Cite this as: West, E., Christie, C., Moretti, D, Scholma-Mason, O. and Smith, A. 2024 A Route Well Travelled. The Archaeology of the A14 Huntingdon to Cambridge Road Improvement Scheme, Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.22

The route of the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon Road Improvement Scheme provides a spatial and chronological slice through the landscape affording a rare opportunity to explore the diversity and density of earlier prehistoric activity (Fig. 2.1). The archaeology of the A14 begins in the lower Palaeolithic with the Pleistocene river terrace deposits, investigated to the south of Fenstanton Gravels, containing vertebrate remains associated with a small assemblage of lithics of this date (Boismier 2021; Boismier et al. 2021; Boismier 2024). Mesolithic to Bronze Age activity was identified to varying degrees, from composite arrays of features, including significant monumental complexes and cremation cemeteries, to residual material (Table 2.1). The distribution of evidence is not uniform, with Mesolithic activity focused along the western reaches of the River Great Ouse within the landscape blocks of Brampton West, West of Ouse and River Great Ouse. Neolithic occupation evidence was scarce, with scattered features and lithics recovered from across the scheme with concentrated activity identified at Conington. The scarcity of earlier prehistoric settlement evidence is in contrast to the diversity of monuments and ceremonial complexes developing during the Neolithic and Bronze Age. The monuments of the A14 include a henge, ring-ditches, a timber circle and barrows. The emergence of burial monuments and their continued significance throughout the Bronze Age is exemplified by the middle Bronze Age cremation cemetery at the West of Ouse barrow. Detailed examination, including osteological and Bayesian analysis, of the exceptionally large cremation cemeteries uncovered at West of Ouse and Fenstanton Gravels offers insights into both populations and practices. The identification and chronological distinction of rare Bronze Age settled landscapes provide a firmer foundation for exploring the rapid expansion of settlement in the Iron Age presented in Chapter 3.

Use top bar to navigate between chapters

| Landscape Block | Period | Occupation Features/Evidence | Monuments | Burials | Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alconbury | Mesolithic | Worked flint assemblage | Pullen 2024 | ||

| Neolithic | Monument 1 | ||||

| Late Bronze Age-early Iron Age | Pit | Inhumation Burial 5.276 | |||

| Brampton West | Mesolithic | Worked flint assemblage | West et al. 2024 | ||

| Early Neolithic | Pits | ||||

| Later Neolithic | Occupation Deposit; Ditch; Pits | ||||

| Late Neolithic-early Bronze Age | Ditch; Post-hole | ||||

| Early Bronze Age | Pits; Structure | Ring-ditch 10.433 | Cemetery 103 Cemetery 200 | ||

| Early-middle Bronze Age | Monument 200 | Inhumation Burial 12.7 Inhumation Burial 12.9 | |||

| Middle Bronze Age | Ditches; Pits | Cemetery 202 Cremation Burial 12.234 | |||

| Middle-Late Bronze Age | Cremation Burial 7BC.99 Cremation Burial 7BC.73 Cremation Burial 7BC.127 | ||||

| Late Bronze Age-early Iron Age | Pits | ||||

| Brampton South | Mesolithic | Worked flint assemblage | McGalliard and Gaunt 2024 | ||

| Late Bronze Age - early Iron Age | Pit Alignment | ||||

| West of Ouse | Mesolithic | Worked flint assemblage | Christie 2024 | ||

| Neolithic | Tree throws; Pits; Ditch | Monument 1 | |||

| Early Neolithic | Pits | ||||

| Early Bronze Age | Monument 2 | Cemetery 1 | |||

| Middle Bronze Age | Cemetery 2 | ||||

| Late Bronze Age-early Iron Age | Pit Alignment | ||||

| River Great Ouse | Mesolithic | Worked flint assemblage | Atkins and Douthwaite 2024 | ||

| Early Neolithic | Pits | ||||

| Later Neolithic | Peat Deposits; Buried soil | ||||

| Early Bronze Age | Monument 1 | ||||

| Fenstanton Gravels | Mesolithic | Worked flint assemblage | Atkins 2024 | ||

| Early Neolithic | Tree throw; Pit | ||||

| Late Neolithic-early Bronze Age | Pits | ||||

| Bronze Age | Pits | Inhumation Burial 27.9 | |||

| Early Bronze Age | Tree throws; Pits | Inhumation Burial 28.505 | |||

| Middle Bronze Age | Pits; wells; waterhole | Cemetery 1 Cemetery 3 Cremation Burial 29.13 Cremation Burial 29.14 | |||

| Conington | Mesolithic | Worked flint assemblage | White et al. 2024 | ||

| Early-Middle Neolithic | Pits; Artefact Scatter; Tree throw | ||||

| Bronze Age | Monuments 1-3 | ||||

| Early Bronze Age | Enclosures; pits | ||||

| Middle Bronze Age | Enclosures; wells; pits | ||||

| Middle-Late Bronze Age | Field system; cattle burials | ||||

| Bar Hill | Prehistoric | Worked flint; residual artefacts | Scholma-Mason 2024 |

This chapter is presented chronologically, opening with an examination of the limited evidence for Mesolithic activity. This is followed by a consideration of the nature of settlement in the Neolithic and the emergence of monuments. The scale of the A14 excavations has offered an excellent opportunity to consider activity at a landscape level with a detailed overview of the evidence for Bronze Age settlement, monumental and funerary activity provided. The aim of this chapter is to present a synthetic overview of inhabitation along the A14, with wider contextualisation and consideration of the Bronze Age landscapes revealed presented in the print monograph (Christie forthcoming).

