Cite this as: Root, C., Kay, J.E., Kreike-Martin, N., Weng, C., Madsen, H. and Pare, R. 2024 The Agency of Civilians, Women, and Britons in the Public Votive Epigraphy of Roman Britain, Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.17

As the Roman Empire invaded and conquered different territories, its army and administrative apparatus brought changes to the experiences of the people already living in those territories. People brought under imperial rule either actively accepted or were forcibly assimilated into a Roman cultural complex of behaviours, social structures and material culture (Mattingly 2006, 17; Millett 1990, 83). 'Roman' culture, however, manifested itself across the island of Britain in widely varying manners in different territories at different times. Some individuals and communities quickly adopted Roman practices, while others were either selective or wholly averse to materially traceable 'Romanised' lifestyles (Millett 1990; Gardner 2013; Versluys 2014).

Cultural and institutional practices introduced to Britain via the Roman army and civilian administration included a new, widely variable pantheon of deities, some of which were sponsored by the state (Irby-Massie 1999; Fishwick 1961a; 1961b). The administration also introduced the technology of epigraphy (Ostler 2008, 138-143; MacMullen 1982; Mann 1985), and in particular, Latin religious epigraphy—a practice using a new written language for inscribing messages and dedications to the gods (Tomlin 2002; Haensch 2007; Pearce 2023). Before this introduction, written text was limited to a small number of the latest phase of Iron Age coinages of southern Britain (Creighton 2000), and there was neither a widespread practice of literacy or a written culture, nor a tradition of epigraphic inscription. After conquest, there is little evidence in Britain for the widespread acceptance of Latin literacy, even though it was a part of the military and administrative structure (Tomlin 2018a; Raybauld 1999; Williams 2007; Hope 2014; Birley 1986). Literacy, for example, was particularly uncommon for women in the Roman world (Hübner 2018), even though a basic literacy in public epigraphy may have been more widespread (Woolf 1996; Bodel 2010).

The new, public, religious inscriptions on stone in Roman Britain, however, did not only commemorate Roman deities. It also recorded the names of local deities whose worship preceded the conquest, either through the specific mention of their individual name or through a practice called interpretatio (Tacitus, Germania, 43). Epigraphic interpretatio is one of the most important sources of written historical evidence about the names and functions of pre-Roman deities in Britain (Webster 1995; Ando 2008, 43-58; Goldberg 2009; Zoll 2014). The process translated individual deities from two different cultural groups in order to make the deities mutually intelligible in cross-cultural exchange (Woolf 2013). For example, the Roman 'Mars' and the British 'Belatucadrus' were combined to become 'Mars Belatucadrus'. In this article, we have used modern, standardised versions of the names of pre-Roman deities such as Belatucadrus or Veteris, whose names could be spelled in a variety of ways. These new hybrid deities took on characteristics of both of the deities in their name. Through interpretatio Romana, 'Belatucadrus' became translated as an aspect of Mars spatially and culturally tied to Britain, perhaps with his own specifically local practices and attributes, and through interpretatio Celtica, 'Mars' became translated as a close Roman equivalent of the native British deity (Ando 2005; Zoll 1995b). The specificity of dedications in Roman religious practices allowed phrasing to serve as a marker of cultural assimilation (Haensch 2007, 180). It was a means not only for making the local religion more interpretable and accessible to Romans, but also to encourage unity between newly conquered provinces and Rome and to encourage indigenous people to worship Roman deities (Ando 2008; Webster 1995).

The current scholarly understanding of public religious epigraphy in Roman Britain is that the army was the driving force behind its spread and implementation (Irby-Massie 1999; Zoll 2014; Biró 1975). This is true on both a technological level, because public worship of deities in Latin epigraphy was brought in with the Roman military conquest of Britain, but also at the level of individual and group agency, as soldiers most commonly used this new technology to spread the worship of new gods among the communities they encountered (Tomlin 2018b, 195). These soldiers did not all originate from Rome itself. As the Roman Empire expanded, men from newly conquered provinces were incorporated into the Roman army, which was composed of a diverse range of people from a wide array of places (James 1999). Hadrian's Wall, in particular, is understood as the centre of the surviving corpus of public religious epigraphy. The Wall was a physical stone boundary, and the political context of its construction indicates that while it was originally intended to divide communities—physically marking where the furthest reaches of the Roman world gave way to unconquered barbarian territory (Moorhead and Stuttard 2016, 123-7; Jackson 2020, 149)—it was much more a place of convergence and meeting than division (Collins 2007, 57).

Existing scholarship has used epigraphic evidence to examine how soldiers from across the Roman Empire, both local and non-local, created dedications to different deities in Britain (Irby-Massie 1996; 1999; Birley 1986; Tomlin 2018b). This type of analysis relies on either the etymological interpretation of individual names (which has its methodological issues), or uses the military history of cohorts and legions to delineate the geographical origins of the soldiers. This is largely in an effort to explore how and where non-local deities were imported to the island (Zoll 1995a; 1995b), as well as how different social ranks and military communities engaged with different gods (Biró 1975). But the current scholarly approach to interrogating patterns in religious epigraphy leaves a few questions to be answered. Because we rely on the technological (Biró 1975, 33-34; Mann 1985), linguistic (Mullen 2010; Aldhouse-Green and Raybauld 1999), and conquest (Webster 1995; Irby-Massie 1999) angles of the public epigraphic 'habit' or 'consciousness', we miss the opportunity to examine and compare how this new technology of worship was used by the people that we might not expect, especially as new data become available (Pearce 2024). If the wealth of literature on the 'Romanization' paradigm and its alternates (resistance, discrepant identities, creolisation, globalisation, etc.) has taught us anything, it is that we can find agency where we least expect it, and examining subordinate or minority perspectives enriches our understanding of how people lived and worked and worshipped in Roman Britain.

What, for instance, was the specific role of civilians in public religious epigraphy? Despite considerable scholarship on the military perspective, very little has been said about the agency of non-soldiers in this medium. The seminal paper on public religious epigraphy in Roman Britain by M. Biró (1975), for example, examined the contributions of civilians in certain civic and political categories and in dedications to particular gods and goddesses, but not in relation to the entire corpus of public religious epigraphy. More recent scholarship (Zoll 1995b; Irby-Massie 1999) has examined the social standing of the dedicators in relation to the deity invoked. While the majority of such inscriptions were certainly dedicated through military agency, there are still plenty of inscriptions by people who were not directly part of the military complex. Civilian epigraphy, of course, represents that small portion of society for whom the cost of commissioning such an inscription was economically viable, and focusing on religious epigraphy does not give an overall representative view of popular worship practices in the Roman world (Radman-Livaja 2021). When civilian religion is studied from epigraphic sources for Roman Britain and the empire, however, it is usually focused either on private or family practice, such as the records from the Vindolanda tablets (Bowman 1998) and tombstones (Salway 1965; Hope 1997; Saller and Shaw 1984), or in relation to soldiers in specific case studies, without exploring civilian agency as a whole (Tomlin 2018b). Other scholarship has looked at civilian participation in religious practices in certain regions (Green 1976), or from a non-epigraphic perspective, especially small finds (Henig 1984). But to the best knowledge of the authors, this has not been directly interrogated using the entire public epigraphic corpus available.

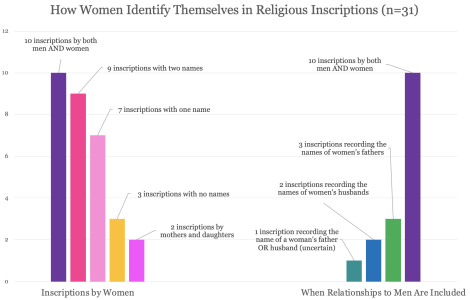

Similarly, and as a subset of civilian agency, what was the role of women in this new technology of worship? Women were responsible for roughly 10% of all inscriptions in Roman Britain (Allason-Jones 2005, Appendix 1), but the subject of their involvement in the creation of public religious epigraphy has remained largely untouched. A few notable exceptions include Audrey Ferlut's (2022) case study of the Westerwood altar to the Silvanae and Quadruviae, as well as Charlotte Bell's (2020) work on certain social classes of women and their appearance in the epigraphic record. But as with the agency of civilians in public dedication to the gods in Britain during the Roman period, there has been no systematic study of the agency of women across a large dataset of public religious epigraphy.

Most of the crucial large-scale data scholarship on public religious epigraphy focuses on reconstructing the religious pantheon worshipped in Roman Britain (e.g. Birley 1986), rather than on who is actually making the dedication. For example, important work by Amy Zoll has focused on understanding the nature and distribution of these pre-Roman gods through the cross-cultural syncretism inherent in the interpretatio process, especially at Hadrian's Wall (Zoll 1995a; 1995b). The process preserved to history the Latinised names of many local pre-Roman deities in Britain. It also, however, obscured the contemporary understanding of powers and the basic nature of those local pre-Roman deities because it was fairly reductive. Rome's religion(s) included hundreds of gods whose realms of power were 'hyper-specialized' (Ando 2010, 56), but only a small handful of Roman gods were used in the process of interpretatio, leaving multiple local deities to share names with a single Roman deity (Webster 1995). There may also have been a fundamental dissonance that complicated syncretism between local and imported gods. If local deities in Britain and north-western Europe were understood as spirits of place, genii loci, rather than anthropomorphised deities with specific realms of godhood (e.g. war, weather), then it would be difficult to syncretise or translate the identities of all of the deities invoked. Thus, the intricacies of local deities' identities and powers are concealed behind a handful of familiar Roman gods' names.

