 2013, 40). This evidence suggests a gradual transition from Roman to Anglian influence. Roman Christianity was apparently not abruptly replaced but existed alongside Anglian paganism for at least some time.

In contrast to funerary evidence, early Anglo-Saxon settlements are a rare discovery in most of south and south-east England. Settlements are more frequently found in East Anglia and the East Midlands, but especially the earliest sites remain elusive. The Fenland Archaeological Survey found that early and middle Anglo-Saxon settlement locations are often relatively far away from later medieval towns and villages while late Anglo-Saxon settlement is found closer to later sites (Hall and Coles 1994 , 122). The presence of various large early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries in Lincolnshire suggests that there must have been a continuation of occupation. This is evident, for example, in the northern Fenlands, with the large cemeteries of Quarrington being situated approximately 17km (10.5 miles) north-west of the excavation site. An early and mid-Saxon settlement, including field and enclosure systems, was found to be related to these burial grounds. (Taylor et al. 2003, 231). In Sleaford, just north of Quarrington, more evidence was found for Anglo-Saxon burial as well as mid- to late Anglo-Saxon settlement. This place is mentioned in a charter from AD 852 as the location of a Saxon estate (Taylor et al. 2003, 233).

Even closer to the excavation site, two Roman sites at Gosberton and Pinchbeck see a continuation of use into the early and middle Saxon period. A total of nine Saxon sites were unearthed in and around Gosberton, some 6.5km (4 miles) south of the excavation site. All but one of these sites returned early Anglo-Saxon pottery and six sites also returned mid-Saxon pottery. The location of the Gosberton and Pinchbeck sites on low mounds was the likely cause of abandonment by the 9th century, influenced by sea level fluctuation. A further mid-Saxon site at Quadring, located on one of the highest roddons in the area, survived into the late Saxon period, as evidenced by finds of Stamford ware (Hall and Coles 1994 , 122-124). In general, there is limited evidence for industry in and around currently known settlements. Instead, the roddons seem to have been used for various forms of agriculture. In some places, including Pinchbeck (c. 12km/7.5 miles south of the excavation site) parts of the Romano-British land surface are covered by marine silt and silty clay, suggesting a process of flooding. It is thought that this flooding starts during the 4th century, and early Anglo-Saxon evidence suggests it had subsided by the 6th century (Hall and Coles 1994, 114). For much of the evidence, it is impossible to say whether it points at continuity from the Romano-British into the Anglo-Saxon period. While some continuation of ordinary rural life in The Fens can be expected, the evidence of flooding during the late Roman period suggests abandonment and later resettlement of at least part of Fenland south of the excavation site.

Remnants of the Romans: establishing enclosures | Expansion of the enclosure system | Continued maintenance | Transition | Anglo-Saxon agriculture

The backdrop of the excavations is the Lincolnshire Fen landscape. Geologically, this landscape is situated on a bedrock formation, formed during the Jurassic period, which is named Oxford clay. Historically, this part of Lincolnshire has witnessed regular sea-level fluctuations, resulting in an ever-changing coastline and the build-up of tidal flat deposits. As a result of these changing circumstances, the stratigraphy is currently dominated by loamy and clay-rich superficial tidal flat deposits and the groundwater level is high (BGS Geology Viewer; Cranfield University 2020, Soilscape 21). Roddons are a key feature of this landscape and influence the overall distribution and development of archaeological sites (Smith et al. 2010).

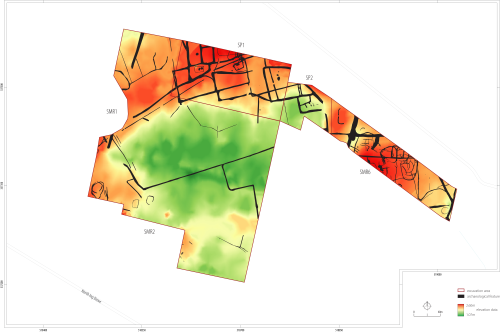

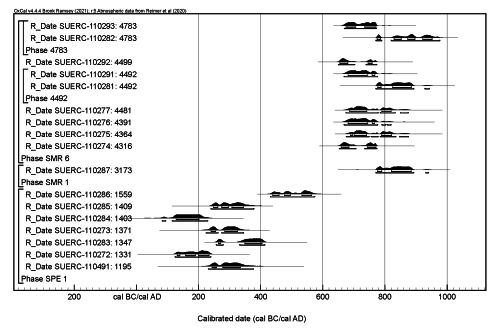

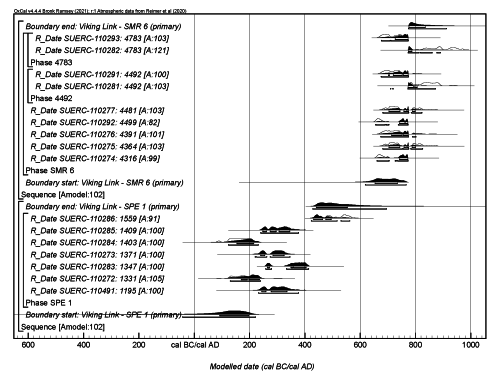

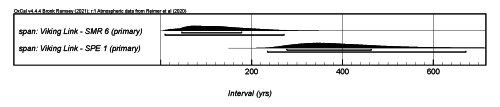

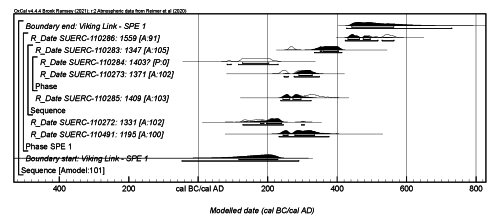

The excavations at Viking Link revealed evidence of Roman and Saxon activity extending across a roddon, with the extent of the high ground influencing the distribution of features (Figure 3). Roman activity was concentrated to the west comprising well-defined rectilinear enclosures with a droveway and possible structures. To the east, a busy network of Saxon boundaries and enclosures were uncovered that were more short-lived in nature (Figure 4). A programme of targeted radiocarbon dating was undertaken, with sample selection based on key stratigraphic relationships and suitability of material. A total of 17 radiocarbon dates were obtained indicating Roman activity from the 2nd to 4th/5th century AD and Saxon activity from the 6th to 10th centuries (Table 1).

| Lab ID | Context | Context description | Material dated | δ13C (‰) | δ15N (‰) | C:N | Radiocarbon age (BP) | Calibrated date (95% probability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPE1 | ||||||||

| SUERC-110491 | 1195 | Fill (1195) of large boundary ditch [1126] | animal bone: cattle; radius | -20.8 | 8.7 | 3.2 | 1764 ±29 | cal AD 230-380 |

| SUERC-110272 | 1331 | Basal fill (1331) of pit [1330] within enclosure | charred cereal grain: Triticum sp. | -23.0 | 1852 ±24 | cal AD 120-240 | ||

| SUERC-110283 | 1347 | Final/4th fill (1347) of ditch [1342] that contained copper disc | animal bone: cattle mandible | -21.0 | 8.4 | 3.3 | 1699 ±21 | cal AD 250-420 |

| SUERC-110273 | 1371 | Third fill (1371) of ditch [1401] | charred cereal grain: Triticum spelta | -22.2 | 1779 ±24 | cal AD 220-350 | ||

| SUERC-110284 | 1403 | Basal fill (1403) of three in ditch [1413] that contained Roman Iron Age pottery (100 BC-AD 400) | animal bone: chicken carpo-metacarpus | -20.0 | 12.6 | 3.5 | 1882 ±24 | cal AD 80-230 |

| SUERC-110285 | 1409 | Ditch fill (1409) in ditch [1797] | animal tooth: cattle; upper molar | -21.5 | 10.7 | 3.3 | 1751 ±24 | cal AD 240-380 |

| SUERC-110286 | 1559 | Basal fill (1559) of three in ditch [1983] | animal tooth: cattle; lower molar | -21.8 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 1553 ±23 | cal AD 430-580 |

| SMR 1 | ||||||||

| SUERC-110287 | 3173 | Basal fill (3171) of two in ditch [3252] | animal tooth: cattle; upper molar | -20.6 | 7.1 | 3.4 | 1191 ±24 | cal AD 770-950 |

| SMR 6 | ||||||||

| SUERC-110274 | 4316 | Only fill (4316) of ditch [4904], dumped deposit | charcoal: Alnus glutinosa | -28.8 | 1320 ±24 | cal AD 650-780 | ||

| SUERC-110275 | 4364 | Deliberate backfill, upper fill (4364) of pit [4362] | charred cereal grain: Hordeum vulgare | -22.5 | 1247 ±24 | cal AD 670-880 | ||

| SUERC-110276 | 4391 | Second fill (4391) of five in terminus of ditch [4814] | charred cereal grain: Hordeum vulgare | -22.0 | 1269 ±24 | cal AD 660-830 | ||

| SUERC-110277 | 4481 | Top fill (4481) of two in ditch [4479] | charcoal: Prunus spinosa | -27.6 | 1250 ±24 | cal AD 670-880 | ||

| SUERC-110281 | 4492 | Top fill (4492) of two in ditch [4908], dumped layer | charred cereal grain: Hordeum vulgare | -22.9 | 1186 ±24 | cal AD 770-950 | ||

| SUERC-110291 | 4492 | as SUERC-110281 | animal tooth: cattle; upper 4th premolar | -21.0 | 7.5 | 3.4 | 1273 ±21 | cal AD 660-780 |

| SUERC-110292 | 4499 | Basal fill (4499) of two in ditch [4911], dumped layer | animal bone: cattle; skull, petrous | -22.8 | 7.6 | 3.7 | 1333 ±24 | cal AD 650-780 |

| SUERC-110282 | 4783 | Basal fill (4783) of three in ditch [4871] | charred cereal grain: Hordeum vulgare | -21.0 | 1159 ±24 | cal AD 770-980 | ||

| SUERC-110293 | 4783 | as SUERC-110282 | animal bone: chicken; tibio-tarsus | -20.0 | 11.2 | 3.5 | 1285 ±21 | cal AD 670-780 |

The earliest activity identified within the excavation area at Viking Link comprised a network of large Romano-British enclosures, clearly part of a larger farmstead. This enclosure system was located on the southern edge of a silt roddon with very few features extending beyond (Figure 5).