During the Mesolithic (10,000-4000 BC) the River Great Ouse flowed through a changing landscape, with climatic shifts prompting the expansion of woodland across the once open grassland (Scaife 2000, 19-20; Wiltshire 1997). The Mesolithic worked flint assemblage from the A14 excavations totalled 1685 lithics comprising cores and a wide range of tools with debitage from blade production recovered from all landscape blocks (Devaney 2024i; Table 2.2). The identification of Mesolithic activity across the A14 was not uniform, with higher concentrations of flint recovered from landscape blocks located along the gravel river terraces namely Brampton West, West of Ouse and River Great Ouse (Fig. 2.2; Devaney 2024a-i). This matches the distribution noted during the earlier A14 investigations, with fieldwalking conducted in 2009 revealing evidence of Mesolithic/early Neolithic activity primarily on the gravel terraces (Anderson et al. 2009). A greater range of cores were recovered from Brampton West, West of Ouse and River Great Ouse showing varying levels of working from fully utilised to partial working with retained cortex (Devaney 2024c-e; 2024i). A small number of backed bladelets associated with microlith production were also recovered from West of Ouse (Devaney 2024i). The tools, comprising blades, microliths and scrapers, indicate use on diverse tasks including hunting, food preparation and those involving cutting, piercing and scraping, such as hide working. While the assemblages are comparable, the higher concentration of lithics at West of Ouse, Brampton West, River Great Ouse, and Conington potentially indicates longer term activity rather than sporadic or temporary visitations (Devaney 2024i; Butler 2005, 115-16). No cut features, hearths or deposits of Mesolithic date were identified, with the lithics largely recovered from later features. In addition, the dearth of animal bone and plant remains confidently assigned to the Mesolithic means all interpretations rely solely on the flint assemblage. The chronological limits and mixing of the assemblage only allows us to discuss a 'Mesolithic population' in the broadest chronological terms, although a small number of chronologically diagnostic microliths were identified, including earlier Mesolithic examples found exclusively at West of Ouse potentially indicating an early focus of activity. The comparative analysis of the flint assemblage from across the scheme provides some insights into the development of preferred and persistent places (Devaney 2024i).

| Flint type | Alconbury | Brampton West | Brampton South | West of Ouse | River Great Ouse | Fenstanton Gravels | Conington | Bar Hill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blade | 10 | 132 | - | 97 | 47 | 8 | 36 | 5 |

| Bladelet | 11 | 251 | 4 | 156 | 84 | 28 | 63 | 2 |

| Blade-like flake | 22 | 238 | 3 | 165 | 92 | 41 | 107 | 2 |

| Single platform blade core | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Bipolar (opposed platform) blade core | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Other blade core | - | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | - |

| Bladelet core with one platform | - | 8 | - | 11 | 2 | - | 5 | - |

| Bladelet core with opposed platforms | - | 3 | - | 7 | 2 | - | - | - |

| Other bladelet core | 1 | 9 | - | 4 | - | - | - | - |

| Microlith | - | 8 | - | 8 | - | - | - | - |

| Backed bladelet | - | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 44 | 651 | 7 | 455 | 230 | 78 | 211 | 9 |

| Excavated Area (ha) | 7.20 | 78 | 5.83 | 20 | 19.82 | 55.8 | 21.4 | 23.35 |

| Relative Density (per ha) | 6.11 | 8.35 | 1.20 | 22.75 | 11.60 | 1.40 | 9.9 | 0.39 |

The differential or favoured occupation of specific topographic and environmental contexts throughout early prehistory is well established (see Billington 2016a; 2021a and Evans et al. 2016). Mesolithic evidence in the wider environs of the A14 ranges from single find spots noted in the Cambridgeshire HER, to small lithic assemblages and more substantial scatters, highlighting the diversity of Mesolithic signatures and their interpretations (Fig. 2.3). Towards the west of the scheme, several finds include a Mesolithic axe fragment uncovered at Watersmeet, Huntingdon (Nicholson 2004), and small assemblages such as at Brampton Hut (Slater 2016; MCB19582) and the A14/A604 Junction, Godmanchester (Holgate 1991, 43; Wait 1992, 81; MCB16075). At a comparable scale to the A14 and to its east, fieldwalking at Striplands Farm, Longstanton, recovered a low-density chronologically mixed assemblage that included late Mesolithic-early Neolithic material, characteristic of discarded flint-working waste and likely representing sporadic or seasonal activity (Evans and Mackay 2004). Substantial assemblages were also uncovered at Slate Hall Farm and Godwin Ridge, Over (Gerrard 1989; Evans and Vander Linden 2008). The large Mesolithic flint assemblage from Godwin Ridge, Over, paints a varied pattern of activity duration and character with all stages of the chaîne opératoire represented (Evans and Vander Linden 2008, 51; Billington 2016c). The landscape surrounding the A14 therefore displays evidence of both fleeting and more sustained Mesolithic activity with concentrations at seemingly preferred locations, such as along ridges and river crossings. These flint assemblages likely resulted from repeated visitations, potentially encompassing a diverse range of interactions, practices, and occupational patterns.

The identification of 'persistent places' in the Mesolithic has become a key research theme, with the term encompassing both functional and social factors for the seemingly long-term importance of certain locations (Barton et al. 1995; Evans et al. 2016; Billington 2016a; 2016c). The importance of specific locations, established in the Mesolithic, in some instances continued to hold significance into the Neolithic and Bronze Age. At a site scale this pattern can most clearly be identified at West of Ouse, where higher concentrations of lithics, including from the Mesolithic, were recovered from TEA 16, the area closest to the river. This area became the focus of subsequent Neolithic and Bronze Age activity with the development of West of Ouse Monuments 1 and 2. The presence of single-period assemblages, such as the exceptional later Mesolithic assemblage comprising 22,128 worked and burnt flints from Bartlow Road, Linton (Billington 2021b, 75), is rare, with many being chronologically mixed. The assemblages from the A14 contained lithics dating from the Mesolithic to the early Bronze Age, indicating long histories of human activity (Devaney 2024i). While general observations can be made based on the evidence from the A14 it is important to keep in mind that the totality of the evidence, reliant on a single material type, represents over 5000 years of human history. This presents challenges in establishing the nuances of chronological and cultural change, particularly moving from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic.

