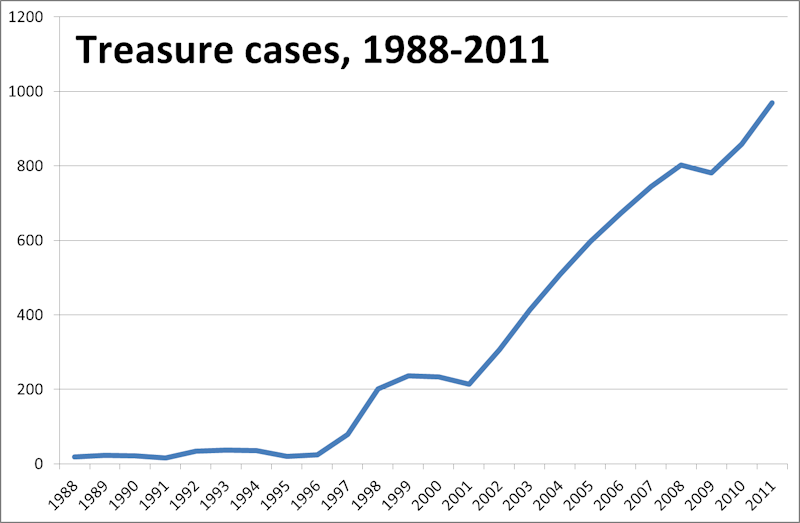

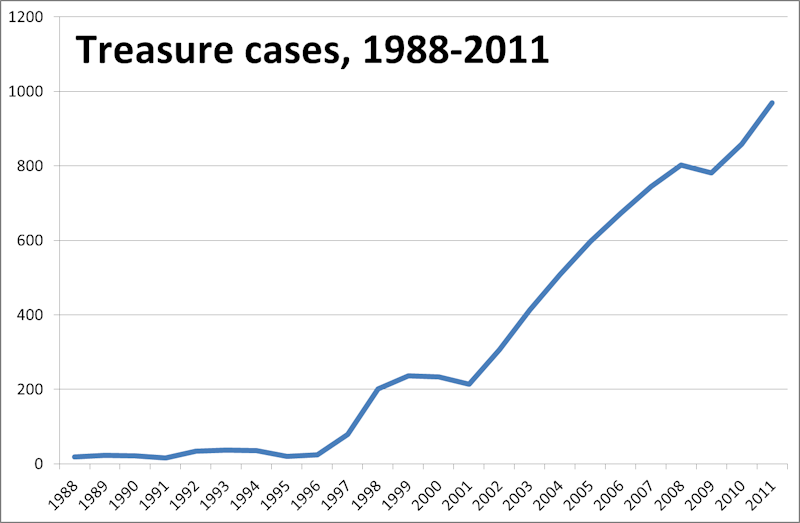

Figure 1: Finds reported as Treasure Trove (1988-97) and Treasure (since 1997) © British Museum

Keeper, Departments of Prehistory & Europe and Portable Antiquities & Treasure, British Museum

Cite this as: Bland, R. 2013 Response: the Treasure Act and Portable Antiquities Scheme, Internet Archaeology 33. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.33.8

This article provides a response to the other articles on metal detecting and archaeology in this issue of Internet Archaeology and provides a summary of the Treasure Act and Portable Antiquities Scheme in England and Wales.

The articles in this issue of Internet Archaeology present a wide range of responses to the issues raised by metal detecting. While the majority reflect the situation within the British Isles, we also have pieces from France and South Africa, reflecting the very different conditions in those countries. While metal detectors are used to search for archaeological objects in many, if not most, countries of the world, the sheer diversity of the measures to protect such finds taken by different countries is remarkable (see, for example, Bland 1998).

Among the British contributions, Stuart Campbell, responsible for the administration of Treasure Trove at the National Museums of Scotland, does not attempt to describe the system of Treasure Trove in Scotland but takes a broader approach, discussing the factors that lead metal-detector users in that country to report their finds. Under the Scottish common law doctrine of Treasure Trove there is, in effect, a legal obligation to report all archaeologically significant objects. A very different situation applies in England and Wales, where there is only a legal obligation to report a limited range of objects that fall within the definition of the Treasure Act 1996 (see below), but metal-detector users are encouraged voluntarily to report all archaeological objects under the Portable Antiquities Scheme. There is therefore a marked contrast between the English and Scottish legal régimes and the latter is, on paper, far more straightforward. Campbell argues that a broad definition of Treasure Trove is workable in Scotland where the number of metal-detector users is relatively low, at no more than 500 (in England and Wales, by contrast, the figure is 9,000-10,000), and where most of the terrain does not offer favourable conditions for metal detecting.

