Cite this as: Root, C., Kay, J.E., Kreike-Martin, N., Weng, C., Madsen, H. and Pare, R. 2024 The Agency of Civilians, Women, and Britons in the Public Votive Epigraphy of Roman Britain, Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.17

The Roman army has long been understood to have been centrally responsible for the spread of Roman religious material culture and practices in Britain, especially in public epigraphic contexts. The epigraphic corpus, especially Roman Inscriptions of Britain (RIB) (Vanderbilt 2022), provides some of the best evidence for understanding what role individual agency played in religious practice, because many of the inscriptions record the occupation, gender, or origins of the dedicator. Despite the fact that public religious epigraphy in Roman Britain is overwhelmingly militarised and masculine, as well as an imported technology of conquest, it still offers a unique opportunity to investigate alternative perspectives. We examine how the worship of native deities survived in public Latin epigraphy, either on their own or in a syncretic context, and how civilians, women, and local Britons participated in this new technology of worship, especially relating to newly imported deities. We track three large categories: inscriptions to deities imported from the Mediterranean with the Roman conquest of Britain; inscriptions to deities whose origin or cult centre likely lies in Britain or the north-west provinces (e.g. Germania, Gallia and Hispania); and inscriptions that invoke deities from both cultural categories, especially through processes of syncretism and cross-cultural exchange. We catalogued, restructured, and interrogated the data from the RIB Online database, examining the geographical context and textual contents of the public religious inscriptions from Volumes I and III. In agreement with previous studies of military religion, we find that civilians and local Britons were not prolific contributors to the public Latin epigraphic tradition and imperial soldiers held primary agency in inscriptions to local deities on the island. This influence is particularly visible in the militarised area around Hadrian's Wall, where Roman soldiers created more religious inscriptions than dedicators from any other occupation - a pattern found throughout the province. The agency of civilians, women, and people from Britain, however, changed according to the cultural affiliation of the deities to whom they dedicated, as well as the location of the inscriptions. People dedicating to deities whose worship was focused in Britain or north-western Europe were less likely to include information about their occupations (especially military connections) than were people dedicating to deities imported from the Roman Mediterranean (including Eastern mystery cults). On inscriptions that involved religious syncretism, civilians (and especially men, who were overwhelmingly responsible for this category) were particular about how this syncretism was executed in the text, always incorporating interpretatio and making no inscriptions that keep the deities' identities separate. Significantly, while Hadrian's Wall seems to have acted as the cradle of religious epigraphy in Roman Britain, civilians (and therefore, women) did not create syncretic epigraphy in this area.

Charlotte A. Root

Princeton University

Corresponding author: Janet E. Kay

jekay@princeton.edu

Princeton University

Noah Kreike-Martin

Princeton University

Cathleen Weng

Princeton University

Heather Madsen

Princeton University

Rhiannon Pare

Princeton University

Figure 1: Map showing all known locations for the inscriptions studied, marked to the nearest modern town

Figure 2: Pie Chart of all 228 deities commemorated in the 838 inscriptions, according to cultural affiliation of the deities (for list, see Appendix 1)

Figure 3: Bar chart showing the most popular deities in the MED, LBNE, and Syncretic Deities categories

Figure 4a: Map of all religious inscriptions (n=838)

Figure 4b: Map of all MED inscriptions (n=502)

Figure 4c: Map of all LBNE inscriptions (n=197)

Figure 4d: Map of all SYN inscriptions (n=87)

Figure 4e: Map of all UNK inscriptions (n=52)

Figure 5a: The complete map of all 838 religious RIB inscriptions studied in this article, clustered in order to be comparable with the complete RIB data shown to the right

Figure 5b: The complete map of all inscriptions (n=959) categorised in the RIB Online database as 'Text Type: Religion' and 'Object Type: Monumental' (as of 22 September 2024). Inscriptions are clustered because that is the default format from the RIB Online database (Vanderbilt 2022)

Figure 6: Bar chart showing relative proportions of whether inscriptions were found at forts, by each inscription type

Figure 7a: Pie chart showing relative percentages of all inscriptions found at fort sites according to inscription type

Figure 7b: Pie chart showing relative percentages of all inscriptions found at non-fort sites according to inscription type

Figure 8a: Map of inscriptions found at fort sites (n=746)

