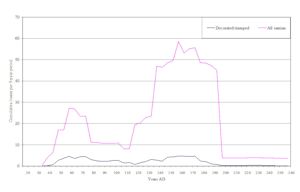

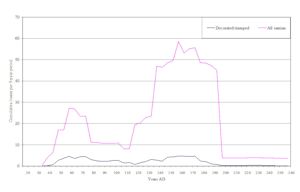

The total samian assemblage comprises 4937 sherds, weighing 79237g, and forms just 1.2% by weight of the total pottery recovered. The samian was identified and dated by Brenda Dickinson and catalogues of the stamps and decorated vessels were produced (see below). The Arretine ware (Italian-type sigillata) was isolated and subsequently identified and dated by Joanna Bird (see below). Figure 309 shows cumulative vessel losses at 5-year intervals. As part of the English Heritage-funded Samian Project, Steve Willis accessed the samian data in advance of publication and produced an overview of the trends at Elms Farm compared with a range of assemblages recorded elsewhere. The following report encompasses both sets of work.

Abbreviations

Conspectus = form type in Ettlinger et al. 1990

D = figure type in Déchelette 1904

O = figure type in Oswald 1936-7

OCK = second edition of the Corpus Vasorum Arretinorum (Oxé and Comfort 2000)

ORL = Der obergermanisch-raetische Limes des Römerreiches

Rogers = motif in Rogers 1974

Cite this as: Bird, J. 2015, The Italian-type terra sigillata, in M. Atkinson and S.J. Preston Heybridge: A Late Iron Age and Roman Settlement, Excavations at Elms Farm 1993-5, Internet Archaeology 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.1.bird

The Italian-type sigillata consists of twenty-five sherds representing a maximum of twenty vessels; eighteen platters, including seven examples of Conspectus form 12, and two cups. The majority of the pieces, including the single stamped base, are in a fine fabric with some colourless mica flakes visible in the section. Without analysis no certain source can be suggested for this fabric, which is a very pale brown or beige in colour, with a brownish tint to the slip. The material is mostly dated c. 15 BC-AD 10, with a few pieces that could date up to c. AD 20.

1. Three joining sherds from the floor of a large platter with rouletted circle and two-line radial stamp. The upper line of the stamp is almost completely lost, but may include the letter R; the lower line is probably complete, and reads TITI. Fill 20031, Pit 20030 (Group 248), Area L, Period 2B

Dr Philip Kenrick comments:

'The only such stamps for which I have radial examples are:

OCK 2224.2 LVCR/L.TIT Lucrio L. Titi of Arezzo (?), c. 20 BC+ OCK 2251.1-3 SEX/TITI Sex. Titius of Arezzo, c. 30-15 BC

My only initial offering for the fragment of line 1 was "..R" so Lucrio might be possible, but there is no facsimile for the type listed above for confirmation and I would be a little surprised if the stamp extended further to the left to accommodate the praenomen. The only other potential stamp with "..R" would be ANTER/TITI (OCK 2204, location undefined, c. 15 BC+), but I do not have either a radial stamp for him or identical facsimile/reading. Sex. Titius has more radial stamps, and might perhaps be possible.'

2. Platter, Conspectus form 12, and probably 12.3, but insufficient survives to be certain; diameter 300mm. Mid- to late Augustan. 4000 (Group 8021), unstratified, Area A1

3. Large (diameter approx. 460mm) platter, Conspectus form 12; cf. especially 12.1.3, though 12.1.2 is the only example illustrated of comparable size, may be the same vessel as 7148 below. Mid- to late Augustan. Fill 7134, Pit 7060 (Group 310), Area G, Period 2B

4. Floor sherd, large platter; may be same as 7134 above, and is certainly of the same date and origin. Fill 7148, Pit 7146 (Group 308), Area G, Period 2B

5. Platter base with bevelled foot and double groove on the floor, probably Conspectus form 12. Relatively dark reddish-orange fabric and slip, probably from an early Gaulish workshop. Mid- to late Augustan. Fill 7173, Pit 7174 (Group 853), Area G, Period 3

6. Platter, probably Conspectus form 12; diameter approx. 260mm. Mid- to late Augustan. Fill 7516, Stake-hole 7515 (Group 849), Area G, Period 3

7. Bevelled cup foot, too fragmentary to identify certainly, but cf. Conspectus forms 13 and, particularly, 14. The fabric may be one produced at Pisa, but the sherd is burnt. Mid- to late Augustan. Layer 5883 (Group 369), Area I, Period 3-4

8. Two sherds: i) platter floor fragment; ii) platter wall/floor sherd, probably as Conspectus 12.3.1. Both mid- to late Augustan. Fill 9585, Pit 9611 (Group 75), Area D, Period 2

9. Platter, Conspectus form 12, in a fine chalk-filled fabric. Mid- to later Augustan. Fill 10287, Pit 10288 (Group 303), Area F, Period 2B

10. Two joining sherds, small (diameter 180mm) platter, Conspectus form 12.2. Relatively coarse fabric, very micaceous, probably early Gaulish. Mid- to later Augustan. Fill 11277, Pit 11337 (Group 61), Area N, Period 2A

11. Large square foot from a platter (cf. Conspectus B1.6-10); the slip is almost completely lost. Augustan-Tiberian. Fill 8011, Pit 8012 (Group 296), Area E, Period 2

12. Four sherds: i) two sherds, probably from one platter floor; ii) floor sherd with at least one groove, from a large platter; slightly burnt; iii) platter floor sherd, burnt. All Augustan-Tiberian. Fill 9704, Pit 9792 (Group 288), Area D, Period 2B

13. Platter floor sherd. Mid-Augustan-Tiberian. Layer 9542 (Group 9016), Area D, unphased

14. Floor sherd, large platter; burnt. Mid-Augustan-Tiberian. Fill 14226, Pit 14225 (Group 36), Area L, Period 2A

15. Large (diameter 360mm) platter, Conspectus form 12.2; the fabric is rather pinker in tone than most of the material from the site. Mid- to late Augustan. Fill 20329, Pit 20481 (Group 42), Area L, Period 2A

16. Two small sherds, probably from one platter; the slip is mostly lost. Mid-Augustan-Tiberian. Fill 9011, Pit 8013 (Group 75), Area D, Period 2A

17. Conical cup fragment, form not identifiable, probably later Augustan-Tiberian. Fill 4497, Pit 4496 (Group 276), Area K, Period 2

18. Two sherds, probably the same vessel. Not terra sigillata but copying an Italian cup form with conical body and upright rim (cf. Conspectus form 23). The fabric is dark cream, with large inclusions of orange grog or haematite, and dense small mica flakes; the slip is thick, orange in colour but rather unevenly applied - perhaps deliberately, to give a marbled effect. The fabric suggests a Central Gaulish origin, the form a date in the early to mid-1st century AD. Layer 7445 (Group 871), Area G, Period 5; Fill 7453, Gully 7454 (Group 1349), Area G, unphased

Cite this as: Dickinson, B. 2015, The decorated ware and the potters' stamps, in M. Atkinson and S.J. Preston Heybridge: A Late Iron Age and Roman Settlement, Excavations at Elms Farm 1993-5, Internet Archaeology 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.1.dickinson

A maximum of 4560 vessels, which can be assigned to a pottery or area of production, were recorded. Fifteen sherds that were either impossible to attribute to a source, or were not necessarily samian, have been omitted from the statistics. The 4560 vessels are divided by type, as follows:

| Type | Vessel no. | Percentages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of whole | % of SG | ||

| SGBAN | 7 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| SGMN | 1 | < 0.1 | 0.1 |

| SGLG | 992 | 21.8 | 99.2 |

| % of whole | % of CG | ||

| CGMV | 221 | 4.8 | 7.5 |

| CGLZ | 2718 | 59.6 | 92.5 |

| % of whole | % of BR | ||

| BRPUL | 3 | 0.1 | 2.9 |

| BRCOL | 101 | 2.2 | 97.1 |

| % of whole | % of EG | ||

| EG | 16 | 0.4 | 3.1 |

| EGAR | 4 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| EGHB | 1 | < 0.1 | 0.2 |

| EGLM | 37 | 0.8 | 7.2 |

| EGRZ | 382 | 8.4 | 73.9 |

| EGTR | 77 | 1.7 | 14.9 |

Abbreviations: BR British; CG Central Gaulish; EG East Gaulish; SG South Gaulish;

AR Argonne; BAN Banassac; COL Colchester; HB Heiligenberg;

LG La Graufesenque; LM La Madeleine; LZ Lezoux; MN Montans;

MV Les Martres-de-Veyre; PUL Pulborough; RZ Rheinzabern; TR Trier

The decorated ware that could be relatively closely dated includes bowls with stamps of, or in the styles of, the following potters:

| Pre-Flavian | Flavian | Flavian-Trajanic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crestio | 1 | Calvus | 1 | Mercator i | 1 |

| Crestus | 1 | Memor | 1 | ||

| Felix i | 1 | ||||

| Martialis i | 1 | ||||

| Masclus | 1 | ||||

| Sabinus iii | 1 | ||||

| Trajanic | Hadrianic-E. Antonine | Hadrianic- Antonine | AD 150-180 | Mid-late Antonine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-2 | 3 | Acaunissa | 1 | Cettus | 10 | Albucius ii | 10 | Advocisus | 3 |

| X-3 (Drusus i) | 3 | Drusus ii | 1 | Criciro v | 1 | Albucius ii? | 2 | Banuus | 4 |

| X-4 (Igocatus) | 1 | Geminus iv | 1 | Docilis i | 1 | Cinnamus ii | 28 | Casurius | 4 |

| X-9 | 1 | Paternus iv | 1 | Cerialis ii - | 4 | Cinnamus ii? | 4 | Catussa | 1 |

| X-12 | 1 | Quintilianus i | 2 | Cinnamus ii group | Illixo | 1 | Censorinus ii | 3 | |

| Quintilianus I group | 2 | Laxtucissa | 1 | Cerialis v | 2 | ||||

| Sacer I group | 3 | Mammius | 1 | Do(v)eccus | 12 | ||||

| Secundinus ii | 1 | Secundus v | 3 | Iullinus ii | 1 | ||||

| Sissus ii | 1 | Secundus v? | 2 | Iullius ii? | 1 | ||||

| Tetturo | 1 | Iustus ii | 2 | ||||||

| X-6 | 5 | Paternus v | 4 | ||||||

| Paternus v group | 6 | ||||||||

| Paternus v group? | 1 | ||||||||

| Priscus iii | 1 | ||||||||

| Servus iv | 3 | ||||||||

| Servus iv? | 1 | ||||||||

| Early-mid-Antonine | Mid-Antonine | Later 2nd-1st half 3rd century | 3rd century | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tocca? | 1 | Mammilianus | 1 | Helenius ii | 1 | Afer iii | 1 |

| Dubitatus ii / Primanus v | 1 | ||||||

| Iulius viii | 1 | ||||||

| Iulius viii-Iulianus iii | 2 | ||||||

| Iulius viii-Iulianus iii? | 1 | ||||||

| Iulius-Lupus | 2 | ||||||

| Previncus | 1 | ||||||

| Victor v-Ianuco | 1 | ||||||

The most striking feature of the South Gaulish ware from La Graufesenque is that the f30 bowl form accounts for almost one quarter of the identified decorated ware and 37% of the commonest forms (these being bowls f29, f30 and f37). The cylindrical bowl f30 survived throughout the entire period of samian export, but normally makes only a modest showing against the more popular hemispherical f29 and f37. Most of the examples at Heybridge are Neronian and it is not impossible that they formed part of a single consignment. It is also curious that two complete bowls were buried together with a complete, but pierced, grog-tempered jar and a large lid. There are few other known instances of such an occurrence and no convincing explanation occurs (see also The structured deposition of pottery).