It also cannot be assumed that a previously non-literary religion was represented accurately in the new epigraphic tradition (Aldhouse-Green 2018, 7-9). Recent critiques of scholarly approaches to the concept of syncretism (e.g. Goldberg 2009) have argued that the process sets up a false dichotomy of 'Roman' vs 'native', and then seeks to investigate the messy space in between based upon our own modern expectations of cross-cultural exchange rather than according to how people living in Roman Britain might have understood their own religious beliefs. Eleri Cousins' recent (2020) book on Roman Bath, especially, challenges us to rethink what we think we 'know' and take for granted about Roman religion in Britain. Despite these caveats, however, we can make educated guesses about what such an act of translation meant to the native or newly arrived people, and use these inscriptions to piece together a picture of Latin-literate religious agency.

One way to re-evaluate how religious syncretism and cross-cultural exchange occurred on the ground in Roman Britain is to look more carefully at how specific types of agency functioned. In this article, we explore what religious epigraphy reveals about how people living in Britain under Roman rule participated in the creation of inscriptions to native, imported, or syncretised gods. By examining the geographical distribution, textual contents, and votive contexts of the public religious inscriptions surviving from Roman Britain, we interrogate who was responsible for commissioning inscriptions to different deities, according to the gender, occupation, and ethnic or tribal identities or geographic origins of those commissioners as recorded in the text. If we investigate how civilians, women, and locals participate in public religious epigraphy (in both syncretic and non-syncretic contexts), we learn more about how it actually spread, on the ground. If the army was responsible for dedicating to Roman deities, as previous scholarship (Irby-Massie 1999) has shown, was the reverse situation true? Were locals and/or civilians responsible for dedications to local deities?

We are particularly interested in finding out who was responsible for dedications to Roman/imported or native/local deities, especially when these are combined in a number of contexts. This is important because most of our surviving evidence is inherently Romanised, and very little of pre-Roman religious practices in Britain remains—especially not in written form. It is difficult to see how native deities were understood in their local context, because many of them only survive in syncretic contexts, and not on their own. When local gods were incorporated into this epigraphic practice of translation, how was that accomplished? Did different groups think different deities were important to translate? We could also consider the act of committing dedications to stone as itself an inherently syncretic practice in Roman Britain, making the explicit merging of religions in Latin epigraphy a syncretic act in both form and content. In this article, we examine how different types of pairings of deities from different cultures in public religious epigraphy happened, and whose agency was behind it. These pairings were intentional, with an intended audience: someone chose to pair Mars with Belatucadrus, or to include both the Numen Augusti and a local goddess in the same votive inscription. This article examines that intentionality more closely. Doing so lets us reconstruct patterns of cross-cultural exchange and connection. We might learn nothing new, but we might also find something exciting. An important clarification, however, is that we are not necessarily trying to tease out anything different about the nature of the deities. This cannot be discerned from these (often brief) stone inscriptions, and attempting such would be speculative at best.

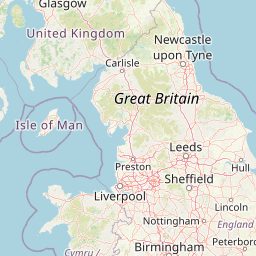

In the first section of this article, we study how soldiers and civilians, men and women, non-locals and locals all created dedications to gods from different religious cultural traditions, in order to identify broader patterns in agency. We compare the epigraphic commemoration of deities imported from the Mediterranean with that of gods who were likely local to Britain and nearby areas of north-western Europe. We find that different regions of the island produce a varying amount of evidence for different types of inscription. The prevalence of public religious epigraphy at Hadrian's Wall is already well known. We also find (following Zoll 2014 and others) that in the Midlands (e.g. Allason-Jones 2023), there are very few religious inscriptions at all, especially inscriptions to local deities or inscriptions with syncretism. This supports the interpretation of regional variance in the acceptance of Roman technology in Britain.

Notably, we find that people who omitted details about their occupations comprised over two-thirds of inscriptions to local, British, and north-western European deities. The stones upon which these inscriptions were made may have been too small to fit such information but, alternatively, people may have chosen to omit military affiliations or occupations intentionally. When dedicators' occupations were discernible, we find that Roman soldiers created many more inscriptions to local, British, and north-western European deities than civilians did—this is true in both syncretic and non-syncretic contexts. The analysis that follows therefore confirms the current scholarly understanding that it was soldiers who held primary agency in the religious epigraphic tradition in Britain.

Women were particularly unlikely to dedicate public religious epigraphy, and were explicitly mentioned in roughly four per cent of all inscriptions studied here. Civilians created a slightly higher proportion of religious epigraphy of all types; however, they accounted for less than ten per cent of inscriptions in each of the four main cultural categories we examine. Lastly, there were very few inscriptions explicitly made by Britons, whether found in their region of origin or elsewhere on the island. Most local people who contributed to the religious epigraphic corpus did so in groups, rather than leaving their individual names.

In the second section of this article we consider three possible ways in which the cross-cultural exchange of deities happened. We examine not only how people melded deities from the Mediterranean, Britain, and the North-western Provinces into double-named syncretic entities, through the process of interpretatio, but also how deities from different cultural traditions were included in the same inscription—both inscriptions in which individual deities from different cultural traditions appear together (yet as separate deities), and inscriptions in which individual and double-named deities were combined in a single dedication.

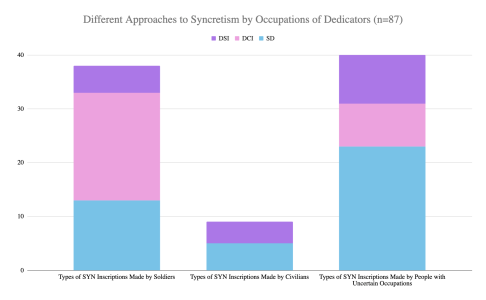

When people created inscriptions involving syncretism, they were unlikely to include details about their occupation. When they did include this information, however, it is clear that the vast majority of these dedicators were soldiers, across all three subcategories of syncretism. People with uncertain occupations created the majority of inscriptions that made use of interpretatio, fusing the names of the deities to create hybridised gods, while soldiers were more likely to maintain a separation between the identities of deities from disparate cultures. Civilians, on the other hand, never maintained this separation, choosing to employ interpretatio rather than to dedicate to two separate deities from different cultural traditions on the same inscription. Most inscriptions with syncretism (especially by soldiers) were found in the area around Hadrian's Wall, reaffirming the view that the Wall acted as a space of cross-cultural communication. Civilians (including women), however, did not create any syncretic inscriptions in the region of Hadrian's Wall, complicating this interpretation.

People living in Roman Britain engaged in the tradition of public religious epigraphy in varying ways, depending on the gender, occupation, and explicit origins of the dedicators. The militarised area around Hadrian's Wall was crucial not only to the process of religious syncretism, but also to the spread of Mediterranean cults (including non-Greco-Roman cults such as that of Mithras [e.g. RIB 1544]), by Roman soldiers and by civilians. The Wall was also the focus of inscriptions by people who included information about their origins, inscriptions by men, and inscriptions to local or indigenous deities by soldiers. Romano-British people living near Hadrian's Wall (especially soldiers) felt a greater need to create religious epigraphy (especially to local and syncretic gods) than anywhere else on the island. We interpret this as evidence to support the conclusion that Hadrian's Wall was an area where the distinctions between Roman and barbarian, soldier and civilian, may have been subtle. Otherwise, religious epigraphic traditions in Roman Britain were regionally idiosyncratic and different sites show varying degrees of the adoption of the practice. Inscriptions by civilians, by women, and by locals did not necessarily follow the same paradigms as inscriptions by soldiers. Civilians were slightly more likely than soldiers to create dedications to indigenous deities and inscriptions with syncretism in the south of the island.

In order to investigate who played a role in public epigraphic dedications, we catalogued the data from the Roman Inscriptions of Britain Online (RIB) database (Vanderbilt 2022). RIB was originally contained within three Volumes, of which Volumes I (Collingwood and Wright 1965) and III (Tomlin et al. 2009) were digitised into the online database by the time of this study. Volume I contains 2401 monumental inscriptions from Britain found prior to 1955. Volume III contains 550 monumental inscriptions from Britain found between 1995 and 2006. Volumes I and III therefore contain a total of 2951 Romano-British monumental inscriptions recovered and digitised before 2006. The online database also includes all corrigenda, as well as inscriptions published in Britannia up to 2006, and is the most complete dataset of the RIB (we have not included any of the more recent finds, as published in Britannia, from 2006 onward). We focus on those inscriptions primarily from Volumes I and III of the RIB corpora to establish general trends about how people created dedications to British gods and Roman gods in public epigraphy. Volume II, which has recently been published digitally (Vanderbilt 2022), contains inscriptions on instrumentum domesticum, meaning that religious inscriptions from this volume pertain more to private worship than to the public religious landscape and are not examined here.

