Department of Archaeology, University of Chester, CH1 4BJ, UK.

Email: howard.williams@chester.ac.uk

Cite this as: Williams, H. 2016 Tressed for Death in Early Anglo-Saxon England, Internet Archaeology 42. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.42.6.7

Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, 'barbarian' communities across Britain and north-west Europe employed rich and vibrant metalwork (including cruciform, square-headed, saucer and button brooches, wrist-clasps, pendants, buckets and drinking horns) that sometimes included striking representations of humanoid heads with exaggerated beards and flowing locks. Variously interpreted as ideal representations of contemporary elites, cultic masks, legendary heroes, protective spirits, and/or pagan deities, such images remain enigmatic. Despite uncertainty over their interpretation, they might well be taken to reveal communities in which head hair - its display and transformation - were linked to important rites of passage and practices in constituting, communicating and commemorating dimensions of personhood in life and death (see Brundle 2013). However, a systematic and widespread review has yet to be written about early medieval grooming practices and hair management, fully integrating such representations with the far broader evidence for artefacts used in grooming and their archaeological contexts between the 5th and 7th centuries in southern and eastern Britain (but see Geake 1995, 143-6; Ashby 2014). Fortunately, explorations of the varying and shifting significance of grooming as both practice and metaphor in dealing with the dead have recently begun (Williams 2003; 2007; Ashby 2014).

This research field has been stifled by the persistence in regarding antler and bone combs and iron, bronze and (more rarely) silver toilet implements (including miniature items) as disparate personal items used exclusively in utilitarian 'grooming'. Conversely, calling miniature items 'amulets', while drawing attention to their potential magical properties in mortuary environments, is predicated on their presumed lack of practical utility. The term 'amulets' can obscure rather than reveal, by masking the connections between 'functioning' and 'miniature' grooming implements' and overshadowing their shared potential relationships with ritualised acts of trimming and dressing head hair in the early Anglo-Saxon mortuary process. Even in discussions of richly furnished early medieval burials in which grooming implements are included and might have been used during multiple and successive stages of theatrical death rituals leading up to their deposition with the dead, combs and toilet items are regularly perceived as subsidiary and supplementary to other artefact-groups including weapons, jewellery and feasting gear (e.g. Williams 2001; 2006; 2011a).

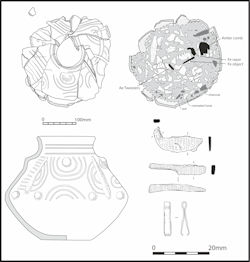

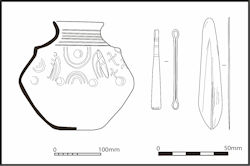

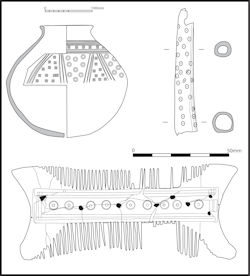

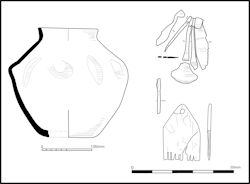

Combs, tweezers, shears, razors, and sometimes ear scoops too, can be profitably interpreted as key elements of 'technologies of remembrance': chains of operations enacted during the mortuary process and serving in the selective remembering and forgetting the dead (see Williams 2015 for an extended discussion). For 5th/early 6th-century cremation practices, these items held a special importance. Fragments of combs and toilet items and sets (some full-sized, some small and some demonstrably miniatures) were placed unburnt in a significant minority of cinerary urns after survivors had collected the ashes from the funeral pyre (Williams 2003; 2007). For example, the large cremation cemetery at Sancton, East Yorkshire, contains many examples of decorated cinerary urns accompanied not only by burnt dress accessories but also unburnt toilet implements and combs. Some items were miniatures and others were full-sized but incomplete (Timby 1993; Figures 1 and 2). A further example from a recently published excavation is the 'Minerva' mixed-rite (bi-ritual) cemetery of Alwalton, Cambridgeshire, where the majority of cinerary urns contained an unburnt fragment of an antler comb (Gibson 2007; see also Williams 2011b; 2015; Figures 3 and 4). Practices varied between cemeteries and across England in terms of the frequency and character of grooming implements' deposition with the cremated dead. Yet a distinctive use of miniature antler combs and miniature iron toilet implements/tool-kits has been identified at some southern English sites, notably Worthy Park, Kingsworthy, Hampshire and Saxton Road, Abingdon, Oxfordshire (Hawkes et al. 2003, 124-5, 130; Williams 2011b; 2015; Figure 5).

