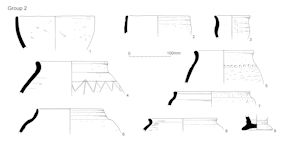

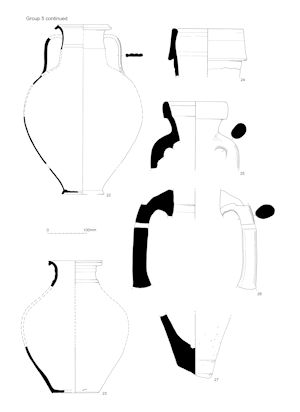

| Number | Fabric Code | Form | Figure 229: Key Pottery Group 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ESH | Jar Cam 254 |  |

| 2 | MICW | Jar EF85 | |

| 3 | MICW | Jar EF83 | |

| 4 | MICW | Jar EF80 | |

| 5 | MICW | Jar EF77 | |

| 6 | GROG | Jar EF76 | |

| 7 | GROG | ?Pedestal jar | |

| 8 | GROG | Jar Cam 259 |

Cite this as: Biddulph, E., Compton, J. and Martin, T.S., 2015 The Late Iron Age and Roman Pottery, in M. Atkinson and S.J. Preston Heybridge: A Late Iron Age and Roman Settlement, Excavations at Elms Farm 1993-5, Internet Archaeology 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.1.biddulph1

The recording, analysis and reporting of the Late Iron Age and Roman pottery was undertaken by a number of people over an extended period of time. Initial recording and assessment was carried out by Colin Wallace. Recommendations for analytical work (see UPD in paper archive at Colchester and Ipswich Museum) were taken up and developed by Scott Martin (see UPD pottery addendum in paper archive). Recording by fabric and vessel form by context, and quantification of the assemblage, was subsequently carried out by the project's three pottery researchers, Edward Biddulph, Joyce Compton and Anne Thompson. Analysis and reporting was largely undertaken by Edward Biddulph and Joyce Compton, with Scott Martin contributing study of the latest Roman material. Additional study has been carried out on particular components of the assemblage by other specialists; their contributions are acknowledged where appropriate.

The Elms Farm excavations yielded more than 282,000 sherds of Late Iron Age and Roman pottery, weighing a total of 6.4 tonnes, from 4986 contexts. Of this, 269,070 sherds, weighing 5213kg, were stratified. This constitutes one of the largest single assemblages of Late Iron Age and Roman pottery to have been studied using modern quantification techniques in Essex and, indeed, in the region. The assemblage is comparable to the 5.7 tonnes of pottery used for detailed analysis at Colchester (Symonds and Wade 1999, 1) and far in excess of the 1.6 tonnes from Chelmsford (Going 1987, 1; 1992a, 93). Spanning the mid-1st century BC to late 4th century+, analysis of this assemblage has provided the opportunity to test critically and enhance current views of chronology and supply principally derived from studies of the pottery from Camulodunum/Colchester and Chelmsford.

The exceptional quality of the assemblage provided an opportunity to investigate a range of aspects for the pottery at Heybridge. Determining a ceramic sequence for the site and the pattern of pottery supply to the settlement were fundamental to the project aims. The analysis, however, was able to go beyond aspects of chronology and supply to explore issues of site development and daily life in the settlement. Pottery was an intermittent part of the local economy, with the presence of kilns confirming that the settlement produced, as well as received, ceramic vessels. Various studies have shown that pottery was used in diverse ways, functional in both ritual and mundane settings (see Vessel function and use). These studies have not been exhaustive and the recorded pottery data provide a comprehensive resource for further research.

The assemblage was recorded on an area-by-area basis (Areas D-R and W) using the divisions devised for excavation purposes. The stratified pottery was sorted into fabric groups and recorded by context to the basic level of sherd count and weight, in grams, following Study Group for Roman Pottery guidelines (1994). The information was recorded on pro forma sheets along with vessel class and form identifications, typological references, dating and other observations. Roman forms were classified using the Chelmsford type series (Going 1987, 13-54; Classes A-S), with the Camulodunum type series (Hawkes and Hull 1947, 215-75; updated by Bidwell and Croom 1999, 468-87) used principally for the Late Iron Age pottery. Roman forms not found in either were classified using regional typologies where possible, such as Monaghan's Upchurch/Thameside series (1987) and Young's Oxfordshire series (1977). Late Iron Age forms not present in the Camulodunum type series have been incorporated into a new site-specific typology published in this volume. Any forms not in the above can be found in the intrinsic pottery section. Unstratified pottery was recorded in less detail, with quantification in fabric groups by weight carried out for all of this material but with sherd counts and form identifications only partially undertaken.

Preliminary dating was undertaken at the time of basic recording and each group assigned to either single or multiple date ranges. The scheme, adopted purely for analytical purposes, comprised sixteen ceramic phases based upon the tripartite division of the centuries covered by the assemblage (i.e. mid-1st century BC to late 4th century+ AD). The detail of this ceramic phasing is held in the archive (x_code_ceramic_phases) and has been converted into a more robust scheme used throughout this report. The ceramic phasing scheme (CP) comprises eleven phases that follow the regional pattern as identified at Chelmsford (Going 1987, Ceramic Phases 1-8). Comparisons can also be made with the ceramic phasing scheme used at Colchester (Symonds and Wade 1999, Period Ending Groups 0-18). Context dating was refined by reference to the stratigraphic record.

| Elms Farm Site Period | Elms Farm CP | Chelmsford CP | Colchester PEG | Date Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | - | Palaeolithic-MIA |

| 2 | 1 | - | - | c. 50-15 BC |

| 2 | 2 | - | 0 | c. 15 BC-AD 20 |

| 2 | 3 | - | 3 | c. AD 20-55 |

| 3 | 4 | 1 | 4-5 | c. AD 55-80 |

| 3 | 5 | 2 | 5-8 | c. AD 80-125 |

| 3 | 6 | 3 | 9-10 | c. AD 125-170 |

| 4 | 7 | 4 | 9-10 | c. AD 170-210 |

| 4 | 8 | 5 | 10-12 | c. AD 210-260 |

| 5 | 9 | 6 | 13-14 | c. AD 260-310 |

| 5 | 10 | 7 | 14-16 | c. AD 310-360 |

| 6 | 11 | 8 | 16-18 | c. AD 360-400+ |

All well-dated, stratigraphically sound and relatively large groups were further quantified by Estimated Vessel Equivalence (EVE) using vessel rim measurements. The values for the percentage of extant rim, expressed as a proportion of a complete rim, and the rim diameter were entered onto a separate set of pro formas along with archive drawing numbers and details such as vessel decoration. A total of 314 fully quantified and described groups (representing 6% by context count or 22% by assemblage weight of the total assemblage) were thus selected. For the purposes of analysis, a further round of criteria subsequently identified a 'pool' of the 152 best groups, which were used to form the basic understanding of pottery supply to the settlement, and as a source of data in the study of the many aspects of pottery use. Forty of the most representative are published in detail, and illustrated, as Key Pottery Groups (KPG). Despite this selection, data drawn from the entire pottery assemblage continued to be used throughout the programme of analysis. That consistently good results were obtained is testament to the effectiveness of even a basic level of recording. To enable manipulation and interrogation of this very large assemblage, all collected data were entered onto FoxPro relational databases (see the archive).

The extensive archive includes the pottery, which has been ordered and boxed into type following the recording protocol. All sets of paper pro forma pottery record sheets are included, along with selected information used during recording and analysis. There are full dating evidence sections for each context/feature that contained pottery. A total of 1973 vessels were drawn as recording progressed.

This section presents a detailed list of the 100 fabrics and fabric groups recorded for the Late Iron Age and Roman pottery assemblage. Of these fabrics, at least thirty-seven were not included in the Chelmsford fabric series. Many would normally be found in contexts dated to the Late Iron Age and are, therefore, unlikely to have occurred at Chelmsford, which was not established until c. AD 60/5 (Going 1987; Drury 1988, 125-8). The Roman pottery volume for Colchester (Symonds and Wade 1999) provides a comprehensive list of the pottery from the colonia, but this too is inadequate in its description of Late Iron Age wares. The Fabrics section is presented in full below since it provides the most extensive list of Late Iron Age and Roman fabrics for the region. It supersedes the numeric system devised for Chelmsford (Going 1987, 3-11) and enhances the system used at Colchester (Symonds and Wade 1999, 2-5, 12). Each fabric is identified by a common name and a mnemonic code and use of this code is standard for all ECC Field Archaeology Unit projects. The scheme provides a high level of standardisation and facilitates easier comparison between sites.

Fabrics are listed in strict alphabetical order by fabric name, followed in brackets by the standard ECC Field Archaeology Unit mnemonic code. The corresponding Chelmsford fabric codes and the National Roman Fabric Reference Collection codes (Tomber and Dore 1998), the latter prefixed NRFRC, have then been appended where applicable. These provide the principal references for fabric descriptions. Fabrics have been described in full in the few instances where no description exists in either volume. A 'thumb-nail' biography for each fabric is provided, comprising a date range specific to Elms Farm, a list of forms present in that fabric, and a brief overview of its occurrence. Most fabrics were present in sufficient quantities to gain an overall date range. In the cases of fabrics where this is equivocal, for instance, where the appearance of a fabric is restricted to a few sherds, a generally accepted published date range, not specific to Elms Farm, is provided instead. Any differences between accepted chronologies and the date range of a fabric at Elms Farm are discussed, as are any notable aspects of form and fabric. The forms encountered in a given fabric are listed below the date. Roman forms were classified using the Chelmsford type series (Going 1987, 13-54), with the Camulodunum type series (Hawkes and Hull 1947) used principally for the Late Iron Age pottery. Roman forms not found in either were classified using regional typologies, where possible. Late Iron Age forms not present in the Camulodunum type series have been incorporated into a new site-specific typology published in this volume. These forms have the prefix EF, followed by the type number. Dragendorff (1895) form codes, which are used universally for samian vessels, have been simplified here. The common abbreviations (Drag. or Dr.) have not been used; Dragendorff forms are denoted solely by the prefix 'f'. Less common form codes, however, such as those delineated by Ludowici (1927) and Curle (1911), are given in full. Finally, a brief overview of the occurrence of a given fabric is provided, with its distribution noted where appropriate. Full distributions by site area for individual fabrics are contained in the archive.

Fabrics were identified and grouped on a macroscopic basis, aided by the use of x20 magnification where necessary. Most fabrics are based on pre-defined fabric divisions and are known by their common names or have direct equivalents published elsewhere. There are, however, some exceptions. Grog-tempered fabrics are not sufficiently represented at Chelmsford for the description offered by Going (1987, 10) to cover the full range of fabric variations. The fabric group has thus been given four subdivisions at Elms Farm in order to record fully these variations. Going's 'Romanizing wares', fabric codes 34 and 45, are now identified under the umbrella code for black-surfaced wares (BSW). During the recording stage for the purpose of analysis, mortaria were assigned specific fabric codes comprising the relevant fabric code and the suffix 'M'. Because mortaria are just one form within a product range, their fabric descriptions have been incorporated with the generic fabric group, where appropriate. This allows comment to be made on the full range of forms and the scale of production of individual industries. The descriptions for the amphora fabrics have been compiled with the assistance of Dr Paul Sealey, whose contribution is gratefully acknowledged. Condensed entries for these are given here, following the alphabetic system in Tomber and Dore (1998, 82-113); fuller descriptions for all of the amphora fabrics at Elms Farm are held in the archive. A limited programme of thin-sectioning was undertaken by Dr D.F. Williams of Southampton University. Summary results of this programme have been incorporated with the relevant fabric descriptions, where appropriate and the results for pottery from the kilns can be found in the relevant section. The full report by Dr Williams forms part of the research archive. The archive also contains a full list of the thin-sectioning results for selected vessels from pyre-debris pit 15417 (KPG5).

