Department of Historical Studies, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden.

Email: elisabeth.nordbladh@archaeology.gu.se

Cite this as: Arwill-Nordbladh, E. 2016 Viking Age Hair, Internet Archaeology 42. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.42.6.8

In a passage of Skáldskaparmál, a section of the Icelandic 13th-century Edda, Snorri Sturluson discusses different metaphors, or kennings, for gold. Concerning one of them, he asks, 'Why is gold called Siv's hair?' Then follows the narrative of how Loki, the trickster of the Old Norse pantheon, 'for love of mischief' had cut off the long golden hair of Siv, wife of the god of thunder, Thor (Clunies Ross 1994, 59). This atrocity made Thor furious. To make amends, Loki had to provide the gods with the most precious gifts, crafted and enchanted by dwarfs, who were skilled in both smith-work and magic. Siv was given a new head of hair of pure gold, which would grow on her head like natural hair (Lindow 2001, 266). Thor, who was entrusted with Siv's hair to give to her, was also given the magic hammer, Mjölnir. Odin received the magic spear Gungnir and a ring of gold that every ninth night would create eight new golden rings. Finally, Frej was given the ship Skidbladnir, and a fast running boar with golden bristles.

This episode tells us that hair was a significant and highly esteemed part of the body. Inflicting damage on Siv's hair was both a crime and an offence. Based on the frequently encountered cultural idea that access to someone's hair equates with access to the body as a whole, Margaret Clunies Ross (1994, 59-61) suggests that with this disgrace - humiliating Thor by severing this part of his wife's body - Loki also insinuated that Siv was a goddess of easy virtue. Such an insult was an issue for the Aesir community as a kin group. That the atonement resulted in the three main gods receiving their most emblematic attributes underlines the seriousness of the deed. Moreover, it demonstrates that hair was of significant social importance, both as a mediator of values and norms, and as a material item, open for physical arrangement and rearrangement.

Hair has very specific physical characteristics. It is constantly growing but is also disposed to to fall out and cause baldness. It is painless to cut but causes pain if torn. It combines fragility with a strong texture, and it is capable of being formed in various hairstyles. If physical variations like colour, texture, curliness or straightness, and the need for care are added, hair's materiality is connected with culturally required grooming techniques and grooming equipment (Ashby 2014). Moreover, a dead body's hair decays differently from flesh and bone. Tufts of hair may sometimes be preserved and tended for centuries as relics or memorabilia. Thus, the importance of hair and hair grooming is remarkable, and in many societies, hair has been considered a powerful social, symbolic, and communicative resource (Hallpike 1969). Consequently, hair articulation is not neutral but laden with 'historical, cultural, political, and gendered meanings' (Bordo 2008, 409).

In Viking-Age Scandinavia, hair also seems to have played an important role in social dynamics. Hedeager (2015, 134) reminds us that Snorri Sturluson in Skáldskaparmál considers women's and men's proper physical appearance as crucial for creating the essence of a gendered social person - including hair and its styling. Hair as a social matter is demonstrated by some passages in the Old Norse poem Rigsthula, where attention is paid to the colour of the hair, designating old age and different social classes. Choices related to the physical phenomena of hair - hair preparation, grooming and its equipment, and a desired hairstyle that influenced one's appearance - were all part of a process that Ashby (2014, 153-54) designates as hair behaviour.

The narrative of Siv's golden hair belongs to a literary corpus that was written down some two to three hundred years after the last part of the Viking Age, an era that lasted from approximately 790-1100 AD. Using these written records requires careful source criticism; however, most scholars agree that the Icelandic Sagas can be used in many ways to discuss the 'mentality, ideas, social structure, farm life, and everyday customs' of Old Norse society (Lönnroth 2008, 309). In the Sagas, the character of both women's and men's head hair is often mentioned. For men, beards and sometimes eyebrows are also facial attributes of significance (Audur Magnusdóttir, personal communication). For example, in Njal's Saga, some men were ridiculed for being beardless, thus implying an 'unmanly' and weak behaviour. For women, beautiful hair seems to have been a highly valued attribute (Magnusdóttir 2016, 120).