Allison Fox discusses the situation on the Isle of Man, a crown dependency that has its own legal regime governing archaeological finds. On Man, a statutory requirement to report all finds (the Manx Museum and National Trust Act 1959) sits rather uncomfortably alongside the old English common law doctrine of Treasure Trove, which only gives the State a legal right to acquire gold and silver objects that have been deliberately hidden and whose owner cannot be traced. A similar situation exists in Northern Ireland, where the Treasure Act 1996 operates alongside other legislative frameworks that affect its statutory requirements and are more extensive than in England and Wales. Fox notes that the authorities on Man are currently in the process of updating this law and will bring the definition of Treasure closer to that of the English Treasure Act 1996.

Of course the largely hostile archaeological response to metal detecting in England and Wales was greatly exacerbated by the phenomenon of 'nighthawking' or illegal metal detecting. As with all types of human activity, illegal behaviour followed close behind the widespread availability of metal detectors in the 1970s. Wilson and Harrison present a useful report on another initiative, led by English Heritage, to combat nighthawking and heritage crime in general. They discuss the Nighthawking Survey, a report commissioned from Oxford Archaeology in 2009 and note that on two key measures (the number of archaeological units that reported raids on their excavations by illegal metal-detector users and the number of Scheduled Monuments that were found to have been attacked), reported incidences had actually gone down when compared with a survey of 1995 (Dobinson and Denison 1995). They also describe the great advances made in the fight against heritage crime (of which illegal detecting is just one part) since the appointment of Chief Inspector Mark Harrison as National Policing and Crime Advisor at English Heritage in 2010. Harrison has followed up a large number of reports of illegal activity with great energy and the results are starting to bear fruit in a number of successful prosecutions, although it would be fair to say that the sentences imposed by the courts still seem to fail to take account of the real archaeological damage caused by this activity. I would note that when Wilson and Harrison discuss the blanket publicity given to the discovery of the Staffordshire Hoard in 2009 and cite anecdotal evidence that this led to an increase in sales of metal detectors, they fall into a trap of assuming that this will have led to an increase in illegal metal detecting. While that may be so, it should not be assumed without independent evidence.

Two detector users, Redmayne and Woodward, describe an Internet forum, the UK Detector Net, which has over 5000 registered users and whose moderators take an active approach to promoting good practice. There is no doubt that Redmayne and Woodward and the other moderators of UK Detector Net such as Peter Twinn have been a great force for the good in educating fellow forum members, but it is a sad thing that not all detecting fora have moderators who strive to promote responsible behaviour. So often online fora can be breeding grounds for half-truths and unfounded rumours.

Ferguson discusses the mixed impact of metal detecting on the relatively new discipline of battlefield (or conflict) archaeology. Systematic metal detecting surveys of battlefields have the potential to give us a great deal of information about the course of battles—the example of a survey of the battlefield of Naseby, led by the archaeologist Glenn Foard, is a case in point—and Ferguson cites a number of examples where individual archaeologically minded detector users have conducted their own surveys. However, there have also been disasters, such as a metal detecing rally held on the battlefield of Marston Moor in 2003. There is no doubt that the organiser of this event used the lure of a well-known battlefield site to attract paying customers, although it is ironic that most metal-detector users in England do not regard musket-balls, the most commonly found artefacts on such sites, as objects of much interest and often do not bother to record them. A clear solution to this problem is to give Registered Battlefield Sites the same legal protection as Scheduled Monuments and only permit metal detecting on them under licence. Until the law is changed in that way, sadly such disasters could recur.