Figure 8b: Map of inscriptions not found at fort sites (n=92)

Figure 9a: Pie chart showing relative percentages of occupations of dedicators for all religious inscriptions (n=838)

Figure 9b: Pie chart showing relative percentages of occupations of dedicators for all MED inscriptions (n=502)

Figure 9c: Pie chart showing relative percentages of occupations of dedicators for all LBNE inscriptions (n=197)

Figure 9d: Pie chart showing relative percentages of occupations of dedicators for all SYN inscriptions (n=87)

Figure 9e: Pie chart showing relative percentages of occupations of dedicators for all UNK inscriptions (n=52)

Figure 10a: Pie chart showing relative percentages of inscriptions dedicated by soldiers, according to inscription type (n=361)

Figure 10b: Pie chart showing relative percentages of inscriptions dedicated by civilians, according to inscription type (n=56)

Figure 10c: Pie chart showing relative percentages of inscriptions dedicated by [soldiers + civilians], according to inscription type (n=3)

Figure 10d: Pie chart showing relative percentages of inscriptions dedicated by people of unknown occupation, according to inscription type (n=419)

Figure 11: Bar chart showing the five most popular deities for soldiers, civilians, and dedicators with unknown occupation

Figure 12a: Distribution map of all inscriptions by soldiers (n=361)

Figure 12b: Distribution map of all inscriptions by civilians (n=56)

Figure 12c: Distribution map of all inscriptions by [soldiers + civilians] (n=3)

Figure 12d: Distribution map of all inscriptions by people with unknown occupation (n=418)

Figure 13a: Distribution map of all MED inscriptions by soldiers alone (n=259)

Figure 13b: Distribution map of all MED inscriptions by civilians alone (blue, n=33) and [soldier + civilian] (purple, n=3)

Figure 13c: Distribution map of all MED inscriptions by people of unknown occupation (n=207)

Figure 14a: Distribution map of all LBNE inscriptions by soldiers (n=51)

Figure 14b: Distribution map of all LBNE inscriptions by civilians (n=12)

Figure 14c: Distribution map of all LBNE inscriptions by people of uncertain occupation (n=134)

Figure 15a: Distribution map of all SYN inscriptions by soldiers (n=38)

Figure 15b: Distribution map of all SYN inscriptions by civilians (n=8)

Figure 15c: Distribution map of all SYN inscriptions by people of uncertain occupation (n=41)

Figure 16a: Distribution map of all UNK inscriptions by soldiers (n=13)

Figure 16b: Distribution map of all UNK inscriptions by civilians (n=3)

Figure 16c: Distribution map of all UNK inscriptions by people of uncertain occupation (n=36)

Figure 17a: Pie chart showing relative percentages of dedicators’ gender for all religious inscriptions (n=838)

Figure 17b: Pie chart showing relative percentages of dedicators'’' gender for all MED inscriptions (n=502)

Figure 17c: Pie chart showing relative percentages of dedicators’ gender for all LBNE inscriptions (n=197)

Figure 17d: Pie chart showing relative percentages of dedicators’ gender for all SYN inscriptions (n=87)

Figure 17e: Pie chart showing relative percentages of dedicators’ gender for all UNK inscriptions (n=52)

Figure 18a: Pie chart showing relative percentages of inscriptions dedicated by men, according to inscription type (n=561)

Figure 18b: Pie chart showing relative percentages of inscriptions dedicated by women, according to inscription type (n=21)

Figure 18c: Pie chart showing relative percentages of inscriptions dedicated by [men + women], according to inscription type (n=10)

Figure 18d: Pie chart showing relative percentages of inscriptions dedicated by people of unknown gender, according to inscription type (n=247)

Figure 19: Bar chart of the most popular deities attested on inscriptions by women, comparing dedications by women alone and dedications made with the collaborative efforts of men and women

Figure 20a: Map of all inscriptions by men (n=561)

Figure 20b: Map of all inscriptions by women (pink) (n=21) and [men + women] (purple) (n=10)

Figure 20c: Map of all inscriptions by people whose gender cannot be determined (n=246)

Figure 21a: Map of all MED inscriptions by men (n=343)

Figure 21b: Map of all MED inscriptions by women (pink) (n=13) and [men + women] (purple) (n=10)