A series of ditches potentially indicate the presence of boundaries pre-dating the establishment of the main enclosures. To the north, Ditch 1890, Ditch 1793 and Ditch 1620 are truncated by the main enclosures and do not follow the primary alignments. To the south-east, Ditch 1156 is aligned north-west to south-east and is truncated by the southern ditch of Enclosure 12. A small assemblage of Roman pottery was recovered from the ditches, with the majority recovered from Ditch 1793. The stratigraphically earlier ditches indicate that the observed Roman enclosures may represent the reorganisation of earlier systems of landscape management that do not survive in the archaeological record.

The core of the enclosure system covered an area 96m north-west to south-east by 194m north-east to south-west and was comprised of twelve identifiable rectangular enclosures (Table 2; Figure 6). The central area defined by enclosures 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10 contained two possible structures, pits and the remains of a droveway, which influences the organisation and development of the site. To the north three further enclosures adjoined the central area, enclosures 1, 3 and 4, with Enclosure 2 extending beyond the limit of excavation. A series of intercutting ditches were located in the eastern corner of Enclosure 4 from which a rich artefactual assemblage was recovered. The enclosures extended to the east, enclosures 8 and 12, with indications of boundaries continuing beyond the limit of excavation. The differing dimensions of these enclosures, which shifted to larger enclosures toward the southern edge of the roddon, highlights the potential differences in function as the activity moved away from the suspected focus of activity in the north.

| Enclosure | Area (Length x Width) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 35m x 15m |

| 2 | 3m x 9m |

| 3 | 22m x 13m |

| 4 | 22m x 34m |

| 5 | 22m x 22m |

| 6 | 18m x 28m |

| 7 | 20m x 51m |

| 8 | 18m x 27m |

| 9 | 20m x 53m |

| 10 | 25m x 48m |

| 11 | 11m x 46m |

| 12 | 36m x 71m |

The enclosures were defined by ditches that measured 1.6-4.7m in width and 0.13-1.07m in depth. The boundary ditches contained a variety of alluvial clay and silt deposits, many of which were noted throughout the full extent of the enclosure system, potentially resulting from the seasonal or regular flooding of the ditches. The 'U' shaped profile of many of these deposits indicates that most ditches were subject to regular clearance and maintenance, possibly also on a seasonal basis. It is important to note that these maintenance activities are likely to have resulted in the removal of much of the artefactual and environmental material from the ditches. Consequently, the datable material recovered from the site may be more representative of the periods of disuse and a cessation in clearance activities than the periods of maintenance associated with more active use of the enclosure system. Radiocarbon dating and analysis of the artefactual material suggest that commencement of this activity dates to the mid-2nd century.

A possible droveway was identified extending across the central enclosures and forms a key component of the enclosure layout. This droveway was visible within the excavation area running for a total length of 225m on a north-east to south-west alignment, defined by parallel ditches. The northern ditch, Ditch 1983, was substantial measuring c. 3m in width and 0.51m in depth. This ditch extended from the western edge of excavation to Enclosure 6, with a c. 5.5m gap before continuing through Enclosure 7 as Ditch 1401. Cereal grain from the third fill of Ditch 1401 was radiocarbon dated to cal AD 220-350 (SUERC-110273). The fill represents the later backfilling of the ditch, suggesting an earlier date for its construction. The southern ditch, Ditch 1902, was considerably smaller, measuring 1.18m wide by 0.3m deep and containing only a single naturally infilled deposit of clayey silt. The southern ditch follows the same alignment as the northern but terminates before reaching Enclosure 10 and may have continued beyond the enclosures to the north-east. At its widest point the droveway measured 8.5m in width, narrowing as it extended through the enclosures to 2-3m.

The droveway appears to form part of the earlier phase of the enclosure system, potentially for the movement of livestock between the enclosures and wider pasture. Sections of the northern ditch appear to have been recut but were truncated by later maintenance activities associated with the enclosure system, indicating that it was not in use during the later phases of activity at the site (see section on Maintenance)

Two possible structures were identified within Enclosure 6 and Enclosure 7. The remnants of both structures were identified only as shallow beam slots which formed rectangular enclosed spaces within the larger enclosures. No definitive evidence for upstanding structural remains were found.

Structure 1 (Figure 7) was located within Enclosure 6 and enclosed a space 13m by 8.5m. The beam slot, 1302, which comprised the exterior of the structure, measured 0.42-0.68m wide and 0.13-0.25m deep and contained a single deposit of alluvial silt. The additional presence of two pits within the interior of this structure suggests that this structure was not related to occupation and instead likely represents a small covered agricultural area, possibly for storage or industry. The two pits within the structure had distinctly different shapes, one being circular the other rectangular.

The rectangular pit, Pit 1355, was located centrally in the structure and measured 3.6m long by 2.2m wide and 1m deep, with vertical sides and a flat base. The pit contained three deliberately dumped deposits and an alluvial clay layer near its base. Frequent pot, moderate bone, rare metal (including the shank of an iron nail) and lithic inclusions were noted among the dumps of material, which is suggestive of a waste disposal pit, although this is likely just its final utilisation. A piece of potentially architectural stone was also found. The presence of an alluvial layer as the secondary deposit of the pit may suggest that at the time of its construction this pit was open to the elements, and possible flooding may provide an explanation of the later addition of a shelter covering the surrounding area.

The circular pit, Pit 1330, was located near the north-eastern corner of the structure, with a diameter of 4.00m and a depth of 0.55m with rounded sides and base. This pit contained six naturally infilled deposits of possibly wind-blown material. Analysis of samples taken from the pit identified spelt and wheat in the fills, as well as part of a small iron object. Cereal grain from the basal fill of the pit (1331) was radiocarbon dated to cal AD 120-240 (SUERC-110272, 2). The structure and pits likely formed part of the initial phase of enclosure as a key part of the enclosure layout. Two similar circular pits were also noted within Enclosure 1 where they are thought to represent waterholes.

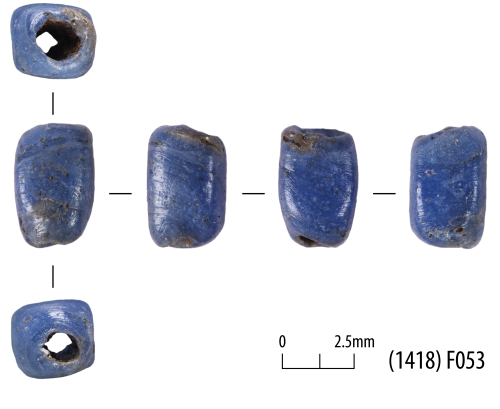

Structure 2 was located on the eastern side of Enclosure 7 and is similar in size to Structure 1 (12 x 8m), However, Structure 2 otherwise appeared to be of a more substantial construction with beam slots measuring 1.02-1.60m wide and 0.30-0.40 deep. A small contemporary slot, 1746, extending into the structure from its southern edge, would have subdivided the internal space. The northern edge was truncated, with several stratigraphically later pits cutting the structure. One of these, situated at the north-western corner of the structure, was found to contain a 3rd to 4th century cylindrical glass bead, suggesting an earlier date for the structure, possibly contemporary with Structure 1.

An area with significant artefactual material was noted at the south-eastern corner of Enclosure 4, adjacent to the northern limit of excavation (Figure 8). This material included a considerable quantity of 3rd to 4th century pottery, glass, and bone objects. The bone objects, which included a pin, a rough-out and working waste, and which were not identified anywhere else within the excavation area, are particularly indicative of industrial or craft activity. A number of features in this area also contained dumped and heat-affected material, which was completely absent from the other parts of the enclosure system. If industry was located in close proximity, as suspected, much of this material, which evidences more proactive human activity, could have made its way naturally into the ditches of this area.

Following the initial establishment of the enclosures, a period of expansion was noted that established four new enclosures to the east (Figure 9). The initial phase of expansion appeared to primarily overlie the earlier Enclosure 12. The rectilinear Enclosure 13 defined an area c. 47 x 44m, with two north to south aligned ditches creating an internal division with a 2.5m wide entranceway. The ditches may represent an initial phase of expansion with the entranceway aligned to the existing enclosure system before Enclosure 13 was defined. The ditches of this new enclosure, Enclosure 13, contained alluvial silt and clay deposits similar to those noted among the ditches of the initial enclosure system and contained artefactual remains of a similar date, indicating that, although stratigraphically later, this initial sub-phase formed part of the continuous development of the site. An articulated cattle radius recovered from the basal fill of the main enclosure ditch dates this expansion to cal AD 230-380 (SUERC-110491), which is contemporary with dates from the main enclosure system. The expansion potentially occurred within a century or so after the initial establishment of the enclosures in the west.