The transition to the Neolithic is often difficult to define owing to the paucity of features and the difficulty of distinguishing between late Mesolithic and early Neolithic flint industries (Evans and Vander Linden 2008; Devaney 2024i; Fig. 2.4). This is further complicated by issues surrounding the conceptualisation, understanding and identification of distinctly 'Neolithic' lifeways, particularly in the earliest Neolithic (Thomas 1999; 2007, 428). The advent of the early Neolithic in Cambridgeshire is marked by the construction of causewayed enclosures from around 3700 cal BC, such as at Etton near Peterborough, representing a significant shift in cultural, social and economic aspects of inhabitation (Whittle et al. 2011, 324-5; Last et al. 2022; White et al. 2024).

| Landscape Block | Period | Features | Number of Pits | Number of Artefact Scatters | Pottery Summary | Analysed Pottery (no. sherds) | Analysed Pottery (g) | Flint Summary | Worked Flint from Neolithic Features (Quant) | Other Finds | Animal Bone Summary | Palaeobotanical Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alconbury | Neolithic | Monument 1 | Plain bowl; Beaker; Collared Urn; Barrel Urn; Deverel Rimbury | 77* | 250* | Worked flint including flakes and blades | 81 | Cattle; sheep; dog; deer; cod | Small number of plant remains; indeterminate glume wheat grains; hazelnut shell | |||

| Brampton West | Early Neolithic | Pits | 2 | Plain Bowl | 8 | 15 | Charred cereal crops, waterlogged stems, wood and weed seeds | |||||

| Later Neolithic | Occupation deposit; Ditch; Pits | 3 | Grooved Ware | 234 | 2353 | Cores and tools including blades, an unfinished arrowhead (F73277 ), scrapers and knifes | 30 | Butchered cattle and ovicaprid-sized long bone and rib fragments | ||||

| West of Ouse | Neolithic | Tree throws; Pits; Ditch; Monument 1 | 6 | Worked flint including a high proportion of blades, a core and scrapers | 58 | Charred seeds, nutshell, parencyma and culm nodes and mineralised seed | ||||||

| Early Neolithic | Pit | 1 | Undecorated shell- and flint-tempered | 44 | 192 | Bladelets | 3 | Red Deer antler with skull attached | ||||

| River Great Ouse | Early Neolithic | Pits | 2 | Flint-tempered; plain bowl | 41 | 137 | Worked flint including. flakes, bladelets | 38 | Medium-sized mammal bone | |||

| Later Neolithic | Peat deposits; Buried soil | 1 | Worked flint including flakes, bladelets, two end scrapers and a burin | 84 | ||||||||

| Fenstanton Gravels | Early Neolithic | Tree throw; Pit | 1 | Worked flint including a high proportion of blades | 63 | |||||||

| Conington | Early-Middle Neolithic | Pits; Artefact scatter; Tree throw | 17 | 3 | Plain bowl; Mildenhall Ware; Peterborough Ware | 390 | 2538 | Worked flint; Langdale stone axe (F32495 ) | 99 | Saddle quern fragment (F32897 ) | Sheep/goat; medium-sized mammal; large mammal | Barley (Hordeum vulgare); hulled wheat (Triticum dicoccum/spelta); fragments of hazelnut shells (Corylus avellana) |

The evidence from the A14 has offered the opportunity to explore and trace continuity and change in activity patterns from the earliest to latest Neolithic (Table 2.3). The discussion is divided into the earlier (4000-2900 BC) and later Neolithic (2900-2000 BC), as a distinctly middle Neolithic signature is hard to identify. The lithic assemblage included a limited number of chronologically diagnostic tools including earlier Neolithic leaf-shaped arrowheads and later Neolithic chisel and oblique arrowheads commonly associated with Grooved Ware pottery (Devaney 2024i). The middle Neolithic was represented in the ceramic assemblage by only 106 sherds of Peterborough Ware, 103 of which were recovered from Conington (Percival 2024g). The pits and artefact scatters at Conington represent the greatest concentration of earlier Neolithic occupation evidence with scattered features and residual finds identified across the scheme. Later Neolithic evidence was concentrated towards the western end of the scheme with pits, associated with palaeochannels, uncovered at Brampton West and River Great Ouse (Table 2.3). Adjacent to the River Great Ouse is also where we see the emergence of monuments that would develop throughout the later Neolithic-earlier Bronze Age.

The earlier Neolithic activity of the A14 appears to have been highly mobile. Evidence of transient settlement and associated activity is represented by a range of features, including artefact scatters, stray finds, pits and utilised tree-throws (Table 2.3). A particularly evocative picture of this activity is painted by the contents of a single pit excavated at West of Ouse (TEA 16). Pit 160018, located at the edge of the gravel ridge overlooking the river Great Ouse, contained an assemblage of early Neolithic flint, pottery, and antler in the very early stages of working. The antler was still attached to the skull of a red deer stag, at least five years old, killed in autumn or winter; cut marks on the skull potentially indicating skinning (Ewens 2024a). The inclusion of the antler may suggest ritualised deposition as antler was a valued material in prehistoric Britain and the burial of an unfinished example with no evidence of reworking/recycling was potentially significant (Legge 1981; Worley and Serjeantson 2014). The role of hunting in the earlier Neolithic is reinforced by the lithic assemblage from across the scheme, which included nine leaf-shaped arrowheads all recovered from later features (Devaney 2024i).

The greatest concentration of early-middle Neolithic activity was uncovered at Conington and comprised flint scatters, pits, possible post-holes and utilised tree-throws focused across the gravel ridge at the western end of the site (Fig. 2.5). Three distinct artefact scatters (322320, 322321 and 322322) were identified from which a mixed assemblage of worked flint, including a high proportion of earlier Neolithic blades and middle Neolithic bird-bone impressed Peterborough Ware, was recovered (Devaney 2024g; Percival 2024h; Fig. 2.6). The flint assemblage included blades displaying characteristics associated with Mesolithic or earlier Neolithic soft-hammer blade production (Devaney 2024g). The presence of flint waste, chips and rejuvenation flakes suggests knapping was taking place in the area. The assemblage from the scatters matches that recovered from the surrounding pits where the retouched pieces appear to have been informally worked to create expedient tools. The pits also contained dumps of occupation debris, matching the depositional character of pits found across the country, with pottery sherds, worked and struck flint and broken artefacts recovered from the fills (Garrow 2007, 12; Table 2.4). The ceramic assemblage from the pits included sherds of early Neolithic Plain Bowl and Mildenhall Ware and middle Neolithic Peterborough Ware (Mortlake sub-style; Percival 2024g). Carbonised material indicated the presence of local scrubby taxa including blackthorn and hazel, with rare charred barley and wheat grains (Bailey 2024i; Fosberry 2024); a hazelnut shell from Pit 323667 was dated to 3350-3090 cal BC (SUERC-92413; note unless otherwise stated all radiocarbon dates in this chapter are provided at 95% probability). A saddle quern fragment (F32897), recovered from one of the early Neolithic pits, may imply processing of plant remains. The pits all contained single fills, perhaps representing short-term or rapid events, in some cases linked to in situ burning, with no evidence for the layering of deposits or the accumulation of sterile silting lenses.