This section incorporates thirty-nine pottery groups spanning eleven ceramic phases, with one further group representing the immediate post-Roman period. These groups, encompassing seventy-eight contexts, were selected from an initial list of some 300 fully quantified contexts and are among the best in ceramic terms at Elms Farm. They have secure and narrow date-ranges, display low residuality (albeit increasing in the Late Roman phases), and are largely free of contamination. The groups are generally large, usually exceed a total weight of 2kg, and the pottery is in good condition. A further requirement for their inclusion here is that the pottery is illustrated, although Key Pottery Group 29 is the exception. A number of roles are served. An unrivalled collection of fully quantified groups is presented, and these form the basis for detailed comparison with the pottery from other sites. The uniform treatment accorded to both Late Iron Age and Roman groups has facilitated a consistent approach to subsequent analysis. Ordered chronologically, the groups provide 'snapshots' of shifting supply patterns and vessel use through time. Both typical and atypical groups within each ceramic phase are presented here. Typical groups are perhaps best described as conforming most closely to the 'average' for supply or assemblage composition in a given ceramic phase, as described in the next section. Conversely, atypical groups diverge from the average and are illustrated to highlight the diversity of pottery deposits.

Each of the Key Pottery Groups (KPG) has been assigned to a ceramic phase. Within each phase, the groups are ordered to reflect chronological progression. All of the groups follow a consistent format. A table accompanies each, in which the quantified data (sherd count, sherd weight, and EVE) is presented. This is followed by a summary of assemblage composition, dating evidence, and justification for selection. Comments on condition and fragmentation are based on recorded observations and average sherd weights. Most assemblages comprise the pottery from a single context; the remainder are composites of multiple fills within a feature. A summary is provided in Table 2 below. The prefix EF, used to designate Late Iron Age forms which are not attested at Camulodunum, refers to vessels catalogued in the Elms Farm typology. Full quantification of the Key Pottery Groups entailed measuring the extant section of the rim for all the vessels present. This measurement is normally known as Estimated Vessel Equivalence (EVE). The study at Elms Farm has used rim measurements only; bases are not included in the statistics.

The groups presented in this section provide some of the principal, but by no means all, data on which subsequent analysis was based. They have been of most use in drawing out trends in pottery supply and use, which form the basis of the Pottery Supply section. To ensure reliability when conducting this analysis, a pool of other fully quantified, well-dated groups was additionally used, expanding the dataset to 106 groups (183 contexts). These have been excluded from the pottery sequence because the selected KPGs adequately reflect pottery supply and use, or, more simply, because they are not illustrated. Full data for the wider pool can be found in the archive.

A feature of the Key Pottery Group is low residuality. The issue of residuality, itself a major component of the pottery analysis along with other aspects of context formation processes, cannot be dealt with satisfactorily by these groups alone. Studies of residuality, deposition and intra-site comparisons form part of the research archive.

| Ceramic phase | Chelm. CP | Colch. PEG | Key group | Feature | Contexts | Area | Date range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | 1 | ditch 25094 | 19116, 19145 | P | c. 50-30 bc |

| 2 | ditch 25252 | 6875, 6907, 6957 | H | c. 50-25 bc | |||

| 3 | pit 8786 | 8785 | P | c. 30 bc | |||

| 4 | pit 11342 | 11329 | N | c. 25-10 bc | |||

| 2 | - | 0 | 5 | pit 15417 | 15416, 15418, 15420, 15490 | M | c. 10 bc-ad 5 |

| 6 | pit 11344 | 11343 | N | c. 5 bc-ad 10 | |||

| 7 | pit 9611 | 9585 , 9610 | D | c. AD 1-10 | |||

| 8 | pit 11316 | 11269, 11301 | N | c. AD 5-20 | |||

| 9 | pit 8282 | 8271 | E | c. AD 5-20 | |||

| 10 | pit 19104 | 19105, 19107, 19109, 19110, 19111 | P | c. AD 1-25 | |||

| 3 | - | 3 | 11 | pit 8026 | 8003 , 8014, 8018 | E | c. AD 20-40 |

| 12 | pit 9230 | 9231 | D | c. AD 20-45 | |||

| 13 | pit 7167 | 7168, 7178, 7179 | G | c. AD 25-45 | |||

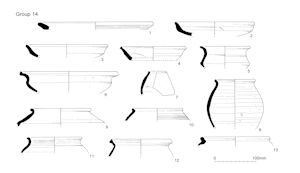

| 14 | pit 11723 | 11720 | N | c. AD 45-55 | |||

| 4 | 1 | 4-5 | 15 | ditch 25018 | 9214 | D | c. AD 50/55-60 |

| 16 | pit 9218 | 9217, 9370 | D | c. AD 55-65 | |||

| 17 | pit 20008 | 20009 | L | c. AD 70 | |||

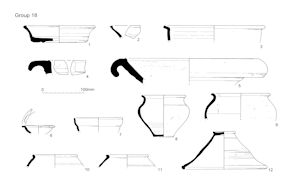

| 18 | pit 24013 | 24014 | M | c. AD 70-80 | |||

| 5 | 2 | 5-8 | 19 | pit 15773 | 24258 | M | c. AD 80-100 |

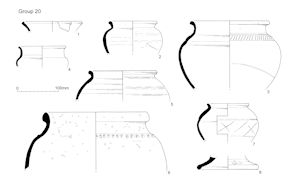

| 20 | pit 6201 | 6203 | H | c. AD 100-120 | |||

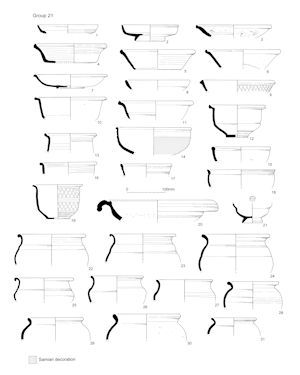

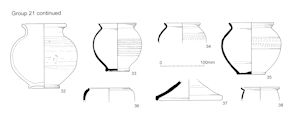

| 21 | pit 5147 | 5146 | J | c. AD 120/25 | |||

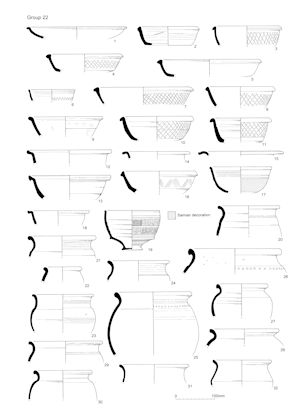

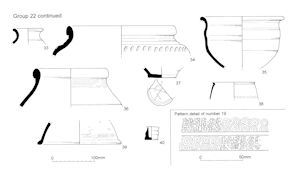

| 6 | 3 | 9-10 | 22 | ditch 25245 | 10182 | F | c. AD 120/5-150 |

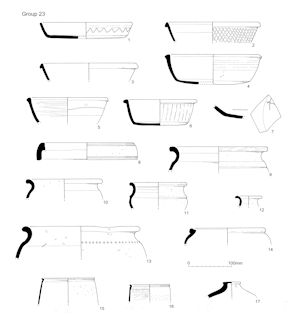

| 23 | pit 7118 | 7119, 7116 | G | c. AD 155/60 | |||

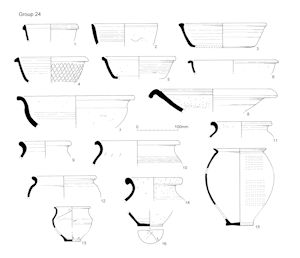

| 24 | pit 9029 | 9028, 9064 | D | c. AD 140-160 | |||

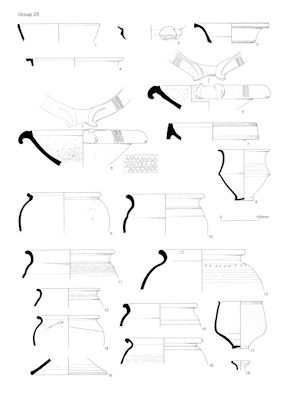

| 7 | 4 | 9-10 | 25 | pit 7122 | 7123 | G | c. AD 170-200 |

| 26 | well 6280 | 16083 | H | c. AD 190-200 | |||

| 27 | stoke-hole 1589 | all deposits (20) | W | c. AD 190-210 | |||

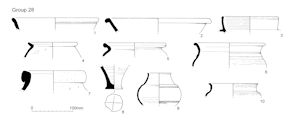

| 8 | 5 | 10-12 | 28 | pit 6182 | 6178 | H | c. AD 200/10-230 |

| 29 | pit 16088 | 16073 | H | c. AD 210-250 | |||

| 30 | pit 10062 | 10061 | E | c. AD 250/60 | |||

| 9 | 6 | 13-14 | 31 | pit 11303 | 11302 | N | c. AD 250/70 |

| 32 | pit 6267 | 6268 | H | c. AD 260-300 | |||

| 33 | ditch 25270 | 12026, 12029 | R | c. AD 290-310 | |||

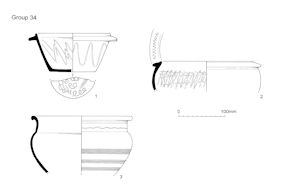

| 10 | 7 | 14-16 | 34 | pit 14125 | 4315 | K | c. AD 310-330 |

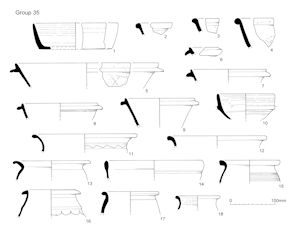

| 35 | pit 8745 | 8766 | P | c. AD 310-350 | |||

| 36 | pit 10067 | 10017 | E | c. AD 350-400 | |||

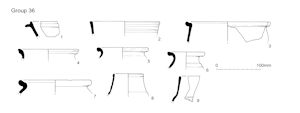

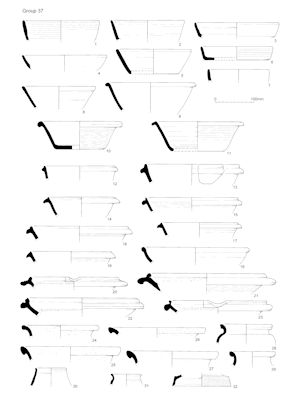

| 11 | 8 | 17-18 | 37 | pit 5209 | 5210 | J | c. AD 350-400 |

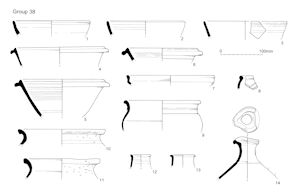

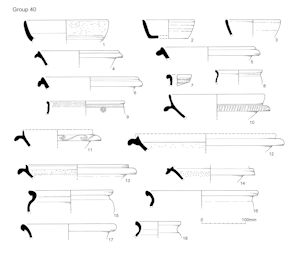

| 38 | gully 25079 | 15056 | M | c. AD 360/70-400 | |||

| 39 | well 5806 | 5763 | I | c. AD 370-400+ | |||

| post Roman | - | - | 40 | pit 14529 | 14528, 14558, 14613 | L | c. AD 400+ |

Thirteen groups, with a total weight of 51.5kg, and 21.51 EVE, have been assigned to this ceramic phase, of which four (21kg, 11.39 EVE) are presented below. Most assemblages comprise mainly coarse wares, with the occasional presence of Dressel 1 amphora and Central Gaulish imports. The majority of the groups assigned to the phase came from the southern zone of the settlement. Independent dating evidence occurs in the form of two coins, a Class I/II potin (SF5645) in ditch segment 16018, and a potin fragment (SF6841) in ditch segment 8208. Quantified groups of this date are few but comparisons may be drawn with the pottery types from the Airport Catering Site, Stansted (Going 2004) and Ditch 350 at Kelvedon (Rodwell 1988). Residuality in all groups is negligible, though earlier prehistoric pottery occurs in ditch segment 19144 in the form of three flint-tempered body sherds weighing 30g.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | EVE % | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESH | 1 | 8 | 8 | <1% | 0.05 | 6% | Jar Cam 254 |