Enclosures 14 and 15 adjoined the south-eastern extent of Enclosure 13 and were far smaller in scale, reminiscent of those within the existing system. The ditches all contained a distinct sequence of deposits (Figure 10), which after a brief period of basal windblown material, consisted of distinct layers of grey-blue alluvial clays topped with a distinct layer of decomposed organic material. The presence of this organic material indicates that the ditches were left unmaintained for long enough at the time of deposition for plants to form a layer within the ditch, which were later buried beneath further alluvial silt deposits. This organic layer was also noted as a lower fill among some of the maintenance recuts in the west of site (detailed below), which may indicate a contemporary deposition period. However, with the exception of the organic band, the fill profile of the ditches is unique to this area of the site, possibly indicating a slight disparity in infilling periods or conditions between the areas.

The final phase of expansion was noted as a recut to the southern boundary of Enclosure 13, which continued to the east to expand Enclosure 15, creating a new sixteenth enclosure against the eastern boundary of the enclosure system. The expanded Enclosure 15 contained several deposits, shallow pits and gullies of unknown function, but which contained dark dumps of ash-like material. Finds from the features of Enclosure 15 were unfortunately undiagnostic, consisting primarily of small pot sherds, and are contemporary with the other Roman artefactual material recovered from elsewhere on the site.

| Enclosure | Sub-Phase | Area (Length x Width) |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | 1 | 48m x 35m |

| 2 | 48m x 43m | |

| 3 | 48m x 43m | |

| 14 | 2 | 15m x 15m |

| 15 | 2 | 12m x 16m |

| 3 | 22m x 30m | |

| 16 | 3 | 35m x 26m |

Although ongoing maintenance was noted among the fills of all enclosure ditches, a more extensive period of maintenance and reorganisation was also recorded, evident across the enclosure system. The primary function of these recuts appears to have been to re-establish specific sections, as they were often noted terminating part-way along the earlier ditches. This may have been due to an increased level of alluvial deposition, possibly as a result of their proximity to the edge of the roddon, and probable wet ground. Alternatively, it is possible that agricultural activity during this period was focused more specifically in these areas and had moved away from the activity in the north. Certainly, the entrances to Enclosures 6 and 9 appeared to be closed by the recuts, and the nature of the trackway to the south-west had also changed with the removal of the ditch along its southern edge.

No direct stratigraphic relationships were recorded between the maintenance activities in the west and the expansion of the enclosure system to the east, and as such these activities may be broadly contemporary. The dates of the artefactual remains from both periods range between the 1st and 4th centuries AD. However, the distinct sequence of deposits noted among the ditches of the eastern enclosures, which was not observed in the western recuts, suggests that infilling of the ditches occurred at different times. The radiocarbon dates from the maintenance activity dated the recuts to cal AD 250-420 (SUERC-110283) and cal AD 430-580 (SUERC-110286), indicating that this activity may post-date the other Roman activity on the site, with the ditches possibly remaining open or at least visible into the early Anglo-Saxon period.

Despite late radiocarbon dates gathered from the maintenance phase, no activity was identified on site that could be definitively dated to the early Anglo-Saxon period. However, this does not preclude the possibility that activity continued through this period. Anglo-Saxon Enclosure 1, for example, was located in an otherwise empty space between the datable Roman and mid-Saxon activity and contained no datable material. Its form also does not adhere to the patterns of enclosure activity seen on the site in either the Roman or mid-Anglo-Saxon periods, being rectilinear in plan but considerably narrower and shallower than the Roman enclosures. Additionally, the stratigraphically earliest sub-phases of activity associated with the mid-Saxon enclosures were also undated by either artefactual material or by radiocarbon dating, and may represent small-scale transitional activity. Furthermore, it is possible that the distinct lack of early Anglo-Saxon artefactual material indicates continuity in the use of existing late Roman wares by the local population beyond the end of the Roman period rather than the abrupt abandonment of a well-established agricultural landscape in AD 410.

The mid-Anglo-Saxon activity at Viking link was situated both to the east and west of the Roman farmstead and consisted of enclosures and open field systems respectively (Figure 11). Very little interaction was noted between these activities and the Roman settlement. It is unclear why this is the case, as it is probable that space was limited on the higher ground of the roddon. The two most likely explanations for the distinctly separate stratigraphies of the two periods are that either the water level of the Fens had risen during this period, making reutilisation of the Roman enclosure system difficult to impossible or, conversely, that the system was still largely visible in the landscape and therefore avoidable. If the system did continue to exist within the landscape it is probable that for some reason it was not considered fit for the agricultural practices being employed during the Anglo-Saxon period.

In addition to the undated Anglo-Saxon Enclosure 1, four enclosure spaces were located in the east of excavation area SMR 6 (Figures. 12 and 13), stretching over an area 180m in length and which started c. 60m south-west of the Roman boundaries. These enclosures were broadly oval or sub-oval in plan and consisted of multiple sub-phases of ditch activity. These sub-phases may represent seasonal establishment of the enclosure spaces, often being utilised for as little as a single season, rather than becoming a permanent fixture in the landscape.

Enclosure 2 was the westernmost of the enclosures, and its associated ditches covered a total space of c. 47m x 29m. The enclosure was defined by ditches 4297 and 4901, the latter being recut by Ditch 4382. A number of short ditch sections crossed the interior, potentially representing sub-divisions or multiple phases of development. A charcoal sample date gathered from one such ditch, Ditch 4904, returned a date of cal AD 650-780 (SUERC-110274).

The strip of land immediately to the west of this enclosure, Midden areas 1-3, contained a number of features rich in dumped deposits of probable waste material (Figure 14). This material included some of the best-preserved cereal grain recovered from the site, which returned radiocarbon dates between cal AD 660 -950 (SUERC-110276, SUERC-110275, SUERC-110281). A date from a cattle tooth was also recovered (cal AD 660-780; SUERC-110291). The cereal grain assemblage from these features included bread/club/rivet wheat, and hulled straight barley grains with silicified plant macro-remains recovered from the pits of Midden 2, suggesting they have been exposed to heat.

The area of Enclosure 3 measured 28m x 27m with multiple phases of development noted prior to the establishment of the enclosure ditch, Ditch 4911 (Figure 15). A cattle skull from the basal fill of Ditch 4911 was radiocarbon dated to cal AD 650-780 (SUERC-110292). Enclosure 3 was U-shaped with a south-facing opening. Further adjoining boundaries extended to the north and to the south where Ditch 4819 may have formed a continuation separating Enclosure 3 from a series of pits.

Pit 4624 (Midden 4) was sub-circular in plan and measured 7.40m x 5.04m x 0.40m. It contained a series of naturally infilled deposits from which no artefacts were recovered. This was cut by an irregularly shaped feature 4820 (Midden 5) which measured 9.4m x 2.30-3.00m x 0.88-1.20m and contained pottery and animal bone. Ditch 4873 cut Midden 4 and continued as Ditch 4873 to cut Enclosure 3. Charcoal from the top fill of this ditch was radiocarbon dated to cal AD 670-880 (SUERC-110277), potentially indicating a similar date for much of the activity associated with and surrounding Enclosure 3.

A group of linear ditches define the stratigraphically earliest phase of activity in this area underlying Enclosure 4. The ditches, 4928, 4826, 4825 and 4868, were similar in dimensions and contain sterile fills. These were truncated by a series of curvilinear ditches, which were in turn were truncated by curved ditches extending to the south and adjoining a north-west to south-east aligned ditch, Ditch 4827. Samples of cereal grain and chicken bone from the basal fill of Ditch 4871 forming part of this sequence were radiocarbon dated to cal AD 670-780 (SUERC-110293) and cal AD 770-980 (SUERC-110282). This sequence is truncated by the ditch defining Enclosure 4, Ditch 4932, which like Enclosure 3 was U-shaped but with a north-facing opening. The enclosure surrounds a space measuring 23m x 26m.

Boundary 1 was located between enclosures 3 and 4 running for 30m from the southern limit of excavation to the south-eastern corner of Enclosure 3. Activity at enclosures 2-4 appears to be defined by Boundary 2, which extends across the excavated area. Boundary 2 extended for c. 60m and measured 1.10-1.3m x 0.43-0.52m with fills of greyish-brown clayey-silt. Boundary 2 truncated part of the latest ditch of Enclosure 4. This ditch aligns with Boundary 3 at the eastern extent at the site, which extends for 22.8m, and was similar in form and dimensions. Boundary 4 may extend between these although no relationship could be identified. The space between boundaries 2 and 3 contained comparatively sparse archaeology. It is possible that it represents a transitional enclosure, between the use of the ovular enclosure system and its extension into rectilinear spaces.

A very large boundary ditch (S5) was also noted in this area located 48m to the east of Enclosure 4. This ditch measured 70m long by 3.5m wide and was over 1m deep (its base unreachable owing to safety concerns). The southern portion of this ditch was orientated north-north-east to south-south-west, and turned to the north-west halfway along its length. This alignment is not consistent with any of the other ditches or enclosures recorded within the excavation area. The extreme size and depth of this ditch, compared with the other archaeology from the site, appears to indicate that it functioned as a more permanent division of the landscape, perhaps as the final eastern boundary to the activity.