To investigate the nature and agency of public religious Latin epigraphy in Britain during the Roman period, we included in our dataset all religious dedications on all types of monuments, altars, dedication slabs, and building inscriptions, but not on tombstones. Religious dedications to deities were defined as those dedications that contained clear or mostly legible surviving epigraphic evidence for their purpose, with deities' names (in the dative) and, where available, the dedicators' names (in the nominative). We also included descriptions that mentioned a person 'fulfilling a vow', or an altar, even when a specific deity was not mentioned. To the best of our ability, we worked to include deities whose names were clearly mentioned, or, if not explicitly mentioned in the inscription, whose iconography was present on the stone. To analyse epigraphic agency more closely, we recorded the dedicator's gender and occupation when these details were discernible from the inscriptions. We determined gender by evaluating the gender of Latin endings to names and used gendered Latin pronouns when no names were present. Occupation (soldier or civilian) was only noted if explicitly included in the inscription. If the artefact containing the inscription was found in a fort (making it almost certain that it was dedicated by a soldier), but did not explicitly mention who dedicated it, we therefore included it as not mentioning an occupation. It is therefore likely that the overall percentage of stones dedicated by soldiers is much higher than we have counted. With all data collected here, however, we have included only what was actually carved on the stone, for all categories.

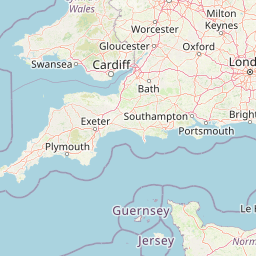

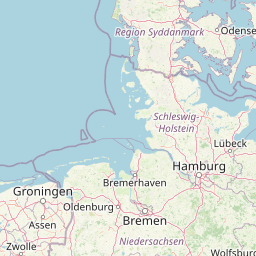

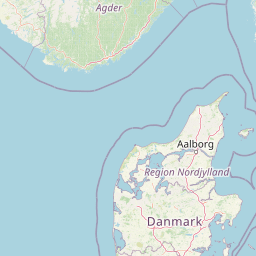

Three important caveats about the dataset we curated here must be addressed at the outset. First, many of the inscriptions in RIB Online cannot be dated beyond the 'Roman' period, unless the authority of specific consuls or emperors is listed. This is the case for most of the data studied here, where the date in RIB is given as 'A.D. 43-410'. The nature of the stone material upon which these inscriptions were cut further complicates any attempts at creating a material chronology from the items alone. While scholars previously working with this epigraphic data, especially Georgia Irby-Massie (1999), used the dating evidence available, we decided that the level of dating evidence was too small and inconsistent to be able to assist in answering our questions. Second, not all of the RIB corpora were found in situ. Many of the inscriptions were recovered from contexts of reuse and repurposing. For each inscription, we use the closest modern town to its original find-spot as the location for analysing general geographic trends in dedicatory inscription (see Figure 1 for a map of all RIB inscription locations studied in this text). Third, we only included inscriptions that fit these parameters because the surviving text indicates so. We did not include reconstructed or 'imagined' texts, especially on badly damaged stones where only one or two letters survived. Some of the stones have hypothesised or conjectured inscriptions based upon a single letter or the spacing of the text. In contrast to the policy of RIB Online, which includes some of these entries as religious inscriptions, we have not included them in this dataset because of the difficulty in interpreting such scanty evidence, especially on inscriptions, which used their own categories of formulae and abbreviations (Bodel 2010).

We created three categories to classify each religious inscription based on a larger cultural category of deities mentioned: inscriptions dedicated to deities from imported, Mediterranean or Eastern cults (MED); inscriptions to deities from local, British, and North-western European cults (LBNE); and inscriptions that contained some form of syncretism (SYN), either in dual-named interpretatio or by combining dedications to deities from MED and LBNE cultural traditions within the same inscription. These three categories—defined in more detail below, largely following classifications found in Birley 1986 and Irby-Massie 1999—allow us to trace how deities from different cultural traditions were invoked epigraphically. Our foundational framework for this article was to classify the deities by their original cultural context, even if their worship may have been introduced to Britain through military action. The goddess 'Britannia', for example, is classified under the MED category, because she represents the personification of the Roman military province, even though that province is the 'local' island. A complete list of the deities included in the MED or LBNE inscriptions can be found in Appendix 1. Those cases where we were unable to assign a deity to a particular group have been classified as 'Unknown' (UNK), a list of which can also be found in Appendix 1. In all cases, we have done our best given the limitations of the source material and the nature of our inquiry.

The study of Mediterranean deities in Britain allows us to trace how new religions and deities spread in the imperial province of Britain. Deities in this category include Greco-Roman deities such as Mars, Minerva, and the Imperial Cult, as well as deities with origins in more eastern regions of the empire (such as Mithras and Isis) that were brought into Britain after the conquest and/or are attested in the historical record by communities living in the Mediterranean and Eastern regions of the Roman Empire before Rome's conquest of north-western Europe (including Gaul, Germania, etc.). Inscriptions that contain the names of multiple Mediterranean deities were also included in this category.

This category is a broad conglomeration of pre-Roman and non-Roman deities whose names are primarily attested in the British Isles and north-western Europe (i.e. Hispania, Gaul, and/or Germania). The importance of trying to put MED and LBNE inscriptions into separate groups is to determine when a cult was more than likely brought into Britain from an external cultural context. It is easiest to see this for cults that are clearly Roman in origin, such as the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, or the Imperial Cult. It is also clear when eastern cults (such as those of Mithras, Isis, Serapis, etc.) were brought to Britain by the Romans.

It is much more difficult, however, when deities whose cult origin likely lies in the prehistoric 'Celtic' past of north-western Europe—deities whose worship is found in Britain as well as in Gaul, Germania, and/or Iberia. Loucetius Mars and Nemetona, for example, who are both known from one inscription in Britain (RIB 140) at Bath, are also worshipped together near the Rhine (Aldhouse-Green 2018, 226). Similarly, Viradecthis is known from one inscription in Britain (RIB 2108) at Birrens, but is also a protector deity of the Germanic tribe the Condrusi (Birley 1986, 76), to which the dedicators proclaimed their affiliation. In such cases, it is therefore difficult to parse out whether or not a cult that has worshippers in both Britannia and Germania should be considered truly foreign to the island (as with the Roman deities), and its presence in Britain may have simply been a result of the movement of peoples within the Roman army, or if it was truly local to Britain to begin with (before the Romans arrived and started using epigraphy). For example, (Ialonus) Contrebis is known from two inscriptions in Lancashire, one as Ialonus Contrebis (RIB 600 in Lancaster) and one as Contrebis (RIB 610 at Overborough). Ialonus' name appears elsewhere only once, on an inscription in Nîmes in Provence, and Contrebis' name comes from a district in Hispania Tarraconensis of the Celtiberi (see note in RIB 600). For this article, therefore, contra Irby-Massie 1999 and Birley 1986, we have chosen not to try to separate the cults in Britain from the cults in north-western Europe.

A good example of this is the Mother Goddesses (Matres) and related triads, which likely originated as part of a broader Celtic tradition in Germania and were brought to Britain with the Roman army (Haverfield 1892, 316; Irby-Massie 1999, 146). The Matres were adopted quickly and their cults spread widely after the Roman conquest of north-western Europe. Given the ties between pre-Roman Britain and Germania, we have made the decision to treat the larger 'Mother Goddesses', cult(s) as LBNE in origin, even though the mechanism of transmission may be the Roman army. We have therefore included the Matres Germanae, Matres Gallae, Matres Alatervae, Matres Suleviae, and Matres Britanniae as part of the LBNE cultural grouping. The only time this differs in our dataset is when an epithet of the Matres specifically refers to a region in the Roman Empire that is outside of north-western Europe—for example, the Matres Africae and Matres Itale. In the case of the Matres, our dataset therefore differs significantly from Irby-Massie's structure (1999, 146-149). While we agree that the Matres Africae and Matres Itale likely originated from elsewhere in the empire (Irby-Massie 1999, 146), outside of the sphere of LBNE cultural origins, we have included t/he Matres Communes, Matres Domesticus, Matres Omnium Gentium, Matres Ollotatae, and Matres Parcae as LBNE in origin, because nothing in their framing specifically requires that the goddesses invoked came from outside the LBNE cultural group. Haverfield, similarly, was not convinced that the Matres Parcae specifically was meant to call upon the Roman 'Parcae' (Fates), but rather considered that it might have been a convenient Latin word to use for a group of deities (of any cultural origin) who were thought to control the fates of humans (1892, 326-27).

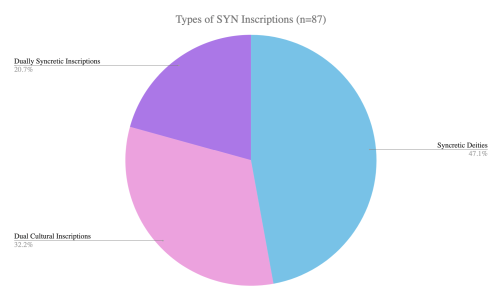

Inscriptions that we categorise as 'Syncretic' (SYN) contain within the surviving inscriptions the names of deities from both LBNE and MED cultural groups. This can happen on its own within the dual name of a deity (as a practice of interpretatio) (Zoll 1995b) or as part of an inscription to multiple separate deities. To approach the abstract process of religious syncretism methodologically and materially, we have created three subcategories of separate but related traditions of syncretism. For a complete list of SYN inscriptions (separated by subtype), see Appendix 1.

The first subcategory, which here we call Syncretic Deities (SD), have undergone interpretatio on the individual level, assumed into one deity, since the combined two names have been equated as one entity. Syncretic Deities are identifiable by their double names (Zoll 1995b)—Mars Belatucadrus, Sulis Minerva, and the like—one of whom is an attested deity from the Mediterranean world (usually part of the traditional Roman pantheon), and the other a deity from Britain specifically or the north-western provinces more broadly. In this article, Syncretic Deities are counted as separate entities from their eponymous LBNE singular deities. Although the individual deities are often attested on their own, the dual-named Syncretic Deities take on characteristics from multiple deities, making it inaccurate to count them as undifferentiated from the deities combined as Syncretic Deities. Therefore, for example, 'Belatucadrus' counts as LBNE, while 'Mars Belatucadrus' counts as Syncretic (but not LBNE) for our initial analysis of inscription groups.