Figure 21c: Map of all MED inscriptions by people whose gender cannot be determined (n=140)

Figure 22a: Map of all LBNE inscriptions by men (n=123)

Figure 22b: Map of all LBNE inscriptions by women (pink) (n=5) and [men + women] (purple) (n=3)

Figure 22c: Map of all LBNE inscriptions by people whose gender cannot be determined (n=66)

Figure 23a: Map of all SYN inscriptions by men (n=72)

Figure 23b: Map of all SYN inscriptions by women (pink) (n=2) and [men + women] (purple) (n=1)

Figure 23c: Map of all SYN inscriptions by people whose gender cannot be determined (n=12)

Figure 24a: Map of all UNK inscriptions by men (n=23)

Figure 24b: Map of all UNK inscriptions by women (pink) (n=1)

Figure 24c: Map of all UNK inscriptions by people whose gender cannot be determined (n=28)

Figure 25: Bar chart showing ways women identify themselves in religious epigraphy, including: one or two names, mothers and daughters inscribing together, if they made inscriptions in collaboration with men, and if they included their relationships to men in their families

Figure 26: Pie chart showing the relative types of inscriptions by the collective total of people (n=48) who included their location of origin in their religious inscriptions

Figure 27: Pie chart showing the origins of people who included such information in their religious inscriptions (n=48)

Figure 28: Bar chart that shows relative counts of origins within inscription cultural categories

Figure 29a: Map of all inscriptions where origins were specifically mentioned (n=48)

Figure 29b: Map of MED inscriptions for which origins were recorded (n=27) - Dot colours represent origins: red for Mediterranean, green for Britannia, blue for North-western Provinces, purple for [North-western Provinces + Britannia], yellow for Unknown

Figure 29c: Map of LBNE inscriptions for which origins were recorded (n=11) - Dot colours represent origins: red for Mediterranean, green for Britannia, blue for North-western Provinces, purple for [North-western Provinces + Britannia], yellow for Unknown

Figure 29d: Map of SYN (n=9) and UNK (n=1) (RIB 2151 at Castlecary on the Antonine Wall) inscriptions for which origins were recorded (n=27) - Dot colours represent origins: red for Mediterranean, green for Britannia, blue for North-western Provinces, purple for [North-western Provinces + Britannia], yellow for Unknown

Figure 30a: Map of dedications by people from Mediterranean (n=13) - Dot colours represent inscription types: orange for MED, green for LBNE, blue for SYN, yellow for Unknown

Figure 30b: Map of dedications by people from Britannia (n=9) - Dot colours represent inscription types: orange for MED, green for LBNE, blue for SYN, yellow for Unknown

Figure 30c: Map of dedications by people from North-western Provinces (n=25) - Dot colours represent inscription types: orange for MED, green for LBNE, blue for SYN

Figure 30d: Map of dedications by people from [Britannia + North-western Provinces] (n=1, RIB 3332 at Vindolanda) - Dot colours represent inscription types: orange for MED

Figure 31: Pie chart showing relative percentages of the three different subtypes that make up the total of SYN inscriptions (n=87) (Syncretic Deities, Dual Cultural inscriptions, and Dually Syncretic inscriptions)

Figure 32: Pie chart showing relative percentages of how often individual MED deities appear in SD pairings (n=35) within the dataset

Figure 33: Pie chart showing relative percentages of how often individual LBNE deities appear in SD pairings (n=35) within the dataset - The deities shaded red on the right half of the chart were paired with Mars. Brigantia and the Quadriviae were paired with Caelestis and are shaded purple. The three blue-shaded deities on the left were paired with Apollo, and the two yellow deities above them were paired with Hercules

Figure 34: Horizontal bar chart showing number of times an individual MED deity was invoked in the 28 Dual Cultural inscriptions

Figure 35: Horizontal bar chart showing number of times an individual LBNE deity was invoked in the 28 Dual Cultural inscriptions

Figure 36a: Map of all inscriptions to Syncretic Deities (n=41)

Figure 36b: Map of all Dual Cultural inscriptions (n=28)

Figure 36c: Map of all Dually Syncretic inscriptions (n=18)

Figure 37a: Pie chart showing relative percentages of occupations of dedicators for all Syncretic Deity inscriptions (n=41)