| GROG | 57 | 486 | 9 | 24% | 0.27 | 32% | Jars EF76 Cam 219 Cam 259 |

| GROGC | 31 | 784 | 25 | 39% | 0.03 | 4% | Jar Cam 255 |

| MICW | 37 | 744 | 21 | 37% | 0.49 | 58% | Jars EF77 EF80 EF83 EF85 |

| Total | 126 | 2020 | 0.84 |

This group is representative of the assemblages recovered from contexts dating to the transitional period between the middle and Late Iron Ages, although relatively few of these features were identified. A feasible date for this assemblage is c. 50-30 BC. This is the smallest Ceramic Phase 1 group and is composed entirely of jars, mainly handmade, of which sand-tempered coarse wares form a major component. Imports, including amphoras, are absent. The finer grog-tempered jars are fragmentary.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AITAB | 1 | 314 | 314 | 7% | Dressel 1 | ||

| GROGRS | 4 | 16 | 4 | <1% | |||

| GROG | 124 | 1536 | 12 | 36% | 1.14 | 70% | Bowl EF41, jars EF79 EF104 EF106 Cam 229 G3 |

| GROGC | 111 | 2049 | 18 | 48% | 0.35 | 21% | Jar EF107 |

| MICW | 24 | 346 | 14 | 8% | 0.14 | 9% | Bowl EF31, jar EF98 |

| Total | 264 | 4261 | 1.63 |

Handmade jars again dominate this assemblage, although here the sand-tempered coarse wares form a much smaller proportion, giving way to grog-tempered fabrics. This is a trait that is common for the remainder of the ceramic phase. Dressel 1 amphora is present, but there are no other imports. The coin evidence suggests a date early in the ceramic phase, between perhaps 50 BC and 25 BC. Four small sherds (34g) of Roman grey ware present in the upper fills are clearly intrusive and have been excluded from the table.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUF | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | |||

| GROG | 292 | 4120 | 14 | 51% | 3.40 | 61% | Bowl Cam 231, jars EF81 EF82 EF86 EF89 EF110 EF138 EF139 |

| GROGC | 64 | 2170 | 34 | 27% | 0.13 | 2% | Jar Cam 270 |

| MICW | 78 | 1697 | 22 | 21% | 1.88 | 34% | Jars, handmade (MIA style) |

| NGWFS | 3 | 34 | 11 | <1% | 0.08 | 1% | Beaker Cam 113 |

| TNM | 1 | 30 | 30 | <1% | 0.12 | 2% | Platter Cam 1 |

| Total | 439 | 8057 | 5.61 |

This assemblage demonstrates a greater diversity of form and fabric. There are platters, bowls and beakers present alongside the jars. The latter are still mainly handmade, but now grog-tempered pottery forms the larger component. A small number of imports are present, accounting for just over 3% by EVE. The Central Gaulish Cam 1 platter is among the earliest imports to Britain, and the North Gaulish Cam 113 beaker is typologically early in form. The tiny sherd of buff ware may well be an import, possibly from an amphora. A date of c. 30 BC is proposed for the group. Substantial parts of several vessels are present, allowing for their reconstruction.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AITAD | 2 | 84 | 42 | 1% | Dressel 1 | ||

| AMISC | 2 | 64 | 32 | 1% | |||

| CGFCS | 19 | 126 | 7 | 2% | 0.08 | 2% | Flagon Cam 165 |

| GROG | 180 | 3228 | 18 | 48% | 1.46 | 44% | Bowl Cam 211, jars Cam 220 Cam 249 Cam 256 Cam 264 G19 |

| GROGC | 100 | 2708 | 27 | 40% | 1.08 | 33% | Jars EF119 Cam 255 Cam 266 |

| GROGRS | 21 | 505 | 24 | 7% | 0.69 | 21% | Jar Cam 256, flagon handle |

| THORN | 1 | 8 | 8 | <1% | Beaker base | ||

| TRCG | 1 | 22 | 22 | <1% | Platter base | ||

| Total | 326 | 6745 | 3.31 |

Pottery Group 4 is typical of the later part of the Ceramic Phase 1 date range, perhaps 25-10 BC. It comprises a variety of grog-tempered forms, including the handle from a flagon, although jars still predominate. Sand-tempered coarse ware is no longer present in this particular group, and forms a very small proportion for the remainder of the phase in others. Imports are few, mainly Dressel 1 amphoras, while Central Gaulish vessels are more prevalent. The latter were imported into southern Britain from c. 25 BC (Rigby 1986b, 270). Increased diversity of form is apparent, typical of assemblages towards the final decades of the 1st century BC and later. The average sherd weight is generally high, but the flagon is fragmentary, demonstrating the fragile, thin-walled nature of these Central Gaulish vessels.

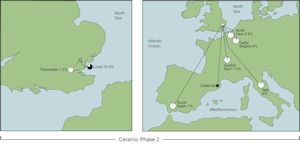

Fourteen groups, with a total weight of 155.8kg and 52.68 EVE, have been assigned to this ceramic phase. Six of these (101.5kg, 34.81 EVE) are presented below to illustrate the pottery which is characteristic of the phase, although the pottery from pit 15417 is, in many ways, atypical. Ceramic Phase 2 groups came mainly from the northern and southern settlement zones. Few assemblages of similar date have been quantified, but groups B50, C5 and C27 from Puckeridge-Braughing in Hertfordshire (Witherington and Trow 1988) provide comparable data. Assigned to this phase, though not presented here, is a cremation burial assemblage (8177) accompanied by fragments of an iron brooch-and-ring ensemble (SF7019) (see The brooches), which has been dated broadly late 1st century BC to early 1st century AD. In addition, two Colchester brooches (SF2393, SF378), dated c. AD 10-70 (see The brooches) occur in features assigned to this phase, one from pit 7415 and the other from pit 4026. Supporting dating evidence is provided by the presence of Arretine ware. Platter floor sherds from pit 9611 are dated to 15 BC-AD 20 and platter rim sherds from pits 7060 and 10288 are both dated to c. 15 BC-AD 10. Residuality is apparent in the later part of the phase, in particular the Dressel 1 amphora and sand-tempered pottery, and occasional earlier prehistoric sherds. The fragmentary nature of some of the grog-tempered pottery may also indicate residuality, although in this fabric this is harder to assess.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AITAB | 139 | 10002 | 72 | 17% | Dressel 1 | ||

| AITAC | 152 | 11391M | 75 | 19% | 0.79 | 8% | Dressel 1 |

| AITAD | 528 | 20897 | 35 | 36% | 0.68 | 6% | Dressel 1 |

| CGFCS | 37 | 436 | 12 | 1% | 0.18 | 2% | Flagon Cam 165 |

| ESH | 50 | 930 | 19 | 2% | 0.76 | 7% | Jar Cam 255 |

| GROG | 356 | 11095 | 31 | 19% | 5.09 | 48% | Bowl Cam 253, jars Cam 204 Cam 218 Cam 220 Cam 221 Cam 259, beakers Cam 115 Cam 118, flagon EF196 |

| GROGC | 7 | 344 | 49 | 1% | |||

| IBUFM | 10 | 464 | 46 | 1% | 0.01 | <1% | Mortarium Cam 191-type (EF74) |

| PR | 25 | 630 | 25 | 1% | 0.48 | 5% | Platter EF23 |

| TNM | 2 | 128 | 64 | <1% | 0.28 | 3% | Platter Cam 1 |

| TR | 173 | 2026 | 12 | 4% | 1.93 | 18% | Platters Cam 2 Cam 5, beaker Cam 112 |

| MICW | 1 | 26 | 26 | <1% | |||

| NGWF | 4 | 100 | 25 | <1% | 0.30 | 3% | Beaker Cam 113 |

| Total | 1484 | 58469 | 10.50 |

This pottery, although almost certainly pyre debris, demonstrates the diversity of fabric and form associated with assemblages deposited at the beginning of Phase 2. This large collection of pottery can probably be dated to the very end of the 1st century BC or beginning of the 1st century AD. Grog-tempered pottery predominates at 48% by EVE, and there are substantial parts of three Dressel 1 amphoras present plus two other vessel types imported from Italy. These, a Pompeian-red ware platter and a wall-sided gritless mortarium, are both typologically early forms. There are also imports from Central Gaul, and Gallo-Belgic ware is now in evidence in the form of terra rubra. The sherd of sand-tempered coarse ware is residual in this feature. Although large and conjoining sherds from many of the vessels are present, the pottery has been burnt to varying degrees, resulting in distortion, discolouration and much splitting along heat-fractures.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARCAT | 1 | 449 | 449 | 5% | Pascual 1 | ||

| AWINE | 1 | 82 | 82 | 1% | |||

| CGFCS | 9 | 42 | 5 | <1% | Flagon handle | ||

| CGMIC | 36 | 242 | 7 | 3% | 0.47 | 11% | Beaker Cam 102 |

| GROG | 197 | 2710 | 14 | 29% | 2.26 | 51% | Platter Cam 21, dish EF26, jars G19 Cam 219 Cam 249, beaker Cam 115 |

| GROGC | 214 | 5501 | 26 | 58% | 1.29 | 29% | Jars EF116 Cam 255 Cam 271 G44 |

| IMIC | 1 | 14 | 14 | <1% | Balsamarium foot (Cam 196) | ||

| TN | 3 | 52 | 17 | 1% | |||

| TNM | 4 | 50 | 13 | 1% | 0.03 | 1% | Bowl Cam 51 |

| TR | 49 | 320 | 7 | 3% | 0.36 | 8% | Platter Cam 5, beaker Cam 112 |

| Total | 515 | 9462 | 4.41 |

This assemblage again exhibits characteristics that continue from Ceramic Phase 1, demonstrating the continuance of pottery types, such as Central Gaulish ware, into the first decades of the 1st century AD. Wine amphoras Pascual 1 and Dressel 2-4 have made an appearance and the wider range of Gallo-Belgic wares now includes terra nigra. Imports account for 13% of the assemblage by weight, but grog-tempered pottery predominates, as expected. The forms present include bowls and beakers along with the platters and jars. Many of these vessels are copies of imported forms. The finer vessels are fragmentary. The assemblage dates to the end of the 1st century BC into the first decade of the 1st century AD.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weighth | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AITAL | 3 | 391 | 130 | 2% | Dressel 1 | ||

| AWINC | 4 | 120 | 30 | 1% | Dressel 2-4 | ||

| BSW | 4 | 132 | 33 | 1% | |||

| BUF | 1 | 8 | 8 | <1% | |||

| CGFCS | 36 | 895 | 25 | 6% | 0.54 | 7% | Flagon Cam 165 |

| CGMIC | 5 | 44 | 9 | <1% | 0.25 | 3% | Beaker Cam 102 |

| GROG | 256 | 3690 | 14 | 23% | 3.16 | 40% | Platters Cam 21 Cam 22, bowls Cam 230 Cam 214, jars EF103 EF153 EF154 Cam 249 Cam 229 G19 G20, lid |

| GROGC | 318 | 9763 | 31 | 61% | 2.23 | 28% | Jars Cam 218 Cam 219 Cam 255 Cam 259 G4, funnel N2 |

| GROGRF | 14 | 74 | 5 | <1% | |||

| GROGRS | 2 | 26 | 13 | <1% | 0.23 | 3% | Jar G19 |

| GRS | 2 | 10 | 5 | <1% | |||

| ITSW | 3 | 8 | 3 | <1% | Platter | ||

| NGWF | 4 | 16 | 4 | <1% | |||

| NGWFS | 5 | 31 | 6 | <1% | |||

| RED | 4 | 24 | 6 | <1% | |||

| STOR | 1 | 32 | 32 | <1% | |||

| TN | 3 | 44 | 15 | <1% | |||

| TNM | 5 | 374 | 75 | 2% | 0.57 | 7% | Platter Cam 1 |

| TR | 22 | 238 | 11 | 1% | 0.85 | 11% | Platters Cam 2 Cam 4, cup Cam 56, beakers Cam 82 Cam 112 |