Our second subcategory, Dual Cultural inscriptions (DC) encompasses inscriptions that include two or more distinct deities from different religious cultural groups in the same inscription: for example, an inscription to Jupiter (MED) and the Mother Goddesses (LBNE) (RIB 708). We consider this a method of syncretism because it evidences cross-cultural religious interaction. However, it achieves this by different means than the Syncretic Deity attestations because it does not blur the lines between the identities of the deities invoked, instead keeping them separate.

There are some inscriptions that belong to both Syncretic Deities and Dual Cultural categories, and they have been considered separately as Dually Syncretic inscriptions (DS). For example, RIB 1017 worships Jupiter (MED), Riocalatis (LBNE) Toutatis (LBNE), and Mars Cocidius (SD). RIB 1017 is therefore a Dually Syncretic inscription, because it contains not only a dedication to a Syncretic Deity (Mars Cocidius), but also dedications to LBNE deities (Riocalatis and Toutatis) and a MED deity (Jupiter). This example differs from most other Dually Syncretic inscriptions because it includes an individual MED deity and individual LBNE deities; other Dually Syncretic inscriptions tend to only include one or the other while also including a Syncretic Deity.

In some cases (e.g. Taranis), the deity is only represented epigraphically in syncretic contexts in the RIB data, though the historical record indicates that they were self-contained deities worshipped individually (Aldhouse-Green 2018, 100-3). Taranis never appears on his own in epigraphy in Britain, but he is understood from Lucan to have been a single deity who may have been worshipped throughout the Celtic world (Lucan, Pharsalia 1.445-446). Deities or epithets like Mars Camulus, Mars Corotiacus, and Apollo Cunomaglos, which appear to have their origins in Britain or the north-western provinces, only appear in syncretic contexts. There is no singular Camulus, Corotiacus, or Cunomaglos in the LBNE inscriptions. These deities will be discussed in Syncretic contexts only (see Appendix 1 for a complete list), and not as part of the LBNE group.

Some inscriptions are clearly dedications to a god or goddess (or both), but do not mention specific names of the deity or deities. This can happen either because the stone has been damaged, the deity was specifically not named (e.g. dedications only to 'deo' or 'deae'), or because the wording is vague and cannot be classified into a specific cultural context (e.g. RIB 1331, 'Lamiis tribus', 'the three witches').

We found 838 stones with religious inscriptions in the RIB Online data. The collective results for LBNE, MED, and SYN inscriptions are gathered in Table 1. These inscriptions are counted by the total number of stones with inscriptions, rather than by the number of individual dedications to deities upon each stone, as there are 151 stones (18%) with dedications to more than one deity.

| Inscription Types | TOTAL | Occupation | Gender | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soldier | Civilian | Sold. & Civ. | Unknown | Man | Woman | Both M & W | Unknown | ||

| MED* | 502

(59.9%) | 259

(51.6%) | 33

(6.6%) | 3

(0.6%) | 207

(41.2%) | 343

(68.3%) | 13

(2.6%) | 6

(1.2%) | 140

(27.9%) |

| LBNE | 197

(23.5%) | 51

(25.9%) | 12

(6.1%) | 0

(0.0%) | 134

(68.0%) | 123

(62.4%) | 5

(2.5%) | 3

(1.5%) | 66

(33.5%) |

| SYN | 87

(10.4%) | 38

(43.7%) | 8

(9.2%) | 0

(0.0%) | 41

(47.1%) | 72

(82.8%) | 2

(2.3%) | 1

(1.1%) | 12

(13.8%) |

| SD | 41

(4.9%) (47.1% of SYN) | 13

(31.7%) | 5

(12.2%) | 0

(0.0%) | 23

(56.1%) | 33

(80.5%) | 1

(2.4%) | 1

(2.4%) | 6

(14.6%) |

| DCI | 28

(3.3%) (32.2% of SYN) | 20

(71.4%) | 0

(0.0%) | 0

(0.0%) | 8

(28.6%) | 24

(85.7%) | 0

(0.0%) | 0

(0.0%) | 4

(14.3%) |

| DSI | 18

(2.1%) (20.7% of SYN) | 5

(27.8%) | 3

(16.7%) | 0

(0.0%) | 10

(55.6%) | 15

(83.3%) | 1

(5.6%) | 0

(0.0%) | 2

(11.1%) |

| UNK | 52

(6.2%) | 13

(25.0%) | 3

(5.8%) | 0

(0.0%) | 36

(66.7%) | 23

(44.2%) | 1

(1.9%) | 0

(0.0%) | 28

(53.8%) |

| TOTAL | 838 | 361

(43.1%) | 56

(6.7%) | 3

(0.4%) | 418

(49.9%) | 561

(66.9%) | 21

(2.5%) | 10

(1.2%) | 246

(29.4%) |

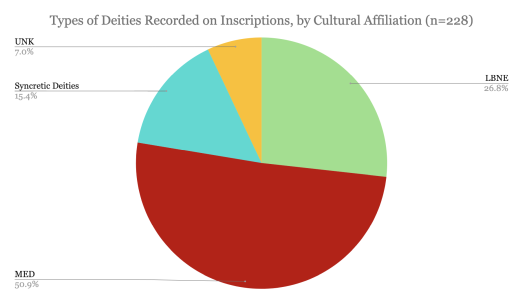

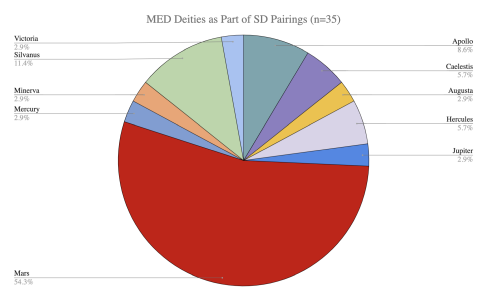

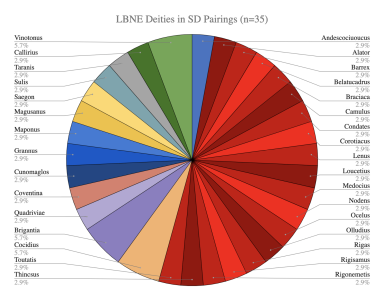

On these 838 stones, we have recorded 228 different deities (Appendix 1). Of these 228 deities, 35 are 'double-named' deities (Zoll 1995b)—such as Mars Belatucadrus—who are classified and described below as Syncretic Deities. Of the remaining 193 deities, 116 are classified as deities imported from the Mediterranean and the centre of the Roman Empire (MED), while 61 fall into a broad group of local, British, and north-western Europe cults (LBNE). Sixteen are of unknown origin (UNK), including inscriptions to deities who were not specifically named, or of inscriptions that are too damaged to be able to determine the deity who was originally invoked (Figure 2). Of the 838 stones, 225 included neither the dedicators' names nor any other information indicating their gender, occupation, or place of origin in the inscriptions.

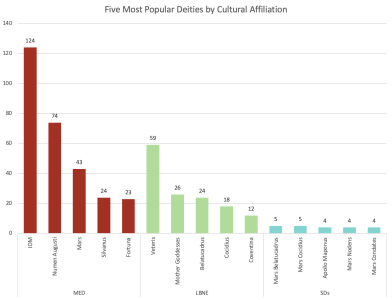

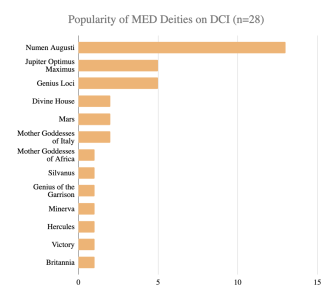

There are a total of 52 UNK inscriptions (6.2% of 838), on which the deity or deities named have no clear cultural affiliation (Table 1). MED inscriptions total 502, eight of which also contain the names of deities of 'unknown' cultural attribution, but do not include deities from the LBNE group. MED inscriptions comprise the majority (59.9%) of all religious inscriptions studied here. The seven most popular deities invoked in MED inscriptions are Jupiter Optimus Maximus (124 inscriptions), the Numen Augusti Imperial Cult (74 inscriptions), Mars (43 inscriptions), Silvanus (24 inscriptions), and Fortuna, Victory, and the Genius Loci (23 inscriptions each) (Figure 3).

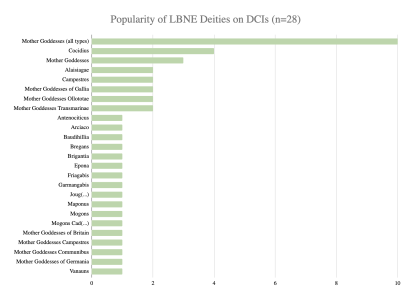

There are 197 LBNE inscriptions, dedicated only to gods from Britain and north-western Europe (23.5% of the total 838 religious inscriptions). Studying the attestation of these deities provides insight into how people living in Roman Britain utilised the newly introduced epigraphic technology to commemorate indigenous deities. The five most popular deities invoked in LBNE inscriptions are Veteris (in various spellings, alone in 58 inscriptions, as well as on one inscription to 'Mogons Vitiris'), the Matres or Mother Goddesses (26 inscriptions), Belatucadrus (24 inscriptions), Cocidius (18 inscriptions), and Coventina (12 inscriptions) (Figure 3). About half of the 61 LBNE deities (31, 50.8%) are only attested once in the entire corpus, with many others being recorded only two or three times. A further nineteen LBNE deities' names are attested only once and then only as part of Syncretic Deities (54.3% of all SDs).