Continental texts from the centuries that precede the Viking Age also highlight the symbolic meaning of hair. Such examples are the importance of long hair in the Merovingian and Lombard cultures (Wallace-Hadrill 1962; Goosmann 2012; Axboe and Källström 2013), or the cutting of hair or head shaving in the creation of the religious attribute of tonsure in Early Medieval Europe, as recorded by Charlemagne's biographer Einhard in the first chapter, Capitulum Primum, of his Vita Karoli Magni from about 820 AD. It is not unlikely that continental ideas regarding the significance of hair articulation influenced people in Scandinavia, as much of the contemporary high-status Scandinavian archaeological material indicates connections with Merovingian and Carolingian spheres. Nevertheless, a specific Scandinavian hairstyle might have been a way of declaring an individual's ethnic and social position. This connection may be indicated by a passage in the early Christian Norwegian Kristenrett, from the law of Borgarthing, which states that if a drowned seafarer with a Norse hairstyle had been washed ashore, he should be buried in a Christian graveyard (Keyser and Munch 1848, 44, Ældre Borgartingslov. Vikens Kristenret, 1914, 24).

The Viking Age iconographic material provides several sources for studying human figures and appearance, including hair articulation. Within this category, the so-called picture stones offer important evidence. These raised stones, which appear on the Baltic island of Gotland and create significant places in the landscape, show a number of narrative scenes, with people sailing, horse riding, travelling in carts, fighting, or taking part in other activities (Figure 1; Nylén and Lamm 1988; Gotländskt Arkiv 2012). Both women and men appear in the scenes. In her investigation of gender and body language as expressed on the Viking Age picture stones, Eva-Marie Göransson has, among other things, analysed female and male hair styles (1999, 40-42). For women, the most common coiffure was a long ponytail, coiled into a knot close to the head, sometimes called the 'Irish ribbon knot' (Hedeager 2015, 134). Occasionally the ponytail was plain. Next in popularity was the topknot. These hairstyles were a prominent part of high-status female appearance, showing an S-curved body line with a long skirt and a solemn and controlled posture. Sometimes the body language included the inviting gesture of an outreached drinking horn. It is of course possible that this image of a 'lady of magnificence', to use Göransson's (1999) term (praktfru in Swedish), represented a fictive notion of an ideal figure, but if a real social category was represented, the treatment of these women's hair must have been part of a long-term project, as the coiled ponytail required very long hair. Growing and keeping such long hair needed attention and care for many years. This implies long term strategies regarding hair as a social and symbolic resource. (Göransson 1999, 41).

Among the men, the majority of the pictures showed them with short hair. However, about one-third of her sample wore their hair in a plait. An even more pronounced trait was the beard. Göransson could also distinguish some that she labelled androgynous, with both beards and female dress, and even one bearded figure with a ponytail.

The women and men on the picture stones showed narratives or activities that were connected to the rules and norms of body language including gestures, postures, costumes, and coiffures. Even if the figures themselves were miniaturised, their abundance and placement on these large stones demonstrated the ideals of dress and hair behaviour on a grand scale in the landscape. A similar mode of appearance can be seen on some rare fragments of textile, such as the tapestry fragments from Överhogdal in Sweden and Rolvsøy and Oseberg in Norway. Processions of walking people and horses with wagons seem to connect the textiles and the picture stones to the same norms in terms of appearance. Where discernible, the most pronounced female hairstyle is the coiled ponytail. This style is also shown on some of the horses' tails (Christensen et al. 1992, 233-34), possibly attributing feminine features to the horses. With regards to Oseberg and Rolvsøy, the textiles with their various meanings, including concepts of bodily appearance, were found as parts of the furnished burial chamber, connecting these ideas of new material realities with the afterlife (Arwill-Nordbladh 1998, 242-50; Vedeler 2014). However, it is most likely that such tapestries were also used as decorations in houses, shown for selected groups of people in halls, or hung in other rooms for festivities. In this way, acceptable modes of decorum for a certain social segment were conveyed (Arwill-Nordbladh 1998, 159-60).