| PREHIST | 1 | 20 | 20 | <1% | 0.02 | <1% | Small bucket urn |

| Total | 693 | 15940 | 7.85 |

This large assemblage falls in the middle of Ceramic Phase 2, perhaps spanning the first decade of the 1st century AD. Grog-tempered pottery again predominates at 85% by weight, and the range of imports has expanded to include North Gaulish fine white ware and Arretine. Central Gaulish vessels are still in evidence, and there is Dressel 2-4 amphora present along with the Dressel 1, although the latter must be residual by this time. This group contains a wide range of fabrics with a wider range of forms, including a specialised form, a funnel, in grog-tempered ware. Many grog-tempered forms are, again, copies of imports. The few Roman sherds present (fabrics BSW, GRS and STOR) are from the top fill and probably intrusive.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AITAD | 3 | 114 | 38 | 1% | Dressel 1 | ||

| ARCAT | 2 | 227 | 114 | 3% | Pascual 1 | ||

| AWINC | 2 | 109 | 55 | 1% | Dressel 2-4 | ||

| CGFCS | 2 | 22 | 11 | <1% | 0.19 | 4% | Flagon Cam 165 |

| CGMIC | 31 | 274 | 9 | 4% | 0.57 | 12% | Beaker Cam 102 |

| GROG | 230 | 2847 | 12 | 37% | 1.75 | 38% | Bowl Cam 210, jars EF117 Cam 204 Cam 260, beakers EF189 Cam 85 Cam 115, flagon handle |

| GROGC | 160 | 3414 | 21 | 45% | 1.62 | 35% | Jars Cam 254 Cam 255 Cam 256 Cam 257 Cam 259 |

| GROGRS | 10 | 158 | 16 | 2% | 0.06 | 1% | Bowl Cam 43 |

| NGWF | 4 | 14 | 4 | <1% | |||

| PR | 1 | 30 | 30 | <1% | 0.06 | 1% | Platter Cam 17 |

| TN | 1 | 36 | 36 | <1% | 0.09 | 2% | Platter Cam 2 |

| TNM | 11 | 266 | 24 | 3% | 0.10 | 2% | Platters Cam 1 Cam 4, bowl Cam 51 |

| TR | 13 | 108 | 8 | 1% | 0.18 | 4% | Beaker Cam 82 |

| Total | 470 | 7619 | 4.62 |

This group illustrates the diversity of fabric and form typical of the mid- to later part of the ceramic phase (c. AD 5-20). Grog-tempered pottery continues to form the major component at 84% by weight. Platters appear in Gallo-Belgic fabrics only; grog-tempered copies are confined to beaker and bowl forms. The Cam 17 platter in Pompeian-red ware is a type more commonly imported from Italy from c. AD 40. The finer vessels are fragmentary, and the Dressel 1 amphora is residual.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AITAL | 1 | 27 | 27 | <1% | 0.13 | 2% | Dressel 2-4 |

| AMISC | 1 | 18 | 18 | <1% | |||

| ASALA | 4 | 616 | 154 | 8% | Beltrán 1 | ||

| CGFCS | 1 | 32 | 32 | <1% | Flagon handle | ||

| CGMIC | 4 | 14 | 4 | <1% | |||

| GROG | 128 | 1914 | 15 | 24% | 4.12 | 63% | Platters EF6 Cam 21 Cam 31, jars Cam 218 Cam 221 Cam 232 Cam 264, strainer bowl M1 |

| GROGC | 77 | 5059 | 66> | 63% | 2.21 | 34% | Bowl EF28, jars EF133 Cam 255 Cam 259 Cam 270 |

| GROGRF | 4 | 10 | 3 | <1% | 0.01 | <1% | Beaker Cam 116 |

| NGWF | 12 | 136 | 11 | 2% | |||

| STOR | 2 | 138 | 69 | 2% | Jar Cam 270 | ||

| TR | 2 | 34 | 17 | <1% | 0.06 | 1% | Platter Cam 5 |

| Total | 236 | 7998 | 6.53 |

Although consisting mainly of grog-tempered ware (87% by weight), KPG9 is, again, characteristic of the mid- to later end of the date range. Several grog-tempered forms are types which continue into the mid-1st century AD. Salazon amphoras have made an appearance, although the range of imports is now less extensive. There is nothing obviously residual in the group.

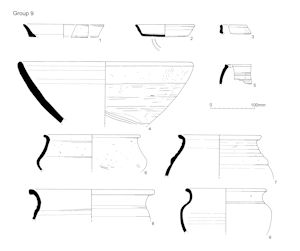

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABSAN | 1 | 12 | 12 | 1% | Dressel 2-4 | ||

| BUF | 3 | 30 | 10 | 1% | |||

| CGFCS | 5 | 87 | 17 | 4% | |||

| GROG | 79 | 1322 | 17 | 63% | 0.61 | 68% | Bowls EF46 Cam 211, jars EF135 Cam 218 Cam 249 Cam 256 |

| GROGC | 18 | 462 | 26 | 22% | 0.03 | 3% | Jar Cam 255 |

| MICW | 6 | 114 | 19 | 5% | 0.09 | 10% | Jar EF78 |

| NGWFS | 12 | 42 | 4 | 2% | Beaker EF195 | ||

| TNM | 1 | 8 | 8 | <1% | 0.02 | 2% | Platter Cam 1 |

| TR | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | 0.15 | 17% | Beaker Cam 112 |

| Total | 126 | 2083 | 0.90 |

Although relatively small, with a narrower range of fabrics, this assemblage is typical of Ceramic Phase 2, and is dated broadly to the first quarter of the 1st century AD. It is included here because the feature cuts ditch segment 19115 (Ceramic Phase 1). The assemblage, therefore, forms part of a ceramic sequence with the pottery from KPG1. The sand-tempered coarse ware (Figure 240, no. 8) is residual from this earlier feature.

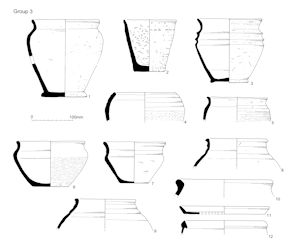

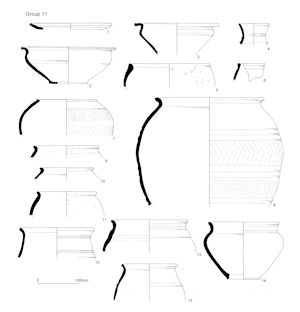

Eleven groups, with a total weight of 60.3kg and 31.22 EVE, have been assigned to this ceramic phase, four of which (30.5kg, 14.76 EVE) are presented below. Phase 3 groups came mainly from the northern and southern zones. The phase is characterised by the gradual appearance of samian and various Roman fabrics, accompanied by a decline in other imported fine wares and amphoras. Two groups of pottery, Group 1 from ditch 1124 and Group 2 from slots 662/4, at Ivy Chimneys, Witham (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999) provide broad comparisons. Independent dating evidence occurs in the form of a Langton Down brooch (SF7820) from pit 24181 and a coin of Cunobelin (SF2385) from pit 7167, both current in the first half of the 1st century AD. Additional dating is provided by the presence of Neronian samian in contexts assigned to the later part of the phase and the appearance of Verulamium region white ware and Central Gaulish glazed ware, both mid-1st century AD types. Grog-tempered pottery continues to form a major component, averaging 85%, of all assemblages assigned to this phase. Residuality is apparent in the presence of prehistoric pottery, handmade vessels and many of the Central Gaulish products.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 1 | 77 | 77 | 1% | Dressel 20 | ||

| AITAL | 1 | 11 | 11 | <1% | Dressel 2-4 | ||

| ASALA | 3 | 482 | 161 | 5% | |||

| CGFCS | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | |||

| CGMIC | 1 | 8 | 8 | <1% | |||

| ESH | 6 | 224 | 37 | 2% | 0.62 | 10% | Jar Cam 254 |

| GROG | 160 | 5712 | 36 | 58% | 3.31 | 55% | Platters EF16 Cam 32, bowls EF72 Cam 241/6, cup Cam 212, jars EF146 EF179 Cam 218 Cam 219 Cam 249 Cam 221, beakers Cam 116 Cam 118 Cam 119 |

| GROGC | 48 | 2931 | 61 | 30% | 1.41 | 24% | Jars Cam 259 Cam 258 Cam 271 G5 G44 |

| GROGRF | 3 | 132 | 44 | 1% | 0.12 | 2% | Bowl |

| GRS | 1 | 10 | 10 | <1% | 0.10 | 2% | Beaker H7 |

| NGWF | 2 | 76 | 38 | 1% | 0.08 | 1% | Beaker Cam 113 |

| SGSW | 2 | 2 | 1 | <1% | |||

| TN | 5 | 180 | 36 | 2% | 0.15 | 3% | Platter Cam 2 |

| TR | 4 | 24 | 6 | <1% | 0.18 | 3% | Beaker Cam 112 |

| Total | 238 | 9873 | 5.97 |

Pottery Group 11 is typical of the earliest part of Ceramic Phase 3, c. AD 20-40, and is dominated by grog-tempered pottery in a wide variety of forms. Imports are present in the form of Gallo-Belgic and Central Gaulish ware, although the latter is represented by small body sherds only. Salazon amphora sherds are present and Dressel 20 amphora has made an appearance, whereas Dressel 2-4 wine amphora is reduced to a single small body sherd. There are a few sherds in Roman fabrics, including a tiny sherd of south Gaulish samian, and Romanised forms in grog-tempered wares are increasingly evident. The average sherd weight is generally high, although the finer fabrics tend to be fragmentary.

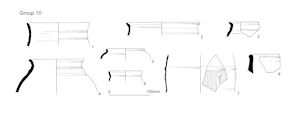

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AITAL | 2 | 36 | 18 | 1% | Dressel 2-4 | ||

| BSW | 4 | 48 | 12 | 1% | |||

| GROG | 265 | 3306 | 12 | 66% | 1.73 | 73% | Bowls Cam 212 Cam 244, jars Cam 219 Cam 229 Cam 249, beaker Cam 115, lid K6 |

| GROGC | 44 | 1396 | 32 | 28% | |||

| GROGRS | 8 | 142 | 18 | 2% | 0.29 | 12% | Bowl EF73, flagon |

| GRS | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | |||

| RED | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | |||

| TR | 25 | 76 | 3 | 2% | 0.35 | 15% | Beaker Cam 112 |

| PREHIST | 3 | 18 | 6 | <1% | |||

| Total | 353 | 5032 | 2.37 |

Grog-tempered pottery in a variety of forms again predominates at 96% by weight. The group is dated broadly to c. AD 20-45. There is a narrow range of fabrics present; unusually, terra rubra is the sole imported fine ware type represented. Amphoras are again scarce and Roman fabrics are still very much in the minority. The pottery is fragmentary, but there is very little that is obviously residual, apart from three small flint-tempered body sherds of prehistoric date.