There are only 87 inscriptions (10.4% of the total 838 religious inscriptions) that demonstrate any of the three kinds of religious syncretism we study here, and are classified as SYN inscriptions (Table 1). This category comprises quite a small fraction of the total religious inscriptions, suggesting that the practice was not particularly popular or widespread. The five most popular Syncretic Deities are Mars Belatucadrus and Mars Cocidius (5 inscriptions each), and Apollo Maponus, Mars Nodens, and Mars Condates (4 inscriptions each) (Figure 3).

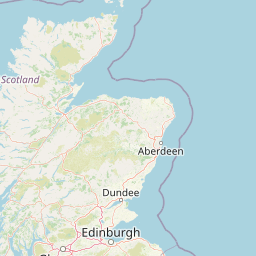

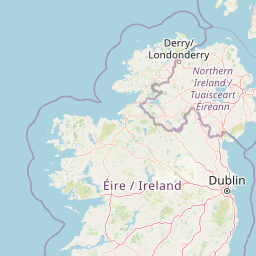

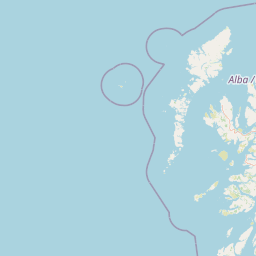

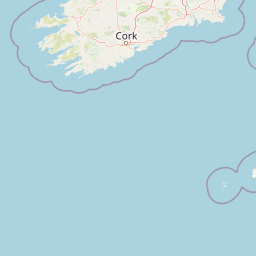

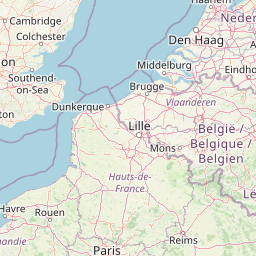

The complete map of all the dedicatory (religious or otherwise) inscriptions in the RIB Online (Figure 4) displays three geographical patterns. First, the religious inscriptions are concentrated largely in the north, adhering closely to the path of Hadrian's Wall, following results found by earlier scholars (Zoll 1995a; Biró 1975; Irby-Massie 1999). There are smaller clusters of inscriptions in the south-west of the island, and another set of inscriptions to the north around the Antonine Wall. Second, though inscriptions are rare in Wales (Biró 1975, 27) there are noticeably more MED inscriptions in Wales than any other cultural category. Third, there are notably far fewer religious inscriptions in the Midlands of Britain than anywhere else, as previous scholarship has noted (Biró 1975, 26). This pattern applies within all four MED, LBNE, SYN, and UNK categories as well as the overall dataset (Figure 4). When all inscriptions from Volumes I and III of RIB Online are mapped, that same sparsity in the Midlands is only slightly less noticeable (Figure 5). Recording any written text on publicly visible stone seems to have been an unappealing practice in this region, as very few public inscriptions of any type, religious or otherwise, were found in this area. The addition of Volume II to the RIB Online database has shown that people living in this area did in fact create inscriptions—the difference is that very few of these were made for public display (Vanderbilt 2022).

| At Forts | Not at Forts | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MED | 465 (92.6% of 502) (62.3% of 746) | 37 (7.4% of 502) (40.2% of 92) | 502 |

| LBNE | 174 (88.3% of 197) (23.3% of 746) | 23 (11.6% of 198) (25% of 92) | 197 |

| SYN | 63 (72.4% of 87) (8.5% of 746) | 24 (27.6% of 87) (26.1% of 92) | 87 |

| UNK | 44 (84.6% of 52) (5.9% of 746) | 8 (15.4% of 52) (8.7% of 92) | 52 |

| TOTAL | 746 (89.0% of 838) |

92 (11% of 838) | 838 |

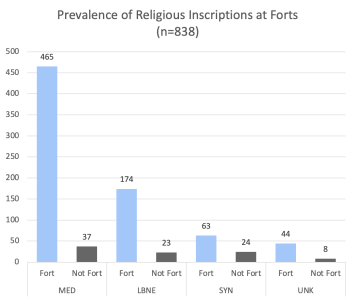

Of the 838 religious inscriptions studied here, a large majority (746, 89.0%) were found at or near Roman forts (Table 2, Figure 6). Fort proximity was determined by whether the findspot listed in RIB was recorded as a fort. In some instances, the RIB findspot did not record a fort, but records in Historic England, English Heritage, and the National Trust described forts at these sites, leading us to classify more inscriptions within this category. Overall, MED inscriptions were most likely to be found at forts (465 of 502 inscriptions, 92.6%), with LBNE inscriptions only slightly less likely (174 of 197 inscriptions, 88.3%), while SYN inscriptions were least likely to be found at forts (63 of 87 inscriptions, 72.4%) (Table 2, Figure 6). MED inscriptions form the majority of inscriptions found at forts, where they make up 62.3% of the total 746 inscriptions, while SYN inscriptions at forts are a clear minority, as they comprise 8.4% of the total. LBNE inscriptions are similar in prevalence at both fort (23.3%) and non-fort (25.0%) sites. At non-fort sites, MED inscriptions also comprise the largest category at 40.2% of the 92 inscriptions, but SYN and LBNE represent higher proportions of the total at 26.1% (n=24) and 25% (n=23), respectively (Table 2, Figure 7). Thus, religious inscriptions at non-fort sites were slightly more likely to be SYN or LBNE than they were to be dedicated to MED deities. Inscriptions found at forts are found across the island, but noticeably cluster at Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall, and are less densely distributed in the south (Figure 8). Inscriptions found at non-fort sites, in contrast, cluster more densely in the south, particularly in the Severn Valley and Cotswold region. All inscriptions found near the Antonine Wall come from fort sites.

Our first investigation of agency behind public votive inscriptions involves whether soldiers or civilians dedicated to particular types of deities. Nearly half of the 838 religious inscriptions (418, 49.9%) were dedicated by people whose occupation could not be established (Table 1, Figure 9). For MED and SYN inscriptions, occupation was mentioned on roughly half of the inscriptions. For LBNE inscriptions and UNK inscriptions, in contrast, only about a quarter of stones included the dedicator's occupation (Figure 9). Where the occupation was described in the dedication, the overwhelming majority (361, 43.1% of 838) of the dedications were put up by soldiers (Table 1, Figure 9). This is true not only for the total dataset, but also for each of the cultural categories.

Civilians participated in monumental religious epigraphic dedications, but in comparatively smaller numbers (Table 1, Figure 9). Only 56 (6.7%) were dedicated by civilians, and groups that represent soldiers and civilians joined forces to dedicate three MED inscriptions [RIB 1136 (Corbridge), RIB 722 (Bainbridge) and RIB 005 (London)], but did not collaborate on inscriptions in any of the other categories. The largest quantity of civilian inscriptions were to MED deities (n=33), but this represents only 6.6% of all MED inscriptions. The eight SYN inscriptions by civilians make up a slightly higher percentage of SYN inscriptions (9.2%). Civilians were less involved in creating an overall proportion of LBNE inscriptions (12 inscriptions, 6.1% of LBNE inscriptions) and UNK inscriptions (3 inscriptions, 5.8% of the 52 UNK inscriptions).

Despite the fact that there were more than six times as many inscriptions by soldiers as by civilians, both occupation groups created MED, LBNE, SYN, and UNK inscriptions in relatively similar proportions (Figure 10). MED inscriptions were the most popular choice by both civilians (58.9% of their inscriptions) and soldiers (71.8% of their inscriptions), though civilians were slightly more likely to create inscriptions to LBNE, SYN, and UNK deities than soldiers. The largest category of inscription type by people of unknown occupations was MED inscriptions (with 207 inscriptions, 49.4%). Those people with uncertain occupations were just as likely to create non-MED inscriptions as MED inscriptions. Generally, therefore, there is an overwhelming preference for MED inscriptions among soldiers, civilians, and soldiers and civilians acting together, though this majority is less well established for people who did not leave details about their occupations.

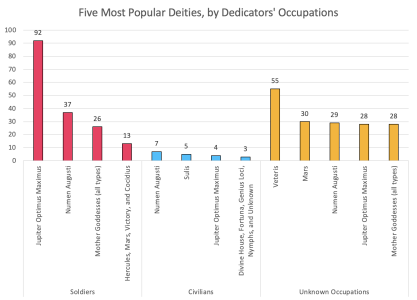

Soldiers, civilians, and people who did not identify their occupation dedicated to different gods within the cultural groups. The five most numerous deities (with many tight ties) for each occupation group are shown in Figure 11. Jupiter Optimus Maximus and the Numen Augusti appear as two of the most popular deities for all occupation groups. Mars and variations of the Mother Goddesses were popular among soldiers and people with uncertain occupations, but not for civilians. The most popular deity attested by people with uncertain occupations is Veteris. Dedications to this deity rarely included information about the dedicators, so the agency behind the creation of inscriptions to this god is obscured. Civilians, in addition to Jupiter Optimus Maximus and the Numen Augusti, were most likely to invoke Sulis, the Divine House, Genii Loci, and Nymphs in their inscriptions. While all occupation groups were likely to dedicate to deities related to imperial power, soldiers and people who did not mark their occupation were more likely to dedicate to deities associated with the army or to the Mother Goddesses, while civilians were more likely to invoke deities associated with specific places or natural features.