The final curvilinear enclosure, Enclosure 5, was defined by a ditch that extended for c. 63m and measured 0.95-1.08m x 0.10-0.45m. The ditch is comparable to those of the other enclosures and truncates Boundary 5, suggesting it forms part of the main phase of activity.

The complex sub phasing of the ditches of Anglo-Saxon enclosures 2, 3 and 4 are all indicative of the short-lived or temporary nature of the activity that took place in this area of the site. The evidence from Viking Link is likely to represent seasonal use and disuse of enclosures in order to graze cattle. Evidence from the zooarchaeological assemblage is also consistent with these enclosures being for livestock, likely a herd of dairy cattle.

Unlike the eastern Anglo-Saxon activity, the western activity did not constitute obviously enclosed spaces as its signature. Instead, it comprised a number of thin linear boundaries, largely orientated north-west to south-east and north-east to south-west (Figures. 16 and 17). These boundaries have been interpreted as the small divisions of an open field system, possibly to indicate furlongs within the field. No Anglo-Saxon artefactual remains were recovered from this area of the site, with instead only a very small amount of residual Roman wares identified. The archaeobotanical and archaeozoological assemblages from this area were also extremely limited indicating the possibility of more arable, rather than pastoral, land use in this area. It is also probable that the ditches of this area were not utilised for long enough for significant quantities of material to accumulate within them, as the majority do not exhibit any obvious evidence of maintenance over time.

Four small rectangular enclosures were identified in this area of the site. The first constitutes the only supposed Anglo-Saxon archaeology that had any stratigraphic relationship with the Roman enclosure system. This was located against the northern limit of excavation, just to the west of the intercutting area of industrial activity. It enclosed a space of 12 x 10m and contained largely sterile fills, with any earlier artefactual remains recovered probably resulting from the disturbance of the earlier archaeology. This small enclosure not only truncated the ditches of the Roman enclosures in the area but also a number of small plough lines, indicating that between the cessation of the Roman activity and the establishment of the enclosure the area was under plough.

The remaining three enclosures were all situated in the south-westernmost corner of site (Figure 18), on the roddon situated on the other side of the area of lower, wetter, ground. These three enclosures all measured between 8-11m wide by 11-15m long and were orientated broadly north to south. The westernmost of these exhibited an earlier, less rectangular, phase where the enclosure had been larger (16m wide by 24m long). A cattle molar from this earlier phase was dated to cal AD 770-950 (SUERC-110287), which might indicate that this activity was contemporary with the later sub-phases of Anglo-Saxon enclosure in the east. The exact function of these enclosures is unclear; however, it is possible that they are the result of temporary pens for livestock.

The final activity noted at Viking Link consisted of post-medieval field boundaries. These boundaries crossed the site on a north-north-east to south-south-west alignment and truncated all earlier activity (Figure 19). The majority were unexcavated during the project as they contained obviously modern infills of brick and rubble and were extant on the first edition Ordnance Survey maps of the area, dating to 1888.

However, some smaller, post-medieval enclosures were also noted. One was situated to the north of the Roman expansion activity, while a small system was also located truncating the eastern Anglo-Saxon enclosures. The northerly enclosure produced Bourne D Ware pottery dating to between the 15th and 17th centuries, while the eastern system contained an early to mid-18th century bowl base. Unlike the Roman and Anglo-Saxon activity, which relates to small-scale pastoral agriculture, these post-medieval ditches predominantly relate to the large-scale reclamation of the Fens that took place in earnest in the 18th century.

Roman pottery | Anglo-Saxon pottery | Organic residue analysis | Glassware | Worked bone | Metalwork | Metallurgy | The worked stone

The finds from Viking link include pottery from the Roman and early medieval period as well as small quantities of metalwork, worked animal bone, glassware and worked stone. The find categories are addressed by individual specialists below, with supporting data provided in Appendix 1. Full specialist reports including methodologies are available in the physical site archive.

| Row Labels | Count | Weight (g) | MNV | EVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0. Earlier Boundaries | 29 | 326 | 10 | 0.27 |

| 2. Expansion | 140 | 2400 | 48 | 2.27 |

| 3. Maintenance | 167 | 3652 | 72 | 2.31 |

| 4. Later Developments | 8 | 146 | 6 | 0.08 |

| 1. Establishing Enclosure | 511 | 6182 | 183 | 6.4 |

| 5. Roman Unphased | 19 | 300 | 8 | 0.41 |

| 9. Unstrat | 34 | 656 | 18 | 0.35 |

| 7. Activity to the south-west | 12 | 409 | 8 | 0.17 |

| 6. Anglo-Saxon (east) | 8 | 168 | 8 | 0 |

| 8. Post-medieval | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Grand Total | 929 | 14240 | 362 | 12.26 |

The Viking Link excavations recovered a total of 929 sherds (14.240kg) of Roman pottery with a mean sherd weight of 15.32g. The material exhibits slight to severe abrasion, with the majority only moderately abraded. The assemblage represents a minimum of 362 vessels. There is a high incidence of undiagnostic body sherds, reflected in the relatively low EVE of 12.26 for an assemblage of this size. The assemblage is associated with Roman and Anglo-Saxon settlement features, with material recovered from ten Roman and four middle Saxon phases (Table 4). Within these phases, the pottery can be assigned to feature groups as described below. Decoration is rare in the assemblage, recorded on only 35 sherds.

| Ware Type | Fabric Code (CLAU) | NRFRC | Fabric description | Ct | %Ct | Wgt (g) | % Wgt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPH | DR20 | BAT AM1/2 | Dressel 20 amphorae | 1 | 0.11% | 327 | 2.30% |

| FINE | CC | Other colour-coated wares | 7 | 0.75% | 166 | 1.17% | |

| FINE | NVCC | LNV CC | Lower Nene Valley colour-coated ware | 140 | 15.07% | 2086 | 14.65% |

| LFINE | SPCC | SWN CC | Swanpool colour-coated ware | 2 | 0.22% | 32 | 0.22% |

| MLCO | DWSH | DAL SH | Dales ware; late shell-tempered; | 167 | 17.98% | 2079 | 14.60% |

| MORT | MOMH | MAH WH | Mancetter Hartshill mortaria | 1 | 0.11% | 30 | 0.21% |

| MORT | MONV | LNV WH | Lower Nene Valley mortaria | 7 | 0.75% | 508 | 3.57% |

| MORT | MORT | Mortaria - undifferentiated | 1 | 0.11% | 18 | 0.13% | |

| OXID | CR | Miscellaneous creamware | 1 | 0.11% | 6 | 0.04% | |

| OXID | OX | Miscellaneous oxidised ware | 4 | 0.43% | 37 | 0.26% | |

| OXID | OXWS | Oxidised with white slip | 2 | 0.22% | 5 | 0.04% | |

| REDU | BB1 | DOR BB1 | Black-burnished 1 | 1 | 0.11% | 14 | 0.10% |

| REDU | BB2 | Black-burnished 2 | 9 | 0.97% | 254 | 1.78% | |

| REDU | COAR | Miscellaneous coarse wares | 22 | 2.37% | 96 | 0.67% | |

| REDU | GREY | Miscellaneous grey wares | 462 | 49.73% | 7113 | 49.95% | |

| REDU | NVGW | LNV GW | Lower Nene Valley greyware | 65 | 7.00% | 1058 | 7.43% |

| SAM | SAMCG | LEZ SA2 | Central Gaulish Samian | 1 | 0.11% | 8 | 0.06% |

| SAM | SAMCG-EG | Central or East Gaulish Samian | 1 | 0.11% | 3 | 0.02% | |

| SAM | SAMSG | South Gaulish Samian | 3 | 0.32% | 50 | 0.35% | |

| SHEL | SHEL | Miscellaneous undifferentiated shell-tempered | 32 | 3.44% | 350 | 2.46% | |

| TOTAL | 929 | 14240 |

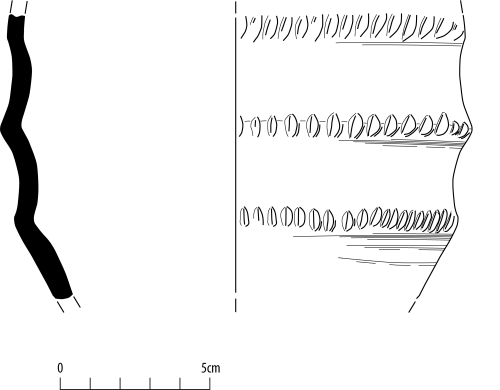

The assemblage is dominated by GREY, ubiquitous locally produced sandy grey wares (Table 5). These account for 50.0% of the assemblage by weight and 49.7% by count, meaning that the majority of the assemblage can only be broadly dated to the Roman period. Where fabric or form is distinctive, it has been possible to assign some GREY sherds to the production centres at Rookery Lane or Swanpool, giving a 3rd to 4th century date for these (see catalogue). The range of forms in the GREY assemblage is limited, with examples of bowls, dishes and jars noted, with jars dominating. Jars are further categorised by rim shape. Bowls include examples of flanged bowls of varying sizes. Two sherds of a tazza recovered from Ditch 1796 [Enclosure 7, North) are of particular interest in the GREY assemblage. The sherds are hard-fired and highly burnished. They feature three raised areas around the vessel, which have been notched (Figures 20 and 21). Tazze typically have a pedestal base and are usually associated with burning incense (Davies et al. 1994), and some have ritual associations, with examples associated with burial and cremations at other sites. Tazze are found in both frilled and notched forms, with notched said to be later than frilled, and tending to replace the latter in the 3rd and 4th centuries (Grimes 1930, 169). Tazza were among the corpus of forms produced at the pottery production centre at Market Rasen (Darling 2005). A notched example in an oxidised ware, of similar shape and form to the Viking Link example, was recorded at Colchester (Symonds and Wade 1999, form 724). Notched decoration is also present on an example from Elms Farm, Essex (Biddulph et al. 2015). Notched decoration is noted on jars from the kiln site at Swanpool (Webster and Booth 1947, 70).