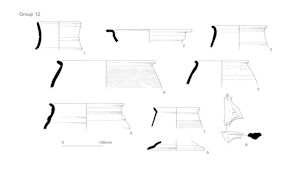

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 4 | 108 | 27 | 1% | Dressel 20 | ||

| AITAL | 1 | 199 | 199 | 2% | Dressel 1 | ||

| AMISC | 1 | 22 | 22 | <1% | |||

| ASALA | 1 | 66 | 66 | 1% | |||

| BSW | 33 | 280 | 8 | 3% | |||

| BUF | 8 | 16 | 2 | <1% | |||

| CGFCS | 15 | 116 | 8 | 1% | |||

| GROG | 427 | 5850 | 14 | 59% | 2.78 | 82% | Platters Cam 21 Cam 33, bowls EF38 EF42 Cam 210 Cam 252, jars EF129 Cam 218 Cam 229 Cam 254 Cam 259 G17 G19, beakers EF188 H7 |

| GROGC | 39 | 1780 | 46 | 18% | 0.12 | 4% | Jar Cam 270 |

| GRS | 28 | 160 | 6 | 2% | |||

| MICW | 10 | 160 | 16 | 2% | 0.12 | 4% | Jar |

| NGWF | 4 | 24 | 6 | <1% | |||

| NGWFS | 2 | 6 | 3 | <1% | |||

| STOR | 26 | 1095 | 42 | 11% | |||

| TN | 1 | 22 | 22 | <1% | |||

| TNM | 5 | 34 | 7 | <1% | 0.06 | 2% | Platter EF20, beaker EF192 |

| TR | 8 | 48 | 6 | <1% | 0.30 | 9% | Platter Cam 8, cup Cam 56, beaker Cam 112 |

| Total | 613 | 9986 | 3.38 |

Dressel 20 and salazon amphoras are present in this assemblage, but the sherd of Dressel 1 wine amphora is residual. Although grog-tempered pottery continues to predominate, Roman fabrics are beginning to form an increased part of the assemblage. Imports are again represented mainly by body sherds, while the forms present in Gallo-Belgic ware are the latest types to be produced. The newly identified forms in micaceous terra nigra may reflect the continuance of this industry beyond the first two decades AD. The group is dated to c. AD 25-45. Besides the Dressel 1, only the handmade jars are likely to be residual.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 6 | 229 | 38 | 4% | Dressel 20 | ||

| AWINE | 1 | 30 | 30 | 1% | Dressel 2-4 | ||

| BSW | 24 | 228 | 10 | 4% | |||

| CGFCS | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | |||

| CGGLZ | 1 | 2 | 2 | <1% | |||

| CGMIC | 3 | 16 | 5 | <1% | 0.11 | 4% | Jar Cam 262 |

| COLB | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | |||

| GROG | 171 | 2361 | 14 | 42% | 2.06 | 68% | Platters Cam 21 A2, bowl Cam 212, jars Cam 249 Cam 258 G19 |

| GROGC | 82 | 2158 | 26 | 38% | 0.40 | 13% | Jar Cam 260 |

| GROGRF | 3 | 30 | 10 | 1% | 0.10 | 3% | Beaker Cam 116 |

| GROGRS | 3 | 76 | 25 | 1% | 0.08 | 3% | Bowl EF71 |

| GRS | 18 | 246 | 14 | 4% | 0.23 | 8% | Jar G23, lid |

| NGWF | 3 | 10 | 3 | <1% | |||

| NGWFS | 2 | 14 | 7 | <1% | Beaker Cam 113 | ||

| RED | 2 | 1 | 1 | <1% | |||

| SGSW | 4 | 36 | 9 | 1% | 0.06 | 2% | Platter f18R, bowl f29 |

| STOR | 6 | 168 | 28 | 3% | |||

| TNM | 2 | 30 | 15 | 1% | |||

| Total | 333 | 5643 | 3.04 |

This group is characteristic of pottery assemblages at the later end of Ceramic Phase 3. Most of the identifiable forms are mid-1st century types and the assemblage is dated to c. AD 45-55. Much of the imported fine ware is likely to be residual, except for the North Gaulish beakers and the samian. Roman fabrics are more in evidence, forming more than 12% of the assemblage by weight. Samian and Central Gaulish glazed wares are both present, but in general, the quantity of imports is in decline. There is Dressel 20 amphora, but wine amphoras are again represented by a single small sherd, and there is a smaller range of forms than previously in grog-tempered wares. The finer wares are again fragmentary. It should perhaps be noted that the small sherds of samian have been dated to AD 60-80.

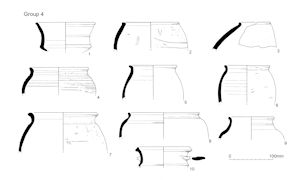

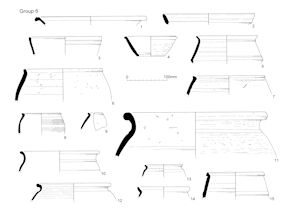

Fifteen groups, mainly from the central and southern settlement zones, with a total weight of 118kg and vessel rim equivalence (EVE) of 86.5, have been assigned to Ceramic Phase 4. Four of these groups, totalling 40.5kg and 32 EVE, are presented below. Ceramic Phase 4 is a period of continuity and change: sand replaces grog as the predominant tempering agent by the end of the phase, but many of the forms are little altered from Phase 3. Chelmsford provides a number of comparable assemblages; namely groups 1-3 (Going 1987, table 3) and the pottery from ditch K205 (Going 1992a, 96).

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASALA | 1 | 159 | 159 | 2% | Salazon | ||

| BSWM | 29 | 536 | 18 | 8% | 0.53 | 21% | Jar G20 |

| BUF | 1 | 2 | 2 | <1% | |||

| COLB | 9 | 44 | 5 | 1% | Flagon | ||

| ESH | 1 | 18 | 18 | <1% | |||

| GRF | 5 | 78 | 16 | 1% | 0.19 | 7% | Bowl EF57, jar G19 |

| GROG | 126 | 1680 | 13 | 26% | 0.92 | 36% | Platter A2, bowl C19, jars G19 G20 Cam 232 |

| GROGC | 30 | 1165 | 39 | 18% | 0.48 | 18% | Jars G45 Cam 259 |

| GRS | 10 | 182 | 18 | 3% | |||

| RED | 3 | 16 | 5 | <1% | |||

| STOR | 70 | 2650 | 38 | 41% | 0.46 | 18% | Jars EF126 EF178 G3 |

| Total | 285 | 6530 | 2.58 |

Pottery Group 15 is typical of the early part of Ceramic Phase 4. Measured by EVE, grog-tempered pottery predominates, though less so than in Phase 3; conversely, black-surfaced ware and storage jar fabrics form a larger proportion. A greater range of wheel-thrown sand-tempered pottery is also present in sandy and fine grey wares and buff ware, though still in relatively small proportions, while imports typical of the Late Iron Age are noticeably absent. A date of c. AD 50/55-60 is supported by the presence of the salazon amphora, as well as the remaining forms. The condition of the pottery is generally good, and the group is coherent with no obvious residual element.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSW | 73 | 858 | 12 | 5% | 0.90 | 7% | Jar G3, beaker H1 |

| BUF | 12 | 39 | 3 | <1% | |||

| COLB | 96 | 297 | 3 | 1% | 0.43 | 3% | Bowl, flagon |

| GRF | 72 | 274 | 4 | 1% | 1.40 | 10% | Bowl EF64, beaker H1 |

| GROG | 580 | 5430 | 9 | 26% | 6.15 | 44% | Platters Cam 21 A2, jars EF131 Cam 249 Cam 258 G3 G19 G20, beakers H1 H7, funnel N2 |

| GROGC | 240 | 5887 | 25 | 28% | 3.19 | 23% | Bowl C33, jars Cam 249 Cam 259 G45, lid K3 |

| GROGRS | 4 | 28 | 7 | <1% | 0.11 | 1% | Jar Cam 249 |

| GRS | 26 | 418 | 16 | 2% | 0.57 | 4% | Jar G20 |

| SGSW | 31 | 324 | 10 | 2% | 0.24 | 2% | Platter f15/17, bowls f29 f30, cups f27 Ritt.8 |

| STOR | 210 | 7470 | 36 | 35% | 0.73 | 5% | Jars Cam 270B Cam 271 G44 |

| TN | 2 | 15 | 8 | <1% | 0.06 | <1% | Platter Cam 13 |

| TR | 12 | 48 | 4 | <1% | 0.11 | 1% | Beaker Cam 112 |

| TRCG | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | |||

| Total | 1359 | 21092 | 13.89 |

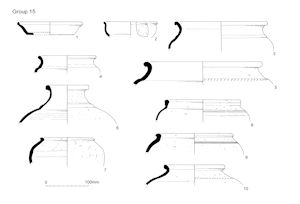

Grog-tempered pottery continues to dominate, but wheel-thrown, sand-tempered forms and fabrics are now common. Gallo-Belgic imports are barely represented and the forms present are among the latest to be produced. South Gaulish samian ware is present, with the range of forms falling within a date band of AD 45-80. The assemblage as a whole can probably be dated more closely to AD 55-65 because of the presence of two Colchester B brooches (SF1553, SF3281). Jars, beakers and platters are still the most common vessel classes, but bowls, cups and flagons are also much in evidence. There is also a grog-tempered ware funnel. The pottery is fragmentary and the small Central Gaulish sherd is residual.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSW | 202 | 5200 | 26 | 49% | 6.66 | 53% | Platter A2, bowls C27 Cam 214, jars G17 G19 G20, beaker H1, lid K6 |

| COLB | 24 | 346 | 14 | 3% | 1.00 | 8% | Flagon J3 |

| GRF | 19 | 1590 | 84 | 15% | 3.11 | 25% | Bowl C12, jars G20 G40 |

| GROG | 36 | 432 | 12 | 4% | 0.33 | 3% | Platter A2, jar G, lid K3 |

| GROGC | 15 | 620 | 41 | 6% | 0.03 | <1% | Jar |

| GRS | 50 | 1925 | 39 | 18% | 1.15 | 9% | Jars G17 G23 |

| HGG | 1 | 8 | 8 | <1% | |||

| IMIC | 3 | 8 | 3 | <1% | Beaker H1 | ||

| NGWF | 1 | 20 | 20 | <1% | |||

| SGSW | 2 | 12 | 6 | <1% | 0.14 | 1% | Platter f18 |

| STOR | 6 | 525 | 88 | 5% | 0.06 | <1% | |

| Total | 359 | 10686 | 12.48 |

This assemblage, dating to c. AD 70, demonstrates both typical and atypical aspects of the later part of this ceramic phase. Typically, grog-tempered pottery now forms a minor component, while wheel-thrown, sand-tempered pottery predominates. The assemblage is atypical in that it comprises eleven complete or near-complete vessels, with some of the remaining pottery being sufficiently preserved to gain complete profiles of another three vessels. The very low quantity of sandy grey ware is also unusual, and perhaps reinforces the view that most or all of the assemblage was deposited under special conditions, and cannot be regarded as a mundane rubbish deposit. There were a number of sherds in this feature that joined sherds in contemporaneous pit 20010; the mica-dusted beaker sherd from this feature is included for illustration here (Figure 247, no. 15).

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 1 | 12 | 12 | 1% | Dressel 20 | ||

| BSW | 55 | 556 | 10 | 25% | 0.34 | 11% | Platter A4, dish B8, jar, lid K3 |

| BUF | 6 | 12 | 2 | 1% | 0.11 | 4% | |

| BUFM | 2 | 60 | 30 | 3% | 0.03 | 1% | Mortarium D1 |

| COLB | 2 | 20 | 10 | 1% | |||

| GRF | 11 | 174 | 16 | 8% | 0.57 | 19% | Cup, jar G20 |

| GROG | 23 | 102 | 4 | 5% | 0.28 | 9% | Jar |

| GROGC | 5 | 148 | 30 | 7% | 0.03 | 1% | |

| GRS | 33 | 526 | 16 | 23% | 1.18 | 39% | Platter A2, jar G3, beaker H1, lid K6 |

| SGSW | 2 | 14 | 7 | 1% | 0.39 | 13% | Bowl f35 |

| STOR | 4 | 156 | 39 | 7% | |||

| VRWM | 2 | 394 | 197 | 18% | 0.08 | 3% | Mortarium D1 |

| Total | 146 | 2174 | 3.01 |

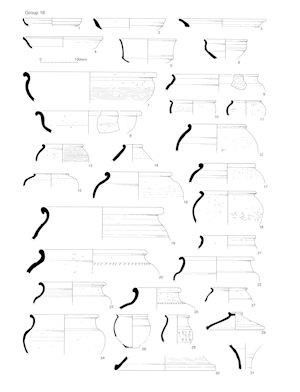

A large quantity of pottery was collected from pit 24013, and can be placed at the later end of Ceramic Phase 4. Grog-tempered pottery is present, but only in small quantities, while wheel-thrown, sand-tempered fabrics are predominant. The range of forms is wide. The Verulamium region white ware mortarium, with its deep and hooked flange, is one of the earliest products of that industry, dating to the pre-Flavian and early Flavian periods (Davies et al. 1994, 47). This, plus the samian bowl, which is dated no earlier than c. AD 70, provides an AD 70-80 date range for the deposition of the whole assemblage. As with KPG16, the condition of the group is poor, though fairly consistent. There is little that can easily be dismissed as residual, though the grog-tempered pottery could well be.