The majority trend in geographical patterning for all inscriptions is a higher concentration at Hadrian's Wall, with less dense distribution south of the Wall (Figure 4a, Figure 12). The distribution of inscriptions by soldiers (Figure 12a), compared to those by civilians (Figure 12b), mirrors the geographical pattern of inscriptions at forts versus inscriptions at sites without forts. Inscriptions by soldiers cluster most noticeably near Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall, while inscriptions by civilians cluster less visibly by Hadrian's Wall and are more evenly distributed across the southern half of the island. Inscriptions by civilians are found at both Walls, however, and are not significantly less densely distributed in the southern half of the island compared to inscriptions by soldiers in the same area. When comparing the map of all inscriptions by soldiers (n=361, Figure 12a), to the map of all inscriptions by people with uncertain occupation (n=418, Figure 12d), it is noticeable that there are more inscriptions by people with uncertain occupations in the southern half of the island, especially in the Cotswolds and Severn Valley regions, than there are inscriptions by soldiers.

Certain occupation groups and dedications to different deity cultural groups break this pattern, and we highlight these here. MED inscriptions by soldiers and by people of uncertain occupation have similar geographic distributions to each other, as well as to the overall dataset (Figure 13a–d). They are found in larger quantities around Hadrian's Wall, but are also distributed across the island. MED inscriptions by civilians, however, are distributed relatively equally at the Wall and across Britain south of the Wall (Figure 13b–c). Interesting distribution patterns also emerge when looking at the occupational agency behind LBNE and SYN dedications (Figs 13 and 14). All of the LBNE inscriptions made by soldiers (51, 14.1% of inscriptions by soldiers) were found in the north near Hadrian's Wall, while there was a more even distribution of LBNE inscriptions by civilians: six of the twelve were located at Bath in the Severn Valley, three are in the north of England, and the remaining three were found near Hadrian's Wall (Figure 14). Similarly, SYN inscriptions by soldiers were primarily found in the north around Hadrian's Wall, with some across the southern half of the island and at the Antonine Wall. Noticeably, there were no SYN inscriptions by civilians at Hadrian's Wall: there were two at the Antonine Wall and six in the southern third of the island, from Nettleton to Colchester (Figure 15). This suggests that the agency behind syncretic epigraphy was not uniform across the entire island, and that while it happened in the militarised region of Hadrian's Wall, civilians who lived near it did not participate in public religious epigraphy that merged local gods with new ones imported with the army. This pattern may indicate some level of contingency upon chronological factors, since the Antonine Wall was only occupied for a few decades in the mid-2nd century.

The distribution of UNK inscriptions, of all the cultural categories, clusters most noticeably around Hadrian's Wall, with only a few outliers at the Antonine Wall and in the southern half of the island (Figure 16). All UNK inscriptions by soldiers or civilians cluster at Hadrian's Wall, the Antonine Wall, and in the region between them (Figure 16a–b). Only 5 of the 52 UNK inscriptions are found south of Hadrian's Wall, and all of these are by people with uncertain occupations (Figure 16c). This could suggest that at these military zones, people wanted not only to dedicate to the Roman gods of the military conquest, but also to leave space intentionally open to gods of all cultural origins, a deliberately inclusive act rather than an exclusive or dominating one.

Civilian inscriptions included details about occupations and identities, and can provide insight into different communities living in Roman Britain. Twenty-one civilian inscriptions were made by women and 13 were made by freedmen. Other civilian groups appear on no more than three inscriptions each. Civilian occupations include: priests and priestesses, a guild treasurer, a merchant, a sculptor, a stonemason, a doctor, an aedile, and a haruspex, among others.

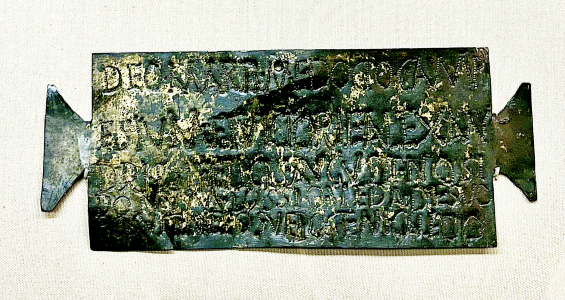

Inscriptions by freedmen warrant further exploration. Eleven of the 13 inscriptions created by freedmen included the names of the people whose households the freedmen used to belong to and who eventually freed them. One such inscription, RIB 193, is particularly interesting in what it can tell us about social mobility in Roman Britain. The altar was found in Colchester, which was a civitas capital (Biró 1975, 15). Unfortunately, the stone has been lost since its 1764 find date, but sketches and records remain. The RIB entry proposes that the dedicator, Imilico, had an African name, though Martin Henig contends that he may have been Celtic (Henig 1984, 57). Imilico accrued enough wealth to commission the construction of a marble altar that stood at nearly half a metre tall. One word, maronio, has been translated in RIB as 'marble', which would insinuate that maronio was an error for marmorio (see note for RIB 193). The inscription states that Imilico raised the funds for its creation himself. Not only could Imilico afford a customised altar made of marble, he could also afford to have it inscribed to explicitly state that it was made of marble, which comes as a surprise considering that the material upon which these religious inscriptions were cut was very rarely included in the inscription text. His altar commemorates the Numen Augusti and Mercury Andescociuoucus. The name Andescociuoucus is elsewhere unattested, though scholars have noted Celtic elements in the etymology (see commentary in RIB 193; Iliceto 2009, 83).

Civilian dedications sometimes insinuate or explicitly state connections between civilian communities and the Roman army. Three inscriptions (RIB 899, RIB 1700, and RIB 3503) were created by vicus residents living near the military forts of Maglona (Old Carlisle, Wigton), Vindolanda (Hexham), and Veluniate (Carriden) respectively, the first two of which are on Hadrian's Wall. The last is from the Antonine Wall, in Caledonia (RIB 3503) and is dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and it states that a man by the name of Aelius Mansuetus funded the project on behalf of the vicus residents. It is unclear whether or not Mansuetus was a soldier or a civilian, and there is a possibility that he created this dedication for the benefit of the villagers rather than as a result of consultation with them, though the inscription describes how the villagers "paid their vow" ("v[otum] s[olverunt])"; on this phrase, see Pearce 2023, 195-196), so there was likely some degree of collaboration.

RIB 1700 is an inscription to Vulcan, the Divine House, and Numen Augusti. This combination of deities is markedly Roman, with the specific worship of the Emperor and the imperial family. This inscription was found adjacent to another inscription to Jupiter Optimus Maximus (RIB 1689), a further connection to the Roman state religion. By creating RIB 1700, the villagers may have wished to demonstrate their loyalty to the Roman soldiers who protected them and contributed greatly to their local economy. The inclusion of Vulcan may hint about the day-to-day roles of the vicus villagers; they may have executed a fair amount of smithing on behalf of the army and wished to pay homage to the god of smiths. RIB 899 is also dedicated to Vulcan and created by villagers from a vicus. It was found at the site of a Roman fort, so it is likely that the inscription was made by the villagers living near that fort. Jupiter Optimus Maximus is also included on this inscription, reinforcing the interpretation that the proximity between RIB 1700 and RIB 1689 may have been an intentional choice. There were a further three civilian inscriptions created by smiths, though the deities mentioned on these included Minerva, Neptune, and the Divine House (MED); (RIB 91); Silvanus Callirius (SD) (RIB 194); and the Genius Loci (MED) (RIB 712); but not Vulcan.

Though civilians were slightly more likely to create SYN and LBNE inscriptions than soldiers, the majority of their inscriptions still follow the same paradigm as that of the soldiers: they are dominated by MED deities, particularly those championed by the Roman state. Thus, despite not being members of the Roman military complex, civilians were welcome and likely even encouraged to participate in the creation of epigraphy to Roman state deities. The consistency of deities included on vicus inscriptions may indicate that the people living in the vici felt compelled to create dedications to the Roman deities who guided the army and protected their village. It could also imply some degree of external influence in the choice to include these specific deities—perhaps the soldiers at Veluniate, Vindolanda, and Maglona played a role in encouraging the residents of their respective vici to create these inscriptions and advised them on which deities were most appropriate to include.

Since the majority of the 838 inscriptions were created by soldiers, it is unsurprising that men dedicated the large majority (66.9%) of the inscriptions, while only 21 (2.5%) were made by women and ten (1.2%) by both men and women. About a third of inscriptions were unclear as to the dedicators' gender (246, 29.4%) (Table 1, Figure 17). This overall pattern remained almost exactly the same for the MED and LBNE categories, where roughly two-thirds of inscriptions were dedicated by men, women acting alone dedicated less than 3%, and about one-third of the dedications did not include the gender of the dedicator (Figure 17). People who created SYN dedications were more likely to leave information about gender in the inscription, compared with MED and LBNE inscriptions, as only 12 SYN inscriptions did not include any information as to gender (13.8%) (Table 1, Figure 17). Women participated in this syncretic epigraphy at roughly the same proportion as in MED and LBNE inscriptions: two were made by women (2.3%), and one (RIB 213, to Mars Corotiacus, at Martlesham) was made by both a man and a woman (1.2%). Men more visibly contributed to syncretic epigraphy (82.8% of SYN inscriptions) (Figure 17). In contrast, the majority of people dedicating to deities of uncertain cultural origin did not leave information denoting their gender (53.8%), and only one of the 52 was made by a woman.