The globular jar, f67, is generally even rarer and the number found here (eleven (0.24%), with possibly three more), though modest, may seem worthy of mention.

The remaining eight South Gaulish pieces consist of a single vessel from Montans and seven from Banassac. First-century Montans ware is not particularly common in Britain, but small quantities have been noted in London and the west Midlands, particularly. The occurrence of Banassac ware is similarly sporadic, but rather more widespread, appearing on sites as far north as Carlisle and Old Penrith. The pieces found at Heybridge all belong to the first half of the 2nd century and it is not impossible that they arrived in a single consignment. The 1st-century assemblage also contained seven pieces of Lezoux ware, two of them decorated. This, again, does not occur in large quantities on any British site, apart from London, but its distribution is wide, and it has been noted on at least two sites in Scotland.

The samian supply to Heybridge diminished in the Trajanic period. This is not necessarily significant, as Trajanic ware from the Central Gaulish factory of Les Martres-de-Veyre was unevenly distributed in Britain, and a good many sites received noticeably less samian in the first two decades of the 2nd century than they did before or after. The same is apparent in the published samian from Colchester (Symonds and Wade 1999, 3 and 120). Increasing quantities of samian began to be discarded at Heybridge in the AD 120s with the arrival of Lezoux ware, but it was not until the early Antonine period that noticeably larger amounts were being discarded. This high level was maintained down to c. AD 180.

The bulk of the collection is 2nd century and so, as would be expected on a British site, consists mainly of Central Gaulish ware from Lezoux. This was supplemented by East Gaulish ware, particularly towards the end of the 2nd century and by British wares from Colchester and, probably, Pulborough. The 3rd-century supply is entirely East Gaulish. A notable aspect of the samian, which may again hint at the remains of a single consignment, is the popularity of the work of Cettus of Les Martres-de-Veyre, ten of whose bowls were found. Like some of the recovered plain ware from that factory, they are Hadrianic-Antonine in date.

The geographical position of Heybridge makes it a prime candidate to receive Colchester samian, and a maximum of 101 vessels was found. Only five of these were decorated. Unfortunately, the scarcity of comparable East Anglian assemblages makes it difficult to assess the importance of this find. The much smaller assemblage, of approximately 357 samian vessels recovered from Scole (Hartley and Dickinson 1977, 155-72) produced only 0.8% of the total vessels in Colchester ware, against 2.2% from Heybridge. This, of course, could be explained by its greater distance from the kilns. Colchester ware at Chelmsford was seemingly rare, amounting to just a trickle of sherds (Rodwell 1987b, 97). The other British pottery source whose wares almost certainly occur is Pulborough, represented by three vessels. The distribution of this pottery is confined mainly to Sussex, Hertfordshire and Essex, but occurrences are also known from Surrey, Norfolk (twice) and London, with one example as far afield as Sea Mills in Gloucestershire.

The earlier East Gaulish samian consists almost entirely of La Madeleine ware, which accounts for 7.2% of the East Gaulish assemblage. La Madeleine supplied samian to Britain in the Hadrianc and early Antonine periods and seems to have maintained a steady, if relatively modest, trade with the province. Also 2nd century are four vessels from the Argonne and single examples from Heiligenberg and, perhaps, Blickweiler. A larger proportion (14.9%), much of it 3rd century, was supplied by Trier, but the bulk of the East Gaulish ware (73.9%) comes from Rheinzabern and some of it is certainly 2nd century. A small proportion of the East Gaulish samian cannot be assigned to specific potteries.

Owing to the erosion of the sherds in much of this collection, it was only possible to detect cross-context joins between decorated pieces, though a few others were noted. No further work was done regarding cross-context joins since sherd links for the coarse pottery were only fortuitously recorded, because of the large volume of pottery involved.

The highest concentration occurs in the central zone of the settlement, with a marked decrease eastwards and northwards (Table 12).

| Settlement zone | Northern | Central | Southern | Hinterland |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % weight | 29% | 38% | 30% | 3% |

Distribution of the samian by area is shown in Table 13.

| Area | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | P | Q | R | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 9.1 | 3.8 | 8.8 | 7.5 | 21.2 | 10.8 | 6.4 | 10.3 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 2.1 |

The fluctuations in the pattern of accumulation of discarded samian is normal for a British settlement occupied throughout the period of samian import into the province, with the bulk of the assemblage consisting of South Gaulish and Lezoux ware, with lesser contributions from Les Martres-de-Veyre, East Gaul and other factories whose wares are uncommon in Britain.

A small quantity of Arretine ware, with a date range of c. 20 BC to AD 25, was found. Unlike some of the other pre-Roman settlements in the south and south-east where it occurs, there is no contemporary samian. The absence (with a single exception) of typologically Tiberian forms is striking and, indeed, there seems to have been no significant build-up of discarded samian before c. AD 50. It had reached its peak in the 1st century by c. AD 60-65 and by c. AD 80 the level had dropped noticeably and did not recover until the early Hadrianic period. If the trend suggested by the samian is to be believed, the settlement did not suffer at the hands of Boudicca, and the burnt sherds of relevant date are no more than might be expected in a random collection of this size.

Most of the sherds have been dated according to the reigns of emperors or dynasties, but it was possible to date much of the decorated ware and the identified potters' stamps on plain ware more closely, and this is likely to give a truer picture. Figures 309 and 310 shows the discrepancies caused by the use of two different methods and the danger of assigning wide date ranges to large volumes of sherds. While the 1st- and 2nd-century peaks coincide, there is a conflict in the early 2nd century, with the broader dating suggesting an upsurge in discards c. AD 120, and a date five years later by the decorated and stamped vessels. The latter is more likely to be correct, reflecting a time when the supply of Lezoux samian to Britain had got into its stride. Similarly, the start of the final decline in the supply is more likely to have begun c. AD 180, as suggested by the decorated ware and potters' stamps, than AD 200, by which time the export of Central Gaulish samian to Britain had almost ceased and the quantities of East Gaulish ware reaching the province were comparatively modest.

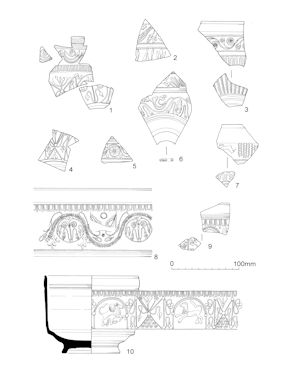

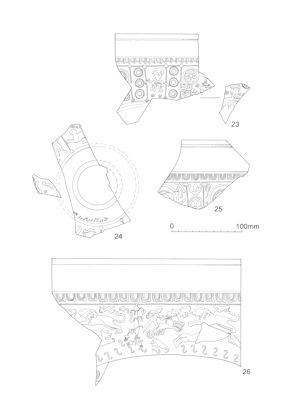

D1 Bowl f29, South Gaulish. The distinctive feature of this bowl is the band of rouletting on the central cordon. This would normally indicate a Tiberian product, but the coarseness of the rouletting suggests a rather later date and the formal arrangement of the decoration is not typical of the pre-Claudian period. The lozenge-shaped leaf in the lower zone, used by more than one mould-maker, is on f29 bowls from Camulodunum (Hawkes and Hull 1947, pl. xxvi, no. 13) and Hofheim (Knorr 1952, Taf. 76E), cf. also D10, below. c. AD 40-55. Layer 13498 (Group 600), Area I, Period 3B; Fill 13545, Pit 13893 (Group 176), Area J, Period 2B; Fill 13546, Pit 13894 (Group 3024), Area J, Period 3; Fill 13547, Pit 13549 (Group 404), Area J, Period 2B; Layer 13576 (Group 600), Area I, Period 3

D2 Bowl f29, South Gaulish. The details in the upper zone are all on a bowl of the same form from Camulodunum, dated to the Claudian period by Hull (Hawkes and Hull 1947, pl. xxv, no. 21). The bud in this zone is on bowls stamped by Licinus, from Wiesbaden (Knorr 1919, Taf. 45A) and Colchester (Knorr 1952, Taf. 63E), the latter from a mould stamped by Volus. The large trifid motif in the lower zone is on a bowl from Camulodunum (Hawkes and Hull 1947, pl. xxxvii, no. 1) and the decoration of the whole zone may be identical to that of another from the same site (Hawkes and Hull 1947, pl. xxiii, no. 17). c. AD 45-60. Layer 24243 (Group 3044), Area M, Period 3

D3 Bowl f29, South Gaulish. The trifid motif, astragalus scroll-binding and rosette in the spiral are almost certainly the same as on a bowl from Colchester, which may have some connection with Murranus (Dannell 1999, fig. 2.34, no. 477). c. AD 45-60. Fill 17258, Pit 17412 (Group 330), Area Q, Period 2B

D4 Bowl f29, South Gaulish. The decoration of the lower zone consists of alternating panels containing saltires, involving tulip buds and trifid motifs, and single-bordered medallions. c. AD 50-70. Fill 15786, Pit 15757 (Group 900), Area M, Period 3; Fill 15892, Post-hole 15891 (Group 9013), Area M, unphased

D5 Bowl f29, South Gaulish. The delicate scroll in the upper zone, with its eight-petalled rosette, hollow bud and chevron-and-beads suggests a range c. AD 50-70. Fill 7267, Pit 7266 (Group 2114), Area G, Unphased

D6 Bowl f29, South Gaulish, stamped OFCRESTI retr. (see S31, below). The decoration of the lower zone is precisely matched on an f37 bowl of M. Crestio from the Cala Culip (Cap Creus) wreck (Mees 1995, Taf. 36, no. 7). The plant in the upper zone is also on one of his f37 bowls, from Castleshaw. The boar in this zone is probably Hermet 1934, pl. 27, no. 41. c. AD 65-85. Pit 20120 (Group 2042), Area L, Period 2B