Gransard-Desmond presents an informative picture of the situation regarding metal detecting in France. There were few controls on metal detecting in France until 2004 when the Code du Patrimoine introduced a legal requirement for anyone searching for archaeological objects to obtain authorisation from the state (Northern Irish legislation contains a similar provision). This means that the use of a metal detector to search for archaeological objects is, strictly speaking, illegal, but it is a law that is not enforced. Thus France has the worst of all worlds. Metal detecting is strictly frowned on by the state archaeologists, but it is widespread (Gransard-Desmond quotes an estimate of some 10,000 metal-detector users in France) and many archaeologists and academics outside the state heritage protection bodies study detector finds, although the legality of this is questionable. Meanwhile Gransard-Desmond notes the existence of several metal detecting organisations in France who wish to work with archaeologists, although this is clearly not easy. The net result is that while metal detecting is widespread—and of course the country is likely to be as rich in archaeological finds as England—there are no systematic initiatives to record these finds, with a consequent loss of information.

The last two contributions have a wider focus. Ndukuyakhe Ndlovu discusses the ownership of heritage resources in South Africa. In this case the issues are very different from those that apply in western Europe and Ndlovu is not concerned with metal detecting but the protection of heritage sites. Although the National Heritage Resources Act is a piece of post-apartheid legislation (it dates from 1999), Ndlovu argues that the Act's concern to protect archaeological resources such as rock art can conflict with traditional African ritual practices honouring their dead. As an example he cites the annual ceremony of the Duma clan in honour of their ancestral graves in the uKhahlamba Drakensberg Park where the ceremony is curtailed by the fact that biodiversity regulations mean that the clan members can no longer kill an eland, while concern for rock art images at the site limits their ability to hold their traditional ceremony. Ndlovu argues that the Act needs to be revised to take greater account of African cultural beliefs.

Lastly a US-based contributor, Wayne Sayles, presents a defence of the private collecting of antiquities. Sayles is Executive Director of the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild, a lobby group that defends the rights of collectors and which fights a running battle against attempts by foreign governments seeking bilateral agreements with the US under the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act to restrict the importation of antiquities from their countries.

I am afraid that there is much that is self-serving here. For example, when Sayles condemns the 'intractable claims from the archaeological community that no object from antiquity is of value to society unless its precise archaeological context is known, recorded, and verifiable', one wonders whether he has any appreciation of just how important the information that can be gained from recording a find in its context is. Even more sweeping is his claim 'even if an argument might be made for national retention of certain types, or exceptional examples, of certain artefacts, rarely can a case be made that utilitarian objects like coins are culturally significant objects...'. For someone who writes books about coins, this seems a strange statement indeed.

Equally questionable is Sayles's evident outrage at the fact that 'some archaeologists argue that the looting of ancient sites would not occur were it not for the private collector market': it is self-evident that the reason people loot sites is to recover objects that they can sell. What Sayles should have asked is whether it is ever practical to suppress this market completely, since it has probably existed for almost as long as the artefacts themselves. Even if a state could successfully suppress this market within its own territory, it is highly unlikely that it could ever prevent the outflow of cultural objects to other countries where such a market exists. There may be a valid argument to be made for a private market in antiquities, and the Treasure Act and Portable Antiquities Scheme in England and Wales was established within the context of a régime where such a market exists, but Sayles's bombastic contribution totally fails to make that case.

At this point it may be useful to provide a description of those initiatives.

Until 1996 England and Wales, very unusually, had no legislation governing portable antiquities. The old feudal right to Treasure Trove (under which the king claimed all finds of gold or silver that had been deliberately buried in the ground) had been adapted as an antiquities law in 1886 when the Government started paying finders rewards for finds of Treasure Trove that museums wished to acquire, but this was just an administrative act and no law setting out a sensible definition of Treasure Trove was ever passed; instead the definition was based on case law going back to the 17th century and beyond. So only finds made of gold and silver that had been deliberately buried qualified as Treasure Trove. In practice most Treasure Trove cases were coin hoards, but not all hoards were covered, as small groups that could have been lost did not qualify, nor did hoards of bronze or base metal coins.