Figure 37b: Pie chart showing relative percentages of occupations of dedicators for all Dual Cultural inscriptions (n=28)

Figure 37c: Pie chart showing relative percentages of occupations of dedicators for all Dually Syncretic inscriptions (n=18)

Figure 38a: Pie chart showing relative percentages of SYN subcategory dedications made by soldiers (n=38)

Figure 38b: Pie chart showing relative percentages of SYN subcategory dedications made by civilians (n=8)

Figure 38c: Pie chart showing relative percentages of SYN subcategory dedications made by people of unknown occupation (n=38)

Figure 39a: Map of all Syncretic Deity inscriptions dedicated by soldiers (n=13)

Figure 39b: Map of all Syncretic Deity inscriptions dedicated by civilians (n=5)

Figure 39c: Map of all Syncretic Deity inscriptions dedicated by people of unknown occupation (n=23)

Figure 40: Map of all Dual Cultural inscriptions dedicated by soldiers (n=20) (red) and people of unknown occupation (n=8) (yellow)

Figure 41: Map of all Dually Syncretic inscriptions dedicated by soldiers (n=5) (red), civilians (n=3) (blue), and people of unknown occupation (n=10) (yellow)

Figure 42: Chart showing the counts of the three different SYN subcategories dedicated by people of different genders

Figure 43a: Pie chart showing relative percentages of dedicators' gender for all Syncretic Deity inscriptions (n=41)

Figure 43b: Pie chart showing relative percentages of dedicators' gender for all Dual Cultural inscriptions (n=28)

Figure 43c: Pie chart showing relative percentages of dedicators’ gender for all Dually Syncretic inscriptions (n=18)

Figure 44a: Map of all Syncretic Deity inscriptions dedicated by men (n=33) (blue), women (n=1) (pink), [men + women] (n=1) (purple), and people of unknown gender (n=6) (yellow)

Figure 44b: Map of all Dual Cultural inscriptions dedicated by men (n=33) (blue) and people of unknown gender (n=6) (yellow)

Figure 44c: Map of all Dually Syncretic inscriptions dedicated by men (n=33) (blue), women (n=1) (pink), and people of unknown gender (n=6) (yellow)

Figure 45a: Map of all SYN inscriptions showing origins of dedicators (n=9) - Dot colours represent dedicators' origins: red for Mediterranean, green for Britannia, blue for North-western Provinces

Figure 45b: Map of all Syncretic Deity inscriptions showing origins of dedicators (n=2) - Dot colours represent dedicators' origins: red for Mediterranean and blue for North-western Provinces

Figure 45c: Map of all Dual Cultural inscriptions showing origins of dedicators (n=2) - Dot colours represent dedicators' origins: blue for North-western Provinces

Figure 45d: Map of all Dually Syncretic inscriptions showing origins of dedicators (n=5) - Dot colours represent dedicators' origins: red for Mediterranean, green for Britannia, and blue for North-western Provinces

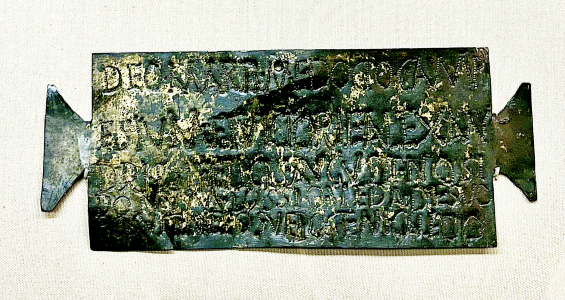

Figure 46: RIB 191, bronze plate dedicated to Mars Medocius of the Campeses by Lossio Veda, a Caledonian. Currently displayed in the British Museum (1892,0421.1), originally found in Colchester. Photo by C. Root

Table 1: Total counts of each inscription type (MED, LBNE, SYN, and UNK), including counts of each SYN subtype (SD, DCI, DSI). Each type is broken down by occupation and gender. Italic percentages represent the row total, not the 838 total.

Table 2: Breakdown of inscription categories according to whether or not they were found at fort sites

Table 3: Cultural types of inscription according to the recorded origins of the dedicators. Percentages in italics represent the percentage of the row total

Table 4: Inscriptions by people who specifically mention geographical origins or ethnic or tribal affiliation

Table 5: Depicts the breakdown of SYN inscription subcategories according to whether or not they were found at fort sites

Table 6: SYN sub-types of inscription according to the recorded origins of the dedicators

Aldhouse-Green, M.J. 2018 Sacred Britannia: The Gods and Rituals of Roman Britain, London: Thames & Hudson.