| Feature | Diameter (m) | Depth (m) | Fills | Pottery | Sherds | Flint | Finds | Ecofacts | Radiocarbon Date (95.3% probability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pit 320223 | c. 2 | 0.2 | 320224 | - | |||||

| Pit 320299 | 0.3 | 0.09 | 320300 | Plain Bowl | 3 | ||||

| Pit 320301 | 0.4 | 0.18 | 320302 | Plain Bowl | 9 | ||||

| Pit 320305 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 320306-320307 | Several fragments of daub | Three fragments of purging buckthorn charcoal | ||||

| Pit 321703 | 1 | 0.15 | 321704 | Plain Bowl | 3 | 11 | Fragment of saddle quern (F32897 ) | ||

| Post-hole 321724 | 0.3 | 0.24 | 321725 | Plain Bowl | 1 | 1 | |||

| Pit 321868 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 321869 | Plain Bowl | 7 | ||||

| Pit 322816 | 2 | 0.5 | 322813-322815 | Mildenhall Ware | 115 | 38 | |||

| Pit 323677 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 323678 | Peterborough Ware (Mortlake sub-style) | 28 | 1 | Hazel, apple family (pomoideae) and blackthorn charcoal and nutshell fragments (Corylus avellana) | 3350-3090 cal BC (SUERC-92413). | |

| Pit 323786 | 0.5 | c. 0.15 | 323787 | Plain Bowl | 7 | 3 | |||

| Tree-throw 323802 | 1.2 | 0.15 | 323803 | - | Several fragments of animal bone | ||||

| Pit 323804 | c. 1 | 0.15 | 323805 | 2 | |||||

| Pit 323871 | 1.1 | c. 0.3 | 323872 | Mildenhall Ware | 32 | 2 | |||

| Pit 323891 | 1.1 | c. 0.3 | 323892 | Plain Bowl | 1 | ||||

| Pit/Post-hole 323920 | 0.3 | 0.12 | 323921 | ||||||

| Pit 324040 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 324041 | Plain Bowl | 1 | 1 | 1 fragment of a polished Langdale stone axe (F32495 ) | ||

| Pit 324042 | 0.85 | 0.3 | 324043 | 8 |

The extent to which pits represent 'settlement' has been widely debated, with pits often viewed as proxy evidence or repositories for the debris of a variety of activities (Garrow 2007). The pits at Conington do not exhibit a close or clear relationship with surrounding features and so did not form part of a wider landscape complex (Garrow 2006, 34). Rather, these features appear to represent sporadic but persistent activity at the site from the early to middle Neolithic (White et al. 2024). The limited environmental evidence precludes full discussion of the role of agriculture and the development of subsistence strategies, but all represent a level of 'domestic' activity. The positioning of the pits at Conington reflects a broad pattern observed across East Anglia with sites located close to rivers, 98% within 3km, but locally situated at elevated positions (Garrow 2006, 16). The pits at Conington are located on a ridge, c. 12.9m above Ordnance Datum (AOD) at its highest, c. 2.5km to the south of the River Great Ouse, with tributaries bracketing the site in an area of free-draining soils on river terrace deposits. The focus of the activity at Conington may reflect semi-permanent settlement, seasonal occupation, or its role as a key location providing access to surrounding economic resources and culturally significant monumentalised landscapes.

The concentration of features at Conington lies to the south of several sites with evidence for early and middle Neolithic activity. A small assemblage of middle Neolithic Peterborough Ware was recovered from a ditch terminus at Fen Drayton along with residual flint (Slater 2016). Excavations at Barleycroft Paddocks uncovered early Neolithic pottery and flint from tree-throws, and a distinct group of Mildenhall Ware pits (Evans et al. 2016, 15). Further north in Cambridgeshire, little evidence for early Neolithic activity was uncovered at Godwin Ridge and O'Connell Ridge, where extensive excavations in the Over landscape revealed a highly variable pattern of prehistoric activity including early Neolithic flint scatters situated further away from rivers (Evans et al. 2016, 136; 2023). The results of the A14 fieldwalking, discussed previously in a Mesolithic context, also highlight the presence of activity 'inland' with Mesolithic/early Neolithic blade assemblages recovered from non-gravel areas including adjacent to the Bar Hill Landscape Block (FD 72a; Anderson et al. 2009, 39). Regionally, the quantities of earlier Neolithic pottery per hectare from across the A14 were comparable to those at Over but low when compared to sites to the south of Cambridge such as Glebe Farm, Trumpington Park and Ride (Knight 2018) and North Fen, Sutton Gault (Knight 2016). Over 50% of the earlier Neolithic ceramic assemblage from the A14 excavations was recovered from later features, potentially indicating a more variable and widespread pattern of activity concentrated at key locations (Percival 2024h). The distinctly limited early Neolithic evidence, relying principally on scatters and residual evidence, raises questions surrounding the potential nature of this activity and its implications in understanding population densities and occupation patterns.