D7 Bowl f29, Central Gaulish. The series of wavy lines, also on D16 below, occur on an f29 bowl at Lezoux with an internal stamp of Acapusos and on an f37 bowl from Colchester (GBS A526). Another vessel from Colchester, perhaps a lagena (1.81 G2850), has the tongueless ovolos. The animal in the upper zone is almost certainly a stag. The coarse, micaceous fabric and matt orange glaze belong to the 1st-century range at Lezoux. c. AD 70-85. Fill 14805, Pit 14806 (Group 707), Area L, Period 3

D8 Bowl f30, South Gaulish, in the style of Masclus. The single-bordered ovolo with rosette tongue (Dannell et al. 1998, fig. 2, IA) is probably the one on a signed bowl from London (Mees 1995, Taf. 107, no. 3). All the other motifs are known on his signed bowls. The scroll, frilled leaves, corded ring and ten-petalled rosette are on an (unprovenanced) bowl in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (Mees 1995, Taf. 108, no. 1). The single medallion is on another bowl without provenance in Narbonne Museum (Fiches et al. 1978, fig. 14, no. 5), and the bud in the lower part of the medallion is on a bowl in a group of Claudio-Neronian samian found at Narbonne-La Nautique (Mees 1995, Taf. 113, no. 10). The dog and bird are not precisely identifiable. c. AD 50-65. Layers 14541, 14573, 14609 (Group 8005), unstratified, Area L

D9 Bowl f30, South Gaulish. The ovolo (Dannell et al. 1998, fig. 1, EE) occurs in association with motifs on f29 bowls stamped by a number of Claudio-Neronian and Neronian potters. It is on two bowls from La Graufesenque, one (Hermet 1934, pl. 73, no. 1) with the trifid motif and the chevron scroll (there used as an arcade), the other (Hermet 1934, pl. 73, no. 2) with the small rings. Though not strictly datable within the period c. AD 40-70, since the decoration of the f30 bowl is often archaic in style, this is most likely to be Neronian. Layer 5936 (Group 606), Area I, Period 3

D10 Bowl f30, South Gaulish, in the style of Martialis i. The ovolo (Dannell et al. 1998, fig. 1, Fdb) and lion with doe (Hermet 1934, pl. 25, no. 8) are on a signed bowl from Entraigues (Mees 1995, Taf. 103, no. 1). The trifid motif (Hermet 1934, pl. 14, no. 44), group of three (smaller) rosettes and, probably, the ten-petalled rosette are on a bowl from Usk with a mould-stamp of this potter (Mees 1995, Taf. 103, no. 4). The lion to left is a smaller version of Hermet (1934, pl. 25, no. 20), with a different tail, presumably added after the original was broken. The lozenge-shaped leaves are almost certainly the same as those on D1, above. c. AD 50-65. Layer 4148 (Group 732), Area K, Period 3

D11 Bowl f30, South Gaulish, in the style of Sabinus iii. The tongueless ovolo (Stanfield 1937, fig. 11, no. 24), polygonal leaf (Stanfield 1937, fig. 11, no. 90), outermost bud in the lower part of the scroll (Stanfield 1937, fig. 11, no. 58), innermost bud (Stanfield 1937, fig. 11, no. 86), larger striated spindle (Stanfield 1937, fig. 11, no. 61) and poppy-heads (Stanfield 1937, fig. 11, no. 73) are all known for Sabinus. The scroll, poppy-heads, spirals and the largest bud are all on a signed lagena from Rodez (Stanfield 1937, pl. xxi). c. AD 50-65. Layer 4148 (Group 732), Area K, Period 3; Layer 4518 (Group 8004), unstratified, Area K

D12 Bowl f30, South Gaulish, in the style of Masclus. The ovolo (Dannell et al. 1998, fig. 2, LL) and pointed leaf are on a signed bowl from Augst (Mees 1995, Taf. 110, no. 3), the arcade on one from La Graufesenque (Mees 1995, Taf. 109, no. 1) and the astragalus pillar on one from Richborough (Mees 1995, Taf. 111, no. 2). c. AD 50-65. Fill 8796, Pit 25221 (Group 663), Area P, Period 3

D13 Bowl f30, South Gaulish. The unusual leaf occurs on an f30 bowl from Aislingen (Knorr 1919, Taf. 95J). The decoration is also unusual in having saltires in adjacent panels. c. AD 50-65. Fill 20483, Pit 20199 (Group 336), Area L, Period 2B

D14 Bowl f30, South Gaulish. The lower zone features a large winding scroll with a chevron arcade in the lower concavity, containing a composite motif consisting of a beaded column supporting spirals and a trifid motif, and with tendrils with tulip buds springing from its base. Such arrangements are typical of the Neronian period. c. AD 60-80. Fill 4039, Pit 4008 (Group 756), Area K, Period 3

D15 Bowl f30, South Gaulish. The ovolo (Dannell et al. 1998, fig. 2, SE) appears on bowls with mould-stamps of Mommo and signatures of Memor, Primus iv and Tetlo. It occurs with the vertical panel of trifid motifs on a bowl from Colchester (Dannell 1999, fig. 2.29, no. 424), attributed to Memor. A slightly different inverted bifid motif was used by Primus iv, on a signed bowl from Camelon. The stag is on a signed f29 bowl of Mommo from La Graufesenque (Mees 1995, Taf. 147, no. 7). c. AD 70-90. Fill 10778, Ditch 25244 (Group 360), Area F, Period 3

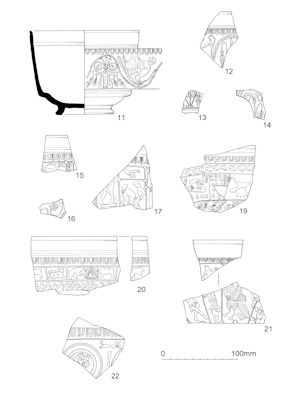

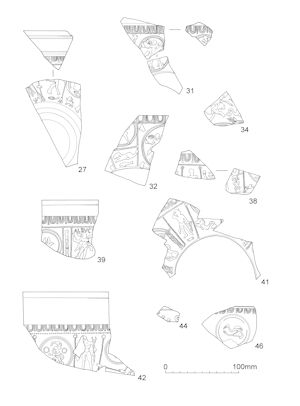

D16 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The coarse wavy-line border is matched on a 1st-century Lezoux f29 bowl (D7, above). The leaf is perhaps the prototype for a range used at Lezoux in the Hadrianic and Antonine periods (Rogers G200-205). c. AD 70-110. Fill 20011, Pit 20010 (Group 707), Area L, Period 3

D17 Bowl f30, South Gaulish. The trident-tongued ovolo has not been recognised on stamped or signed bowls, but it, and the style of the decoration, suggest Flavian-Trajanic date. The couple in the first panel (O.374) are on a bowl from Aquileia (Knorr 1910a, Taf. VI, no. 3) and, unprovenanced, on one in Stuttgart Museum (Knorr 1910b, Taf. 1, no .8), which also shows the same column (Hermet 1934, pl. 16, no. 48). The erotic group (a larger version of Oswald, pl. xc, C) is on a bowl from Heidenheim (Knorr 1910a, Taf. VI, no. 1). The bird is probably Hermet (1934, pl. 25, no. 80). Oswald attributed the bowls from Heidenheim and Aquileia to Banassac because they have an ovolo which is known to have been used there, but it was also used at La Graufesenque, and the decoration points to manufacture there. c. AD 85-110. Fill 5146, Pit 5147 (Group 409), Area J, Period 3

D18 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Drusus (X-3) of Les Martres-de-Veyre. The decoration includes a blurred trifid motif impressed horizontally, followed by a tripod (Rogers Q15), over a wreath composed of anchor motifs (Rogers G395). For the wreath and tripod, see a bowl from London in the style of this potter (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 10, no. 121). c. AD 100-120. Fill 9344, Gully 9343 (Group 3063), Area D, unphased

D19 Bowl f37, from the South Gaulish factory of Banassac. The kneeling stag is a common figure-type, used at both La Graufesenque and Banassac and produced in many variants. There is no precise parallel for this one in the range illustrated by Hofmann (1988, 148, nos 217-221). Similarly, the lion to right is close to type 204, but is not exactly the same. The leaf, which is used both in the basal wreath and (with the tip only) as a filler, may be the same as one on a bowl from Banassac, where the wreath is formed by overlapping impressions of the base of the leaf, instead of its upper part. The ovolo and the upper wreath are too blurred to be attributable. The fabric and glaze of this small bowl make attribution to Banassac secure, despite the lack of parallels for the details. c. AD 120-150. Layer 4166 (Group 8004), Area K, unphased; Fill 4266, Post-hole 4265 (Group 3034), Area K, Period 3; 7000, unstratified, Area G

D20 Bowl f37, South Gaulish (Banassac). The ovolo is probably the one most often used by the Natalis Group, which appears on a bowl from Cannstatt with what are probably the same arrow-head motifs (Knorr 1905, Taf. X, no. 7). The animals are a bear to right (Hofmann 1988, 150, no. 261 and a boar to left (Hofmann 1988, 149, no. 238). The bear is on a bowl from Straubing by one of the Natalis group. The chevron wreath is not precisely paralleled, but many similar examples occur in the work of these potters. c. AD 100-150. Fill 10182, Ditch 25245 (Group 361), Area G, Period 3

D21 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Drusus of Lezoux. The rosette-tongued ovolo is not closely identifiable. The Vulcan (D.39 = O.66), slave (D.374 = O.647), dancer (O.363 variant) with lantern (Rogers Q65) and leafy column (a smaller version of Rogers Q5) are on bowls with mould-signatures from, respectively, Colchester (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 88, no. 1), Chester (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 88, no. 3), Southampton (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 88, no. 8) and Salzburg (von Koblitz 1926, Taf. III, no. 4). The eagle (not in D. or O.) is on an f30 bowl at Castleford, from a pottery shop destroyed by fire in the AD 140s (Dickinson and Hartley 2000, fig. 27, no. 518). On the Heybridge piece it apparently holds a lizard in its beak. The six-beaded rosette (Rogers C278) is Drusus's commonest one. c. AD 125-145. Fill 5146, Pit 5147 (Group 409), Area J, Period 3

D22 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The ovolo (Rogers B109), dog (O.1926A) and small medallion inside a larger one are all present in the work of Catussa. The medallions are on bowls and moulds with stamps of Rogers's Catussa II, which sometimes also carry mould-signatures of Gemenus (Rogers 1999, pl. 43). The dog is on a bowl from Lezoux with a mould-signature of Catussa and a mould-stamp of Cantomallus. The ovolo is on a signed mould of Rogers's Catussa I (1999, pl. 27, no. 2). It seems from the connections between the styles of Catussa I and II that they represent the work of two mould-makers working for the same man. The tree (Rogers N9) and the other motif (perhaps the obelisk Rogers P68) are not recorded for either style. c. AD 160-190. 4000, unstratified, Area A1