Seventeen groups from the central and southern zones, with a total weight of 864kg and vessel rim equivalence (EVE) of 55.19 have been assigned to Ceramic Phase 5. Three of these groups, totalling 200kg and 21 EVE, are presented below. Phase 5 covers a period of c. 45 years, but, despite this, there are few distinctions between individual pottery assemblages. Locally produced sand-tempered pottery predominates in all groups, and is accompanied by much smaller proportions of regional and imported wares. Groups 4 and 5 from Chelmsford provide comparable assemblages (Going 1987, table 3).

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSW | 29 | 615 | 21 | 30% | 1.18 | 55% | Jars G16 G17 G19 G20 G23 |

| COLB | 5 | 98 | 20 | 5% | |||

| GRF | 6 | 72 | 12 | 3% | Beaker | ||

| GROG | 3 | 36 | 12 | 2% | |||

| GROGC | 5 | 146 | 29 | 7% | Jar | ||

| GRS | 18 | 515 | 29 | 25% | 0.63 | 30% | Platter A2, jars G17 G20 |

| RED | 3 | 88 | 29 | 4% | 0.27 | 13% | Flagon J3 |

| SGSW | 1 | 10 | 10 | <1% | Platter f15/17 or f18 | ||

| STOR | 5 | 240 | 48 | 12% | 0.05 | 2% | |

| VRW | 6 | 254 | 42 | 12% | Flagon | ||

| TotaL | 81 | 2074 | 2.13 |

This assemblage dates to the early part of this ceramic phase, probably no later than c. AD 100. As expected for a group of this date, black-surfaced ware predominates with sandy grey ware forming a significant contribution, while the quantities of grog-tempered wares are small. The range of forms, mainly comprising high-shouldered jars, is typical. There is seemingly little or no obvious difference in the coarse wares between this group and those assigned to the end of Phase 4. The samian platter, however, dating to the late 1st century AD, provides the strongest evidence for pushing the date of deposition beyond AD 80. A coin of Domitian (SF7934) from an overlying fill does not conflict with this date. The condition of the assemblage is generally good, with nothing apart from the grog-tempered pottery that is obviously residual.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASALA | 2 | 150 | 75 | 3% | Salazon | ||

| BSW | 130 | 1230 | 9 | 24% | 2.01 | 46% | Platter A2, jars G17 G20 G23, beaker H1 |

| BUF | 23 | 76 | 3 | 1% | |||

| CGSW | 1 | 58 | 58 | 1% | Platter f18/31 | ||

| GRF | 1 | 2 | 2 | <1% | |||

| GROGC | 1 | 22 | 22 | <1% | |||

| GRS | 90 | 2205 | 25 | 42% | 2.06 | 48% | Jars G8 G17 G23, lid K |

| NKG | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | |||

| RED | 3 | 16 | 5 | <1% | 0.15 | 3% | Bowl C |

| SGSW | 3 | 28 | 9 | <1% | Platter f15/17 | ||

| STOR | 28 | 1540 | 55 | 29% | 0.11 | 3% | Jar G44 |

| Total | 283 | 5331 | 4.33 |

This group is dated to the early 2nd century, probably no later than c. AD 120. Composition is similar to that from earlier dated Roman period assemblages. Once again the samian evidence is fundamental, with the Central Gaulish platter providing an AD 100-120 date. The condition of the group is somewhat variable. Fabrics such as buff ware, North Kent grey ware and black-surfaced ware comprise small sherds, while sandy grey ware has a noticeably higher average sherd weight. Obviously residual pottery includes the grog-tempered ware, the amphora and South Gaulish samian platter, all of which are dated no later than AD 70.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB2 | 1 | 12 | 12 | <1% | 0.05 | <1% | Dish B2 |

| BSW | 537 | 6825 | 13 | 54% | 8.77 | 61% | Platter A2, dishes B1 B7, bowls C1 C6 C12, jars G16 G19 G20 G23, beaker H1, lid K3 |

| BUF | 8 | 54 | 7 | <1% | |||

| BUFM | 5 | 580 | 116 | 5% | 0.09 | 1% | Mortarium D1 |

| CGSW | 7 | 84 | 12 | 1% | 0.29 | 2% | Dishes f18/31R f18/31 or f31, bowl f37, cup |

| COLB | 46 | 615 | 13 | 5% | Flagon handle | ||

| GRF | 19 | 256 | 13 | 2% | 0.72 | 5% | Platter A2, jar, beaker H1 |

| GROG | 4 | 40 | 10 | 0.08 | 1% | Jar | |

| GRS | 125 | 2780 | 22 | 22% | 3.54 | 25% | Dish B7, jars G20 G23 G24 |

| LOND | 3 | 16 | 5 | ||||

| NKG | 5 | 136 | 27 | 1% | 0.34 | 2% | Platter A4 |

| NKO | 1 | 20 | 20 | <1% | 0.11 | 1% | Bowl |

| SGSW | 13 | 220 | 17 | 2% | 0.37 | 3% | Platters f15/17 f18, dish f36, bowl f30, cup f27g |

| STOR | 8 | 860 | 108 | 7% | |||

| VRW | 1 | 70 | 70 | 1% | Flagon handle | ||

| Total | 783 | 12568 | 14.36 |

Pottery Group 21, dating to c. AD 120/25, is the latest within this ceramic phase. It retains elements that date to the early 2nd century or earlier - platters, high-shouldered jars and North Kent wares - and yet includes pottery types, specifically BB2 and Central Gaulish samian, that take the date to the beginning of Phase 6. The BB2 dish has lattice decoration and a rim that is triangular in profile. Dishes of this description (Cam 37A) are dated to the Trajanic/Hadrianic period (Bidwell and Croom 1999, 469). None of the Central Gaulish samian pre-dates AD 120. The condition of the assemblage is fairly uniform. As for KPG20, there is less sandy grey ware than black-surfaced ware but, considering its higher average sherd weight, the sandy grey ware seems to be better preserved. The grog-tempered pottery is residual, as is some or all of the south Gaulish samian. The context also included 4g of intrusive late Roman Oxford ware derived from overlying features. This has been excluded from the tables.

Twelve groups, mainly from the northern settlement zone and with a total weight of 65.8kg and vessel rim equivalence (EVE) of 50.4, were assigned to Ceramic Phase 6. Four of these, totalling 52kg and 39 EVE, are presented below. As in Phase 5, assemblages comprise locally produced pottery, with varying, but always much smaller, proportions of regional and imported wares. This remains very much the pattern until the end of the Roman period. The groups below are comparable to a number of assemblages from Chelmsford, namely groups 6-8 (Going 1987, table 3) and the pottery from pit K90.2 (Going 1992a, 99-104).

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB2 | 30 | 509 | 17 | 2% | 1.16 | 6% | Dishes B2 B3 |

| BSW | 363 | 4267 | 12 | 20% | 7.57 | 38% | Platter A4, dishes B4 B7 B9, jars G16 G18 G23 G40, beaker H7, lid K3, miniature |

| BUF | 10 | 42 | 4 | <1% | |||

| CGSW | 16 | 148 | 9 | 1% | 0.60 | 3% | Dishes f31 f42, bowls f37 f78, cup f33 |

| COLC | 26 | 68 | 3 | <1% | 0.74 | 4% | Beaker H20 |

| GRF | 36 | 276 | 8 | 1% | 0.53 | 3% | Dish B10, jar G29, beakers H6 H34/H35 |

| GROG | 21 | 260 | 12 | 1% | Jar | ||

| GRS | 403 | 6185 | 15 | 30% | 7.52 | 37% | Dish B4, bowl C16, jars G20 G22 G23 G24 G29 G42, lid K3 |

| LESTA | 8 | 256 | 32 | 1% | 0.41 | 2% | Bowl C23 |

| NKG | 36 | 384 | 11 | 2% | 0.55 | 3% | Platter A4, beaker H6 |

| RED | 2 | 4 | 2 | ||||

| SGSW | 16 | 148 | 9 | 1% | 0.22 | 1% | Platter f15/17 or f18, dish f42, bowl f37 |

| STOR | 206 | 8530 | 41 | 40% | 0.53 | 3% | Jars G42 G44 G45 |

| VRW | 1 | 8 | 8 | <1% | |||

| VRWM | 1 | 212 | 212 | 1% | |||

| Total | 1175 | 21297 | 19.83 |

Ditch segment 10159 contained a large amount of pottery dating to c. AD 125-150. The assemblage includes a range of pottery typical of an early to mid-2nd century context, comprising bead-rimmed dishes, poppy-headed beakers, and flasks or narrow-necked jars. The presence of Colchester colour-coated ware, however, which was not widely distributed before AD 150/60, pushes the date of deposition towards the end of the offered date range. The folded H34/H35 beaker is unusual in this deposit; the type first appears in Chelmsford c. AD180 (Going 1987, 31). The condition of the assemblage is mixed, with a variable average sherd weight. The grog-tempered pottery and some of the South Gaulish samian, such as the f15/17 platter, are residual. The assemblage has been interpreted as a possible ritual deposit.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 5 | 644 | 129 | 10% | Dressel 20 | ||

| BB2 | 10 | 390 | 39 | 6% | 0.85 | 14% | Dishes B1B2 B4 |

| BSW | 68 | 1244 | 18 | 19% | 2.09 | 35% | Dish B4, jars G5 G9 G20 G29 G40 |

| CGSW | 18 | 184 | 10 | 3% | 0.66 | 11% | Dishes f18/31 f18/31R or 31R f31, bowl f37, cup f33 |

| COLB | 1 | 62 | 62 | 1% | Flagon neck | ||

| COLBM | 5 | 228 | 46 | 4% | 0.29 | 5% | Mortaria D1 D13 |

| COLC | 4 | 14 | 4 | <1% | 0.28 | 5% | Beaker H20 |

| COLSW | 6 | 44 | 7 | 1% | 0.18 | 3% | Dish f18/31 or f31 |

| GRF | 3 | 48 | 16 | 1% | |||

| GROGC | 1 | 54 | 54 | 1% | 0.06 | 1% | Jar |

| GRS | 34 | 706 | 21 | 11% | 0.73 | 12% | Dish B2/B4, jar G23, lid |

| HAWO | 2 | 34 | 17 | 1% | |||

| MWSRS | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | |||

| NKG | 9 | 56 | 6 | 1% | 0.19 | 3% | Beaker H6 |

| RED | 9 | 30 | 3 | <1% | 0.16 | 3% | Beaker ?H20 |

| STOR | 41 | 2720 | 66 | 41% | 0.46 | 8% | Jar G42 G45 |

| Total | 217 | 6464 | 5.95 |

Pit 7119 contained three fills, the pottery from two of which was quantified by EVE and has been amalgamated here. The assemblage provides a mid-2nd century date for filling, with the Central Gaulish samian recovered from the top fill, dating the final episode of deposition to around AD 155/60 or a little later. Mid-2nd century pottery groups at Elms Farm generally display a greater range of fabrics, particularly Colchester wares, than earlier dated contexts and KPG23 is no exception. While black-surfaced ware predominates, sandy grey ware forms a lower proportion measured by EVE than is usual. Conversely, BB2 forms a higher proportion. Some jar types, such as the high-shouldered G20, were residual at Chelmsford by the mid-2nd century, and are likely to be here also, as is the grog-tempered pottery.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 2 | 376 | 188 | 2% | Dressel 20 | ||

| BB1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | |||

| BB2 | 9 | 300 | 33 | 2% | 0.22 | 3% | Dish B4 |

| BSW | 145 | 1296 | 9 | 7% | 2.43 | 31% | Dish B4, jars G19 G23 G29 |

| BUF | 5 | 6 | 1 | <1% | |||

| CGSW | 13 | 112 | 9 | 1% | 0.50 | 6% | Cup f33, dishes f19/31R or f31R f31, bowl f37 |