Later Neolithic settlement activity along the A14 is equally varied and transient, comprising pit groups and activity in the vicinity of palaeochannels (Table 2.3). The former riverbank of the River Great Ouse lay at the western extent of the River Great Ouse Landscape Block, with a sequence of peats and alluvial deposits identified during the evaluation works (Area C2 and N1; Patten et al. 2010, 92-3). The basal peat deposits, first appearing at a depth of -3m around 20-25m east of the present riverbank, likely formed during the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age. The lower peat deposits contained a small lithic assemblage along with a considerable quantity of burnt and fire-cracked stones and a wooden post, dated to 2190-1940 cal BC (Beta-270667), indicating activity at the river edge (Patten et al. 2010, 92). An area of buried soil (190196) extending over 60m ² was identified c. 150m to the east of the former riverbank (Atkins and Douthwaite 2024), and an assemblage of Neolithic flint, including flakes, bladelets, two end-scrapers and a burin, was recovered from a pit associated with this soil (Devaney 2024e). Elsewhere across the River Great Ouse Landscape Block, the lithics retrieved included Neolithic forms such as a flaked axe (F70571), scrapers and later Neolithic chiselled arrowheads. Although largely recovered from later features, these worked flints highlight the presence of a range of activities undertaken in this landscape, including knapping. In sum, the evidence recovered at River Great Ouse points to continuity in prehistoric activity along the riverbanks, the surrounding channels and on the gravel terraces.

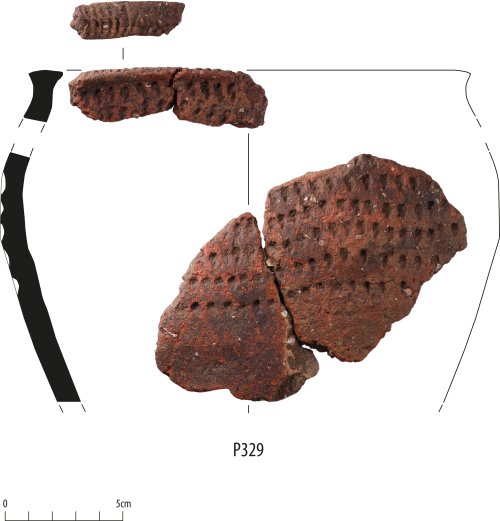

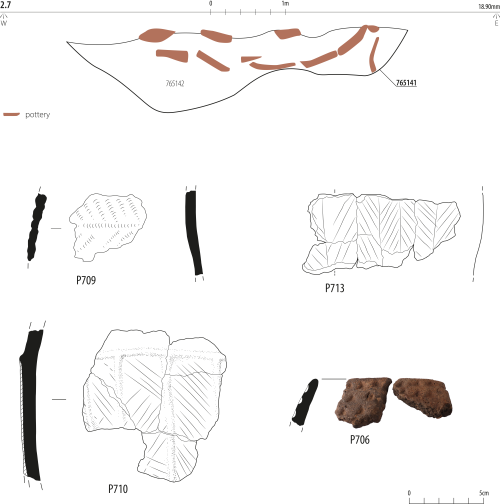

At Brampton West, activity was also concentrated around a palaeochannel and a possible occupation deposit of burnt clay, charcoal and burnt stones. A small assemblage of worked flint, a single sherd of Grooved Ware, 25 sherds of undiagnostic prehistoric pottery and faunal remains were recovered from this deposit (Percival 2024c). The faunal remains comprised solely butchered cattle and ovicaprid long bone and rib fragments (Faine 2024b). The assemblage was comparable to that of Pit Group 7BC.274, located c. 230m to the south-west, which contained several burnt ovicaprid long bone fragments, 205 sherds of late Neolithic Grooved Ware from 24 vessels, and 25 pieces of worked flint (Devaney 2024c; Percival 2024c). The worked flint assemblage contained cores and tools including three scrapers, a backed knife and a retouched flake (Devaney 2024c). The pit fills may represent curated and deliberately deposited material potentially resulting from feasting activity, with tentative evidence for the deliberate placement of the Grooved Ware sherds within one of the pits (Pit 765141). This pit contained sherds from 15 vessels including large sherds from seven Durrington Walls tub-shaped vessels with vertical pinched cordons defining panels in-filled with incised decoration (Percival 2024c; Fig. 2.7). The sherds were arranged in layers around the sides of the pit and placed carefully within the single fill, as opposed to forming part of an incidental dump of material within a soil matrix. This conforms to a more widely recognised pattern at sites such as Over, Cambridgeshire, indicative of the increased structured 'formality' of Grooved Ware pit deposits (Thomas 1999; Pollard 2001; Garrow 2006, 89; Noble et al. 2016).

A total of c. 24 Grooved Ware vessels were recovered from three landscape blocks: Brampton West, West of Ouse and River Great Ouse, with that from a pit at Brampton West forming the largest assemblage (Percival 2024h). The Grooved Ware is predominantly grog-tempered with forms and decorations characteristic of the Durrington Walls substyle. A comparable pit at Longstanton contained a large assemblage of 165 sherds of Grooved Ware, also of Durrington Walls substyle, from two charcoal-rich fills (Paul and Cuttler 2008, 4). This feature was associated with further pits, post-holes, ditches and gullies suggesting wider activity but with limited clustering of features (Paul and Cuttler 2008, 5-7). The pattern of Grooved Ware distribution across the region typically indicates a preference for riverside locations with the A14 largely conforming to this (Cleal 1999; Knight 2016, 161; Chris Evans pers. comm.). Contrasting with these specific concentrations of activity, recent comparative studies have also highlighted the absence of Grooved Ware from many extensively excavated riverine locations, potentially indicating areas that were uninhabited or rarely utilised (Evans et al. 2023). The complexities of Grooved Ware distributions have been highlighted with the suggestion at Over, Cambridgeshire, that the Durrington Walls substyle was focused around the palaeochannel at Godwin Ridge. Grooved Ware was recovered from a limited number of dispersed pits and tree-throws at Godwin Ridge with a higher density of later Neolithic pits uncovered at O'Connell Ridge adjacent to a palaeochannel (Evans et al. 2016, 237). It has been suggested that Grooved Ware of the Durrington Walls substyle is more typically associated with dispersed pits and pit groups; a pattern also seen at sites such as Linton Village College, Margetts Farm, and now across the A14 (Pollard 1998; Percival 2012; 2024h; Knight 2016, 220; Ingham and Oetgen 2016). Ongoing excavations at Needingworth Quarry (Over) in the lower reaches of the Great Ouse, where the river entered the low-lying land of what became the fen basin, are revealing an extensive Neolithic landscape. This includes pits with Mildenhall and Grooved Ware associations, structural remains, oval barrows and a linear series of long rectangular monuments (Tabor and Barker 2022; Brudenell et al. 2023). These were located south of the causewayed enclosure in Haddenham's Upper Delphs (MCB7035) and the Foulmire Fen long barrow (MCB9398; Evans and Hodder 2006). The distribution of activities reveals a focus on the tributaries and main channels of the Great Ouse river system, where later prehistoric communities also settled and farmed prior to the submergence of the basin by Fen deposits in the late Bronze Age.