It seems that, for some early Anglo-Saxon funerals, the fiery transformation of the cadaver was accompanied by rituals linked to the cutting and dressing of hair. Following cremation, the dry, fragmented, distorted and shrunken human bone was retrieved, collected into urns, and supplemented with grooming implements. This might be interpreted as a mnemonic strategy for articulating the building of a new corporeal surface and personhood for the ashes and within the grave (Nugent and Williams 2012; Williams 2003; 2007; 2014; 2015).

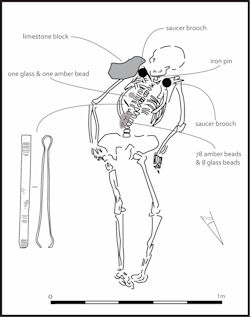

While there seems to be a special relationship between cremation and grooming implements, 5th-6th-century inhumation graves also on occasion include combs and toilet items (see Williams 2007). Such practices need consideration as deliberate acts of deposition rather than incidental elements of furnished costume. For example, sixth-century grave 75 from Watchfield (Oxfordshire) contained the supine skeleton of an adult aged 35-40 years buried with a pair of gilded cast copper-alloy saucer brooches, and a loop-headed iron pin, all situated on the clavicles (Figure 6). In addition, a single glass bead and single amber bead were placed on the right ribcage; their position suggests they had been placed on the cadaver rather than worn suspended as a festoon from the brooches. Also upon the chest were copper-alloy tweezers, perhaps originally suspended on an iron loop (Scull 1992, 188-90).

Newly published cemeteries are revealing fresh dimensions to the connection between grooming and death into the late 6th and 7th centuries AD: a time of kingdom formation and Christian conversion. At the recently published mixed-rite Tranmer House cemetery, Suffolk, grave 8 shows the inclusion of an antler comb as part of a high-status mid-late sixth-century cremation burial within a pair of touching vessels - a pot and a bronze hanging bowl. It is possible that this indicates a specific connection between combs, bowls and grooming practices in commemorating the cremated dead (Newman 2005, 486; Penn 2011, 79; Fern 2015, 44-6).

We find evidence that wealthy and 'princely' seventh-century graves, despite their variability, share the theme of hair-related rituals involving intimate acts of placing grooming implements with the dead in the final stages of funerals. While discussions have focused on the allusions to feasting and martial identity in these graves, I would argue that mnemonic acts linking to grooming served not only to negotiate the transformation of the dead, but also to install the dead as dressed and hirsute corporeal presences in the early medieval landscape beneath prominent burial mounds. For example, this theme links together both cremation and inhumation graves at the famous Sutton Hoo burial ground, Suffolk (Carver 2005, 67-9, 75, 87-96, 101-5; Evans 2005, 202-8, 210). The richly furnished Mound 17 weapon burial had a comb added in the latter stages of the burial rite (Carver 2005, 132). There were an exceptional three combs centrally positioned amidst the fabulous Mound 1 assemblage at Sutton Hoo (Bruce-Mitford 1975, 444, 474; Evans and Galloway 1983, 813-30; Carver 2005, 179-99). On the pyre and/or in the grave, these items defined the deceased's sartorial elegance and transformation from head to toe. More than of a personal significance, grooming and washing the body prompted and directed social remembrance.