D23 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The mould-signature, ]an[ retr., upside down below the decoration, almost certainly belongs to Ianuaris i. Although the seated figure (D.527 = O.913) and the Pan-mask (D.675 = O.1214) are not known on signed bowls, all the motifs occur on signed bowls of Ianuaris, and the use of astragali (Rogers R7) placed diagonally across the borders is typical. The details are: single-bordered ovolo (Rogers B28), wavy-line borders (Rogers A24), eight-petalled rosette in a single medallion (Rogers C6), eight-beaded rosette (Rogers C281), beaded ring (Rogers C290) and leaf motif (Rogers L12). The borders, beaded rosettes, astragali and beaded rings in vertical series are on a bowl from Carlisle (Stanfield and Simpson 1990, pl. 170, no. 4) and the rosette in a medallion is on one from York. c. AD 125-150. Layers 24058 and 24138 (Group 8006), Area M, unphased

D24 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, with mould-signature Tetturo... retr., upside down below the decoration. The details include: Pan (D.419 = O.717), putto (D.204 = O.394), leopard (D.969 ter = O.1564) five-petalled rosette (Rogers C120) and wavy-line borders (Rogers A26). The cornucopia is almost certainly Rogers U247, which occurs on a bowl in Tetturo's style in a pit at Alcester filled in the AD 150s (Hartley et al. 1994, fig. 50, no. 275). The festoon, a smaller version of Rogers F16, without the inner border, is on a bowl in his style from Corbridge. For further discussion of the potter, see S124, below. c. AD 130-160. Fill 20020, Pit 20019 (Group 711), Area L, Period 4

D25 Bowl f37, East Gaulish (La Madeleine). The ovolo (Ricken 1934, Taf. VII, C) appears on bowls from Camelon and Mumrills. The leaves consist of inverted trifid motifs (Ricken 1934, Taf. VII, no. 14) with added stems. Other details known to have been used at La Madeleine comprise a smaller trifid (Ricken 1934, Taf. VII, no. 24), acanthus (Ricken 1934, Taf. VII, no. 25) and festoon with acorn terminals (Ricken 1934, Taf. VII, no. 51). c. AD 130-160. Cleaning layer 5603, Area I

D26 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Cettus of Les Martres-de-Veyre. The ovolo and leaf (Rogers J144) are on a signed bowl from Les Martres (Terrisse 1968, pl.xx, no. 526) and the hare (O.2061) is on a bowl from Silchester with a mould-stamp in the decoration (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 141, no. 2). All the other details are on bowls, or moulds, in his style. They are: Apollo and chariot (not in D. or O.; Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 141, no. 9, from Les Martres), small bear, D.820 = O1627 (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 141, no. 16, from London), large bear, D809 = O.1595 (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 144, no. 57, from Carlisle), lion and panther (D.766 = O.1450, D.809 = O.1570; both on a mould in Moulins Museum), 'tree' (Rogers Q5), on a bowl from Corbridge (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 143, no. 35) and medallion below the decoration, on a bowl from Carlisle (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 144, no. 57). The elongated, reversed S-motifs are extremely rare for Cettus, but occur on a bowl from Silchester. c. AD 135-160. Cleaning layer 5617 (Group 8002), Area I

D27 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Cettus of Les Martres-de-Veyre. The ovolo and bunch of grapes seem not to have been recorded for him before. The decoration includes a Pan (D.419 = O.717), as on a signed bowl from Colchester (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 141, no. 4) and centaur (D.436 = O.745), as on a bowl in his style from Leicester (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 142, no. 33). The large trifid motif (Rogers G13) is on a bowl from Corbridge (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 142, no. 23) and the small trifid (Rogers G340), which he rarely used, is on a bowl from Mumrills (Hartley 1961, fig. 80, no. 54). For the use of an astragalus across a panel border, see Stanfield and Simpson (1958, pl. 141, no. 14, from Corbridge). c. AD 135-160. Fill 9071, Ditch 9070 (Group 778), Area D, Period 3

D28 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Cettus of Les Martres-de-Veyre. The ovolo (Rogers B96) and a lion to left are on a bowl in his style from London. c. AD 135-160. Layer 5877 (Group 600), Area I, Period 3

D29 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Divixtus i. A panelled bowl, with 1) Double festoon or medallion, over a crouching panther (D.799 = O.1518), 2) Double festoon or medallion, over a small double medallion. The profusion of festoons and medallions and his typical ring-terminals (Rogers C132) make attribution to Divixtus certain, see Stanfield and Simpson (1958, pl. 116, no. 10, from Corbridge). c. AD 150-180. Fill 9444, Ditch 9434 (Group 777), Area D, Period 3

D30 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Divixtus i. A seated Abundance (D.472 = O.801) and a caryatid (D.656 = O.1199), in adjacent panels, are on stamped bowls from Corbridge (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 116, no. 17 and no. 10, respectively). Both bowls have his single-bordered ovolo with beaded tongue (Rogers B12). c. AD 150-180. Spread 7457 (Group 1323), Area G, unphased

D31 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The ovolo (Rogers B143), with straight line below, is on a bowl from Great Chesterford with a mould stamp of Secundus v (Simpson and Rogers 1969, fig. 2, no. 4). The Cupid with torches (D.265 = O.450) is on a stamped bowl from Toulon-sur-Allier and the goat (D.889 = O.1836) is on one from York. The warrior (D.117 = O.188) is on a bowl with the same ovolo, attributed by Rogers (1999, pl. 80, no. 21) to Pugnus, but more likely to be by Secundus. c. AD 150-180. Fill 20020, Pit 20019 (Group 711), Area L, Period 4

D32 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The ovolo (Rogers B223) is associated mainly with Cinnamus ii, but it appears, usually with a straight line below, on bowls in the style of Secundus v. The figure in the large medallion is a Cupid with torches, as on D31, above. The motif in the corner of this panel is probably the tail of a small dolphin (D.1057 = O.2401), which occurs on a stamped Secundus bowl from Great Chesterford (Simpson and Rogers 1969, fig. 2, no. 4). The figure in a festoon in the top of the panel containing a crouching lion (D.753) and a supine figure (D.553 = O.939) is almost certainly an Amazon (D.154 = O.243), which occurs on the same bowl. The supine figure occurs, with the ovolo and dolphin, on a bowl which is almost certainly by this potter. c. AD 150-180. Fill 10296, Ditch 10406 (Group 838), Area G, Period 5; Fill 16083, Well 6280 (Group 531), Area H, Period 3

D33 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, with mould-stamp [CIN]NAMI retr.; Cinnamus ii of Lezoux, Die 5b. The panels include; 1) An ornament with leaves and dolphins (Rogers Q6), 2A) Double festoon, probably containing a bird, 2B) A dancer (O.819A, with broken left hand), 3) The potter's stamp and a triple leaf (Rogers L11), 4) A double-bordered medallion, containing a Pan (D.419 = O.717). c. AD 150-180. Layer 10310 (Group 1312), Area F, unphased

D34 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. A freestyle bowl in the style of Cinnamus ii, with a stag (D.852 = O.1720), lion (perhaps not previously recorded) and dolphin (D.1050 = O.2382). The corn-stook which is exclusive to Cinnamus (Rogers N15) occurs on a stamped bowl from London, with the stag (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 163, no. 70). He is also known to have used the dolphin. c. AD 150-180. Fill 7154, Pit 7169 (Group 4048), Area G, unphased

D35 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The ovolo (Rogers B145) was used by Carantinus, Cinnamus ii and Illixo. As there is apparently a beaded border below it, the bowl is most likely to be by Cinnamus. c. AD 150-180. Cleaning layer 8239 (Group 8013), Area E

D36 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. A panelled bowl, with 1) Minerva (a variant of D.77 = O. 126), owl (D.1020 = O.2331) and a trifid motif (Rogers H109), 2) An erotic group (a smaller version of Oswald, pl. xc, B). This is almost certainly by Cinnamus ii, who is known to have used all the details. c. AD 150-180. Cleaning layer 8239 (Group 8013), Area E

D37 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The ovolo (Rogers B182) is one of Cinnamus ii's less-common ones. The lower concavity of a winding scroll contains a kneeling stag (O.1704A) over an acanthus (Rogers K12), in a double medallion. The upper concavity has a polygonal leaf (Rogers J89) and another leaf (Rogers H13). The last is on a stamped bowl from London (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 161, no. 53) and all the other details, except for the polygonal leaf, are on another bowl from London (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 159, no. 25). c. AD 150-180. Fill 9444, Ditch 9434 (Group 777), Area D, Period 3

D38 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The ovolo (Rogers B85) appears on bowls in the styles of potters belonging to both the Cinnamus ii and Paternus v groups. This piece has links with the former, occurring on a stamped bowl of Cinnamus from Le Mans (Rogers 1999, pl. 32, no. 50a) and on one from Toulon-sur-Allier, by Secundus v. The figure-types are a philosopher (D.523 = O.905) and, probably, a dog (O.1974A), both known for Cinnamus. The candelabrum is made up of two elements which he used on stamped bowls, the dolphins on a basket (Rogers Q58; Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 159, no. 26, from London) and the top part (Rogers Q43; Walke and Walke 1968, Taf. 36, no. 1, from Gauting). The six-beaded rosette (Rogers C278) is on a bowl in his style from Cambridge and the cornucopia (Rogers U245) is on one from Caerleon. On balance, therefore, this bowl is more likely to be by Cinnamus than Secundus, but the range will be c. AD 150-180, in either case. Cleaning layer 5617 (Group 8002), Area I

D39 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, with mould-stamp in the decoration, ALBVC[I] (see S10, below). The details, a ring-tongued ovolo (Rogers B107), Cupid with torches (D.265 = O.450), bird (D.1010 = O.2316) and a baton (Rogers P3) have all been previously recorded for Albucius. c. AD 150-180. Layer 7073, Area G, unphased; Fill 7119, Pit 7118 (Group 852). Area G, Period 3

D40 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Albucius ii. Two sherds each show a panel, not necessarily adjacent, as follows: 1) Jupiter (D.4 = O.3), as on a stamped bowl from London (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 120, no. 5), 2) Venus (D.204 = O.338), apparently exclusive to Albucius, and appearing on a bowl from Bregenz (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 121, no. 16). c. AD 150-180. Fills 17188 and 17332, Post-hole 17230 (Group 942), Area Q, Period 3

D41 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. A bowl in the style of Iullinus ii, with his smallest ovolo (Rogers B164). The figure-types include an Apollo (D.45 = O.77) and a dolphin (O.2394A), neither of which seems to have been recorded for Iullinus before. The pillar supporting the arcade (Rogers P21) is on a stamped bowl from Lezoux (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 125, no. 1). c. AD 160-190. 7000, unstratified, Area G; Fill 7071, Pit 7072 (Group 868), Area G, Period 4; Fill 7274, Gully 7273 (Group 1345), unphased

