Curator, Vindolanda Trust, Bardon Mill, Hexham, NE47 7JN, UK.

Email: barbarabirley@vindolanda.com

Cite this as: Birley, B. 2016 Keeping Up Appearances on the Romano-British Frontier, Internet Archaeology 42. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.42.6.6

Roman Vindolanda lies on the Stanegate Road to the south of Hadrian's Wall, on the northern frontier of the Romano-British province. It has complex stratigraphy with at least ten layers of occupation dating from around AD 85 to its abandonment in the 5th century, but it is the first five levels from AD 85 to AD 130-139 that have produced some of the most significant organic objects from the Empire, including the Vindolanda writing tablets (Birley 2009). One of the distinctive aspects of the Vindolanda collection is the large number of wooden hair combs found in these levels.

Over 160 boxwood hair combs have been unearthed from the site. Resembling modern nit combs, these small objects had the primary function of cleaning and detangling hair, but further examination of the collection allows for the exploration of different aspects of style and function.

Common box (Buxus sempervirens) was popular during Roman times, due to its smooth but hard nature, and was sought after for making not only combs but many other objects (Pliny 16, 70: trans. Rackham 1968). It does not splinter and catch the hair, and it can be dulled at the point, which stops the comb from injuring the scalp. Indeed, in classical literature, the term 'buxus' is often used for combs (Pugsley 2003, 21).

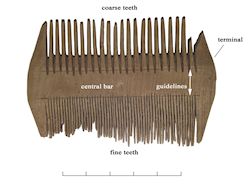

All of the combs in the Vindolanda collection are the so-called 'H combs', named because they resemble the letter H. The vertical lines of the H are the terminals and the horizontal line is the central bar. The H comb has two sets of teeth, one fine and the other coarse. Guidelines have been placed on most for accurate carving but on some examples the carver has gone over the lines (Figure 1).

The identifying marks on the combs most often appear on the central bar. The objects can show decorations, makers' marks or graffiti. Decorated central bars can include many different motifs, including waves, stars, lines and circle-in-circle patterns. Many use more than one form of decoration.

The Vindolanda collection shows a greater variation of central bar adaptation and decoration than many other collections (Derks and Vos 2010; Fellmann 2009; Pugsley 2003). This could indicate the desire that personal combs should be identifiable. As these objects were undoubtedly used to help with the removal of head lice, which would have been prevalent within a military community (Fell 1991; Mumcuoglu and Hadas 2011), the ability to mark individual combs would have been useful to reduce the spread of parasites.

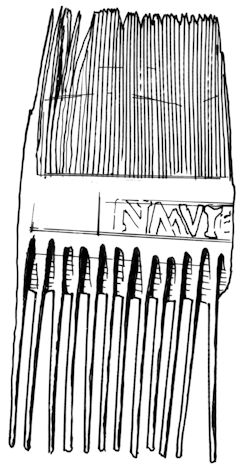

The makers' marks are very faint and are best seen through magnification. The collection at Vindolanda currently includes seven combs that have makers' marks. These are usually located on the central bar and state the name of the individual maker (Figure 2). Most of the combs with stamps have been marked on both sides of the comb. It is also noticeable that these combs are of very high quality, possibly showing that the maker only wanted to identify with superior work.

Some of the combs from the collection show other forms of modification. Three combs have holes drilled through at the top, presumably for suspension. This would have been a functionally efficient way to attach your comb, avoid loss and prevent others from using it. One of the combs from Vindolanda shows that it was originally a standard H comb but its coarse teeth, and probably the terminals, were intentionally removed, leaving a decorative comb that could have been worn in the hair.

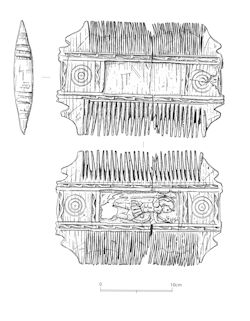

However, the most elaborate comb from the collection is an example with fretted terminals and a highly decorative central bar (Figure 3). Here, a very thin copper-alloy plaque depicts a standing figure in military dress, complete with shield and spear (Blake 2014, 95). The reverse may also originally have had a plaque, but this has not survived. A similar comb was found in Carlisle, but on this the copper-alloy plaque represented three conjoining aediculae, separated by twisting columns and framing images of deities (Pugsley 2003, 22).