A range of decorative techniques were noted within the GREY assemblage, including burnished wavy lines and burnished lattice. Of note is the example of linear rusticated decoration, recorded on body sherds derived from two vessels (2 sherds, 16g Ditch1401, Trackway; 5 sherds, 39g, Ditch 3159, Later developments). This type of decoration has been noted to be geographically characteristic as well as closely dated. The linear rustication is typically found north of a line running from the head of the Severn Estuary to East Anglia (Lee et al. 1994, 17). While found on pre-Flavian sites, it is especially prevalent on Flavian sites, continuing into the Trajanic period with the end of the tradition typically given as AD 130 (Thompson 1958, 21). The production of these wares at North Hykeham has been dated to the Flavian period. These sherds, if originating from North Hykeham, would represent some of the earliest material in the assemblage. A number of sherds with double incised lines around the shoulder have been recorded and may well have derived from rusticated vessels where it is used to delineate the area of rustication (Thompson 1958, 26). Decoration on five vessels was recorded where both the fabric and decorative techniques are consistent with products from the kiln at Swanpool (Webster and Booth 1947).

Other reduced wares include 65 sherds (1058g) of Lower Nene Valley greyware (NVGW). These diagnostic forms include dishes with plain rims, these being the most common NVGW dish form in the 3rd century (Perrin 1999, 86). The examples were recorded from Ditch 1745 (Structure 2) and Ditch 1796 (Enclosure 7, North) and Ditch 1797 (area of craft and industry). There is a small assemblage of black-burnished wares, along with miscellaneous coarse wares.

Oxidised wares are rare, comprising only seven undiagnostic body sherds (48g). Shell-tempered wares are dominated by local fabric, Dales ware (DWSH), which accounts for 14.6% of the assemblage by weight, 18.0% by count. Dales Ware is dated from AD 230-370 by Gillam (1951, 160) although, its presence has been recorded form as early as AD 200 elsewhere (Darling and Precious 2014, 83) who note the earliest presence in Lincoln from the 3rd century onwards. The Dales Ware assemblage comprises in the main the classic Dales ware jar form (JDW), along with single examples of a bowl with expanded rim (BEXR) and a lid. In Lincoln assemblages, Dales Ware lids are rare and are generally dated to the mid-late 4th century (Darling and Precious 2014, 88); the Viking Link example was unstratified. There are a further 32 sherds (350g) of miscellaneous shell-tempered wares.

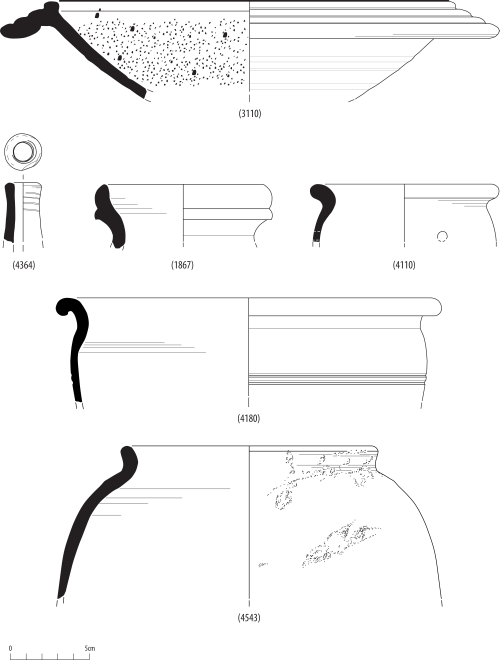

Amphorae are represented by a single body sherd recovered from Ditch 1342 (Enclosure 7, East, Maintenance). The sherd is in fabric DR20, of Baetican origin and likely derived from a Dressel 20. There is a small assemblage of mortarium, comprising nine sherds with a total weight of 556g, representing a minimum of 6 vessels. The majority of the mortarium can be identified as deriving from the Lower Nene Valley (MONV) including a large fragment of reed-rimmed mortaria with the typical slag-based trituration grits, recorded from Ditch Group 3273 (Figure 22). This is an example of a Perrin M19 (1999, 129), typologically dated to the 3rd century. The other diagnostic MONV example, from Ditch 1796 (Enclosure 7, North), is a Perrin-type M36 (1999, 132), typologically later 3rd to 4th century in date. The only other diagnostic mortaria is an example of a hooked flange type mortarium, from Mancetter Hartshill (MOMH). This type is noted in Lincoln assemblages from the early to mid-3rd century, also recovered from Ditch 1796 (Enclosure 7, North).

Fine wares are dominated by Lower Nene Valley colour-coated wares (NVCC; Table 5), accounting for 14.6% of the assemblage (by weight). The assemblage is dominated by dishes and bowls, with examples of dishes with plain upright rims (DPRS) being the most common. This form, Perrin 231-235, was produced from the later 2nd century onwards though most are typically of 4th-century date (Perrin 1999, 101). The examples in the assemblage were recovered from features dating to the establishment of the enclosures along with some unstratified examples. Also common were dishes with rounded rims, NVCC copies of NVGW (Lower Nene Valley greyware forms), with a production date range the same as for the DPRS. All examples of these were recorded from the initial phase of enclosure. There is also a range of forms in the NVCC assemblage imitating Samian vessels. Two examples of both B18/31 and B36 were noted, along with single examples of B31, B36 and B37. The main period of production for samian imitation vessels at Nene Valley was the mid-later 3rd century to the early 4th century (Perrin 1999, 102). Such imitations were also being produced at the same time by both the New Forest (Fulford 1975, types 61-3) and Oxfordshire (Young 1977 , types 44-53) industries. The initiation samian vessels at Viking Link were recorded from throughout the Roman phase, with an imitation type 36 (B36) recorded from Ditch 1796 (Enclosure 7, North). One unusual sherd, in the form of a very narrow neck of a jar, was recorded from Pit 4362 within SMR6 and is likely residual (Figure 23). This sherd derived from a narrow-necked jar, Perrin type 191 (1999, 94) and is an unusual form, dating to the later 3rd to 4th century. As with the assemblage as a whole, decoration is rare on the NVCC assemblage, with only two examples of rouletted decoration noted. One is on a small fragment of beaker recorded from the topsoil and the other on a hemispherical bowl from Ditch 1126 (Enclosure 13, Expansion). The fine wares also included two sherds of Swanpool colour-coated ware (SPCC), comprising a rim and body sherd derived from a hemispherical bowl (BHEM) recovered from Ditch 1342 (Enclosure 7, East, Maintenance). Seven sherds of undiagnostic colour-coated wares were also recorded.

Imported wares comprise solely samian wares, present in both Central and Southern Gaulish fabrics. The assemblage consists of 5 sherds with a total weight of 61g. The assemblage includes a small rim sherd of a Curle 23 (Webster 1996, 67) derived typically from a cup and dish 'set'. These forms were made in the late Flavian period with East Gaulish examples imported up to the mid-3rd century. The Viking Link example derived from Ditch 1791 (area of craft and industry). This example has been burnt, making it difficult to determine the fabric more accurately. The remainder of the samian is undiagnostic in form; however, a sherd from Pit 4178 (Roman-unphased) of La Graufesenque origin was noted to have a partial repair hole present to the edge of the sherd.

An assemblage of 917 sherds with a total weight of 13.995kg of Roman pottery was recovered from features within areas SPE1 and SPE2, with pottery recorded from features that overlap between the two areas. The assemblage equates to a minimum of 351 vessels with an EVE of 12.26. The assemblage is discussed below by key phase.

A total of 29 sherds (326g) of Roman pottery was recovered from features associated with the earlier boundaries. Of these 15 sherds, weighing only 24g, were from Sample 068 taken from Ditch Group 1620. The remainder of the material was recovered from Ditch Group 1793. The assemblage equates to a minimum of 10 vessels with an EVE of 0.27. The assemblage comprises grey wares (GREY) along with shell-tempered pottery of Dales Ware (DWSH) and other miscellaneous shelly fabrics (SHEL). They were largely undiagnostic in terms of form, with examples of flanged bowls and jars noted.

An overall total of 511 sherds (6182g) of Roman pottery was recovered from ditches, pits and structures assigned to the establishment of the enclosure system. The assemblage equates to a minimum of 183 vessels with an EVE of 6.4. This is the largest phased assemblage in terms of sherd count. It mainly comprises reduced wares (GREY; BB2; COAR) along with shell-tempered wares. The Nene Valley wares are present in colour-coated, greywares and mortaria, along with the only example of Mancetter-Hartshill mortaria. This material included an assemblage from Ditch Group 1796 comprising 125 sherds weighing 1666g. This included a large assemblage, 26 sherds (346g), of Nene Valley colour-coated wares, along with 55 sherds (748g) of GREY and 30 sherds of DWSH. This assemblage included the tazza (see above). Ditch Group 1454 contained 60 sherds with a total weight of 808g, comprising in the main greyware (GREY). Ditch Group 1413 contained 16 sherds (219g).