Evidence for Neolithic subsistence strategies across the A14, indicated by the cultivation of cereals and animal husbandry, was limited. The remains from the A14 offer few insights into this debate with poorly preserved grains only indicating the presence of glume wheats and barley (see Environmental Overview in Wallace and Ewens 2024). The presence of a single fragment of a saddle quern from an early Neolithic pit at Conington provides tentative evidence for cereal processing. The continued use of wild resources is reflected in the archaeobotanical samples, with hazelnut shells and shrubby fruit-producing taxa represented. The archaeozoological assemblage from Neolithic features across the A14 also comprised both wild and domesticated species including red deer from the pit at West of Ouse, predominantly antler likely used for tool production, and domesticated sheep (adult and infant) from the early-middle Neolithic pits at Conington. The A14 Neolithic flint assemblage contained a variety of tools including those potentially associated with hunting, animal butchery and hide-processing. Diagnostically later Neolithic lithics included chisel and oblique arrowheads, often associated with Grooved Ware, with the most complete examples recovered from Fenstanton Gravels (Devaney 2024i).

The impact of Neolithic inhabitation on the environment has often been explored through woodland clearance, with many of the 46 samples analysed from the A14 indicating the presence of scrubby woodland with wood charcoal (Wallace and Ewens 2024). The clearance of woodland was identified by tree-throws associated with Neolithic artefacts or activity at West of Ouse and Conington. This mirrors the evidence from neighbouring sites with over 300 tree-throws dating to the Neolithic uncovered during excavations at Huntingdon Racecourse (Macaulay 1993). The pollen records indicate that woodland clearance was variable across the region, ranging from minimal to intensive deforestation at different locations during prehistory (Smith et al. 1989; Scaife 2000). Extensive palaeoenvironmental and drainage studies at Over, Cambridgeshire, identified mixed-oak woodland until the late Neolithic (Evans et al. 2016, 80). This pattern was also seen in the palynological record from the palaeochannels at River Great Ouse (Grant 2024e). The occurrence of localised management of woodland, while more difficult to recognise, was likely and may have opened up landscapes to provide space for growing crops, grazing, hunting and the construction of monuments (Evans and Hodder 2006; Lyons 2019). Neolithic populations along the A14 appear to have been moving within a diverse environment, potentially exploiting both wild and domestic resources and leaving only sllight traces of settlement evidence and subsistence activities.

The paucity of later Neolithic settlement evidence on the A14 is juxtaposed against the proliferation of monuments along the River Great Ouse during the Neolithic-Bronze Age. Several monumental complexes with their origins in the Neolithic have been identified along the River Great Ouse including at Buckden-Diddington (Malim 2000), Eynesbury, St Neots (Malim 2000; Ellis 2004), Margetts Farm, Buckden (Ingham and Oetgen 2016) and Rectory Farm, Godmanchester (Lyons 2019). Recent excavations have revealed extensive Neolithic activity across the river's eastern terrace within the Over landscape including four Neolithic barrows, enclosures and henges (Evans et al. 2023). This is in addition to the cremation burials at O'Connell Ridge (Evans et al. 2016) and the Haddenham causewayed enclosure (Evans and Hodder 2006). The broad distribution of monuments appears to focus on the river, with the Over landscape extending into this to accentuate the meeting point of river and Fenland (Evans et al. 2023). The Neolithic monuments of the A14 may also reflect an emphasis on riverside settings, with Neolithic activity concentrated within the western portion of the scheme at Alconbury and West of Ouse.

The Neolithic enclosure (Monument 1) uncovered under the Bronze Age barrow at West of Ouse was constructed following a phase of clearance indicated by a series of pits and tree-throws across the interior of the enclosure. The clearance of trees prior to the creation of monuments has been identified at sites across the Ouse Valley, with the act of construction serving both a practical and symbolic function in modifying the landscape (Evans and Hodder 2006; Lyons 2019, 399). West of Ouse Monument 1 was aligned north-east to south-west and was defined by an elongated C-shaped ditch enclosing an area of c. 31.5m by 14.5m with an entrance to the north-west. There was no evidence to indicate that the enclosure continued to the north, with the later barrow likely matching its extent. The monument was distinctly elongated in shape, contrasting with the circular form of many of the ring-ditches and henge-type monuments, and is in some respects reminiscent of an early Neolithic oval barrow such as that defined by a U-shaped ditch at Horton in the Middle Thames Valley, Berkshire (Ford and Pine 2003). The lack of evidence for funerary activities, coupled with the presence of an entranceway, however, invites closer parallels with Neolithic enclosures that may have fulfilled a range of ceremonial functions (Bradley 1998; 2003; Gibson 2012a). The enclosure is similar to the 'paper-clip' shaped enclosure identified, but unfortunately not investigated further, at Buckden-Diddington and the enclosure that forms part of the ceremonial complex at Octagon Farm, Cardington-Cople, Bedfordshire (Malim 2000, 72; Fig. 2.8). At Needingworth Quarry, Over, a narrow ditch, devoid of artefacts, defined an elongated enclosure c. 30m in length (Tabor and Barker 2022, 31). Three oval enclosures were identified at Biddenham Loop, Bedfordshire, of comparable dimensions to that at West of Ouse, measuring 25-40m in length and 14-16m in width (Luke 2008, 81). The limited material culture, including a small lithic assemblage and no pottery, recovered from West of Ouse Monument 1 provides few insights into the activities that may have taken place there and whether they were of a quotidian, ceremonial or mortuary nature. While different in form, the unusual trapezoidal enclosure excavated at Rectory Farm, Godmanchester, to the north of the West of Ouse Landscape Block, provides a framework in which to consider the role of enclosure (Lyons 2019). As at Rectory Farm, the monument may best be understood as a demarcation of an important space, invested in by a community and potentially representing a fixed point and transformed 'space' within the landscape (Bradley 1998; Brück 2000; Lyons 2019). Perhaps the most revealing insight into the significance of the enclosure is the development of the Bronze Age barrow directly on top.