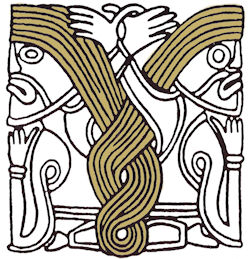

Another category of imagery featuring human beings appears on the small, stamped gold foils often called guldgubbar. On specific sites, these can be found in abundance and many thousands have been found in total. The majority have been dated to the 6th-8th centuries, but they still appear in the Viking Age. These guldgubbar have been discovered inside large buildings or great halls that would have belonged to magnates, but they are also found in the open landscape (for an overview, see Watt 1999). In most cases, men are depicted. Their hairstyles vary from short to shoulder-length, sometimes even curled. Occasionally, however, the hair is hidden by a cap or other headgear. The women's hairstyle is less varied: the coiled-knot ponytail dominates (Figure 2). For the men, a moustache also features (see, for example, Ashby 2014, 174; Hedeager 2014, 285-86). The images on the guldgubbar and the picture stones suggest that women's hair was styled in a similar way over a period of about 500 years. In contrast, the hair articulation of men was more varied. This differing male hairstyle is underlined by another type of evidence, the gold bracteates. They were produced from the middle of the 5th century AD and into the early 6th century, thus contemporary with the earliest guldgubbar. Many of them depict men, and their head profiles may show short hair, hair styled as a ridge, or long hair ending with a curl at the neck. In addition, an en face image showing the long hair framing both sides of the face in a pigtail-like style also occurs (Figure 3; Axboe and Källström 2013).

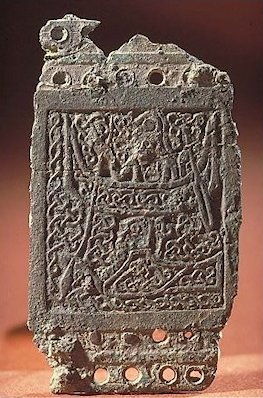

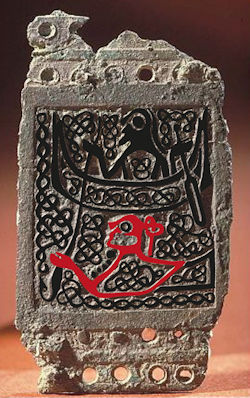

A significant piece of evidence of hair articulation, which highlights the presence of men's long hair, appears on a small piece of gold mounting from the sword of the Norwegian Migration-period grave in Snartemo (Figure 4; Magnus 2003). In this case, the long hair of two men, depicted kneeling back to back, is coiled and linked together, fastening the men to each other as if their two bodies shared the same long hair. This is one of many instances where the hairstyle is integrated into the ornamental curves of metal objects. As late Iron Age Scandinavian art is distinguished by a horror vacui animal style curvature, the hair articulation often blends with other body parts of men or animals like a picture puzzle (Hedeager 2004; Kristoffersen 2010). Thus, there are many examples of faces and masks with hairstyles in the Scandinavian ornamental style in the late Iron Age, including the Viking Age (Helmbrecht 2011). However, these varied coiffures may not necessarily have been used on a daily basis, as many scholars believe that the imagery expresses mythical or ancestral beliefs (for example, Magnus 2003; Kristoffersen 2010; Hedeager 2011). Nevertheless, even if the hairstyles displayed on these items may have been imaginary, they bear witness to the fact that such appearances were part of the accepted notions of hair articulation.

The images discussed above were designed to be meaningful patterns in the decoration of objects such as brooches, mountings, and the like. Even if they were small and their intricate compositions were most likely difficult to discern, they must have been objects of power for their users. Being displayed in performative events, the images confirmed notions or norms regarding corporeal behaviour, including hair articulation. These small images reinforce the impression given from the picture stones that the masculine hair articulation was more varied than the feminine during the late Iron Age. A bronze mount dated to the 7th or 8th century from a cremation grave in Solberga, Östergötland, Sweden (Figure 5a-5b) can serve as a chronological link in this approximately 20 generations-long chain. In this image, a man is sitting in a boat fishing and wearing headgear that reaches down to his shoulders and might also be interpreted as hair. Under the boat a woman is swimming, reaching for the hook - for us an unknown, maybe mythical, person who is connected to the sea. The woman's hair has been gathered into a ponytail and then coiled into an 'Irish knot', thus signifying affinity with the earlier images showing this coiffure and serving as a link to later ones.