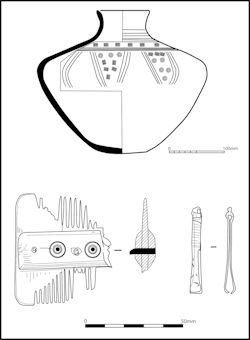

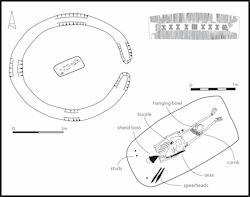

A further male-gendered example is the rich mid-seventh-century weapon burial from a primary burial mound excavated at Ford, Laverstock, Wiltshire. Here the adult male was interred with a belt buckle, 'sugar-loaf' bossed shield (with three studs surviving of the shield board), two spears (the spearheads survived) and a seax with silver fittings in its sheath. This rich collection of weapons and dress accessory have dominated interpretations of the grave as one of a class of rich barrow-burials found across the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. However, at the very centre of the grave, a strikingly well-preserved 19cm-long double-sided comb was placed on top of a bronze hanging bowl found to contain traces of vegetable material, identified as possible onion bulbs and crab apples. It remains unclear whether the bulbs and apples constitute food or some other concoction, but it might be suggested that, together, the bowl and comb were perhaps associated with sustaining and grooming for the deceased’s body; therefore, they were dimensions of social practice central not only to the deceased's personal identity but to wider bodily techniques that defined his membership of a wider social network and their masculine elite personhood (Musty 1969; Figure 7).

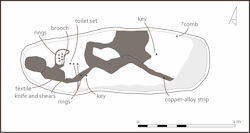

Mid-/late seventh-century wealthy female-gendered inhumation graves show this theme enduring through the Anglo-Saxon elite's Christian conversion. For example, five wealthy female-gendered inhumation graves from a seventh-century cemetery at Harford Farm, Norfolk, indicate an enduring association between death and grooming. Here, silver miniature toilet sets communicated and constituted the aristocratic (arguably Christian) identities of their bearers (Penn 2000; Williams 2006, 65-77; 2010; Figure 8). This evidence provides demonstrably secular predecessors and equivalent depositional practices involving grooming implements to the well-recognised Christian and liturgical use of combs from the seventh century, strikingly revealed in the ecclesiastical elite mortuary context by the double-sided ivory comb interred in the tomb of St Cuthbert (most recently discussed in Ashby 2014).

There remains much more research to be done to investigate grooming practices and metaphors in early Anglo-Saxon England and situate them in a broader context of late Antique/early medieval Britain, north-west Europe and Scandinavia. For the graves briefly explored here, it is argued that grooming implements might be seen as mnemonic generators rather than simply as ethnic markers or status symbols. Through their use and interment with ashes and unburnt bodies, grooming implements created and re-created specific portrayals of personhood in death. Subsequently, during a protracted period of social, political, economic and religious transformation associated with kingdom formation and Christian conversion, grooming became a central dimension of constituting and commemorating elite personhood. Being tressed for death seems to be a varied but unquestionable strand of continuity from pre-Christian to early Christian mortuary practice (Williams 2006; 2010; see also Ashby 2014).

Ashby S. 2014 'Technologies of appearance: hair behaviour in early medieval Europe', Archaeological Journal 171. 151-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2014.11078265

Bruce-Mitford, R. and Evans, A.C. 1975 The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Volume I: Excavations, Background, the Ship, Dating and Inventory. London: The British Museum.

Brundle, L. 2013 'the body on display: exploring the role and use of figurines in early Anglo-Saxon England', Journal of Social Archaeology 13(2). 197-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1469605312469455

Carver, M. 2005 Sutton Hoo: A Seventh-Century Princely Burial Ground and its Context, London: Society of Antiquaries of London.

Evans, S.C. and Galloway, P. 1983 'The combs', in R. Bruce-Mitford and A.C. Evans, The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Volume I: Excavations, Background, the Ship, Dating and Inventory, London: The British Museum. 813-32.

Evans, S.C. 2005 'Seventh-century assemblages', in M. Carver, Sutton Hoo: A Seventh-Century Princely Burial Ground and its Context, London: Society of Antiquaries of London. 201-82.

Fern, C. 2015 Before Sutton Hoo: the Prehistoric Remains and Early Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Tranmer House, Bromeswell, Suffolk, Ipswich: East Anglian Archaeology, 155.