The challenges in interpreting circular or oval enclosures and henge monuments pervade our understanding of the ditched monument at Alconbury (Fig. 2.9). This monument comprised two opposing ditch arcs encircling an area 20m in diameter with entrances to the east and west. The ditches measured 2.2-2.4m in width and 0.55-0.56m in depth with fills accumulated through natural silting. The presence of slumped gravel and stone fills may have accumulated from the erosion of an outer bank. The monument at Alconbury displays characteristics central to the early classification of henges, namely an external bank, wide ditch and two entrances (Atkinson 1951, 85; Wainwright 1969; Gibson 2012b; Cummings 2019). The term 'henge' encompasses a broad range of monumental forms with debates often focusing on the diversity of forms as opposed to explaining function (Younger 2016, 119). Henge monuments have been interpreted as potentially commemorative, constructed as ceremonial spaces placed at key points in the landscape perhaps associated with rivers and routeways (Bradley 1998; Younger 2016). The henge at Alconbury is located at the edge of a river terrace at the confluence of two tributaries of the River Great Ouse surrounded by what was likely a seasonally flooded landscape.

The dating of henges can be problematic with the monument at Alconbury presenting a familiar set of challenges with mixed material recovered, potentially resulting from later surrounding activity rather than relating to the construction of the monument. Moreover, the ditch may have been open and kept clean for a considerable period before the initial fill accumulated (Gibson 2012b, 13). Charcoal from the basal fill was radiocarbon dated to 1880-1620 cal BC (SUERC-85531) providing a broad date for ditch silting. A comparative radiocarbon date of 1900-1690 cal BC (SUERC-75283) was obtained from charcoal within a pit truncating the northern terminus. Additionally, a mixed ceramic assemblage was recovered from the ditches including sherds of early Neolithic wares and a larger assemblage of early Bronze Age Collared Urn fragments, highlighting the potential longevity of this monument. A cremation burial located 4m south-east of the monument was also dated 2030-1880 cal BC (SUERC-91510) hinting at the range of activities potentially taking place around the henge during this period. On balance, the henge appears to have been constructed prior to the early Bronze Age with the dearth of cultural material and interior features matching the depositional patterns observed at other sites. The henge ditch began silting in the early Bronze Age, possibly coinciding with the 'reactivation' of the monument as a funerary site. This trend is observed at other locations along the A14, principally at Brampton West, and regionally, such as at Needingworth Quarry (Evans and Vander Linden 2008; Cooper et al. 2022).

The Bronze Age evidence is a tale of two scales, with the scattered evidence of settlement contrasting with the proliferation of monuments (Table 2.5). The pattern of early Bronze Age (2300-1500 BC) activity is characterised by dispersed occupation evidence, in contrast to the proliferation of monuments and burial activity. Early Bronze Age settlement can be compared to sites across the region, with pits continuing to provide a key resource for exploring occupation patterns. Regionally, the scale and intensity of activity in the middle Bronze Age (1500-1150 BC) actively transforms the landscape by extensive boundary construction through the development of enclosures and field systems. Despite the scale of the A14 excavations, the construction of enclosures and field systems was only evident at a single location - Conington. The creation of boundaries at Conington is comparable to sites to the north of the A14, such as Fenstanton, Northstowe and Over, extending activity from the Fen to the river's edge. The elusive evidence of later Bronze Age (1150-800 BC) activity on the A14 paints an increasingly complex regional picture of settlement extent, distribution and intensity that extends into the early Iron Age.

| Landscape Block | Period | Character | Features | Monuments | Burials | Pottery Summary | Finds of Note | Animal Bone Summary | Palaeobotanical Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alconbury | Late Bronze Age-early Iron Age | Funerary | Inhumation Burial 5.276 | Undiagnostic | Fired clay cylindrical weight (F02018); A bronze awl (F55952 ) | ||||

| Brampton West | Early Bronze Age | Occupation; Funerary | Pits; Structure | Ring-ditch 10.433 | Cemetery 103 Cemetery 200 | Collared Urns | Amber beads and pendants (F12713

F12714

F12715

F12716

F12717

F12718

F12719

F12720

F12721

F12722 ); A bronze double-edged knife with a rivetted tang (F12112);

A jet stud (F12130 ); a bronze side-looped socketed spearhead (F12051 ) | Cattle; sheep/goat; pig; horse; dog; wild game; wild fowl. | Dominated by hazelnut shell fragments with occasional remains of charred cereals. |

| Early-middle Bronze Age | Monumental; Funerary | Monument 200 | Inhumation Burial 12.7 Inhumation Burial 12.9 Cremation Burial 12.233 | Collared Urn; Beaker | |||||

| Middle Bronze Age | Occupation; Funerary | Pits; Ditches | Cemetery 202 Cremation Burial 12.234 | Deverel-Rimbury | |||||

| Middle-late Bronze Age | Funerary | Cremation Burial 7BC.99 Cremation Burial 7BC.73 Cremation Burial 7BC.127 | |||||||

| Late Bronze Age-early Iron Age | Occupation | Pits | |||||||

| Brampton South | Late Bronze Age early Iron Age | Pit Alignment | |||||||

| West of Ouse | Early Bronze Age | Monumental; Funerary | Monument 2 | Cemetery 1 | Grog-tempered | Cattle; pig | Cereal grain; spelt; grass seeds; emmer; ribwort plantain. | ||