Aldhouse Green, M. and Raybould, M.E. 1999 'Deities with Gallo-British names recorded in inscriptions from Roman Britain, Studia Celtica 33, 91-135.

Allason-Jones, L. 2005 Women in Roman Britain, 2nd edition, York: Council for British Archaeology.

Allason-Jones, L. 2012 'Women in Roman Britain', in S.L. James and S. Dillon (eds) A Companion to Women in the Ancient World, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. 467-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444355024.ch34

Allason-Jones, L. 2023 The Hinterland of Hadrian's Wall and Derbyshire, Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani, Great Britain, Vol. 1, Fasc. 11, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ando, C. 2005 'Interpretatio Romana', Classical Philology 100(1), 41-51. https://doi.org/10.1086/431429

Ando, C. 2008 The Matter of the Gods: Religion and the Roman Empire, Oakland: University of California Press.

Ando, C. 2010 'The ontology of religious institutions', History of Religions 50(1), 54-79. https://doi.org/10.1086/651726

Bell, C.E. 2020 Investigating the Autonomy of Power: Epigraphy of Women in Roman Britain, MA thesis, University of Liverpool.

Birley, A.R., Hekster, O. and de Kleijn, G. 2007 'The frontier zone in Britain: Hadrian to Caracalla' in L. de Blois and E. Lo Cascio (eds) The Impact of the Roman Army (200 B.C.-A.D. 476), Leiden: Brill. 355-70. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004160446.i-589.57

Birley, E. 1986 'The deities of Roman Britain', Teilband Religion 18(1), 3-112. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110861464-002

Biró, M. 1975 'The inscriptions of Roman Britain', Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 27, 13-58.

Bodel, J. 2010 'Epigraphy' in A. Barchiesi and W. Scheidel (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Roman Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 107-22. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199211524.013.0007

Bowman, A. 1998 Life and Letters on the Roman Frontier: Vindolanda and its People, New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203823699

Collingwood, R.G. 1923 'The British frontier in the age of Severus', Journal of Roman Studies 13, 69-81. https://doi.org/10.2307/295743

Collingwood, R.G. and Wright, R.P. 1965 The Roman Inscriptions of Britain: Volume I, Inscriptions on Stone, Oxford: Clarendon.

Collingwood, R.G. and Wright, R.P. 1990-95 The Roman Inscriptions of Britain: Volume II, Instrumentum Domesticum, S.S. Frere and R.S.O. Tomlin (eds), Gloucester: Alan Sutton Publishing.

Collins, R.M. 2007 Decline, Collapse, or Transformation? Hadrian's Wall in the 4th-5th Centuries AD, PhD thesis, University of York. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/9945/

Cousins, E.H. 2020 The Sanctuary at Bath in the Roman Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108694735

Creighton, J. 2000 Coins and Power in Late Iron Age Britain, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489587

Cunliffe, B.W. 2013 Britain Begins, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Daubney, A. 2010 'The cult of Totatis: evidence for tribal identity in mid Roman Britain' in S. Worrell, G. Egan, J. Naylor, K. Leahy and M. Lewis (eds) A Decade of Discovery: Proceedings of the Portable Antiquities Scheme Conference 2007, Brit. Archaeol. Rep. British Series 520, Oxford: Archaeopress. 109-20.

De Bernardo Stempel, P. 2008 'Continuity, translatio and identification in Romano-Celtic religion: the case of Britain' in R. Haeussler and A.C. King (eds) Continuity and Innovation in Religion in the Roman West, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 67(2). 67-82.

Derks, T. 1991 'The perception of the Roman pantheon by a native elite: the example of votive inscriptions from Lower Germany' in N. Roymans and F. Theuws (eds) Images of the Past: Studies on Ancient Societies in Northwestern Europe, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press. 235-65.