Archaeologists pressed for reform throughout the 20th century but, fatally, could never agree on what form that reform should take. The availability of cheap metal detectors in the 1970s suddenly lent a new urgency to the need to reform the law, as the number of objects being found suddenly rocketed, but, with a few exceptions, museums and archaeologists failed to respond adequately. A part of the archaeological establishment responded by trying to introduce controls on metal detecting—the STOP ('Stop Taking our Past') campaign—but this failed to gain political support and simply engendered a climate of distrust between archaeologists and detector users. In 1979 Parliament passed legislation controlling metal detecting on Scheduled Monuments (of which there are some 24,000) but, this apart, it is completely legal to use a metal detector with the permission of the owner of the land in England and Wales. This is in contrast to most European countries, where a licence is needed to search for archaeological objects. In a few parts of England far-seeing archaeologists, notably in the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk, pioneered a system of liaison with detector users (Green and Gregory 1978).

Thanks to the efforts of Lord Perth and others, the UK Parliament finally passed the Treasure Act in 1996 (it came into effect the following year) and this provided a significant, but incremental, change. The Act came into effect in 1997 and applies only to objects found since September 1997. It has effect in England, Wales and Northern Ireland but not Scotland, which has a completely separate legal framework governing finds: in Scotland there is, in effect, a legal requirement to report all finds.

Under the Treasure Act the following finds are Treasure, provided they were found after 24 September 1997:

The Act also contained a provision that allows for regular reviews, following which the definition can be extended. The first review in 2003 led to adding hoards of prehistoric base-metal objects to the categories of Treasure. A second review is now overdue (see below).

Any object that a museum wishes to acquire is valued by a committee of independent experts, the Treasure Valuation Committee, and their remit is to determine the full market value of the object in question; the current chairman is Professor Lord Renfrew of Kaimsthorn, an eminent archaeologist and member of the House of Lords. The reward is normally divided equally between the finder and landowner. The Committee is advised by a panel of valuers drawn from the trade, and interested parties can commission their own valuations which the committee will consider. The reward can be reduced or not paid at all if there is evidence of wrongdoing on the part of the finder or the landowner. Once a valuation has been agreed museums have up to four months to raise money. Archaeologists are not eligible for rewards. Not all finds reported as Treasure are acquired by museums and indeed about 60% of all cases are now disclaimed and returned to the finder who is free to dispose of them as he wishes.

The impact of the Act has been dramatic: before 1997, an average of 26 finds a year were Treasure Trove and offered to museums to acquire; 970 cases were reported in 2011 as Treasure, 95 per cent of these found by amateur metal-detector users (Fig. 1). Since most of the finds that were Treasure Trove before 1997 were coin hoards, it might have been thought that the Act would have only a limited impact on the number of hoards being reported, but in fact the average number of coin hoards since 1997 is 70 a year (half of these are Roman hoards), more than twice the 26 a year logged in the ten years before the change in the law. Since that figure of 26 a year included hoards of bronze coins and small groups of coins that were not Treasure Trove, this increase must reflect a greater willingness by metal-detector users to report their finds.

Figure 1: Finds reported as Treasure Trove (1988-97) and Treasure (since 1997) © British Museum

Of course Treasure finds are only part of the picture: the great majority of archaeological objects found do not qualify as Treasure, but the information they provide can be just as important for our understanding of the past. The Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) was established in parallel with the Treasure Act to encourage amateur finders to report—voluntarily—all the coins and other archaeological objects that they find. This works through a network of locally based 39 Finds Liaison Officers, who between them cover the whole of England and Wales. They have to cope with all types of archaeological finds and so are supported by six specialists, National Finds Advisers. All the finds are recorded onto an online database. which is now the largest resource of its kind in the world, with details of some 825,000 objects reported by over 14,000 individuals. These finds are returned to their finders after recording.