D42 Bowl f37, Central Gaulish, in the style of Censorinus ii. The layout of the decoration is typical of his work, particularly the use of an astragalus border (Rogers A10) below the ovolo (here Rogers B105) and of horizontal astragali to join borders, as on Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 102, no. 11, from Corbridge. The motifs, a nine-petalled rosette (Rogers C194), column (Rogers P3) and astragalus (Rogers R7) are all known for Censorinus. The seated figure (D.527 = O.913) and the Mercury (D.289 = O. 529) seem to be unrecorded for him. c. AD 160-190. Fill 13818, Gully 13739 (Group 615), Area I, Period 3; Fill 13887, unstratified, Area J

D43 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The ring-tongued ovolo (Rogers B103) and zigzag border (Rogers A24) were used in conjunction by Martio i (Rogers's Martio II; cf. Rogers 1999, pl. 71, no. 5). c. AD 160-190. Fill 20013, Pit 20012 (Group 707), Area L, Period 3

D44 Bowl f37, Colchester ware. This appears to be in the style of Hull's Potter B, on whose moulds the rosette (1963, fig. 40, no. 70) and the roundels (Hull 1963, fig. 40, no. 79) appear. See figs 35, no. 8 and 36, no. 5, respectively. The border of squarish, separated beads seems to be a new detail for him. Potter B seems to have no connections with the group of East Gaulish potters who migrated to Colchester in the early Antonine period, and he is almost certainly later than them. c. AD 160-200? Fill 7123, Pit 7122 (Group 868), Area G, Period 4

D45 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, East Gaulish (Argonne). The surface of the bowl is heavily eroded, but a row of lions can be seen, with other animals below. A basal wreath is composed of opposed bifid motifs (Oswald 1945, fig. 6, LVII), which occur on two bowls from Lavoye with mould-stamps of Tocca (Oswald 1945, fig. 9, no. 35-6). c. AD 140-180? Layer 9454 (Group 8012), Area D, unphased.

D46 Bowl f37, East Gaulish (Rheinzabern). A small bowl, probably in Style II of Belsus, though the details were all used by other contemporary potters. The ovolo (Ricken and Fischer 1963, E26), double medallion (Ricken and Fischer 1963, K20a) and stork with snake (Ricken and Fischer 1963, T221) are on a stamped bowl from Rheinzabern (Ricken 1948, Taf. 110, no. 8). c. AD 170-230. Fill 16083, Well 6280 (Group 531), Area H, Period 2

D47 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, East Gaulish (Rheinzabern). The ovolo (Ricken and Fischer 1963, E7) and a leaf (Ricken and Fischer 1963, P79) are on a stamped bowl of Helenius (Ricken 1948, Taf. 175, no. 18). c. AD 170-240. Fill 8807, Pit 8748 (Group 44), Area P, Period 2A

D48 Bowl f37, East Gaulish (Rheinzabern). The details, a dolphin (Ricken and Fischer 1963, T194a), rosette (Ricken and Fischer 1963, O48) and corded border (Ricken and Fischer 1963, O248) were used by several Rheinzabern potters, but only Mammilianus seems to have used them all, and so the bowl is tentatively attributed to him. For the rosette and border, see a stamped bowl (Ricken 1948, Taf. 122, no. 1). The dolphin is on a bowl in his style (Ricken 1948, Taf. 123, no. 16). c. AD 180-240. Fill 7267, Pit 7266 (Group 2114), Area G, Period 2B

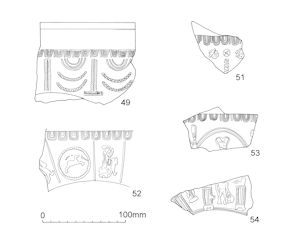

D49 Bowl f37, East Gaulish (Rheinzabern), with mould-stamp of Pervincus (S65). The ovolo (Ricken and Fischer 1963, E33) is on a bowl with the same stamp from Rheinzabern (Ricken 1948, Taf. 240, no. 10). The leaf (Ricken and Fischer 1963, P16) and the triple festoon (Ricken and Fischer 1963, O133) are on a stamped bowl from Heddernheim (Ricken 1948, Taf. 238, no. 2). The beaded festoon is similar to ones known for him. c. AD 200-240. Cleaning layer 5602 (Group 8002), Area I; Layer 13568 (Group 600), Area I, Period 3

D50 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, East Gaulish (Rheinzabern). A bowl in Ricken's Julius I or Lupus style, with ovolo (Ricken and Fischer 1963, E46). The ovolo (Ricken and Fischer 1963, E42) and acanthus (Ricken and Fischer 1963, P145) are on a stamped bowl of Julius I (Ricken 1948, Taf. 154, no. 3) and a stamped mould of Lupus (Ricken 1948, Taf. 157, 7), both from Rheinzabern. The panel divider, on which the acanthus is set upside down, is Ricken and Fischer's O273, which occurs on an unstamped bowl in the same general style (Ricken 1948, Taf. 161, no. 10). c. AD 200-250. Fill 11139, Pit 10910 (Group 676), Area N, Period 5

D51 Bowl f37, East Gaulish, in Ricken's Victor II-Januco style at Rheinzabern. The ovolo (Ricken and Fischer 1963, E43) is on a stamped mould of Victor (Ricken 1948, Taf. 233, no. 1). The mask (Ricken and Fischer 1963, M5) and pillar (Ricken and Fischer 1963, O231) are on a mould in the style of these potters. The rosette above the pillar is apparently an unrecorded motif. c. AD 200-260. Fill 6012, Post-hole 6011 (Group 475), Area H, Period 7

D52 Bowl f37, East Gaulish. A substantially complete bowl in the style of Afer iii of Trier. The ovolo (Fölzer 1913, Taf. xxxii, no. 954), dog (Gard 1937, no. 76) and medallion are on a signed mould from Trier. The Diana with hound (Fölzer 1913, Taf. xxix, no. 478) is on a stamped bowl from de Meern (Holland). c. AD 200-260. Fill 10337, Ditch 10404 (Group 838), Area F, Period 5

D53 Bowl f37, East Gaulish, with a mould-stamp of Iulius viii (Ricken and Fischer's Julius II) of Rheinzabern (see S45, below). The decoration includes the ovolo (Ricken and Fischer 1963, E23), and a pedestal-like motif (Ricken and Fischer 1963, O161?) in an arcade (Ricken and Fischer 1963, KB73). See Ricken (1948, Taf. 205, no. 9) for a similar decorative scheme. c. AD 225-250. Layer 6020 (Group 573), Area H, Period 5

D54 Bowl f37, East Gaulish, in Ricken and Fischer's Julius II-Julianus style (= Iulius viii-Iulianus iii) at Rheinzabern. The pillar (Ricken and Fischer 1963, O221), Venus (Ricken and Fischer 1963, M51, but without the mask) and Hercules (Ricken and Fischer 1963, M86) are all on a stamped mould of Iulius (Ricken 1948, Taf. 208, no. 22). c. AD 225-260. Layer 12041 (Group 966), Area R, Unphased

D55 (Not illustrated) Bowl f37, East Gaulish. A badly eroded bowl in the style of Dubitatus of Trier. The ovolo is Fölzer 1913, Taf. xxxii, no. 954. The decoration seems to consist of two animals alternating, a stag (probably Gard 1937, no. 58, but with both front legs complete) and a dog (Gard 1937, no. 84). c. AD 225-260. Fill 6171, Pit 6169 (Group 546), Area H, Period 4

Each entry gives: Potter (i, ii, where homonyms are involved), die, form, reading, published example (if any), pottery of origin, date, context information. Stamps on the decorated ware, above, or from key pottery groups, are discussed in detail.

Superscript (a), (b) and (c) indicate:

(a) A stamp attested at the pottery in question.

(b) Not attested at the pottery in question, but other stamps of the potter known from there.

(c) Assigned to the pottery on the evidence of fabric, distribution, etc.

Ligatured letters are underlined

S1 Acurio 5a Cup f33 ACVRIO·I (Walke 1965, Taf. 40, no. 51-2) Lezouxa. c. AD 150- 180. Fill 12009, Cremation Pit 12006 (Group 964), Area R, Period 3

S2 Advocisus 2a' Dish f79R or TgR [ADVO] ISI Lezouxa. c. AD 170-190. Cleaning layer 14637 (Group 8005), Area L

S3 Aestivus 2a Cup f33 [A]IISTI[V]I:M Lezouxb. c. AD 160-190. Fill 7126, Pit 7127 (Group 868), Area G, Period 4

S4 Aeternus 5a Dish f31 [AET]ERNII Lezouxa. c. AD 155-185. Layer 10188 (Group 8014), Area F, unphased

S5 Albucianus 6a Dish f31 ALBVCIANI Lezouxa. There are several examples of this stamp in a group of late Antonine samian recovered off Pudding Pan Rock, Kent. Otherwise, the only evidence of date is a single example on a dish f31R, from Catterick. However, the use of some of his other stamps on dishes f79 and f80 also points to a range c. AD 160-200. Fill 17037, Pit 17038 (Group 948), Area Q, Period 4

S6 Albucius ii 3b Cup f33 ΛLBVCIOF (Hartley and Dickinson 1981, 266, no. 2) Lezouxa. There is no particularly useful dating evidence for this stamp of Albucius ii, but from his record in general Antonine activity is not in doubt. His wares occur at forts both on Hadrian's Wall and in Antonine Scotland and his stamps are found on a range of forms including cup f27, and dishes f31R, f79 and f80. c. AD 50-180. Fill 7390, Pit 7389 (Group 867), Area G, Period 4

S7 Albucius ii 6b Cup f33 AL[BVCI] Lezouxa. This stamp is known in Antonine Scotland, from Balmuildy (Miller 1922, pl. xxxvii, no. 1), and an example in Chesters Museum almost certainly comes from one of the Hadrian's Wall forts. It was used on dish f42, which is unlikely to be later than c. AD 150, but also on dish Ludowici Tg, which suggests use of the die after AD 160. c. AD 150-180. Fill 4212, Pit 4211 (Group 756), Area K, Period 3

S8 Albucius ii 6b Dish f18/31R or f31R ALBVCI (Miller 1922, pl. xxxvii, no. 1) Lezouxa. c. AD 150-180. Cleaning layer 5602 (Group 8002), Area I

S9 Albucius ii 6c Cup f33 ALBVC[I] Lezouxa. c. AD 150-180. Layer 6053 (Group 506), Area H, Period 3

S10 Albucius ii 6h Bowl f37 ALBVCI (Stanfield and Simpson 1958, pl. 120, no. 1) Lezouxa. Decorated bowls with this mould-stamp occur on Hadrian's Wall and in Antonine Scotland. There is also one in the Wroxeter Gutter deposit. c. AD 150-180. Layer 7073 (Group 1319), Area G, unphased