Ferlut, A. 2022 'The Quadruviae: cult mobility and social agency in the northern provinces of the Roman Empire' in T. Gallopin, E. Guillon, M. Luaces, A. Lätzer-Lasar, S. Lebreton, F. Porzia, J. Rüpke, E. Rubens Urciuoli and C. Bonnet (eds) Naming and Mapping the Gods in the Ancient Mediterranean: Spaces, Mobilities, Imaginaries, Berlin: De Gruyter. 313-34. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110798432

Fishwick, D. 1961a 'The Imperial Cult in Roman Britain', Phoenix 15(1), 159-73. https://doi.org/10.2307/1086674

Fishwick, D. 1961b 'The Imperial Cult in Roman Britain (continued)', Phoenix 15(4), 213-29. https://doi.org/10.2307/1086734

Fraser, J.E. 2009 From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795, Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9780748612314.001.0001

Gardner, A. 2013 'Thinking about Roman imperialism: postcolonialism, globalisation and Beyond?', Britannia 44, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X13000172

Goldberg, D.M. 2009 'The dichotomy in Romano-Celtic syncretism: some preliminary thoughts on vernacular religion' in M. Driessen, S. Heeren, J. Hendriks, F. Kemmers and R. Visser (eds) TRAC 2008: Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Amsterdam 2008, Oxford: Oxbow Books. 187-202. https://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC2008_187_202

Green, M. 1976 A Corpus of Religious Material from the Civilian Areas of Roman Britain, Brit. Archaeol. Rep. British Series 24, Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

Haensch, R. 2007 'Inscriptions as sources of knowledge for religions and cults in the Roman world of imperial times' in J. Rüpke (ed) A Companion to Roman Religion, Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 176-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470690970.ch13

Haverfield, F. 1892 'The Mother Goddesses', Archaeologia Aeliana (series 2) 15, 314-39. https://doi.org/10.5284/1059638

Hemelrijk, E.A. 2012 'Public roles for women in the cities of the Latin West' in S.L. James and S. Dillon (eds) A Companion to Women in the Ancient World, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. 478-90. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444355024.ch35

Henig, M. 1984 Religion in Roman Britain, London: Routledge.

Hodgson, N. 2014 'The British expedition of Septimius Severus', Britannia 45, 31-51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X1300055X

Hope, V. 1997 'Words and pictures: the interpretation of Romano-British tombstones', Britannia 28, 245-58. https://doi.org/10.2307/526768

Hope, V. 2014 'Inscriptions and identity' in M. Millett, L. Revell, and A. Moore (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 285-82. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697731.013.018

Hübner, S. 2018 'Frauen und Schriftlichkeit im römischen Ägypten' in A. Kolb (ed) Literacy in Everyday Ancient Life, Berlin: De Gruyter. 163-78. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110594065-009

Iliceto, A. 2009 Aspetti di Vita Quotidiana, Religiosa, Militare e Civile in Britannia e Lungo il Vallo di Adriano, PhD Thesis, Università di Bologna.

Irby-Massie, G.L. 1996 'The Roman army and the cult of the Campestres', Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 113, 293-300.

Irby-Massie, G.L. 1999 Military Religion in Roman Britain, Boston: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004351226

Jackson, R. 2020 The Roman Occupation of Britain and Its Legacy, London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350149410

James, S. 1999 'The community of the soldiers: a major identity and centre of power in the Roman Empire' in P. Baker, C. Forcey, S. Jundi and R. Witcher (eds) TRAC 98: Proceedings of the Eighth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Leicester 1998, Oxford: Oxbow Books. 14-25. https://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC1998_14_25

MacMullen, R. 1982 'The epigraphic habit in the Roman Empire', The American Journal of Philology 103(3), 233-46. https://doi.org/10.2307/294470

Madsen, J.M. 2018 'Between autopsy reports and historical analysis: the forces and weaknesses of Cassius Dio's Roman History', Lexis 36, 284-304.

Mann, J.C. 1974 'The northern frontier after A.D. 369', Glasgow Archaeological Journal 3, 34-42. https://doi.org/10.3366/gas.1974.3.3.34

Mann, J.C. 1985 'Epigraphic consciousness', Journal of Roman Studies 75, 204-6. https://doi.org/10.2307/300660

Mattingly, D.J. 2006 An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire,London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Millett, M. 1990 The Romanization of Britain: An Essay in Archaeological Interpretation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moorhead, S. and D. Stuttard 2016 The Romans Who Shaped Britain, Thames & Hudson.