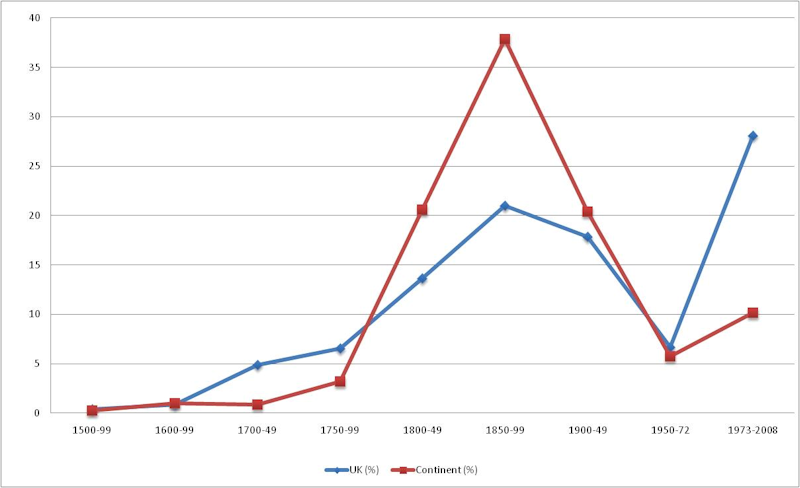

The author recently completed a corpus of all finds of Roman gold coins in Britain in collaboration with Xavier Loriot, who had already done the same for Gaul (Bland and Loriot 2012). This showed that new finds from Britain since the start of metal detecting in the 1970s increased nearly threefold (from 2.4 new finds a year to 6 a year), while the numbers of new finds from France and Germany in the same period remained flat (Fig. 2). The corpus includes finds recorded from sources such as sales catalogues, online sources and metal detecting magazines, and showed that PAS is recording 70 per cent of all current finds.

Figure 2: Single finds of gold coins recorded from the UK (blue line), compared with the Continent (red line), since 1500: percentage of total number of finds © British Museum

It is a priority to record findspots as accurately as possible, so that 90 per cent of all finds are recorded to an area 100m square. When finds are recorded in this way, and the data are integrated with other archaeological finds together with the local archaeological records, the information has huge potential for revealing new sites. A PhD thesis showed that in 10 years the data recorded by PAS had increased the number of Roman sites from two counties (Warwickshire and Worcestershire) by 30 per cent (Brindle 2011). Most archaeology in this country takes place in advance of building development and as sites brought to light by detector finds are mostly rural, most of them are unlikely to have been discovered through the normal archaeological process. 90 per cent of all finds recorded by PAS come from cultivated land where the archaeological contexts have already been disturbed by the plough: when metal detecting is carried out properly on such land, with all finds being carefully recorded, it can be seen as a form of archaeological rescue.

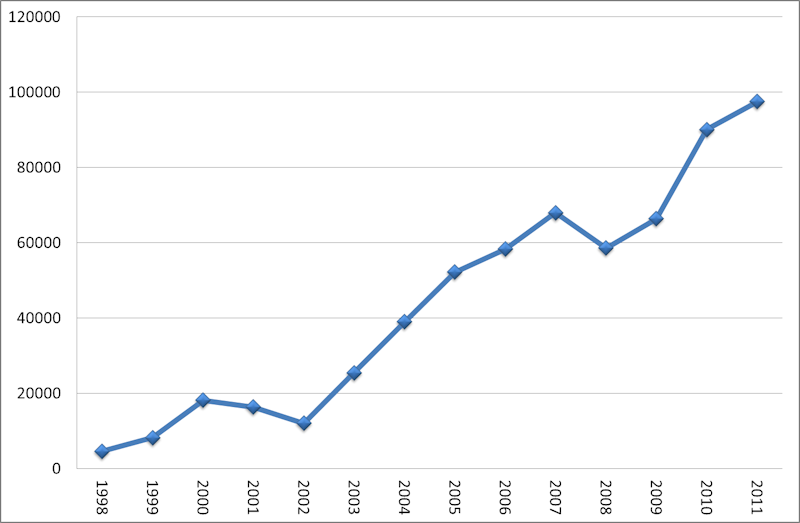

Perhaps the biggest problem for PAS is its own success: we perpetually struggle to record all the reported finds. Although 97,509 finds were added to the database in 2011 (the highest total recorded so far, see Figure 3), we will never have enough staff to record all the finds we would like to, and so in March 2010 a new facility was added to the database to allow amateurs to record their own finds, under supervision, and so far 140 individuals have recorded over 10,000 finds. Persuading the individuals who make finds to take responsibility for ensuring that they are recorded must underlie our future direction, as the flow of new discoveries shows no signs of diminishing.

Figure 3: Numbers of finds recorded on http://finds.org.uk © British Museum

It has sometimes been said as a criticism of PAS that it has not stopped illegal metal detecting in England and Wales, but this is for the simple fact that it was not intended to. This is an enduring problem and we are working closely with English Heritage's Heritage Crime Initiative, which is discussed above. This has had considerable success in targeting illegal detector users, known as 'nighthawks' (see above).