S11 Arilira 1a Dish f31R [ΛRI] I Λ (Dickinson 1986, 187, no. 3.12) Triera. c. AD 180-260. Fill 4798, Pit 4913 (Group 4016), Area K, unphased

S12 Attius ii 6a Dish f18/31-31 [ΛTTI]V ·EF Lezouxb. c. AD 135-165. Fill 23123, Pit 23118 (Group 906), Area N, Period 3

S13 Banuus 3a Dish f31 BΛ VI·M Lezouxb. c. AD 175-200. Layer 16081 (Group 8001), unstratified, Area H

S14 Banvillus 2a Cup f33 BANVI[LLIM] (Miller 1922, pl. xxxvii, no. 2) Les Martres-de-Veyrea. c. AD 130-155. Layer 12150 (Group 4031), unstratified, Area R

S15 Bio 2b Cup f24 BIOFECIT (Hull 1958, fig. 99, no. 3) La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 50-70. Fill 7142, pit 7141 (Group 758), Area G, Period 2B

S16 Borillus i 10d Dish f18/31 BORI[L]LIM (Roosens 1976, Taf. 1) Lezouxa. Graffiti cut inside the base, after firing, FIR and VET. c. AD 145-165. Layer 6316 (Group 547), Area H, Period 4; Fill 6603, Ditch 6825 (Group 3007), Period 3

S17 Calvus i 5b Platter f15/17 or f18 [OFCA]LVI, in a frame with swallow-tail ends (Bechert and Vanderhoeven 1988, Taf. 40, no. 95) La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 70-90. Layer 13576 (Group 600), Area I, Period 3

S18 Calvus i 5m Platter f15/17 or f18 OFCALVI (Walke 1965, Taf. 40, no. 105a) La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 70-85. Layer 4899 (Group 749), Area K, Period 3

S19 Campanus ii 2a Dish f79 [C]AMPANIO (Simpson 1987, 158, no. 34) Lezouxa. c. AD 160-190. Fill 8009, Pit 9029 (Group 783), Area D, Period 3

S20 Celsus ii 1b Cup f27 [OFC]ELSI (Knorr 1921, Taf. IX, no. 46) La Graufesenqueab. c. AD 80-110. Fill 6541, Pit 6543 (Group 654), Area H, Period 3

S21 Celsus iii 2a Bowl f38 CELSI M (Dannell 1971, 303, no. 24) Lezouxa. c. AD 160- 190. Fill 6029, Pit 6030 (Group 553), Area H, Period 4

S22 Cerialis v 3a Bowl f37 CERI[ALIS] (Ludowici 1927, 240, c) Rheinzaberna. c. AD 160-190. Fill 11302, Pit 11303 (Group 671), Area N, Period 5

S23-4 Cinnamus ii 5b Bowl f37 (2) CI[NNAMI] retr., [CIN]NAMI retr. (Walke 1965, Taf. 39, no. 11) Lezouxa. Decorated bowls with this stamp occur frequently on Hadrian's Wall, but are even more common in Antonine Scotland. c. AD 150-180. Layer 4706, Area K, Period 3; Layer 10310 (Group 1312), Area F, unphased

S25 Cintussa 1a Dish f18/31R C·INT·VSSA Lezouxc. c. AD 130-160. Fill 9016, Pit 9015 (Group 783), Area D, Period 3

S26 Cintusmus i 5a Dish f31R CINTVS[M] (Dickinson 1990, fig. 183, no. 11) Lezouxa. c. AD 160-190. Fill 16083, Well 6280 (Group 531), Area H, Period 3

S27 Cobnertianus 1a Dish f18/31R-31R COBN[ERTIAN ] (Durand-Lefebvre 1963, 78, no. 238) Lezouxc. c. AD 155-165. Cleaning layer 5602 (Group 8002), Area I

S28 Cotto i 3a Dish COTTO[F] (Bémont 1976, no. 133) La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 45-65. Fill 13800, Pit 13809 (Group 397), Area J, Period 3

S29 Cracuna i 1a Cup f33 CRACVNA·F (Hartley 1972, fig. 81, no. 69) Lezouxa. c. AD 125-155. Fill 20286, Pit 20185 (Group 711), Area L, Period 4

S30 Crestio 5b' Bowl f29 OFCRESTI[O] (Durand-Lefebvre 1963, 82, no. 250) La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 50-65. Layer 6418 (Group 506), Area H, Period 3

S31 Crestus 1a Bowl f29 OFCRE TI retr. La Graufesenqueaa. Many instances of this stamp have been noted on sites founded in the early Flavian period, such as Rottweil, York and the Nijmegen fortress, and it is also known in Period IIA at Verulamium (Hartley 1972, fig. 81, no. 34). A single example of his work, a cup f24 with a different stamp, suggests some pre-Flavian activity. c. AD 65-85. Pit 21020 (Group 167), Area L, Period 2B

S32 Crestus 3a Platter f15/17 or f18 OΓ.[CRES] (Nash-Williams 1930, 173, no. 30) La Graufesenqueb. c. AD 70-85. Cleaning layer 5602 (Group 8002), Area I

S33-4 Divixtus i 9d Bowl f30 (2) [DIV]IX·F·, DIVI[ (Miller 1922, pl. xxxvii, no. 12). c. AD 150-180. Layers 6025 and 6118 (Group 573), Area H, Period 5

S35 Domitus i 1c Platter f15/17 or dish f18/31 DO[MITVSF]. Domitus i is known to have worked at both Les Martres-de-Veyre and, later, at Banassac. There is one example of this stamp from Banassac (Cavaroc 1964, no.30), but the fabric of the Heybridge dish and the heavy concentration of the stamp in Britain suggest that the die was also used at Les Martres. As several of his dies were used at both centres, this is not impossible. A dish in a London Second Fire deposit, from one of his other dies, was also made at Les Martres and, though unburnt, is almost the only evidence for the date of his activity there. c. AD 100-120. Fill 19150, Pit 19149 (Group 658), Area P, Period 3

S36 Donatus iii 1d Dish f31R [DONA]TVSF (Ludowici 1927, 214, c) Rheinzaberna. c. AD 80-240. Fill 5864, Pit 5805 (Group 444), Area J, Period 6

S37 Felix i 2d Bowl f29 [OFFEI]CIS La Graufesenqueb. This stamp comes from a die that was used almost exclusively on f29 bowls. Dating relies largely on the decoration of these bowls, but the stamp occurs in the Boudiccan burning at Colchester (Hull 1958, fig. 99, no. 5). c. AD 55-65. Fill 9370, Pit 9218 (Group 768), Area D, Period 3

S38 Gabrus ii 2a Dish f31 GABRVS·F· (Hull 1963, fig. 48, no. 16) Colchestera. The fabrics associated with this stamp, and its exclusively East Anglian distribution, suggest the die was used only at Colchester, though it is not impossible that this was the same Gabrus who worked at Trier and Lavoye. The forms stamped with Die 2a include dishes f18/31R, f31, f31R and f79/80, indicating activity mainly after c. AD 160. c. AD 160-190. Fill 7152, Pit 7118, Area G, Period 3; Fill 7202, Pit 7157 (Group 852), Area G, Period 3

S39 Gallio 1a Cup f33 Λ IO Lezouxc. c. AD 140-200. Fill 8038, Pit 8037 (Group 789), Area E, Period 3

S40 Gippus 2a Cup f33 IPPI·M (Dickinson 1986, 189, no. 3.58) Lezouxa. This stamp occurs in a group of samian from Tác (Hungary), almost certainly burnt in the Marcomannic Wars, and was also used on the mid-Antonine dish, f18/31R-31R. A range c. AD 155-185 is likely, therefore. Fill 7061, Pit 7060 (Group 310), Area G, Period 2B

S41 Gippus 2a Cup f33 IPPI·M (Dickinson 1986, 189, no. 3.58) Lezouxa. c. AD 155-185. Surface 10104 (Group 813), Area F, Period 4

S42 Gnatos/Gnatius 7a Cup f33 NΛTOS Lezouxc. c. AD 135-155. Cleaning layer 18737 (Group 8003), Area J

S43 Illixo 7a Bowl f38 ILLIXOF Lezouxa. c. AD 160-180. Fill 7390, Ditch 7389 (Group 867), Area G, Period 4

S44 Iulius Numidus 2a Cup f33 IVL·NVMIDI Lezouxb. c. AD 160-190. Ditch 5390 (Group 422), Area J, Period 4

S45 Iulius viii 3g Bowl f37 (mould stamp in the decoration) [I]VLIV[SE] retr. Rheinzaberna. There is no internal dating evidence for this particular stamp, but the potter's work occurs in a group of wasters from Rheinzabern dated (provisionally) broadly c. AD 210/220-260 (Reutti 1983, 54-60). A range c. AD 225-250 seems appropriate for this bowl. Layer 6020 (Group 573), Area H, Period 5

S46 Iustus ii 3b Cup f33 IVSTI·M Lezouxb. c. AD 160-190. Fill 10011, Pit 10012 (Group 811), Area E, Period 4

S47 Maceratus 2c Dish f31 MACERATI Lezouxa. c. AD 150-180. Fill 8167, Well 8188 (Group 788), Area E, Period 3

S48 Macrinus iii 5b Dish f31 MACRINI (Walke 1965, Taf. 42, no. 209) Lezouxa. c. AD 150-180. Fill 14634, Pit 14632 (Group 722), Area L, Period 6

S49 Magio i 1a Dish f31 ·[MΛGIONI·] (Dickinson 1986, 190, no. 3.85) Lezouxb. Only the stop in the ansate beginning to the frame of this stamp survives, but it is distinctive enough to make attribution certain. The stamp is known on dish f31R and on f31 dishes dated to the later 2nd century. It has been noted from Chesterholm and Chesters. c. AD 160-190. Fill 4430, Pit 4487 (Group 739), Area K, Period 4

S50 Marcellus iii 11a Dish f18/31 or f31 MΛRCELLIVS (ORL B33, Taf. 19, no. 82) Lezouxa. c. AD 130-155. Fill 9039, Pit 9038 (Group 806), Area D, Period 4

S51 Martialis ii 1b Dish f18/31-31 MA[R]TIALIS (Walke 1965, Taf. 42, no. 235) Lezouxb. c. AD 125-145. Cleaning layer 5619 (Group 8002), Area I

S52 Martinus iii 7a Dish f31 M·ΛRTI (Durand-Lefebvre 1963, 143, no. 437) Lezouxa. c. AD 160-190. Fill 8094, Well 8188 (Group 788), Area E, Period 3

S53 Masc(u)lus 19a Platter f15/17 MASCV[LVS] (Dannell 1971, 310, no. 64) La Graufesenquea. The bulk of Masc(u)lus's output is Neronian, and this stamp has been noted in Period II at Verulamium (c. AD 60-75) and in the Oberwinterthur Keramiklager, destroyed in the early AD 60s. However, as it also occurs several times in Flavian contexts, it is likely to have continued in use in the AD 70s. c. AD 60-80. Fill 15787, Pit 15757 (Group 900), Area M, Period 3