Area of craft and industry

The assemblage includes a total of 200 sherds (2049g) of Roman pottery recovered from features located in the north-eastern corner of Enclosure 7 and south-eastern corner of Enclosure 4, associated with craft production. In terms of fabrics, the assemblage is similar in composition to that recorded from the enclosure system, with an absence of mortarium. The two most common fabrics are again GREY and NVCC. The largest assemblage from this area derived from Ditch 1797 that extended south from the northern limit of excavation, and comprised 146 sherds (1721g), the composition of which reflects the composition of the whole area. Other ditch groups contained smaller assemblages (Ditch 1364-6 sherds, 78g; Ditch 1791-2 sherds, 9g; Ditch 1794-14 sherds, 30g; Ditch 1795-5 sherds, 24g). An assemblage of 27 sherds (187g) was recorded from ditches 1799 and 1792. This comprised greyware (GREY), Dales ware (DWSH) and Nene Valley colour-coated wares (NVCC). The assemblage comprised solely undiagnostic body sherds.

Trackway

An assemblage of 15 sherds with a total weight of 205g was recorded from the trackway ditches. This represents a minimum of 12 vessels, with EVE of 0.03. As reflected by the EVE measurement, the majority of the sherds were undiagnostic body sherds, with GREY fabrics representing 14 sherds (125g). Ditch1401 (Northern Trackway Ditch, North-east) contained a total of 13 sherds (195g) while two sherds of Nene Valley greyware came from Ditch 1902 (Southern Trackway Ditch).

A total of 140 sherds (2400g) of Roman pottery was recovered from features associated with the expansion of the enclosure system. The assemblage equates to a minimum of 48 vessels with an EVE of 2.27. The assemblage is comprised of just four fabrics, with DWSH and GREY dominating. The diagnostic forms are jars, along with a single example of a BB-type flanged bowl in GREY. The largest assemblage was recovered from Ditch 1126 (Enclosure 6), 24 sherds weighing 952g. The assemblage comprised GREY and NVCC fabrics. The Nene valley ware comprises a dish with triangular rim, Perrin-type 217 (1999, 101) dating from the mid-2nd century onwards, and a rim sherd of a hemispherical bowl with rouletted decoration, potentially imitating a Samian Dr 37 form. The rouletted decoration resembles a Perrin-type 240 (1999, 102) dating from the later 3rd to early 4th century. The assemblage from Pit 4211 (Enclosure 15) includes fragments of the same vessel recovered from Ditch 4944 (see Unphased below).

This phase sees an increase in the volume of pottery as well as the range of fabrics present. The assemblage totals 167 sherds weighing 3652g and was recovered from ditches dated to this phase of the settlement. This equates to a minimum of 72 vessels with EVE of 2.31, again representative of the lack of rim sherds in the assemblage. All the pottery was recovered from ditches, with a large assemblage recovered from Ditch 1342 (Enclosure 7, East). This assemblage included a range of fabrics, including a single body sherd of central Gaulish samian ware and the only sherd of amphorae from the site.

An assemblage of 26 sherds (562g) of Roman pottery was recovered from Ditch 2026, which is the primary recut of the main enclosure system. The assemblage equates to a minimum of 17 vessels with an EVE of 0.625. The assemblage comprises Nene Valley wares both colour-coated (NVCC) and greywares (NVGW), Dales Ware (DWSH) and GREY reduced wares. The colour-coated wares are largely undiagnostic, including a sherd of a hemispherical bowl. The GREY wares include sherds of possible Rookery Lane origin (Webster 1960). This includes the partial rim of a collared-rim jar (Figure 24), akin to Darling and Precious type-1022-6 (2014, fig. 106), albeit without the notched decoration. Forms of this type were produced at both Swanpool (Webster and Booth 1947) and Rookery Lane (Webster 1960), though could equally have been the product of a more local production centre.

A small assemblage, five sherds (43g), was recorded from Ditch 1321, which cuts the Roman ditches within the area of craft activities. The ditch is comparable in form to those across the Anglo-Saxon area of activity. The assemblage comprised three sherds of greyware (GREY) along with single sherds of coarse ware (COAR) and Nene Valley colour-coated ware (NVCC). The only diagnostic sherd was a rim fragment from a NVCC bowl with triangular rim, dating from the mid-2nd century onwards.

A single sherd of GREY pottery was recovered from Ditch 1698, which also cuts the Roman enclosure system. It is a heavily abraded partial base, undiagnostic in form. A further two sherds were recovered from Ditch 1406.

A further 19 sherds, 300g, were recorded from unphased Roman features. Within this assemblage were two sherds of small jars, both with post-firing perforations to the shoulder. One recorded from Ditch 4944 exhibits a burnt residue to the exterior (Figure 25) and is part of the same vessel from Pit Group 4211. The other is a curved rim jar, of Darling and Precious type-985-7 (2014, fig. 104) with a suspension hole and double incised lines below the shoulder (Figure 26).

A total of four sherds (77g) of Roman pottery was recovered from features within area SMR1. The assemblage equates to a minimum of three vessels. All were undiagnostic body sherds with no rims present. Two fabrics were present in the assemblage, two sherds of Oxford white-slipped ware (OXWS) and two sherds of greyware (GREY), the larger of the GREY sherds was recovered from Ditch [3156], it has a fabric characteristic of the products from Rookery Lane. All the pottery was recovered from features associated with peripheral activity. The fabrics indicate a 3rd-4th century date for the material.

The assemblage from SMR6 is small (8 sherds; 168g) and largely undiagnostic, with the majority dating broadly to the Roman period. The diagnostic fabrics indicate a date range from AD 170, with an example of a 3rd-century form in NVCC. All the Roman pottery from this area was recovered from features dated to the middle Saxon period and therefore can be considered residual in these features.

The peaks of activity are shown to be in the initial phase of establishing the enclosure and in the maintenance. The pottery dates almost exclusively from AD 200 onwards. The composition of the assemblage is generally consistent across all the Roman phases of activity (Figure 28). Shell-gritted ware present were mostly represented by Dales Ware jars, with a few sherds of miscellaneous shell-tempered fabrics.

The range of fabrics, dominated by greyware and Dales ware, with small quantities of table ware, is comparable with that from Stallingborough (Rowlandson 2011). From the later 2nd century, the coarse wares are not easily attributed to a kiln or kiln group, with greyware production known from a number of sites in the vicinity of the city of Lincoln, namely Lincoln recourse (Corder 1950), Rookery Lane (Webster 1960), Swanpool (Webster and Booth 1947), Torksey, Little London and Knaith. With similarities in fabrics, it is often the forms that are relied upon to determine the origin of vessels. However, it should also be considered that the greywares could have been made at kiln sites more local to the site at Viking Link. The presence of samian, finer greywares, and colour-coated wares, which would have functioned as table wares, suggest domestic activity at the site. The tazza, as discussed above, is suggestive of ritual activity.

Romano-British fine wares, mostly Lower Nene Valley colour-coated wares, account for 16.04% of the assemblage by both weight and count. Samian ware is rare, representing less than 0.5% of the assemblage, demonstrating that much of the activity at the site is focused in the decades after the cessation of the importation of samian ware in the mid-3rd century AD. The Nene Valley wares represent a pattern of regional trade commencing in the mid/late 2nd century.

This proportion of fine wares, including Nene Valley wares, is comparable to the assemblage from Triton Knoll-SMR06 (Rowlandson 2020), though lacking the imported wares seen in the Triton assemblage, where they are assumed to be a result of maritime connections. The assemblage has affinities with that from both Lincoln (Darling and Precious 2014) and Old Sleaford (Elsdon et al. 1997), with coarse grey and shell-tempered wares dominating, supplemented by fine wares from the Nene Valley kilns. Similarly, the sites at Sutterton, located 8km to the east (Davies 1996; Precious 1996; Leary 2008) have assemblages, albeit small, of similar composition and date range. Nene Valley fine wares contributed a substantial proportion of the fine wares in the 3rd and 4th century at Old Sleaford (Elsdon et al. 1997) and Long Bennington (Leary 1994), where they are in the majority compared with Oxford and Swanpool products.

While 44 individual form types were recorded these can be broadly categorised into six groups, along with undiagnostic body sherds, which account for 24.03% of the assemblage by weight. The identified forms present are dominated by jars, accounting for 52.3% of the assemblage by weight.

Beakers are present only in the initial phases (Figure 29) of the enclosure while the only amphorae recorded is from the maintenance phases. Mortaria are present primarily in the initial phases of enclosure. A Mancetter-Hartshill example, dating from the early to mid-3rd century was recorded, along with a Lower Nene valley mortaria dating to the 3rd century. The mortaria are typical of regionally traded wares from the mid- to late Roman period in the area and consistent with consumption associated with small-scale domestic occupation.