| COLB | 4 | 76 | 19 | <1% | |||

| COLBM | 4 | 128 | 32 | 1% | |||

| COLC | 6 | 80 | 13 | <1% | 0.09 | 1% | Beaker H20 |

| COLSW | 5 | 36 | 7 | <1% | 0.22 | 3% | Cup f27 |

| EGSW | 1 | 64 | 64 | <1% | Dish f32 | ||

| GRF | 7 | 60 | 9 | <1% | Dish B2/B4 | ||

| GROG | 13 | 274 | 21 | 1% | 0.07 | 1% | Bowl |

| GRS | 190 | 2754 | 19 | 14% | 2.15 | 28% | Dishes B3 B7, bowl C1, jars G5 G19 G22 G23, beaker |

| GRSWSM | 1 | 132 | 132 | 1% | 0.08 | 1% | Mortarium D1 |

| MIC | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | |||

| NKG | 12 | 158 | 13 | 1% | 0.71 | 9% | Jar G40, beaker H5 |

| STOR | 151 | 13510 | 89 | 70% | 1.28 | 17% | Jars G36 G44 |

| Total | 570 | 19374 | 7.75 |

This assemblage, a composite of two fills from pit 9029, is dated c. AD 140 to c. AD 160. The date of deposition is likely to be at the later end of this range, or slightly beyond. The East Gaulish samian dish from the bottom fill is one of the latest pieces and dates from AD 160 onwards. The range of pottery present, such as bead-rimmed dishes and the roughcast colour-coated beaker, is very typical of this period. The large quantity of storage jar fabric is, however, unexpected. Assemblage condition is mixed. Fabrics such as black-surfaced ware and fine grey ware are represented by small sherds, and there is a quantity of clearly residual pottery (10% by EVE), notably the grog-tempered pottery and the high-shouldered G19 coarse ware jars.

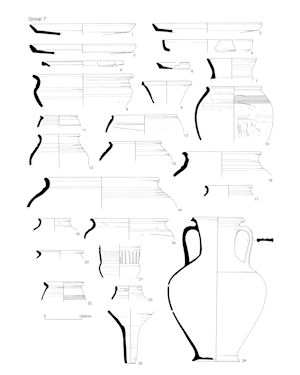

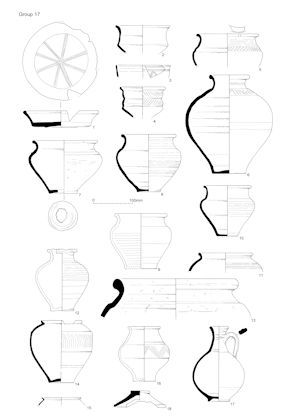

Six groups recovered from across the settlement, with a total weight of 46kg and rim equivalence (EVE) of 31.32, were assigned to Ceramic Phase 7. Three of these, totalling 35kg and 22.5 EVE, are presented below. These groups are comparable to Great Dunmow Group 464/820 (Going and Ford 1988, 61-6) and groups 9-16 from Chelmsford (Going 1987, table 3).

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSW | 105 | 2390 | 23 | 16% | 2.00 | 23% | Dish B1, jars G19 G23 |

| BUF | 2 | 60 | 30 | <1% | 0.09 | 1% | Bowl Cam 198 |

| CGSW | 2 | 20 | 10 | <1% | 0.06 | 1% | Dish f18/31 or 31, cup f33 |

| COLB | 2 | 6 | 3 | <1% | |||

| COLBM | 21 | 1845 | 88 | 12% | 1.11 | 13% | Mortaria D1 D2 D13 |

| COLC | 16 | 224 | 14 | 2% | 0.45 | 5% | Beaker H20 |

| COLSW | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | Bowl f37 | ||

| GROG | 4 | 56 | 14 | <1% | 0.13 | 2% | Jar G |

| GROGC | 1 | 52 | 52 | <1% | |||

| GRS | 286 | 8815 | 31 | 58% | 3.62 | 42% | Jars G5 G17 G22 G23 G24 G25, lid K6 |

| LOND | 1 | 10 | 10 | <1% | Bowl C | ||

| MIC | 1 | 20 | 20 | <1% | 0.12 | 2% | Bowl Cam 41 |

| MWSRS | 2 | 24 | 12 | <1% | 1.00 | 12% | Flagon J4 |

| STOR | 20 | 1775 | 89 | 12% | 0.07 | 1% | Jar G44 |

| Total | 464 | 15301 | 8.65 |

This group is dated to the late 2nd century AD. The offered date is supported by the presence of types produced at Heybridge during the late 2nd or early 3rd century, namely the D13 wall-sided mortarium, the G5 ledge-rimmed jar, and G25 jar (see Pottery production). Black-surfaced ware, always so dominant in previous groups, is relegated to second place after sandy grey ware, while, as expected, Colchester mortaria are present in greater quantity than in Ceramic Phase 6. The condition of the assemblage is generally good. Sherds are large, although there are perhaps fewer than expected rim sherds for a group of this size. The grog-tempered wares, London-type ware, and the mica-dusted bowl are all residual.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB2 | 9 | 412 | 46 | 8% | 0.83 | 17% | Dish B2 |

| BSW | 93 | 1552 | 17 | 32% | 2.21 | 45% | Dishes B2 B3, jars G9 G23 |

| CGSW | 13 | 745 | 57 | 15% | 1.04 | 22% | Dishes f31 f31R, bowl f37, cup f33 |

| COLC | 12 | 149 | 12 | 3% | 0.48 | 10% | Beakers H24 H35 |

| EGSW | 1 | 22 | 22 | <1% | Bowl f37 | ||

| GRF | 10 | 46 | 5 | 1% | 0.03 | 1% | Flagon J |

| GRS | 13 | 154 | 12 | 3% | 0.14 | 3% | Jar G |

| MIC | 2 | 5 | 3 | <1% | 0.05 | 1% | Beaker H |

| MWSRF | 3 | 42 | 14 | 1% | Flagon | ||

| STOR | 55 | 1801 | 33 | 37% | 0.03 | 1% | Jar G44 |

| VRW | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | |||

| Total | 212 | 4934 | 4.81 |

Pottery Group 26 is likely to have been deposited at the end of the 2nd century AD, possibly during the final decade. The bag-shaped H24 beaker, with barbotine decoration in the form of tendrils, is dated to after AD 190 at Chelmsford (Going 1987, 30); similar products from Colchester were first produced a little earlier (Bidwell and Croom 1999, 486). The assemblage includes six complete or near-complete vessels and so differs from similarly dated groups in this respect. This has resulted in several atypical elements immediately noticeable here. The proportion of sandy grey ware is far lower than usual, and there is, conversely, a higher proportion of fine wares. Composition, too, is unusual, with dishes and beakers, rather than jars, predominating. The condition of the pottery, apart from the complete vessels, is poor, with fabrics such as fine grey ware, mica-dusted ware and Verulamium region white ware represented by small sherds. These may have been deposited in a separate episode to the complete or near-complete vessels: a samian dish was one such vessel, which is not the sort of vessel typically used to lift water from a well. It is possible that this vessel, and others like it, formed part of a structured deposit.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSW | 40 | 343 | 9 | 2% | 1.16 | 13% | Jars G3 G5, flagon |

| BUF | 55 | 259 | 5 | 2% | 0.08 | 1% | Jar G26 |

| BUFM | 178 | 5579 | 31 | 37% | 2.59 | 29% | Mortaria D3 D11 |

| COLC | 2 | 10 | 5 | <1% | |||

| GRF | 142 | 737 | 5 | 5% | 0.35 | 4% | Dish B1, jar |

| GRM | 5 | 146 | 29 | 1% | 0.03 | <1% | Mortarium D11 |

| GROG | 13 | 130 | 10 | 1% | |||

| GROGC | 7 | 124 | 18 | 1% | |||

| GRS | 610 | 3710 | 6 | 24% | 3.51 | 39% | Dish B2/B4, jars G5 G25 |

| HAB | 6 | 48 | 8 | <1% | 0.09 | 1% | Dish B2/B4 |

| HAX | 1 | 28 | 28 | <1% | |||

| MWSRS | 5 | 20 | 4 | <1% | |||

| NVC | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | |||

| RED | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | |||

| STOR | 3 | 48 | 16 | <1% | |||

| UCC | 50 | 245 | 5 | 2% | 0.11 | 1% | Beaker |

| UPOT | 667 | 3725 | 6 | 25% | 1.13 | 13% | Dish B2/B4, beaker, flagon |

| Total | 1786 | 15162 | 9.05 |

Stoke-hole 1589 was serving kilns 1223 and 1618 during the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries AD. The group is an amalgam of the twenty contexts that comprised deposits within the stoke-hole. The pottery recovered was very likely deposited during the early 3rd century, and is therefore placed at the very end of Ceramic Phase 7. Buff ware mortaria and grey wares, being the principal fabrics of products fired in these kilns, predictably form the largest proportions within the assemblage. Black-surfaced ware also makes a significant contribution. Fine wares are present in small quantities. The condition of the group is generally poor. Much of the assemblage is burnt or very abraded and individual fabrics sometimes cannot be identified. The group is fragmented overall, although there is little besides the black-surfaced ware G3 jar and the grog-tempered pottery that must be residual.

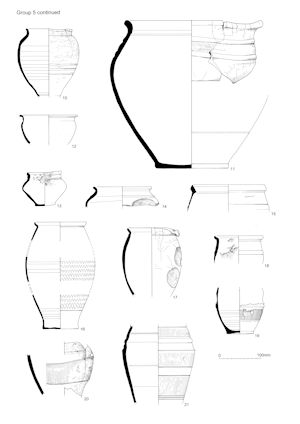

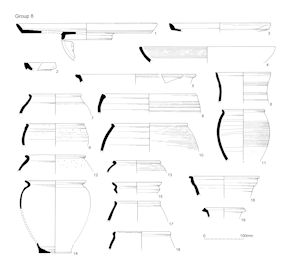

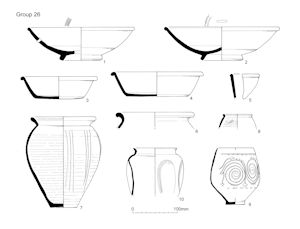

Recovered from the northern, southern and central zones of the settlement, five groups with a total weight of 28kg and rim equivalence (EVE) of 20 were assigned to Ceramic Phase 8. Three of these, totalling 13kg and 11 EVE, are presented below.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSW | 32 | 420 | 13 | 18% | 0.60 | 21% | Dish B4, jar G5, beaker H34 |

| BUF | 1 | 24 | 24 | 1% | 0.08 | 3% | |

| CGRHN | 7 | 30 | 4 | 1% | 0.14 | 5% | Beaker |

| CGSW | 4 | 102 | 26 | 4% | 0.14 | 5% | Platter f79 or Ludowici Tg, dish f18/31 or f31, bowl f37 |

| COLC | 1 | 2 | 2 | <1% | |||

| EGRHN | 1 | 1 | 1 | <1% | Beaker | ||

| GRF | 16 | 184 | 12 | 8% | 0.06 | 2% | Dish B4, beaker |

| GRS | 146 | 1303 | 9 | 55% | 1.66 | 58% | Dish B3, jars G5 Cam 218, beaker |

| MWSRS | 1 | 4 | 4 | <1% | |||

| NVC | 1 | 2 | 2 | <1% | |||

| SGSW | 1 | 2 | 2 | <1% | 0.01 | <1% | Platter f15/17 |

| STOR | 6 | 310 | 52 | 13% | 0.19 | 7% | Jar G44 |

| Total | 217 | 2384 | 2.88 |

This assemblage, dated to the early 3rd century AD is, in terms of the range of forms and general proportions of fabrics, similar in character to Ceramic Phase 7. The principal difference between them lies in the fine wares. There is a greater range here with the presence, albeit in small quantities, of Rhenish wares and Nene Valley and Colchester colour-coated wares. The condition of the assemblage is mixed, though generally poor. There is little that need be residual, except the 1st-early 2nd century Cam 218 jar and South Gaulish samian.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 2 | 95 | 48 | 1% | Dressel 20 | ||