S54 Masc(u)lus 19a Platter f15/17 or f18 [MASCV]LVS La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 60-80. Fill 10376, Pit 10382 (Group 3068), Area F, Period 3

S55 Maternus iv 1a Dish f31R MΛTERNI Lezouxa. c. AD 160-180. Fill 5676, Post-hole 13181 (Group 648), Area I, Period 6

S56 Miccio vii 1a Cup f33 MICCIO[·F] (Hull 1963, fig. 48, no. 26). The die from which this stamp came was used at both Sinzig and Colchester. This piece is in Colchester fabric. c. AD 150-180. Layer 6053 (Group 506), Area H, Period 3

S57 Minuso ii 1a Cup f33 MINVSOF (Hull 1963, fig. 48, no. 28a). The die from which this stamp came was used at Colchester, and also at Trier, where it occurs on dishes f18/31, f31 and, perhaps, f31R. This piece is in Colchester fabric. As the potter stamped the f27 cup at Trier, he will certainly have worked there first, but as he also stamped f32 dishes there, he will scarcely have left Trier before the middle of the 2nd century. This could be an instance either of a potter migrating to another area or sending a workman there with some of his existing dies. c. AD 155-170. Fill 7390, Ditch 7389 (Group 867), Area G, Period 4

S58 Minutus 3b Flat dish MINVTVSF Trierb. c. AD 180-240. 4000, Unstratified, Area A1

S59 Muxtullus 1a Dish f31 ·MVXTVLLI·M (Walke 1965, Taf. 43, no. 264) Lezouxa. c. AD 160-180. Surface 6289 (Group 514), Area H, Period 3

S60 Muxtullus 1b Cup f33 [MV]XTVLLIM (Walke 1965, Taf. 43, no. 262) Lezouxb. c. AD 130-150. Layer 12093 (Group 970), Area R, unphased

S61 Niger ii 3b'' or 3b''' Platter f15/17 or f18 FN[GR<I> La Graufesenqueaa. The stamp is more likely to have come from Die 3b'', since no examples of 3b''' have been noted on dishes. c. AD 55-70. Fill 18225, Post-hole 18242 (Group 9003), Area J, unphased

S62 Paterclos/Paterclus ii 6a Dish f18/31 [PΛTERC]LIM (Dickinson 1986, 193, no. 3.135) Les Martres-de-Veyreb, c. This potter is known to have worked at both Les Martres and Lezoux. The dish is in one of the fabrics in the Les Martres range. c. AD 100-125. Fill 13884, Pit 13883 (Group 595), Area I, Period 3

S63 Paterclos/Paterclus ii 10a Dish f18/31 [PΛTE]RCLOSFE (Allgaier 1992, no. 78) Les Martres-de-Veyre. c. AD 100-110. Layer 11206 (Group 8007), unstratified, Area N

S64 Pentius 1a Dish f79 or Tg PIINTII·M[Λ ] Lezouxc. c. AD 160-190. Layer 6053 (Group 506), Area H, Period 3

S65 Pervincus 3f Bowl f37 PIIRVINCVS retr. (With N reversed) (Ludowici 1927, 243, d) Rheinzaberna. c. AD 200-240. Cleaning layer 5602 (Group 8002), Area I

S66 Perpetus 5c Dish or bowl PERPETVS (Ludowici 1927, 226, e). The die for this stamp is known to have been used at Rheinzabern, like many of his others. However, the decoration of the bowl and the fabric both suggest origin at Trier. c. AD 180-240. Fill 15353, Pit 15354 (Group 701), Area M, Period 6; Fill 15355, Pit 15356 (Group 701), Area M, Period 6

S67 Pistillus 4a Cup f33 PISTILLII Lezouxa. Apart from single examples of dishes f79/80 and f80, all the stamps recorded from this die are on f33 cups. There are nine cups in the Wroxeter Gutter deposit and one from Haltonchesters. This is the only example to show double I at the end of the stamp, the rest reading PISTILLI. The intrusive (fainter) stroke is presumably due to a scratch on the die. c. AD 160-190. Fill 4579, Pit 4526 (Group 729), Area K, Period 3

S68 Pont(i)us 8h Cup f27g O ONTI (Dickinson 1986, 193, no. 3.154) La Graufesenqueaa. Most of Pont(i)us's output is Flavian, with stamps from other dies occurring at sites such as Cappuck, Inchtuthil and the Saalburg. This stamp occurs mainly on f27 cups, but a few examples on cup f24 suggest that the die was in use in the late Neronian period. c. AD 65-90. Fill 5146, Pit 5147 (Group 409), Area J, Period 3

S69 Pridianus 7a Dish f18/31R or f31R PRIDFEC La Madeleineb. c. AD 130-160. Layer 4706 (Group 905), Area K, Period 3

S70 Priscinus 4b Dish f31 PRISC.../SF Lezouxb. c. AD 150-170. 15000 (Group 8006), unstratified, Area M

S71-2 Reburrus ii 3a Cup f33, Dish f31 REBVRRI·OFF, REBV[R]RI·OFF (Dickinson 1996, fig. 143, no. 74) Lezouxa. c. AD 145-170. 3830, unstratified, Trial Trench 5; 4000, unstratified, Area A1

S73-4 Reginus ii 1a Dish f18/31R, Cup f33 [REGI]NI·M, REGI[N]I·M (Hartley 1961, 107, no. 7) Les Martres-de-Veyreb. c. AD 115-145. 3999, unstratified, Area X; Cleaning layer 5610 (Group 8002), Area I

S75 Roppus ii 1a Dish f18/31 RO[PPVSFE] (Hartley 1970, 26, no. 56) Les Martres-de-Veyreb. c. AD 115-135. Fill 23019, Pit 23012 (Group 694), Area N, Period 4

S76 Rottalus 1a Dish f31R [RO]TTΛLIM (Dickinson 1986, 194, no. 3.176) Lezouxa. Recorded from Benwell, Chesters and the Brougham cemetery, where most of the Lezoux samian is late 2nd century, and on dishes f79, f79R, f80 and Ludowici Tg, this stamp clearly falls within the period c. AD 160-200. Fill 8802, Pit 8801, Area P, Period 6

S77 Ruffus ii 2a Dish 18/31 RVFFI·M (Curle 1911, 240, no. 82) Lezouxa. c. AD 125-145. Fill 12215, Cremation pit 12219 (Group 964), Area R, Period 3

S78 Rufinus iii 4c or 4c' Cup f27g [OF]RVFI[N] or [ F]RVFI[ ] (Durand-Lefebvre 1963, 204, no. 634) La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 65-85. Fill 7623, Ditch 25045 (Group 5), Area G, Period 2A

S79 Rufus iii 3b Platter f18 [OFRV]FI (Ribeiro 1959, VI, no. 55) La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 70-90. Layer 5693 (Group 609), Area I, Period 3

S80 Sacerus ii Uncertain 1 Dish f31 SΛCERIKI Lezouxc. c. AD 170-200. Fill 4844, Pit 4913 (Group 4016), Area K, Period 4

S81 Severinus iii 3a Dish f32 SIIVIIRINVS (Ludowici 1927, 230, c) Rheinzaberna. c. AD 180-240. Cleaning layer 5602 (Group 8002), Area I

S82 Sextus v 4c Dish f31 [SEXT]I·MA Lezouxb. c. AD 160-200. Cleaning layer 5602 (Group 8002), Area I

S83 Sulpicius 3a Platter f18 OFSVIPIC La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 80-110. Layer 5693 (Group 609), Area I, Period 3

S84 Sulpicius 8j Cup f27 SVLPICI La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 80-110. Fill 24198, Pit 24197 (Group 696), Area M, Period 4

S85 Tarvillus 1b Cup f33 (complete) TΛRVILLIM Lezouxc. c. AD 135-150. Fill 12200, Cremation pit 12203 (Group 964), Area R, Period 3

S86 Tasgillus ii 4b Cup f27 TASCI IV retr. (Terrisse 1968, pl. liv, second example). The die for this stamp was used at both Les Martres-de-Veyre and Lezoux. This pot was made at Les Martres. c. AD 110-125. 17000 (Group 8024), unstratified, Area A4

S87 Tauricus i 1a Cup f33 TAVRICIOF Lezouxb. c. AD 150-180. 4001 (Group 8021), unstratified, Area A1

S88 Verus vi 2c Dish f31R ]/ERVSFEC, in guide-lines (Ludowici 1927, 232, b). The die for this stamp was used at both Rheinzabern and Trier. This piece comes from Rheinzabern. c. AD 180-240. Cleaning layer 5427 (Group 8002), Area I

S89 Virio-- 1a Platter f15/17 VIRIO La Graufesenquec. c. AD 55-75. Fill 4842, Pit 4843 (Group 1147), Area K, unphased

S90 Virthus 2a Dish R VIRTHVSFEC+ La Graufesenqueaa. c. AD 50-70. Cleaning layer 5611 (Group 8002), Area I

S91 Virthus 3a' Cup f27 <VI>RTHVS[FE<C>] La Graufesenqueb. c. AD 60-75. Layer 6420 (Group 509), Area H, Period 4

S92 Vitalis iii 2a Platter f15/17 or dish f18/31 [V]+A[LISM·S·F (Hartley 1972, 233, S8) Les Martres-de-Veyrea. c. AD 100-120. Layer 6316 (Group 547), Area H, Period 4

S93 ]CIS? on Platter f15/17 or f18, South Gaulish. Neronian. Fill 407, Pit 410, Area W, Period 3

S94 ]VC? on Cup f27g, South Gaulish. Neronian. Cleaning layer 14573 (Group 8005), Area L

S95 MS[ on Platter f15/17 or f18, South Gaulish. Neronian. Fill 10609, Post-hole 10745 (Group 822), Area F, Period 4

S96 ]I or I[ on Platter f15/17R or f18R, South Gaulish. Neronian or early-Flavian. Fill 13639, Pit 13640 (Group 594), Area I, Period 3

S97 ..OF..NI..on Cup f27, South Gaulish. Neronian or early-Flavian. Fill 8537, Pit 8524 (Group 656), Area P, Period 3

S98 III[ or ]III on Cup f27g, South Gaulish. Neronian or early-Flavian. Fill 20117, Pit 20116 (Group 2042), Area L, Period 2B

S99 OFPO[? on Bowl f29, South Gaulish. c. AD 70-85. Cleaning layer 5597 (Group 8002), Area I

S100 V·IIN or V·IIV on Platter f18, South Gaulish. Flavian. Layer 5149 (Group 3024), Area J, Period 3