A distinctive feature of Viking Age material culture was the presence of miniatures, serving as amulets, decorations on clothing, or used for other purposes (Gräslund 2008; Jensen 2010). Some of these small-scale objects show human figures. Burial and settlement sites such as Birka, Uppåkra, Lejre, and Tissø are examples of high-status contexts in which such finds appear. The use of precious materials such as bronze or other copper alloys, or silver that was sometimes gilded or foiled with gold, underscores that this was a high ranked milieu. The hairstyles and headgear depicted on these miniatures emphasises the interpretation that masculine hair articulation was more varied and included different headgear, while feminine hairstyles were restricted to the ponytail and topknot. However, new finds constantly widen the social roles that can be associated with this feminine hairstyle. Not only the 'lady of magnificence' or other high-status women, or women and other creatures with mythical connotations, were associated with the coiled ponytail. Recently, a little silver figurine of a woman (Figures 6 and 7) equipped with a shield and a sword, 'The Valkyrie from Hårby', demonstrated that women were allowed to combine the traditional long dress and hair custom with martial equipment (see for example Price 2015, 5-7). Very occasionally, as shown on the little figurine called 'Odin from Lejre', gender neutral headgear could appear, which together with the other attributes featured on this miniature, could convey a gender ambiguous character (Back Danielsson 2010; Arwill-Nordbladh 2013), an ambiguity that is discernible elsewhere (Back Danielsson 2014).

There is, however, a small group of objects that show a quite different female hair articulation. In Denmark, a gilded silver figure from Tissø, a bronze figure from Stavsanger and most recently, a find of a copper-alloy figure from Stålmosegård all show a female figure wearing a long dress and probably jewellery, with her hair combed in two pretzel or pigtail-like arrangements. The body language is peculiar, as it seems that she is tearing at her hair. This coiffure, sometimes without the tearing gesture, appears on a few more items from other sites (Helmbrecht 2011, 156 abb. 56; Arwill-Nordbladh 2012, 46-47; Kastholm 2015, compare the picture stone from Smiss), and it occasionally merges into the contemporary animal art style. Kastholm (2015) pays attention to the Stålmosegård figurine's unusual facial expression in combination with the hair tearing, and suggests that the little object depicts the ecstatic state of a shamanistic performance. For the Tissø figure, it has been suggested that its odd, ocular expression may signify a prophetic seeress (Arwill-Nordbladh 2012). However faint the evidence may be, these images may indicate that hair being gathered together and coiled to form a firm knot articulated a more restrained and self-controlled code of conduct than hair that was arranged to turn outwards from the head, sometimes even torn (compare Leach 1958, 154).

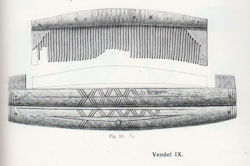

Some of the most common objects found in Iron Age burials and some settlement sites are combs and traces of comb production. In Scandinavia, combs are present in many prehistoric contexts, but they appear more frequently from the early Iron Age and all through the Iron Age era. Most of them are made from bone or antler (for example Ambrosiani 1981). Their form and decoration have been used to establish typological and chronological sequences. The archaeological record proves that both men and women possessed them, and many scholars believe that combs were personal belongings. Both women and men could carry a comb in their belts; this was sometimes placed in a cover of bone and sometimes in a case or purse, usually of leather (Figure 8). It is likely that their regular use and their close connection to an individual's potent and significant body part (i.e. the hair), could lend a particular kind of affinity to combs. This connection could explain why combs are so frequent in graves. It is possible that the prevalent belief indicated that it would be unwise for anyone else to use a dead person's combs.

The shape and ornamentation of some combs show a remarkable resemblance to Viking Age halls, and Terje Gansum (2003) has suggested that these combs were loaded with symbolic significance as the hall was a centre for activities that constituted the foundation of Iron Age social order in terms of rank.