Roman boxwood combs have been found not only in Romano-British contexts including London, Carlisle and Ribchester (Pugsley 2003, 145-150) but also in other parts of the empire, including Vetchen (modern Holland: Derks and Vos 2010), Vindonissa (modern Switzerland: Fellmann 2009, 68-69) and eastern provinces including modern Israel (Mumcuoglu and Hadas 2011, 226-227). An increasing body of evidence shows that these objects were more common than once perceived. Questions have been raised, such as who was using them and whether they were part of the woman's mundus muliebris (toiletries box), or of the grooming ritual of men (Derks and Vos 2010). Evidence from Vindolanda would suggest both. Numerous research projects have looked at sexing material culture within Roman forts (Allason-Jones 1995; Allison 2015), including case studies from Vindolanda (Birley 2013; Driel-Murray 1992; 1997). This evidence is dispelling the myth that the Roman military was a male-only society and is showing that both women and children were present in large numbers on the frontier.

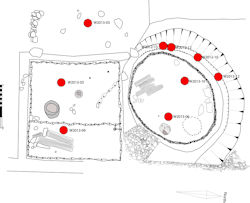

Two wooden buildings dating to c.AD 105-120 were uncovered during the excavations in 2012/2013. The first was a circular house with a small ditch to the north and west. The other was a rectilinear building with a later modification of a cross wall. The buildings were situated in between the fort wall and the Stanegate Road. The findspots for the nine wooden combs from this area are shown in Figure 4. Also from here were over 80 leather boots and shoes (belonging to both genders), large caches of buried hazelnuts in sealed pits, preserved animal bones, pre-Hadrianic pottery, brooches, perfume bottles, hairpins, beads, styli, stylus tablets, ink pens and an ink tablet. The combs come from the rubbish deposits outside the buildings and inside probable single-family residences. This distribution could be interpreted as the result of both casual loss and intentional removal from the house. Combined with the other objects from these contexts, they speak of a rich material culture, literacy and access to imported goods, as well as objects that were probably used by both men and women.

These small portable pieces of material culture would have been easy for an individual to pack and carry when their garrison was moved on to a new post. They also show that the people here had disposable income, and that the money spent on these functional but imported luxury goods was significant to the people at Vindolanda. Cleanliness was important to them, as we see from other objects and the use of bathhouses on the frontier (Allason-Jones 1999), but combs also relate to the ritual of the everyday, and show that dressing one's hair was an important signifier of identity, whether soldier or non-combatant, male or female.

Allason-Jones, L. 1995 ''Sexing' small finds', Theoretical Roman Archaeology: Second Conference Proceedings, Worldwide Archaeology Series, Vol. 14, Aldershot: Avebury/Ashgate. 22-32

Allason-Jones, L. 1999 'Healthcare in the Roman North', Britannia 30. 133-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/526676

Allison, P.M. 2015 'Characterizing Roman artifacts to investigate gender practices in context without sexed bodies', American Journal of Archaeology 119(1), Archaeological Institute of America. 102-123.

Birley, A. 2013 'The fort wall: a great divide?', in R. Collins and M. Symonds (eds), Breaking Down Barriers, Hadrian's Wall in the 21st century, Journal of Roman Archaeology supplementary series 93. 85-104.

Birley, R. 2009 Vindolanda, a Roman Frontier Fort on Hadrian's Wall, Stroud: Amberley.

Blake, J. 2014 The Excavations of 2007-2012 in the Vicus or Extramural Settlement, Brampton: Roman Army Museum Publications.

Derks, D. and Vos, W. 2010 'Wooden combs from the Roman fort of Vechten: the bodily appearance of soldiers', Journal of Archaeology in the Low Countries 2, 53-57.

Driel-Murray, C. van, 1992 'Gender in question', Theoretical Roman Archaeology: Second Conference Proceedings, Worldwide Archaeology Series, Vol. 14, Aldershot: Avebury/Ashgate. 3-21.

Driel-Murray, C. van, 1997 'Women in forts', Jahresbericht/gesellschaft Pro Vindonissa. 55-61.

Fell, V. 1991 'Two Roman 'nit' combs from excavations at Ribchester (RBG80 and RB89), Lancashire', Ancient Monuments Laboratory Report. 87/91. http://services.english-heritage.org.uk/ResearchReportsPdfs/087-1991.pdf

Fellmann, R. 2009 Römische Kleinfunde aus Holz aus dem Legionslager Vindonissa, Brugg: Gesellschaft Pro Vindonissa.

Mumcuoglu, K.Y. and Hadas, G. 2011 'Head louse (Pediculus humanus capilis) remains in a louse comb from the Roman period excavated in the Dead Sea region', Israel Exploration Journal 61(2). 223-229.

Rackham, H. (trans.) 1968 Pliny: Natural History Vol. IV Books 12-16, Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library.

Pugsley, P. 2003 Roman Domestic Wood: Analysis of the morphology, manufacture and use of selected categories of domestic wooden artefacts with particular reference to the material from Roman Britain, British Archaeological Reports International Series 1118, Oxford: Archaeopress.

The comments facility has now been turned off.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.