Men and women dedicated inscription types in relatively similar proportions (Figure 18), despite the fact that comparatively few women were responsible for those dedications. Both groups primarily created dedications to MED deities. Women were slightly less likely than men to create SYN inscriptions, and slightly more likely than men to create LBNE inscriptions. When men and women collaborated on inscriptions, they were more likely to create inscriptions to LBNE deities than men acting alone, women acting alone, or people whose gender is unknown. People whose gender could not be established were most likely to create inscriptions to deities with unknown cultural affiliations.

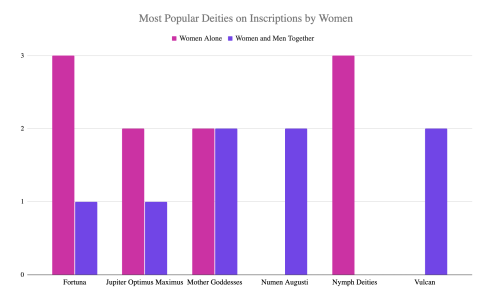

There is no clear pattern regarding the deities to which women dedicated. Only six deities received more than two inscriptions by women. Women acting alone dedicated three inscriptions to Nymphs, while men and women acting together dedicated two inscriptions each to the Numen Augusti and Vulcan. Women also participated in the creation of four inscriptions to variations of Mother Goddesses, a further four to variations of Fortuna, and three to Jupiter Optimus Maximus (Appendix 2, Figure 19). These were not the same deities who were most popularly attested in the entire corpus (Figure 3). Fortuna, the Mother Goddesses, and Nymphs are themselves feminine, a further contrast from the overall dataset, wherein the majority of the most popular deities from each cultural group were masculine (Figure 3).

It appears that though generally epigraphy was not a popular technology for religious dedications among women, when they did create religious inscriptions, they felt free to commemorate the deities of their choice. Rather than making many inscriptions to a small number of deities, they created a small number of dedications to a wide array of deities. Women acting on their own dedicated 21 inscriptions involving 20 different deities (Appendix 2). Six of these dedications were to gods who appear nowhere else in the dataset, so women alone were responsible for public votive inscriptions to these gods (the Celestial Silvanae, Heracles of Tyre, Mars Pacifier, Contrebis, Apollo Cunomaglos, and the Celestial Quadruviae). Women acting alone created dedications in a noticeably different manner than men and women acting together, the latter category comprising ten inscriptions dedicated to twelve different deities. Women and men acting together invoked three deities who appear nowhere else in the dataset: Gallia (RIB 3332), Sattada (RIB 1695), and Mars Corotiacus (RIB 213). They also made inscriptions to Bonus Eventus, the Divine House, the Deified Emperor, the Numen Augusti, Vulcan, and the Mother Goddesses Ollotatae, none of which received votive inscriptions from women acting alone.

It is not surprising, given the larger geographical clustering of all 838 inscriptions near Hadrian's Wall, that the inscriptions by men and by people whose gender cannot be established cluster closest to Hadrian's Wall, as well as the Antonine Wall. There is some distribution across the southern half of the island as well, and inscriptions on the southern coast of England tend to be dedicated by men (Figure 20a). The relatively small number of all inscriptions that involve women, whether on their own or with men, these are more evenly distributed across the island (Figure 20b and 20c). Inscriptions by women cluster more in the north near the Wall, but to less of an extent than inscriptions by men or by people with undetermined gender. These patterns are similar for MED inscriptions across all gender categories (Figure 21).

LBNE and SYN differ from MED and overall patterns in terms of gendered agency. For LBNE inscriptions by men and by people whose gender cannot be established there is, once again, a noticeable cluster near Hadrian's Wall, while for LBNE inscriptions by women and both men and women, there is no geographical preference: they are present at the Wall and in the southern half of the island in relatively equal numbers (Figure 22). The map of all SYN inscriptions by men (Figure 23a) follows the pattern for inscriptions by men in general, clustering at the Wall but present across the island. The three SYN inscriptions involving women were not found near Hadrian’s Wall: two were in the south of the island (including one by a woman and a man acting together) and one was near the Antonine Wall (Figure 23). One of the two SYN inscriptions by women acting alone is at at Westerwood, Cumbernauld (RIB 3504, see also Ferlut 2022), and one is at Nettleton in Wiltshire (RIB 3053). Much like our findings for civilians participating in epigraphic religious syncretism, not only did women choose unique deities, they also refrained from making these inscriptions in the expected area around Hadrian's Wall, which has been noted as the central focus for the creation of all religious inscriptions.

For UNK inscriptions, there is a noticeable clustering at Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall for those by men and those by people with undetermined gender. The one inscription to an unknown deity by a woman is found at Carrawburgh (RIB 1539) (Figure 24b). It is interesting to note that while women dedicating MED or UNK inscriptions were likely to do so near Hadrian's Wall, they were less likely to dedicate LBNE inscriptions there and did not do so at all for SYN inscriptions. This suggests that women were less able or less comfortable dedicating to their local or locally syncretised deities in militarised zones.

Inscriptions made by women can reveal information about their positions in society and shed light on both interpersonal relationships and perceived relationships between women and the deities for whom they created dedications. Of the 31 inscriptions that demonstrate women's agency in religious epigraphy, six of them (19.4%) describe the women's relationship to men in their lives by giving their fathers' and husbands' names. A particularly peculiar inscription found at Risingham, RIB 1228, does not include the name of the woman who created the dedication at all, but simply refers to her as '(she) who is married to Fabius'. This woman chose to not identify herself in epigraphy by her given name, but rather by her relationship to her husband. The inscription states that an unnamed soldier had a dream that led him to instruct the unnamed woman in question to create an altar to the Nymphs. The text is in dactylic hexameter (see note in RIB 1228), indicating that this woman may have been familiar with Latin metric conventions. The textual content of this inscription raises the question of the extent of the woman's agency in its creation: did she formulate this text herself, or did a soldier give her explicit instructions for the content of the inscription? This example highlights that when focusing on the specific agency of women in religious epigraphy, the agency of Roman soldiers is still quite palpable. Whose agency is recorded in this inscription?

Another inscription, RIB 1729, was dedicated to a pluralised form of the deity Veteris (Veteres) by a woman named Romana. The etymology and current scholarly understanding of this deity are both complicated, and versions of the name appear with variable spelling 59 times across the dataset (including once as Mogons Vitiris). There is no consensus on the gender and number of this deity, and the Veteres may have been a plural deity like the Matres or Suleviae (Birley 1986, 62; Irby-Massie 1999, 105-7; Zoll 2014, 630-32). With only one exception (RIB 971 to 'Mogons Vitiris', counted here as an LBNE inscription), Veteris is never combined with any other deity as part of a dual-named Syncretic Deity, nor is Veteris included with any MED deities in other syncretic inscriptions.

RIB 1729 is the only inscription to Veteris or the Veteres explicitly dedicated by a woman. It was found at Aesica Roman Fort in Great Chesters (modern Haltwhistle), on the western side of Hadrian's Wall. Two other inscriptions to Veteris or the Veteres were also found at Great Chesters (RIB 1728 and RIB 1730), the former with the deity in a singular form and the latter in a pluralised form. Neither of these, however, leave information about the dedicator's gender, occupation, or place of origin. Romana's inscription commemorates a likely local deity whose name appears primarily near Hadrian's Wall. Her name is quite obviously Roman in origin, and she may have lived in the civilian vicus adjacent to the Roman fort. Her choice to create a dedication to a local deity in an environment dominated by the Roman army may be a testament to the army's religious tolerance. It could equally be interpreted as a result of military influence on and potential introduction of the technology of public religious epigraphy, which Romana used to commemorate a local deity.

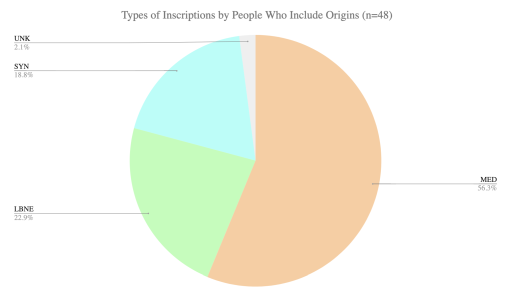

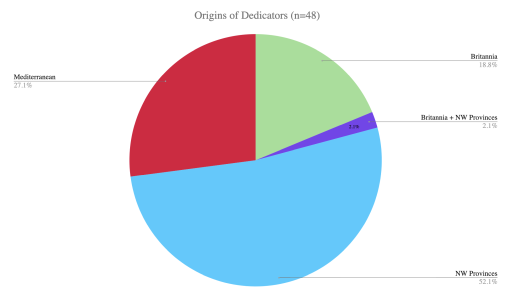

Of the 838 inscriptions, only 48 recorded the dedicator's origins (Appendix 3). We categorised these into three subcategories: people from Britannia, people from the North-western Provinces (Gaul, Hispania, Germania), and people from the Mediterranean (Italy, Anatolia, North Africa, etc.). While these 48 inscriptions represent only 5.7% of the total epigraphic corpus studied here, they provide an illuminating window into local agency using this new technology of worship. Importantly for our understanding of gendered agency, no women listed their place of origin (Appendix 3).