For men, in addition to grooming their hair, a well-groomed beard might also have been important, signifying rank and status. It is seemingly noteworthy that the nicknames of two of the most renowned Viking leaders, Svein Forkbeard and Harald the Fairhair, referred to their hair. It is possible that beard grooming procedures or parts thereof were carried out by the bearded person himself, but it is also plausible that a second person could assist with washing, shaving, cutting, combing, and braiding. In comparison with combs, late Iron Age finds of razors are not so abundant; however, a knife could serve the same purpose.

Viking Age grooming could include additional practices other than just tending head-hair and beard. Some women's graves contain a small implement, which has often been interpreted as an ear spoon, used as an ear cleaner. The woman in Birka grave 507 was equipped with such a tool (Figure 9). Made of silver, and partially gilded, one side of its oval handle was decorated to show a lady with her hair styled in the traditional coiled ponytail, holding a horn in her outstretched hand. Both the context of the grave and the decoration of the ear spoon, implies that this kind of body care is linked to the female high-status domain (Gräslund 1989).

In Iron Age Scandinavia there exist a few grave-finds with tufts of human hair that have been detached from the body - either from the dead subject or from a living participant in the funerary event (see Lund and Arwill-Nordbladh 2016). In each of these burials the hair had been treated as a special object and kept separate from the body. In an inhumation grave from Kvinesdal, Norway, dated to the 5th century AD, the corpse was placed in a stone cist together with some grave goods (Solberg 1993; Gansum 2003, 202). On a slab at the lower end of the cist a folded tuft of hair was placed. Over time the corpse decayed and today only the hair remains. Another specimen of hair, from the East Mound in Uppsala, now probably lost, is known from written reports (Lindqvist 1936, 138). Here a tuft of hair was placed at the bottom of the mound, clearly separated from the cremated bones of two individuals. A third example comes from the cremation burial of Skopintull on the island of Adelsö in Lake Mälaren (Figure 10; Rydh 1936, 104-28). Here a long piece of cut hair was placed at the bottom of a bronze bucket, which was subsequently filled with a selection of cremated bones of two human beings, animals and some small objects.

These three cases indicate that the hair, after being separated from the body was treated as a very special physical phenomenon. Anthropological observations offer many examples of ritual behaviour, in particular during processes of rites des passages, where hair and hair treatment constituted meaningful parts. If separated from the body, the cut off hair, as a transitional object parted from its former identity, would often be understood as a powerful and potent item, in the words of Edmund Leach (1958) characterised as 'a magic object'.

The archaeological record shows that people in late Iron Age Scandinavia lived in a vibrant era. Active and forceful identity groups like kin and families, local and regional groups of leaders, communities of gender, ranks, and practitioners of religious rites, were some of the many interacting factions. Significant in such processes were practices related to the body, including hair and its treatment. Such phenomena dominate the archaeological record, and as a result this brief overview of hair behaviour may be biased towards high-status groups and their social situations, connected to rituals and ceremonies. In this context, however, one can conclude that both women's and men's hair articulation was a significant social and cultural feature. Throughout the centuries, men were shown carrying out more varied activities than women, thus demonstrating a wider range of corporeal differentiations, including head hair and beard styling. We can thus conclude that men had access to a more varied palette regarding hair behaviour. Regarding female hair articulations, one hairstyle — the coiled and knot ponytail — maintained its importance for many centuries, indicating that there existed norms, techniques and practices to retain this gendered memory for generations. For both women and men, hair and its articulations seems to have been an important feature, expressing social norms and roles, but also exceptional status. With its specific material character, hair was an indispensable and creative part in social dynamics.

My warm thanks to Auður Magnusdóttir for sharing her knowledge of the Edda texts, and to Henrik Alexandersson for useful information of the Borgarting Law. I also wish to thank Bente Magnus, who has kindly given access to the illustration in Figure 4, to Richard Potter for picture processing and to Sara Ellis Nilsson for revising the English in earlier drafts.

Ældre Borgartingslov. Vikens Kristenret, 1914. Kristiania.