Geake, H. 1995 The Use of Grave-Goods in Conversion-Period England c. 600-c. 850 AD, 2 volumes, York: Unpublished PhD Thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of York.

Gibson, C. 2007 'Minerva: an early Anglo-Saxon mixed-rite cemetery in Alwalton, Cambridgeshire' in S. Semple and H. Williams (eds) Early Medieval Mortuary Practices: Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 14, Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. 238-350.

Hawkes, S.C., Grainger, G., Bayley, J., Dodd, A. and Biddulph, E. 2003 The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Worthy Park, Kingsworthy, near Winchester, Hampshire, Oxford: Oxford University School of Archaeology Monograph 59.

Musty, J. 1969 'The excavation of two barrows, one of Saxon date, at Ford, Laverstock, near Salisbury, Wiltshire', Antiquaries Journal 49. 98-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500032583

Newman, J. 2005 'Survey in the Deben valley', in M. Carver, Sutton Hoo: A Seventh-Century Princely Burial Ground and its Context, London: Society of Antiquaries of London. 477-87.

Nugent, R. and Williams, H. 2012 'Sighted surfaces: ocular agency in early Anglo-Saxon cremation burials' in I-M. Back Danielsson, F. Fahlander and Y. Sjöstrand (eds) Encountering Images: Materialities, Perceptions, Relations, Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 57, Stockholm: Stockholm University. 187-208.

Penn, K. 2000 Norwich Southern Bypass, Part II: Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Harford Farm, Caistor St Edmund, East Anglian Archaeology 92, Dereham: Norfolk Museum Service.

Penn, K. 2011 The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Shrubland Hall Quarry, Coddenham, Suffolk, East Anglian Archaeology 139, Ipswich: Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service.

Scull, C. 1992 'Excavation and survey at Watchfield, Oxfordshire, 1983-92', Archaeological Journal 149. 124-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1992.11078009

Timby, J. 1993 'Sancton I Anglo-Saxon cemetery. Excavations carried out between 1976 and 1980', Archaeological Journal 150. 243-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1993.11078057

Williams, H. 2001 'Death, memory and time: a consideration of mortuary practices at Sutton Hoo' in C. Humphrey and W. Ormrod (eds) Time in the Middle Ages, Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. 35-71.

Williams, H. 2003 'Material culture as memory: combs and cremation in early medieval Britain', Early Medieval Europe 12(2). 89-128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-9462.2004.00123.x

Williams, H. 2006 Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489594

Williams, H. 2007 'Transforming body and soul: toilet implements in early Anglo-Saxon graves' in S. Semple and H. Williams (eds) Early Medieval Mortuary Practices: Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 14, Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. 66-91.

Williams, H. 2010 'Engendered bodies and objects of memory in Final Phase graves' in J. Buckberry and A. Cherryson (eds) Burial in Later Anglo-Saxon England c. 650-1100 AD, Oxford: Oxbow Books. 24-36.

Williams, H. 2011a 'The sense of being seen: ocular effects at Sutton Hoo', Journal of Social Archaeology 11(1). 99-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1469605310381034

Williams H. 2011b 'Mortuary practices in early Anglo-Saxon England' in H. Hamerow, D. Hinton and S. Crawford (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 238-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199212149.013.0014

Williams, H. 2013 'Death, memory and material culture: catalytic commemoration and the cremated dead' in S. Tarlow and L. Nilsson Stutz (eds) The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 195-208.

Williams, H. 2014 'A well-urned rest: cremation and inhumation in early Anglo-Saxon England' in I. Kuijt, C.P. Quinn and G. Cooney (eds) Transformation by Fire: The Archaeology of Cremation in Cultural Context, Tucson: University of Arizona Press. 93-118.

Williams, H. 2015 'Death, hair and memory: cremation's heterogeneity in early Anglo-Saxon England', Analecta Archaeologica Ressoviensia, 10. 29-76. http://www.archeologia.ur.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/AAR10_Williams_np.pdf

The comments facility has now been turned off.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.