Overall, the composition of the assemblage in both fabric and form suggests a settlement dating to the later Roman period, from the mid-2nd century AD onwards extending into the 4th century. The rusticated wares evidence some earlier settlement activity, while samian vessels can be curated for a prolonged period of time. The earlier sherds derived from earlier waste material incorporated into later features, along with the small assemblage of Iron Age pottery reported separately. The bulk of the Roman pottery is utilitarian in nature, comprising a range of jar and bowl forms, manufactured by local industries in reduced, and shell-tempered wares. The presence of a small assemblage of samian along with regionally traded colour-coated fine wares and mortaria suggests access to more refined wares to supplement the utilitarian vessels.

Post-Roman pottery totalling 730 sherds (3291g) from 33 contexts was recorded. Of these, 726 (3277g) were of early/mid-Anglo-Saxon date (Table 6), three were possibly medieval and one was undated. Early/middle Anglo-Saxon fabric groups have been characterised by major inclusions and pottery codes and date ranges follow the Lincolnshire Fabric CNames as far as possible.

| Fabric | CName | Date range | No | Wt/g | eve | MNV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglo-Saxon Shell-tempered fabrics | ESAXSH | 450-650 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Early Anglo-Saxon grog and mixed inclusions | ESGMI | 450-650 | 2 | 17 | 2 | |

| Early/mid Saxon fine sandy | ESFS | 450-800 | 25 | 653 | 0.05 | 3 |

| Early to mid Anglo-Saxon chaff-tempered ware | ECHAF | 450-800 | 2 | 5 | 1 | |

| Limestone-tempered Anglo-Saxon | LIMES | 450-850 | 8 | 98 | 5 | |

| Early to mid Anglo-Saxon greensand quartz | ESGS | 550-800 | 1 | 20 | 1 | |

| Early to mid Saxon sandstone-tempered | SST | 550-800 | 7 | 61 | 4 | |

| Iron-tempered fabrics | FE | 550-800 | 5 | 164 | 0.1 | 3 |

| Oolitic limestone-tempered fabrics | LIM | 550-800 | 11 | 232 | 0.12 | 5 |

| Southern Maxey-type ware | RMAX | 650-950 | 663 | 2020 | 0.62 | 25 |

| North Lincolnshire Oolitic Maxey-type | NLOMAX | 700-850 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |

| Totals | 726 | 3277 | 0.94 | 51 |

The estimated vessel equivalent of 0.94 is based on seven measurable rims; three other rim fragments could not be measured. Measurements of handmade vessels are always approximate unless a large proportion of the rim is present. For this reason, the minimum number of vessels (MNV), based on sherd families, was estimated for each context, producing a total MNV of 51 vessels.

Small quantities of early and early/mid-Anglo-Saxon handmade wares were recovered in a variety of fabrics, but the majority of vessels in the assemblage were Southern Maxey-type wares, based on the range of fossil shell inclusions (Spoerry 2016, 97). Other fabrics included examples dominated by quartz sand, limestone, sandstone or ferrous oxide, but most contained a background scatter of this range of inclusions.

The early Anglo-Saxon group included the rims of two jars, a bowl and two hanging vessels. Nineteen body and base sherds from Ditch 4541 (4543, Enclosure 3), in ESFS fabric with occasional sandstone, were part of a hump-shouldered globular vessel. A jar with a vertical flat-topped rim from the same context was in an oolitic fabric, as was a bowl with a vertical rim. Pit 4362, fill (4363), contained a small fragment of a flat-topped flaring rim from a jar, tempered with abundant (leached) fine limestone and sparse, coarse, rounded ferrous oxide. A globular hanging vessel with a vertical rim from Ditch 4823 (4665, Boundary 1) was in a silty fabric (recorded as ESFS), while another in a ferrous oxide fabric was globular with an inturned rim and was found in Ditch 4484 (4486, Midden 1); both had vertical pierced lugs. Four bases were present, two flat-angled, one flat with a rounded angle, and one rounded. No sherds were decorated.

Although large in terms of sherd count, the Maxey-type ware group included 618 sherds from Ditch 8117 (8118, Enclosure 4), which appeared to be largely from a single vessel, with perhaps one other also present, although the condition of the sherds made this impossible to ascertain. The main vessel in this context was another hanging vessel with an upright pierced lug. Unusually for this area and fabric, it appeared to have a thick Schlickung-like slip covering part of the body, although many areas of the outer surface were worn. This type of coarse slip is more commonly seen on early Saxon vessels in Essex and south Suffolk, so it is possible that the surface of this vessel was 'repaired' with the addition of a new layer of clay during its use. Other identifiable forms in this group comprised a possible bowl with a flat-topped beaded rim in Ditch 4908 (4369, Midden 1) (similar to a jar rim from Maxey; Addyman 1964, fig. 14.43), a thin-walled globular jar with a short squared-off vertical rim from Ditch 4871 (4783, Enclosure 4), and another jar with a vertical rim from Ditch 4908 (4369, Midden 1). The thin-walled vessel was associated with a radiocarbon date of 670-774 cal AD, and two other Maxey-type ware sherds from Ditch 4488 (4492, Midden 1) had an associated date of 772-944 cal AD. Bases included one sagging example and three flat.

One small body sherd (3g) of probable early medieval shelly-sandy ware (SSW) containing fine sand, coarse shell and ferrous oxide was found in Ditch 8097 (8098). Two abraded joining sherds (10g) of a jar rim of everted form with a flat-topped everted tip were found in Ditch 4541 (4605, Enclosure 3); the vessel was tempered with abundant (leached) shell (SHW) and had oxidised surfaces, and is likely to be of early to high medieval date. A tiny fragment (<1g) from bulk sample <812> in Ditch 8072 (8073, Enclosure 4) contained fine shell inclusions (SHW) but was otherwise undiagnostic.

A moderate quantity of Anglo-Saxon pottery was recovered, most of it from the fills of ditches (Table 7). The only large concentration of sherds (N=617) was in Ditch 8117 (8118), but as this group represented between one and three vessels it was comparable with quantities from other contexts across the site, none of which had an MNV greater than 3. This suggests that a thin scatter of rubbish, probably dispersed across the fields during manuring, was incorporated into the fills of the ditches when they were infilled. The overall average sherd weight for the assemblage is 4.5g, which is quite low for the fairly robust and thick-walled pottery produced in this period, although some relatively large sherds are also present.

| Fabric | 5R | 2MS | 3MS | 4MS | 5MS | U-MS | Un |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESAXSH | 1 | ||||||

| ESGMI | 1 | 1 | |||||

| ESFS | 1 | 2 | |||||

| ECHAF | 1 | ||||||

| LIMES | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ESGS | 1 | ||||||

| SST | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| FE | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| LIM | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| RMAX | 1 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |

| NLOMAX | 1 |

The range of fabrics in this assemblage is comparable with a group excavated at nearby Quarrington (c. 10km to the north-west), which was dominated by sandstone-tempered fabrics but also included oolitic, sandy and iron ore fabrics, as well as Southern Maxey-type ware (Young 2003 , table 2). One noteworthy difference, however, is that Ipswich ware did not occur at Donington. This ware has been found at Quadring and Gosberton, to the south of Donington (Blinkhorn 2012, 81-2), and given Donington's location on a Roman road and close to the Fen-edge, it would be expected here too, but perhaps its absence is due to the lack of settlement evidence within the excavated area. Also of interest is the presence of three vessels tempered with abundant red ferrous oxide, which Young notes tends to be more frequent to the east and north of Lincoln (Young 2003).

At least three vessels were in a relatively unusual 'hump-shouldered' form (cf. Myres 1977 , fig. 15), in ferrous, oolitic and sandy fabrics, which are most closely paralleled by examples from Norfolk and Yorkshire (Myres 1977, nos 1808 and 2344). Two were recovered from Ditch 4541 (4543, Enclosure 3, Figure 27) in the latest middle Saxon phase, and the ferrous-tempered one was from Pit 4362 (4364), which has an associated radiocarbon date of 677-877 cal AD, perhaps suggesting that this form was a relatively late development in the early Anglo-Saxon period.

Three hanging vessels were all from different site phases; an ESFS example from phase 2, an RMAX example from phase 4 and an FE one from phase 5. This type of vessel, with an upright lug on the rim, tends to be more common in the middle than the early Anglo-Saxon period, perhaps suggesting that activity on the site began towards the end of the latter period.