Ambrosiani, K. 1981 Viking Age Combs, Comb making and Comb makers in the light of finds from Birka and Ribe, Stockholm studies in archaeology 2. Stockholm: Institutionen för arkeologi, Stockholms Universitet.

Arwill-Nordbladh, E. 1998 Genuskonstruktioner i Nordisk Vikingatid. Förr och nu, Gothenburg Archaeological Theses, Series B9, Göteborg: Institutionen för arkeologi, Göteborgs Universitet.

Arwill-Nordbladh, E. 2012 'Ability and disability: on bodily variations and bodily possibilities in Viking Age myth and image', in I.M. Back Danielsson, and S. Thedéen (eds), To Tender Gender. The pasts and futures of gender research in archaeology, Stockholm: Stockholms Universitet. 33-59.

Arwill-Nordbladh, E. 2013 'Negotiating normativities: 'Odin from Lejre' as challenger of hegemonic orders', Journal of Danish Archaeology 2(1). 87-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21662282.2013.791131

Ashby, S.P. 2014 'Technologies of appearance: hair behaviour in Early-Medieval Britain and Europe', Archaeological Journal 171. 153-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2014.11078265

Axboe, M. and Källström, M. 2013 'Guldbrakteater fra Trollhättn 1844-2009', Fornvännen 108. 153-171.

Back Danielsson, I.M. 2010 'Liten lurifax i Lejre', Arkaeologisk Forum 22. 30-33.

Back Danielsson, I.M. 2014 'Handlingar på gränsen: En hypotes kring hetero- och homoerotiska uttryck heliga Helgö och närliggande Hundhamra under yngre järnålder', in H. Alexandersson, A. Andreeff and A. Bünz (eds), Med hjärta och hjärna: En vänbok till professor Elisabeth Arwill-Nordbladh, Gothenburg: Department of Historical Studies, University of Gothenburg. 259-275.

Bordo, S. 2008 'Cassie's hair', in S. Alaimo and S. Hekman (eds), Material Feminisms, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 400-424.

Christensen, A.E., Ingstad, A.-S. and Myhre, B. 1992 Osebergdronningens grav, Oslo: Schibsted.

Clunies Ross, M. 1994 'Þórrs honour', in H. Uecker (ed) Studien zum Altgermanischen: Festschrift für Heinrich Beck, Berlin: de Gruyter. 48-76.

Gansum, T. 2003 'Hår og stil og stiligt år. Om långhåret maktsymbolikk', in P. Rolfsen and F.-A. Stylegar (eds), Snartemofunnene i nytt lys, Oslo: Universitets kulturhistoriska museer, Universitet i Oslo. 191-221.

Goosmann, E. 2012 'The long-haired kings of the Franks: 'like so many Samsons?'' Early Medieval Europe 22(3). 233-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0254.2012.00343.x

Gotländskt Arkiv 2012 Gotland's Picture Stones. Bearers of an enigmatic legacy, Visby: Fornsalen Publishing, Gotlands Museum.

Gräslund, A.-S. 1989 ''Gud hjälpe nu väl hennes själ'. Om runstenskvinnorna, deras roll vid kristnandet och deras plats i familj och samhälle', Tor 22. 223-244.

Gräslund, A-S. 2008 'The material culture of Old Norse religion', in S. Brinck and N. Price (eds), The Viking World, Abingdon: Routledge. 249-256.

Göransson, E.M. 1999 Bilder av kvinnor och kvinnlighet. Genus och kroppspråk under övergången till kristendomen, Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 18, Stockholm: Arkeologiska institutionen, Stockolms Universitet.

Hallpike, C.R. 1969 'Social hair', Man, New Series 4(2). 256-264.

Hedeager, L. 2004 'Dyr og andre mennesker - mennesker og andre dyr. Dyreornamentikkens transcendentala realitet', in A. Andrén, K. Jennbert and C. Raudcere (eds), Ordning mot Kaos, Lund: Nordic Academic Press. 219-252.

Hedeager, L. 2011 Iron Age Myth and Materiality: an archaeology of Scandinavia, AD 400-1000, London: Routledge.