Overall, these 48 dedications included 27 MED inscriptions (56.3%), eleven LBNE inscriptions (22.9%), nine SYN inscriptions (18.8%), and one UNK inscription (2.1%) (Table 3, Figure 26). The majority of these 48 inscriptions were dedicated by people from the North-western Provinces (25 inscriptions, 52.1%), while people from Britannia and the Mediterranean dedicated in roughly similar numbers (18.8% and 27.1%) (Table 3, Figure 27). MED inscriptions are the most popular in each category of origin (Table 3). SYN inscriptions were the most likely to include the dedicator's place of origin (10.3%, n=9/87), while UNK were the least likely (1.9%, n=1/52) and MED and LBNE were roughly equally as likely (5.4%, n=27/502 and 5.6%, n=11/197, respectively).

| MED | LBNE | SYN | UNK | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Britannia | 6 (66.7%) 🔵🔵🔵🔵⚫🟡 | 2 (22.2%) 🔵🟡 |

1 (11.1%) 🟡 |

- | 9 (18.8%) 🔵🔵🔵🔵🔵⚫ 🟡🟡🟡 |

| NW Provinces | 10 (40%) 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 🔵🟡🟡🟡 | 8 (32%)🔴🔴🔴🔵🟡🟡 🟡🟡 |

6 (24%) 🔴🔴🔵🟡🟡🟡 |

1 (4%) 🔴 | 25 (52.1%) 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 🔵🔵🔵🟡🟡🟡 🟡🟡🟡🟡🟡🟡 🟡 |

| NW Provinces + Britannia |

1 (100%) 🟡 | - | - | - | 1 (2.1%) 🟡 |

| Mediterranean |

10 (76.9%) 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 🔴🔴🔴🔴 | 1 (8.3%) 🔴 |

2 (16.7%) 🔴🔴 | - | 13 (27.1%) 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 🔴 |

| TOTAL | 27 (56.3% of 478) 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴🔴 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔵🔵 🔵🔵🔵⚫🟡🟡 🟡🟡🟡 | 11 (22.9% of 48) 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔵🔵 🟡🟡🟡🟡🟡 | 9 (18.8% of 48) 🔴🔴🔴🔴🔵🟡 🟡🟡🟡 |

1 (2.1% of 48) 🔴 | 48 |

Occupation and place of origin are directly related to the type of inscription that people dedicated (Table 3). All people from the Mediterranean who dedicated inscriptions were soldiers. Soldiers who mentioned their origins in inscriptions were roughly as likely to have come from the Mediterranean (13) than the North-western Provinces (12). People from the North-western Provinces displayed the most variety in epigraphic habits, as these included ten MED, eight LBNE, six SYN, and one UNK inscriptions, and were dedicated by twelve soldiers, three civilians, and ten people with unknown occupations (Table 3, Figure 28). Of note, 16 of these 25 inscriptions were created explicitly by people from Germania. This accounts for a third of all inscriptions where dedicators left details of their origins, thus the largest proportion of people from any given region to do so. People from Germania seem to have been proud of their heritage, and wished to include it on their inscriptions. In terms of recorded agency between people of different geographical, ethnic, or cultural origins on public religious epigraphy, there are (very broadly) two groups: people from the island of Britain, who were unlikely to be soldiers, and people who moved to the island as part of the army. Neither of these two groups, however, was more likely than the other to dedicate to any particular type of deity (Table 3).

Importantly for our understanding of local British, participation in the religious epigraphic habit, people from Britannia were unlikely to list their occupation. Four of the inscriptions made by civilians from Britain (RIB 899, 1700, 288, and 3503) listed that they were dedicated by vicus villagers or civitas residents, and a fifth (RIB 1695) was made by 'the assembly of Textoverdi', a local tribal group from northern Britain. None of the people from Britannia recorded that they were soldiers (Table 3). We know Britons joined the Roman army eventually (Cunliffe 2013, 398), but they may have been deployed to other provinces, hence the absence of local soldiers in our data. Another possibility is that local soldiers chose to omit an explicit mention of their homeland or tribal affiliations. Alternatively, some of the three dedicators from Britain with uncertain occupations could have been soldiers, but chose not to include information regarding their occupation on inscriptions where they stated their affiliations to local communities.

People from Britain mostly created MED inscriptions (Table 4). Six of the nine are MED inscriptions, two are LBNE inscriptions, and one is a SYN inscription (DCI). Three inscriptions by Britons record the only attestations of their respective deities in the entire dataset: Mars Medocius (RIB 191), the Mother Goddesses Suleviae (RIB 192), and Sattada (RIB 1695). When local people created public votive inscriptions and included their place of origin, they usually did so in groups, rather than as individuals recording their own names. Of the nine inscriptions explicitly made by people from Britain, only two were made by individuals, while the other six were made by collectives of villagers and hunters, assemblies, and in one case (RIB 005), the entire province. Because they frequently created inscriptions in groups, five of the eight inscriptions were created with the collaboration of men and women. Inscriptions by local people were more likely to have been made with the collaboration of men and women than in any other category of dedicators' origins. Three were created by men alone, and one by a person of unknown gender. This small group of inscriptions created by explicitly local dedicators therefore contrasts with the findings from our other subcategories. Where generally men (and particularly soldiers) dominated public religious epigraphic production across the island, when locals created dedications, they were more frequently collaborations between men and women, and they often included no mention of military affiliations.

| RIB | Mention of Origins | Inscription Type | Deities | Occupation | Gender | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 005 | 'province of Britain' | MED | Numen Augusti | soldiers + civilian | men + women | London |

| 191 | a Caledonian | SYN (DSI) | Victoria Augusta, Mars Medocius | unknown | men | Colchester |

| 192 | a tribesman of the Cantiaci | LBNE | Mother Goddesses Suleviae | unknown | men | Colchester |

| 899 | the villagers of 'Mag…' [Maglona] | MED | Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Vulcan | civilian | men + women | Wigton |

| 288 | Civitas of Cornovians | MED | Deified Emperor | civilian | men + women | Wroxeter |

| 1695 | the assembly of the Textoverdi | LBNE | Sattada | civilian | men + women | Hexham |

| 1700 | the villagers of Vindolanda | MED | Vulcan, Divine House, Numen Augusti | civilian | men + women | Hexham |

| 1905 | the hunters of Banna | MED | Silvanus | unknown | unknown | Gilsland |

| 3503 | the villagers at Veluniate | MED | Jupiter Optimus Maximus | unknown | men | Carriden |

Different inscription types seem to have different distribution patterns according to the origins of their dedicator (Figure 29). MED inscriptions for all origins are present both at Hadrian's Wall and elsewhere in Britain. There are noticeably more MED inscriptions by people from the Mediterranean at Hadrian's Wall than elsewhere on the island, however, following larger dataset trends for MED inscriptions. Most of the eleven LBNE inscriptions for which origins were recorded occur at Hadrian's Wall or further north, with two exceptions (RIB 192 to the Matres Suleviae at Colchester and RIB 149 to Sulis at Bath) (Figure 29c). SYN inscriptions, when origins were recorded, occurred sporadically across the island, as far north as Hadrian's Wall, but there is no clear geographic preference (Figure 29d). When LBNE, SYN, and UNK inscriptions have origins recorded, people with Mediterranean origins created inscriptions at Hadrian's Wall and in northern Britain, while people from Britain and the North-western Provinces dedicate these inscription types across the island (Figs 29c–d).

Inscriptions by people recording their Mediterranean origins show up most notably near Hadrian's Wall in the north of England, with two exceptions, in the south-west at Caerleon (RIB 324) and at Castlecary (RIB 2148) on the Antonine Wall (Figure 30a). This could suggest that people who immigrated to the island from the Mediterranean thought it was important to dedicate to local or locally-syncretised gods in militarised zones, perhaps in an effort to either conquer or connect with the local populations. The geographic distribution of the nine dedications by people from Britain vary across the island (Figure 30b), with three at Hadrian's Wall (RIB 1695, 1700, and 1905), three in the south-east (RIB 005 at London and RIB 191 and 192 at Colchester), one in the midwest (RIB 288 at Wroxeter), and one (RIB 3503) at Carriden. Dedications by people from the North-western Provinces are found across the island, especially at Hadrian's Wall (Figure 30c).

Our research agrees with what much previous scholarship has noted: that public religious epigraphy was an especially prevalent practice in the north of Britain and by Hadrian's Wall. The comprehensive map of the 838 religious dedicatory inscriptions in the RIB Online data demonstrates a comparative paucity of such epigraphy in the Midlands, stretching from Wales to Norfolk on the eastern coast of England, possibly limited by the availability of carvable stone in the region (Birley 1986, 103; Zoll 2014). The region may have had significant areas where religious epigraphy on stone was rarely, if ever, encountered. This trend persists across all subcategories of religious inscriptions explored in this article: MED, LBNE, UNK, and SYN. The people living in the Midlands therefore participated in public religious practices by means other than Latin epigraphy on stone. This promotes a model of regional choice, whereby groups from different regions chose whether they wished to create religious inscriptions or not. Stone may have been difficult or expensive to move, and the people living in this region chose not to do so.

We have found that MED inscriptions are not only the most popular category overall, but are also the most popular category at both fort and non-fort sites. There is a noticeable preference for MED inscriptions, in particular, at forts in militarised zones and frontier regions such as Hadrian's Wall, the Antonine Wall, and Wales. In contrast, SYN inscriptions are three times more likely to be found at non-fort sites than at fort sites. When inscriptions of any type are found at non-fort sites, those sites are more often in the southern half of Britain than in the north.