S101 ]/I on Platter f18, South Gaulish. Flavian. Fill 20180, Pit 20174 (Group 707), Area L, Period 3

S102 VN[ on Cup, South Gaulish. Flavian or Flavian-Trajanic. Layer 5693 (Group 609), Area I, Period 3

S103 IIIV...VN retr. on Dish f18/31 (complete), Central Gaulish. Hadrianic. Fill 12199, Cremation pit 12203 (Group 964), Area R, Period 3

S104 CN[ retr. (?), mould-stamp in the decoration, Central Gaulish. Hadrianic or Antonine. Fill 8737, Pit 8736 (Group 902), Area P, Period 6

S105 SI[ or SE[ on Dish f31, Central Gaulish (Les Martres-de-Veyre). Hadrianic-Antonine. Fill 3587, Cremation Pit 3585 (Group 317), Area W, Period 2B

S106 ]I I\/ on Dish f31, Central Gaulish. Early to mid-Antonine. Cleaning layer 5610 (Group 8002), Area I

S107 GI[ on Cup f33, Central Gaulish. Early to mid-Antonine. Fill 10182, Ditch 25245 (Group 361), Area G, Period 3

S108 IXX[ or ]XXI on Dish f18/31R or f31R, Central Gaulish. Antonine. Fill 5537, Post-hole 5538 (Group 395), Area J, Period 3

S109 IVL[ on Dish f31, Central Gaulish. Antonine. Layer 6226 (Group 573), Area H, Period 5

S110 ]NI·M on Dish f31, Central Gaulish. Antonine. Layer 6227 (Group 573), Area H, Period 5

S111 ]IM or IMΛ on Dish f31, Central Gaulish. Antonine. Layer 10289 (Group 820), Area F, Period 4

S112 SE[ on Dish f31, Central Gaulish. Antonine. Fill 16148, Pit 16149 (Group 559), Area H, Period 4

S113 MAC[ on Cup f33, Central Gaulish. Antonine. Fill 10182, Ditch 25245 (Group 361), Area G, Period 3

S114 Perhaps TITVLI[ or TITVLL[ on Cup f33, Central Gaulish. Antonine. Layer 16187 (Group 573), Area H, Period 5

S115 SAT[ on Dish f31, Central Gaulish. Slightly burnt. Mid- to late Antonine. Fill 8094, Well 8188 (Group 788), Area E, Period 3

S116 Possibly ]ENIL.. \TI on Dish f31 or f31R, Central Gaulish. Mid- to late Antonine. Fill 5800, Well 5806 (Group 639), Area I, Period 4

S117 ΛT....M on Dish f31R, Central Gaulish. Mid- to late Antonine. Surface 7549 (Group 862), Area G, Period 4

S118 C[, O[ or ]O on Dish f31R, Central Gaulish. Mid- to late Antonine. Layer 15035 (Group 8006), Area M, unphased

S119 ]ΛPV [ (?) on Dish with concave base, East Gaulish (Rheinzabern). Late 2nd or first half of 3rd century. Fill 15073, Pit 15005 (Group 701), Area M, Period 6

S120 ]MITIV[? on Dish f32, East Gaulish (Rheinzabern). Perhaps a stamp of Primitius, but the reading is not certain. First half of 3rd century. Fill 4994, Pit 4989 (Group 1147), Area K, unphased

S121 SE[ (S reversed) on Cup f27, Central Gaulish. Hadrianic or early Antonine. Inscribed in the centre of the base before firing, instead of a potter's stamp. Fill 5157, Pit 5158 (Group 409), Area P, Period 3

S122 ]an[ retr. on bowl f37, Central Gaulish. The signature was inscribed upside down below the decoration, before the mould was fired. This could in theory belong to either Quintilianus i or Ianuaris i, whose styles of decoration are sometimes indistinguishable, and who are both known to have used signed moulds. However, the lettering makes attribution to Ianuaris almost certain. c. AD 125-150. Layer 24058 (Group 8006), Area M, unphased

S124 Tetturo... retr. on bowl f37, from a mould inscribed upside down below, the decoration, before firing. Signed bowls of Tetturo are known from Toulon-sur-Allier and Rogers (1999, 254) believed that he only worked there. However, much of his known output is in Britain, and it is likely that he also worked at Lezoux at some stage in his career. The fabric of the Heybridge piece is rather redder than normal for Lezoux, but that is insufficient evidence to attribute it to Toulon. The provenance must remain doubtful, therefore. Bowls in his distinctive style from Alcester (in a pit filled by c. AD 160), Camelon, Corbridge and Inveresk suggest a range c. AD 30-160. Fill 20020, Pit 20019 (Group 711), Area L, Period 4

Cite this as: Willis, S. 2015, An analysis of some aspects of the samian pottery, in M. Atkinson and S.J. Preston Heybridge: A Late Iron Age and Roman Settlement, Excavations at Elms Farm 1993-5, Internet Archaeology 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.1.willis

Brenda Dickinson's report provides a substantive guide to the samian pottery recovered, identifying major trends and including a comprehensive catalogue. Her work enables some further aspects of the use and consumption of samian to be considered and compared with wider patterns discernible in Roman Britain.

Samian is, of course, a particularly useful artefact class for the archaeologist given: (i) its standardisation of form and fabric, (ii) its sequential typological development, change in decorative detail and stamps, that are well understood and facilitate relatively close dating, and (iii) its wide distribution and reporting, which enable comparative analysis. Various studies have demonstrated that samian was particularly valued or prized among contemporary communities. Distinctive and unusual in appearance compared to other contemporary pottery types, samian is perceived, by archaeologists, to have been a high-status commodity. Certainly across Britain, samian was in the vanguard of imports arriving at indigenous sites in the years following the conquest and circulated in a manner different from other pottery types (cf. Willis 1997a; 1998); some samian assemblages even appear to represent 'diplomatic' gifts (Haselgrove et al. in press).

Evans' study of graffiti on Roman pottery (Evans 1987) has shown that samian was much more frequently inscribed with names and marks than other pottery types, with marking evidently expressing a concern to denote ownership (see this publication for an alternative interpretation of X-graffiti ). Further, studies of the repair of broken pottery vessels via lead riveting or cleats shows that samian was repaired with disproportionate frequency compared to other types of vessels (Marsh 1981, 227; King and Millett 1993, table 16.5; Evans 1996a, 89; Evans 1996b, 62; Booth 1997, 123). In other words, a broken samian vessel was more likely to be repaired than any other type of pot, and this is a widespread pattern, identifiable at all types of site. The large majority of decorated samian vessels are bowls and it seems that these vessels may have been particularly valued, either because they were relatively expensive (reflecting the amount of labour taken to produce them, plus transport costs) or perhaps because the form and finish were attractive for use as (communal?) drinking vessels. Overall scrutiny of the incidence of samian seems to confirm that it was, indeed, a status symbol, relating to wealth, social and cultural identity (Willis 1998). Samian, therefore, can be a sensitive indicator of a range of processes to a degree that is not possible with other pottery types of the period. For these reasons it is potentially useful to explore further the character of the samian assemblage recovered, with the advantage of such a large sample of this pottery having been recovered.

Recent studies have shown consistent differences in the pattern of samian occurrence that seems to reflect site type strongly. Major towns and sites associated with the Roman military show a pattern of more frequent samian use and deposition, while at others (small towns, roadside settlements, religious foci and rural sites) samian is much less frequent relative to other pottery types. Variations in the frequency of samian at different settlement types appear to have been socially structured. Differences in access to quantities of samian may have had an economic basis (i.e. it may not have been easily affordable), and/or particular cultural attitudes may have been influential (e.g. at some types of site samian may have been considered an important regular mechanism of status display among certain social groups, and a symbol of 'Romantitas' and wealth, while at others, people may not have used sets of samian as a regular everyday status symbol, but less often, for specific purposes or events). Comparison of the samian assemblage from Elms Farm with patterns recently identified for other sites in Britain is potentially instructive.

In order to establish the nature of samian use and consumption at Heybridge, several approaches have been adopted. A useful index of the general pattern of samian use and consumption can be established by quantifying its occurrence within a series of phased pottery groups. As noted elsewhere, the key groups are considered to be both representative of the pottery being consumed at the site through various phases and 'good groups' from a methodological point of view. The data from these groups have been supplemented here using those from the 'wider pool', that is, further good, representative and stratified groups, which are also used elsewhere in the analysis of the pottery assemblage. Combining the quantitative information from these groups by phase results in unusually large samples, which should provide a reliable guide to the overall frequency of samian consumption through time. Data on the occurrence of samian within these groups are presented in Tables 14 and 15. The data are derived only from groups in which samian sherds are present (which is a function of the data available to this author), and exclude, also, groups that appear to include structured special deposits, or, in one or two cases, some intrusive sherds. In effect, these criteria omit only a few of the key and wider pool groups (omissions from the key groups comprise the following: Ceramic Phase 4; KPG17 (20008), which appears to represent a structured element, and KPG15 (9214), which included no samian: Ceramic Phase 7; KPG26 (6280) which also seems to represent a structured element, and KPG27 (1589), which included no samian). That a small number of groups with no samian have been excluded from the analysis means, of course, that any figures indicating the percentage of samian pottery within phases slightly over-represents the actual frequency of this ware per phase vis-à-vis other pottery wares.

Table 14 shows the frequency of samian among pottery groups by phase when EVE is the measure; Table 15 shows the equivalent data where weight is the measure. Weight proportions are a good measure when the intention is to compare the composition of groups over time, between sites, etc., while EVE is also suitable for this purpose, it gives an impression of vessel turnover (cf. Orton 1989). Orton (1989) has recommended that both these measures be employed where possible. For reasons discussed below, one should not anticipate that these two measures will yield like results in terms of percentage figures etc. though they should, significantly, show similar trends. The data reproduced in Tables 14 and 15 show that despite the fact that, in absolute terms, a very large sample of samian was collected during fieldwork, it forms only 2.2% by weight of the pottery being deposited. It is noteworthy that although the quantities of samian within these groups are invariably modest, it is rarely absent from sizeable groups.

Considering, firstly, Table 14, a general pattern of low percentages is consistent through time and presumably reflects a comparatively low frequency of use of samian ware. Samian is present in Ceramic Phase 3 but forms only a tiny fraction of the pottery of that phase; this is not surprising since, away from Roman military sites and major aggregated centres, samian is generally only occasionally found among contexts dating to the mid-1st century AD (cf. Willis 1997a). The samian percentages for Ceramic Phases 4 and 5 are remarkably similar to each other and imply continuity in the consumption and deposition of samian through the early Roman period. These data are likely to be a reliable index, given the robustness of the sample (for these are large samples and combine data from six and nine good groups respectively).

| Ceramic phase and date range; component groups | Total EVE of pottery | Total EVE of samian | Samian as a % (by EVE) within CP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramic Phase 3, c. AD 20-55 | |||