Mullen, A. 2010 'Linguistic evidence for "Romanization": Continuity and change in Romano-British onomastics: a study of the epigraphic record with particular reference to Bath', Britannia 38, 35-61. https://doi.org/10.3815/000000007784016548

Ostler, N. 2008 Ad Infinitum: A Biography of Latin, New York: Walker Publishing Company, Inc.

Pearce J. 2023 'Encounters with writing in the sanctuaries of Roman Britain' In P. Barnwell and T. Darvill (eds) Places of Worship in Britain and Ireland, Prehistoric and Roman periods, Rewley House Studies in the Historic Environment Vol. 8, Donington: Shaun Tyas. 187-219.

Pearce, J. 2024 'An empire of words? Archaeology and writing in the Roman world' in J.Tanner and A. Gardner (eds) Materialising the Roman Empire, London: UCL Press. 45-75. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.6914759.10

Radman-Livaja, I. 2021 'The population of Siscia in the light of epigraphy' in A.W. Irvin (ed) Community and Identity at the Edges of the Classical World, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 47-62. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119630746.ch3

Raybould, M.E. 1999 A Study of Inscribed Material from Roman Britain: An Inquiry into Some Aspects of Literacy in Romano-British Society, Brit. Archaeol. Rep. British Series 281, Oxford: Archaeopress. https://doi.org/10.30861/9780860549864

Saller, R.P. and Shaw, B.D. 1984 'Tombstones and Roman family relations in the Principate: civilians, soldiers and slaves', Journal of Roman Studies 74, 124-56. https://doi.org/10.2307/299012

Salway, P. 1965 The Frontier People of Roman Britain, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tomlin, R.S.O. 2002 'Writing to the gods in Britain' in A. Cooley (ed) Becoming Roman, Writing Latin? Literacy and Epigraphy in the Roman West, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 48. 165-79.

Tomlin, R.S.O. 2018a 'Literacy in Roman Britain' in A. Kolb (ed) Literacy in Everyday Ancient Life, Berlin: De Gruyter. 201-19. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110594065-011

Tomlin, R.S.O. 2018b Britannia Romana: Roman Inscriptions and Roman Britain, Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Tomlin, R.S.O., Wright, R.P. and Hassall, M.W.C. 2009 The Roman Inscriptions of Britain , Volume III: Inscriptions on Stone, found or notified between 1 January 1955 and 31 December 2006, Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Vanderbilt, S. 2022 Roman Inscriptions of Britain Online. https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org

Versluys, M.J. 2014 'Understanding objects in motion. An archaeological dialogue on Romanization', Archaeological Dialogues 21(1), 1-20.

Webster, J. 1995 '"Interpretatio": Roman word power and the Celtic gods', Britannia 26, 153-61. https://doi.org/10.2307/526874

Wedlake, W.J. 1982 The Excavation of the Shrine of Apollo at Nettleton, Wiltshire, 1956-1971, London: Society of Antiquaries of London.

Williams, J. 2007 'New light on Latin in pre-conquest Britain', Britannia 38, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3815/000000007784016386

Woolf, G. 1996 'Monumental writing and the expansion of Roman society in the early Empire', Journal of Roman Studies 86, 22-39. https://doi.org/10.2307/300421

Woolf, G. 2013 'Ethnography and the gods in Tacitus' Germania' in E. Almagor and J. Skinner (eds) Ancient Ethnography: New Approaches, London: Bloomsbury Academic. 133-52.

Zoll, A. 1995a 'A view through inscriptions: the epigraphic evidence for religion at Hadrian's Wall' in J. Metzler, M. Millett, N. Roymans and J. Slofstra (eds) Integration in the Early Roman West: The Role of Culture and Ideology: Papers Arising from the International Conference at the Titelberg (Luxembourg) 12-13 November 1993, Luxembourg: Musée National d'Histoire et d'Art. 129-37.

Zoll, A. 1995b 'Patterns of worship in Roman Britain: double-named deities in context', in S. Cottam, D. Dungworth, S. Scott and J. Taylor (eds) TRAC 94: Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Durham 1994, Oxford: Oxbow Books. 32-44. https://doi.org/10.16995/TRAC1994_33_44

Zoll, A. 2014 'Names of gods' in M. Millett, L. Revell, A. Moore (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 619-40. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697731.013.034

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.