| AGAUL | 1 | 80 | 80 | 1% | Gauloise 4 | ||

| BSW | 86 | 1770 | 21 | 22% | 1.12 | 16% | Dish B2/B4, jars G5 G24 |

| BUF | 5 | 84 | 17 | 1% | Face-pot | ||

| BUFM | 2 | 286 | 143 | 3% | 0.23 | 3% | Mortarium D11 |

| CGSW | 20 | 206 | 10 | 2% | 0.73 | 11% | Platter f18/31, dishes f31 f31R, bowls f36 f37, cups f33 f46 |

| EGSW | 1 | 14 | 14 | <1% | |||

| GRF | 30 | 540 | 18 | 6% | 1.06 | 15% | Dishes B2 B3 B4, jar G9 |

| GROG | 12 | 228 | 19 | 3% | 0.24 | 3% | Lid |

| GROGC | 4 | 114 | 29 | 1% | |||

| GRS | 101 | 1681 | 17 | 21% | 2.38 | 35% | Dish B2/B4, bowl-jar E5, jars G5 G24 G25, beakers H24 H34 |

| HAWO | 1 | 32 | 32 | <1% | 1.00 | 15% | Flagon |

| HAXM | 3 | 30 | 10 | <1% | |||

| LESTA | 1 | 10 | 10 | <1% | 0.11 | 2% | Bowl |

| NVC | 3 | 16 | 5 | <1% | |||

| RED | 17 | 200 | 12 | 2% | |||

| STOR | 46 | 2960 | 64 | 35% | Jar | ||

| VRGR | 9 | 146 | 16 | 2% | |||

| Total | 344 | 8492 | 6.87 |

Pottery Group 29 is dated to the first half of the 3rd century AD. The sandy grey ware is particularly typical of the period - the vessels present in this fabric are types produced into the 3rd century at Heybridge. Residual grog-tempered pottery is present, as ever. The stamped London-Essex bowl and Verulamium grey ware vessel are also residual. Assemblage condition is generally good; sherd size is reasonably uniform. Three sherds of Saxon pottery are intrusive and have been discounted.

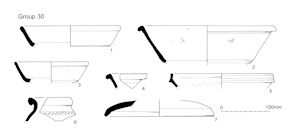

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AITAL | 2 | 824 | 412 | 32% | Dressel 1 | ||

| AMISC | 1 | 33 | 33 | 1% | |||

| BSW | 21 | 662 | 32 | 26% | 0.87 | 76% | Dishes B1 B3 B4 B5, beaker H34, lid K2 |

| EAM | 1 | 68 | 68 | 3% | |||

| EGSW | 1 | 18 | 18 | 1% | Dish or bowl | ||

| GROG | 1 | 2 | 2 | <1% | |||

| GRS | 20 | 442 | 22 | 17% | 0.20 | 18% | Jars G22 G25 G45 |

| HAX | 2 | 18 | 9 | 1% | |||

| NVC | 2 | 18 | 9 | 1% | Beaker H32 | ||

| NVM | 1 | 12 | 12 | <1% | 0.07 | 6% | Mortarium |

| RED | 1 | 38 | 38 | 1% | Bowl | ||

| STOR | 3 | 442 | 147 | 17% | |||

| Total | 56 | 2577 | 1.14 |

This small group is dated to the mid-3rd century AD. The presence of bead-rimmed dishes (B4) in association with incipient bead-and-flanged dishes (B5) and Nene Valley mortaria is typical of contexts dated to c. AD 260. Black-surfaced and sandy grey wares remain predominant. Fine wares are also present, but typically there is less diversity of fabric here compared to an early 3rd century group. For example, there are no imported fine wares, other than samian, or Colchester products. Despite the low number of rims, the condition of the pottery in this context is good. Sherd size is generally large, while some of the dish profiles can be reconstructed. Residual pottery is restricted to a single grog-tempered ware sherd.

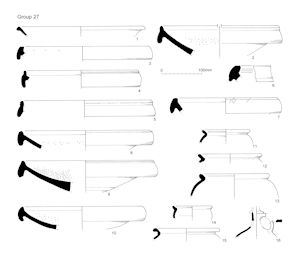

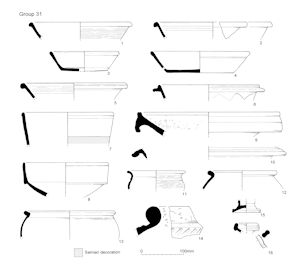

Recovered from across the whole of the settlement area, ten groups with a total weight of 49kg and rim equivalence (EVE) of 38 were assigned to Ceramic Phase 9. Four of these, totalling 27kg and 23 EVE and characteristic of the phase, are presented below.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 2 | 242 | 121 | 2% | Dressel 20 | ||

| AWINC | 2 | 42 | 21 | <1% | Dressel 2-4 | ||

| BB1 | 4 | 80 | 20 | 1% | 0.07 | 1% | Dish B6 |

| BB2 | 7 | 186 | 27 | 1% | 0.50 | 5% | Dish B3 |

| BSW | 383 | 2568 | 7 | 20% | 2.25 | 24% | Dishes B3 B4, bowl, bowl-jars E2 E5, jars G5 G24, beaker H34 |

| BUFM | 10 | 43 | 4 43 | 3% | 0.11 | 1% | Mortaria D3 D11 |

| CGFCS | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | |||

| CGSW | 13 | 112 | 9 | 1% | 0.13 | 2% | Platter f79R, dish f18/31 or 31, mortarium f45, cup f33, beaker f72 |

| EGSW | 13 | 260 | 20 | 2% | 0.11 | 1% | Dish f31R, bowls f30 f37 |

| GRF | 401 | 3197 | 8 | 25% | 1.54 | 16% | Dishes B2/B4 B3, jars G5 G24, beaker |

| GROGC | 16 | 390 | 24 | 3% | Jar | ||

| GRS | 185 | 2660 | 14 | 21% | 3.05 | 32% | Bowl-jar E2, jars G5 G24 G25 G42, beaker |

| HAB | 4 | 98 | 25 | 1% | 0.33 | 3% | Dish B3 |

| HAR | 27 | 435 | 16 | 3% | 0.88 | 9% | Dishes B2 B3, jar, beaker |

| HAWO | 3 | 42 | 14 | <1% | Jar | ||

| MWSRS | 4 | 26 | 7 | <1% | 0.31 | 3% | Flagon J3 |

| NKG | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | 0.06 | 1% | Jar |

| NVC | 3 | 18 | 6 | <1% | Lid K7 | ||

| NVM | 2 | 122 | 61 | 1% | 0.12 | 2% | Mortarium D14 |

| RED | 13 | 44 | 3 | <1% | |||

| RET | 2 | 10 | 5 | <1% | |||

| STOR | 51 | 1793 | 35 | 14% | 0.03 | <1% | Jar G44 |

| Total | 1147 | 12771 | 9.49 |

This large group is dated to the early part of Ceramic Phase 9, probably extending only a little beyond AD 260. The assemblage retains characteristics associated with early to mid-3rd century contexts: buff ware mortaria, bead-rimmed dishes, and ledge-rimmed jars. Other elements, such as the Nene Valley mortarium, Rettendon ware and BB1, undoubtedly push the date of deposition into the later 3rd century. As ever, black-surfaced and sandy grey wares dominate the assemblage. Of the remaining fabrics, only fine grey ware makes a significant contribution. The condition of the group is generally good, but fragmentary, and there is a relatively large proportion of residual pottery (around 8% by weight), including the grog-tempered ware, Central Gaulish samian, North Kent grey ware, and the white-slipped ring-necked flagon (J3). The group also contains an abraded sherd of later 4th century Alice Holt grey ware (excluded from the table), which must be intrusive.

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAET | 1 | 78 | 78 | 1% | Dressel 20 | ||

| BSW | 32 | 855 | 27 | 11% | 1.15 | 26% | Dishes B1 B2/B4 B6, jar G5, beaker |

| BUF | 4 | 66 | 17 | 1% | |||

| BUFM | 7 | 553 | 79 | 7% | 0.42 | 10% | Mortaria D3 D11 |

| CGSW | 6 | 78 | 13 | 1% | 0.24 | 5% | Dishes f18/31R or f31R f31, cup f33 |

| COLBM | 3 | 480 | 160 | 2% | 0.24 | 5% | Mortarium D11 |

| COLC | 3 | 26 | 9 | <1% | Beaker | ||

| GRF | 21 | 378 | 18 | 5% | 0.49 | 11% | Dish B2/B4, beaker H33 |

| GRS | 69 | 1245 | 18 | 16% | 1.48 | 34% | Dish B3, bowl-jar E2, jars G5 G9 G24 G42, beaker H34 |

| NVC | 3 | 36 | 12 | <1% | Beaker | ||

| NVM | 1 | 48 | 48 | 1% | |||

| OXWM | 1 | 124 | 124 | 2% | 0.09 | 2% | Mortarium D5 |

| RED | 6 | 114 | 19 | 1% | 0.08 | 2% | Jar G26 |

| RET | 2 | 32 | 16 | <1% | 0.11 | 3% | Jar G24 |

| STOR | 40 | 3490 | 87 | 46% | 0.09 | 2% | Jar G44 |

| Total | 199 | 7603 | 4.39 |

The pottery from fill of pit 6267 is dated to the late 3rd century. Although this group and KPG31 are broadly similar in terms of assemblage composition, KPG32 is likely to have been deposited later. This assertion is made on the basis of the bead-rimmed dishes. Here, they are represented by small abraded sherds and are probably residual. Other residual pottery includes the Central Gaulish samian, the Colchester colour-coated beaker, and probably the buff ware mortaria. The assemblage comprises relatively large sherds, and overall condition is good.

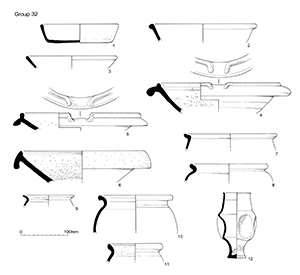

| Fabrics | Sherd no. | Weight (g) | Average sherd wt | % Weight | EVE | % EVE | Forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB1 | 14 | 575 | 41 | 9% | 0.40 | 5% | Dishes B1 B6 |

| BB2 | 1 | 50 | 50 | 1% | 0.07 | 1% | Dish B4 |

| BSW | 188 | 2316 | 12 | 35% | 2.81 | 34% | Jar G23 |

| CGSW | 3 | 52 | 17 | 1% | Dish f31R, bowl Curle 21 | ||

| COLC | 2 | 8 | 4 | <1% | Beaker | ||

| EGRHN | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | Beaker | ||

| EGSW | 1 | 6 | 6 | <1% | Bowl f37 | ||

| GRF | 8 | 208 | 26 | 3% | 0.13 | 2% | Dish B6, jar G24, beaker H32/H33 |

| GRS | 200 | 2474 | 12 | 37% | 2 | 38% | Dishes B1 B2 B5, jars G5 G9 G23, beaker H39 |

| HAB | 32 | 132 | 4 | 2% | 0.08 | 1% | Flask/beaker |

| NVC | 38 | 474 | 12 | 7% | 1.39 | 17% | Beakers H28 H41 |

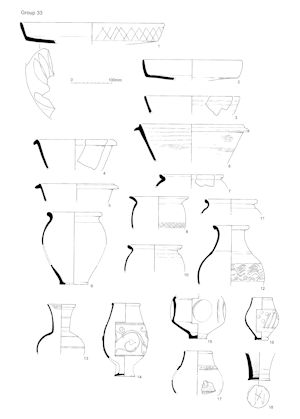

| RET | 14 | 332 | 24 | 5% | 0.26 | 3% | Jar G24 |