Hedeager, L. 2014 'Gender on display: scrutinizing the gold foil figures', in H. Alexandersson, A. Andreeff and A. Bünz (eds), Med hjärta och hjärna: En vänbok till professor Elisabeth Arwill-Nordbladh, Gothenburg: Department of Historical Studies, University of Gothenburg. 277-93.

Hedeager, L. 2015 'For the blind eye only? Scandinavian gold foils and the power of small things', Norwegian Archaeological Review, 48(2). 129-151. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2015.1104516

Helmbrecht, M. 2011 Wirkmächtige Kommunikationsgeräten. Menschenbilder der Vendel-und Wikingerzeit und ihre Kontexte. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia Series Prima in 4. Lunds Universitet: Lund.

Jensen, B. 2010 Viking Age Amulets in Scandinavia and Western Europe, British Archaeological Report International Series S2169, Oxford: BAR.

Kastholm, O.T. 2015 'En hårriver fra vikingetiden - Nyt fra udgraveningnerne i Vindinge'. ROMU 2014. 76-94.

Keyser, R. and Munch, P.A. (eds) 1848 Norges gamle love indtil 1387, Bd1, 1:9. Christiania.

Kristoffersen, S. 2010 'Half beast - half man. Hybrid figures in animal art', World Archaeology 42(2). 216-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00438241003672906

Leach, E. 1958 'Magic hair', The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 88(2). 47-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2844249

Lindqvist, S. 1936 Uppsala högar och Ottarshögen, Stockholm: Wahlström and Widstrand.

Lindow, J. 2001 Handbook of Norse Mythology, Oxford: ABC-CLIO.

Lönnroth, L. 2008 'The Icelandic sagas', in S. Brinck and N. Price (eds), The Viking World, Abingdon: Routledge. 304-310.

Lund, J. and Arwill-Nordbladh, E. 2016 'Diverging ways of relating to the past in the Viking Age' in H. Williams (ed) European Journal of Archaeology, Special Issue: Mortuary Citations: Death and Memory in the Viking World, 19:3. 415-438.

Magnus, B. 2003 'Krigerens insignier. En paraphrase over gravene II og IV fra Snartemi I Vest-Agder', in P. Rolfsen and F.-A. Stylegar (eds), Snartemofunnene i nytt lys. Oslo: Universitets kulturhistoriska museer, Universitet i Oslo. 33-52.

Magnusdóttir, A. 2016 'Förövare och offer. Kvinnor män och våld i det medeltida Island', in L. Hermansson and A. Magnusdóttir (eds), Medeltidens genus. Kvinnors och mäns roler inom kultur, rätt och smhälle. Norden och Europa ca 300-1500, Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. 111-43.

Nylén, E. and Lamm, J.P. 1988 Stones, Ships and Symbols: the picture stones of Gotland from the Viking Age and before, Hedemora: Gidlunds.

Price, N. 2015 'From Ginnungagap to the Ragnarök. Archaeologies of the Viking World', in M. Hem Eriksen, U. Pedersen, B. Rundberget, I. Axelsen and H. Lund Berg (eds), Viking Worlds. Things, Spaces and Movement, Oxford: Oxbow Books. 1-10.

Rydh, H. 1936 Förhistoriska undersökningar på Adelsö, Stockholm: Kungl. vitterhets- historie och antikvitetsakademien.

Solberg, B. 1993 'En 'hårflette' fra Kvinesdal', Arkeo 1. 29-30.

Stolpe, H.J. and Arne, T.J. 1912 Graffältet vid Vendel. Stockholm: Kungl. vitterhets- historie och antikvitetsakademien.

Vedeler, M. 2014 'The textile interior in the Oseberg burial chamber', in S. Bergerbrandt and S.H. Fossøy (eds), A Stitch in Time: Essays in Honour of Lise Bender Jørgensen. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg. 281-300.

Watt, M. 1999 'Kings or gods. Iconographic evidence from Scandinavian gold foil figures', in T.M. Dickinson and D. Griffiths (eds), The Making of Kingdoms. Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 10. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. 175-183.

Wallace-Hadrill, J.M. 1962 The Long-Haired Kings and Other Studies in Frankish History, London: Methuen.

The comments facility has now been turned off.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.