Lipids, the organic solvent-soluble components of living organisms, i.e. the fats, waxes and resins of the natural world, are the most frequently recovered compounds from archaeological contexts. They are resistant to decay and are likely to endure at their site of deposition, often for thousands of years, because of their inherent hydrophobicity, making them excellent candidates for use as biomarkers in archaeological research (Evershed 1993).

| Sample | Lipid Concentration | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Site | Context | Date | Vessel Type | μg g-1 | δ13C16:0 | δ13C18:0 | Δ13C | Attribution |

| VIK01 | SPE2 | 4180 | ROM | Necked jar | 7557.6 | -27.3 | -29.8 | -2.5 | Ruminant adipose |

| VIK02 | SMR6 | 4369 | SAX | Bowl with a flat-topped beaded rim | 2862.1 | -27.9 | -29.2 | -1.3 | Ruminant adipose |

| VIK03 | SMR6 | 4543 | SAX | ‘hump-shouldered’ form | 52.1 | -25.6 | -31.1 | -5.4 | Ruminant dairy |

| VIK06 | SMR6 | 8118 | SAX | Hanging vessel with an upright pierced lug | 1354.3 | -27 | -29.1 | -2.1 | Ruminant adipose |

| VIK07 | SPE1 | 1347 | ROM | Large JDW dales ware jar with flat rim | 1070.9 | -28.2 | -31.1 | -2.9 | Ruminant adipose |

| VIK08 | SMR6 | 4783 | SAX | Thin-walled globular jar with a short squared-off vertical rim | 18715.4 | -27.6 | -29.7 | -2.1 | Ruminant adipose |

| VIK09 | SPE2 | 1013 | SAX | Neckless ovoid jar | 660.1 | -28.2 | -33.2 | -5.1 | Ruminant dairy |

| VIK10 | SPE1 | 1409 | ROM | Everted rim jar | 335.4 | -28 | -31.6 | -3.7 | Ruminant dairy |

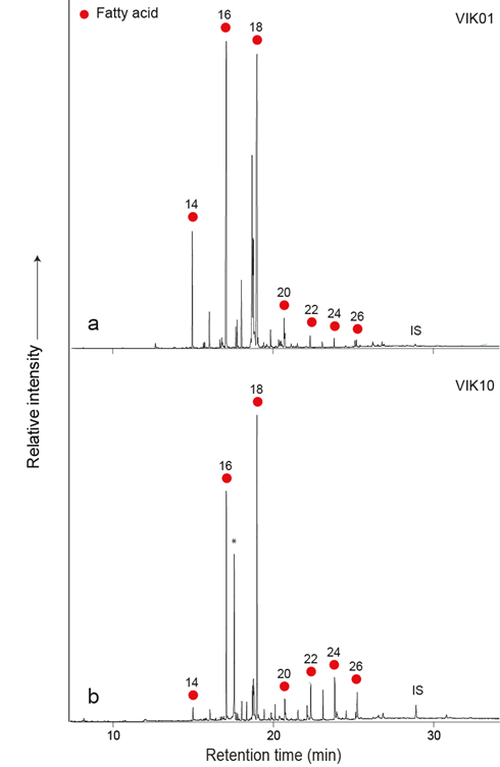

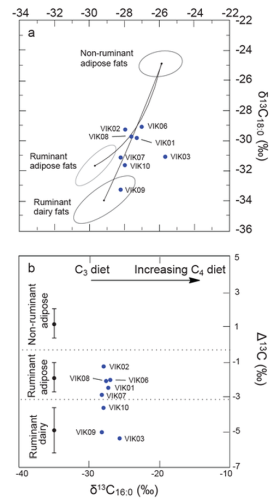

Lipid analysis and interpretations were performed using established protocols described in detail in earlier publications (Correa-Ascencio and Evershed 2014). Ten potsherds were analysed, with 8 sherds yielding interpretable lipid profiles (Table 8; Figures 30 and 31). The mean lipid concentration from all lipid-yielding sherds was 4.0 mg g-1, with a maximum lipid concentration of 18.7 mg g-1 (VIK08, IASHC ovoid/round-shouldered jar). A further four potsherds contained high concentrations of lipids (e.g. VIK01, 7.6 mg g-1, VIK02, 2.9 mg g-1, VIK06, 1.4 mg g-1 and VIK07, 1.0 mg g-1, comprising an IASH necked jar, IASH Oval jar, IASH jar(?) and Dales Ware jar, respectively), demonstrating excellent preservation. The lipid profiles were dominated by free fatty acids, palmitic (C16) and stearic (C18), typical of a degraded animal fat (Figures 30 and 31; Evershed et al. 1997a; Berstan et al. 2008).

Lipid recovery from the site was good at 80% with 8 of the 10 sherds yielding interpretable lipid profiles, and with many vessels containing extremely high concentrations of lipids, suggesting they were subjected to sustained use in the processing of high lipid-yielding commodities. Lipid recovery was comparable to that of Romano-British pottery from Hornsea Offshore Wind Farm Project, Lincolnshire, at 78%, and from two Iron Age/Romano-British sites in Lincolnshire (Goxhill and Immingham), which yielded similar lipid recovery rates at 86% and 85%, respectively (Dunne and Evershed, unpublished data).

Of the 8 lipid-yielding vessels (Table 8), three (38%) were used to process ruminant dairy products and five (62%) to process ruminant carcass products. Although a small dataset, these data are similar to those obtained from analysis of Romano-British pottery from the East Midlands Gateway site where four of the Romano-British vessels were used for dairy processing (25%), similarly suggesting dairying was of greater importance at this site in the Iron Age, reducing in the Roman period (Dunne and Evershed, unpublished data).

Although the Viking Links lipid results suggest that the processing of animal carcass fats was more important than dairying, this somewhat contrasts with the analysis of cooking pots from the site of Stanwick, where dairying seems to be an important component of the Romano-British economy (at 40% of vessels compared to 25% at EMG), at a level consistent with the preceding Iron Age population, although ruminant carcass product processing dominates at Faverdale (Copley et al. 2005; Cramp et al. 2011; 2012). However, it should be noted that dairy products may have been processed in different types of vessels (e.g. wooden bowls, animal skins). Furthermore, this is a small dataset.

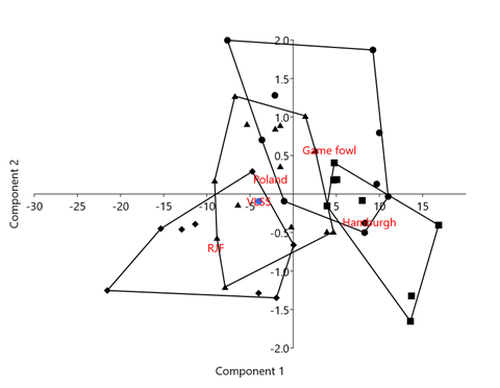

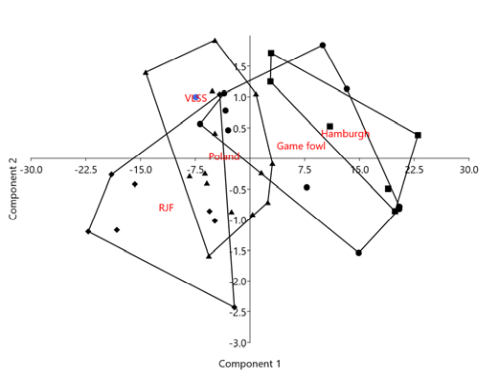

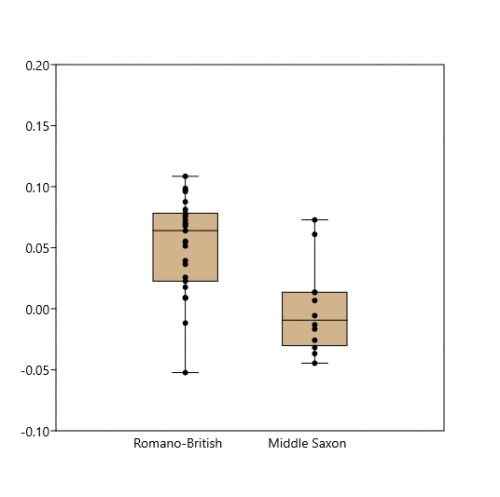

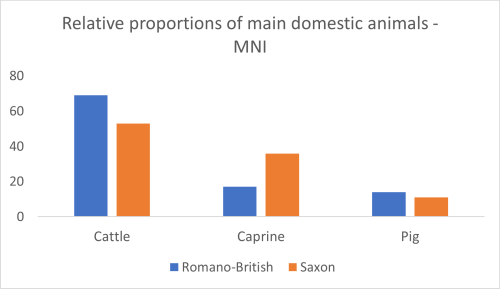

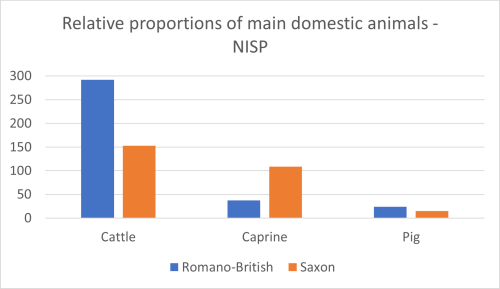

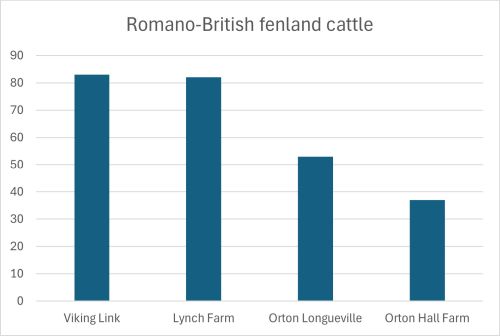

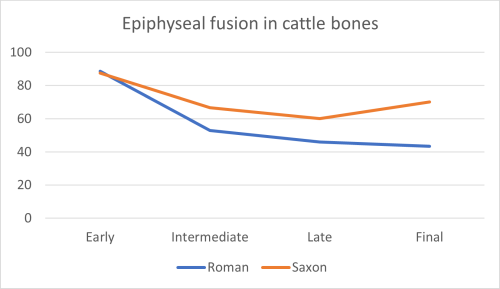

There is little evidence for non-ruminant (pig) product processing in the 8 lipid-yielding vessels from Viking Link vessels, although the site faunal data suggests the presence of pig in both the Roman and Saxon assemblages. However, it should also be noted that non-ruminant lipids could also originate from the processing of goose and domestic fowl (Colonese et al. 2017), whose faunal remains were identified at the site.