Another way of tackling the problem is to make it harder for the thieves to sell their finds (Bland 2009). At present, it is too easy for the 'nighthawks' to sell their finds to dealers who are happy to purchase such objects without checking that the vendors are acting legally, with the agreement of the landowners. Many items of potential Treasure are openly offered for sale, especially on the eBay website. In October 2006 the PAS signed a memorandum of understanding with eBay whereby eBay will take such items down from its website when notified by PAS and the police. PAS has been monitoring eBay as time allows since then. eBay published comprehensive guidance on buying and selling antiquities on its website for the first time, while PAS also developed its own guidance. PAS has followed up several hundred cases of potential Treasure offered for sale on eBay. Although there have not yet been any criminal prosecutions as a result of this monitoring of eBay, there have been a number of cases where vendors have voluntarily agreed to report the finds they were selling as Treasure. However, monitoring eBay on a daily basis, which is what is needed, is a time-consuming process. More resources are needed in order to pursue this work; these should logically come from eBay which profits from the sale of antiquities on its website.

In 2009 Parliament passed a number of significant amendments to the Treasure Act in the Coroners and Justice Act:

These amendments would help the Act work better and would make it much harder for dealers to sell unreported Treasure finds but regrettably the current Government has not implemented these amendments on grounds of cost. In addition a second review of the Act is overdue: it should have taken place in 2007, but there is now hope that it will happen in 2013. On its agenda will be the possibility of extending the Act and single finds of Roman and Anglo-Saxon gold coins, as well as Roman base-metal hoards have been discussed as possible candidates for adding to the definition of Treasure. It remains to be seen whether the Act will be extended in this way.

Although the Act could be improved and the Portable Antiquities Scheme could benefit from more funding, they have had a major impact. The enormous public interest in the Staffordshire hoard, which was discovered in 2009, gave the PAS a much higher public profile than it had previously enjoyed and in July 2012 ITV screened a series on the work of the Scheme, 'Britain's Secret Treasures', which achieved average viewing figures of 3.6m, a very high figure. A second series is expected in 2013. The more than 825,000 finds recorded by the Scheme are available at http://finds.org.uk for all to see. This is a major tool for research, and over 13 major research-council funded projects, 67 PhDs, and 142 Masters' or Bachelors' dissertations are using the data. Nine of these PhDs have been Collaborative Doctoral Awards studying subjects defined by the staff of the PAS and jointly supervised by them. One of these, by Katherine Robbins (Robbins 2012), was a study of the factors underlying the data recorded on the PAS database and she is now developing that into a national study through a £150,000 grant from the Leverhulme Trust obtained by the author. In November the author obtained a major research grant for £650,000 from the Arts and Humanities Research Council in order to investigate why so many hoards of the Roman period are known from Britain. The Treasure Act and PAS may be a particularly English response to the situation that exists in this country, but they are undoubtedly transforming our understanding of the past of England and Wales.

Bland, R. 1998 'The Treasure Act and the proposal for the voluntary recording of all archaeological finds' in G.T. Denford (ed) Museums in the Landscape: Bridging the Gap, Society of Museum Archaeologists Conference (1996, St Albans, England). The Museum Archaeologist 23, 3-19.

Bland, R. 2009 'The UK as both a source country and a market country: some problems in regulating the market in UK antiquities and the challenge of the Internet' in Simon Mackenzie and Penny Green (eds) Criminology and Archaeology. Studies in Looted Antiquities, Onati International Series in Law and Society. Oxford: Hart Publishing. 83-102.

Bland, R and Loriot, X. 2010 Roman and Early Byzantine Gold Coins found in Britain and Ireland. Royal Numismatic Society.

Brindle, T. 2011 The Portable Antiquities Scheme and Roman Britain. PhD thesis, King's College London (to be published by the British Museum).

Dobinson, C. and Denison, S. 1995 Metal Detecting and Archaeology. York: Council for British Archaeology,

Green, B. and Gregory, T. 1978 'An initiative on the use of metal detectors in Norfolk', Museums Journal 77 (4), 161–62.

Robbins, K. 2012 From Past to Present. Understanding the Impact of Sampling Bias on Data Recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Southampton.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.

File last updated: Tue Mar 5 2013