| Middle Bronze Age | Funerary | Cemetery 2 | Cremation Urns | Bronze fragments (F16337 and F16336 ) | |||||

| Late Bronze Age-early Iron Age | Pit Alignment | ||||||||

| River Great Ouse | Early Bronze Age | Monumental | Monument 1 | ||||||

| Fenstanton Gravels | Bronze Age | Occupation | Pits | Inhumation Burial 27.9 | A copper-alloy awl (F27195 ) | Catttle; sheep; pig; deer | Charred cereal; barley. | ||

| Early Bronze Age | Occupation; Funerary | Tree throws; Pit | Inhumation Burial 28.505 | Grog-tempered | 3 copper-alloy finger rings (F28013 , F79175 , F79176 ) | ||||

| Middle Bronze Age | Occupation; Funerary | Pits; wells; waterhole | Cemetery 1 Cemetery 3 Cremation Burial 29.13 Cremation Burial 29.14 | Deverel-Rimbury | Amber bead (F28019 ); Copper-alloy blade fragment (F28016 ) | ||||

| Conington | Bronze Age | Monumental | Monuments 1-3 | Cattle; sheep/goat; horse; dog; pig | Charred cereal grains; grassland and scrub taxa; sloe; hawthorn. | ||||

| Early Bronze Age | Occupation | Enclosures; pits | Grog-tempered | ||||||

| Middle Bronze Age | Occupation | Enclosures; wells; pits | various shell-tempered | ||||||

| Middle-late Bronze Age | Occupation | Field system; cattle burials | shell-tempered |

In contrast, extensive evidence of Bronze Age monumental and burial activity was identified including ring-ditch monuments and barrows, often associated with later large cremation cemeteries and inhumation burials spatially referencing them. The monuments of the A14 developed in the late Neolithic-early Bronze Age, with extensive evidence of middle Bronze Age modification and reuse. Late Neolithic-early Bronze Age monuments include ceremonial spaces, timber circles, henges, and barrows, the latter generally associated with funerary concerns. Bronze Age monuments were principally focused within the western portion of the scheme at Brampton West, West of Ouse and River Great Ouse. Several of the monuments were linked to burial activity, such as the barrow at West of Ouse, with a range of mortuary rites and funerary practices including inhumation burials, smaller groups of cremations, and large cremation cemeteries uncovered across the scheme. The cemeteries and individual burials uncovered at Brampton West, West of Ouse and Fenstanton Gravels provide a focus for discussion and offer valuable insights into Bronze Age funerary practices.

The Bronze Age witnessed significant environmental change, with the drainage studies conducted at Over, Cambridgeshire, highlighting its impact on the actual river itself; the once well-defined braided plains transformed into silt-choked channels in the Bronze Age (Evans et al. 2016, 61). The impact of marine transgression was also evident during this period, with intertidal mudflats developing followed by freshwater conditions allowing for the development of peats, wet woodland and the deposition of clay silts in the late Bronze Age (French and Heathcote 2003; Evans et al. 2016, 62; Evans 2022, 132). Palaeoenvironmental investigations at Over also revealed a complex pattern of woodland decline in the early Bronze Age potentially reflecting the impact of marine transgression, increasingly high groundwater conditions and human action (Evans et al. 2016, 80). As mentioned earlier, the pollen records from across the region indicate that woodland clearance shows much variation in intensity across different landscape locales throughout prehistory (Smith et al. 1989; Scaife 2000; Scaife and French 2020, 33-36). At River Great Ouse, pollen preserved in the palaeochannels indicated the presence of woodland and scrub (comprising oak, alder, and ash) during the early Bronze Age (Grant 2024e). Evidence of disturbance from pastoral activities and clearance is not evident until later in the Bronze Age, with widespread deforestation and the transition to open grassland only occurring well into the Iron Age.

As more nuanced understandings of Neolithic agricultural adoption have come to the fore, highlighting themes of regionality, variability and mobility, the development of agricultural practices in the Bronze Age has also been subject to discussion (see Stevens and Fuller 2012; 2015; Bishop 2015; Rowley-Conwy et al. 2020). The evidence from Bronze Age features across the A14 indicates a greater presence of domesticated species, alongside the continued use of wild resources, with the extent of cereal cultivation highly debatable. The relatively small animal bone assemblage, 2670 fragments, primarily comprised cattle and sheep with limited evidence for other domesticated animals including horse and dog (Wallace and Ewens 2024; Table 2.6). In some instances the largest assemblages were recovered from monuments such as the ring-ditch (Monument 200) at Brampton West from which 95% of the assemblage from Brampton West derived. The animal bone assemblages from the monuments are potentially from feasting rather than reflecting everyday domestic life, but when viewed collectively contribute to a clear picture of Bronze Age husbandry, with a focus on maintaining herds of cattle and flocks of sheep/goat (Table 2.6). Metrical analysis indicated that late Bronze Age cattle had a stature of 108-110cm, falling within the range expected for domesticated animals. The importance of cattle in the Bronze Age is noted at sites across the region including Godwin Ridge and O'Connell Ridge, Over (Evans et al. 2016, 184). The potential exploitation of wild resources was also evident in the assemblages from the A14 with deer, bird and fish identified, including a single vertebra from a marine fish of the cod family (Gadidae) at Alconbury (Cussans 2024).

| Species | Brampton West | Brampton South | Conington | Fenstanton Gravels | West of Ouse | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domesticates | ||||||

| Cattle | 198 | 15 | 290 | 48 | 26 | 577 |

| Sheep/goat | 41 | 5 | 14 | 18 | 78 | |

| Goat | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Pig | 15 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 27 | |

| Horse | 9 | 14 | 23 | |||

| Dog | 8 | 12 | 20 | |||

| Large-sized mammal | 132 | 16 | 336 | 142 | 5 | 631 |

| Medium-sized mammal | 43 | 20 | 15 | 57 | 3 | 138 |

| Small mammal | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Deer | ||||||

| Deer, red | 3 | 4* | 1 | 9 | ||

| Deer, roe | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Deer, unidentified | 1 | |||||

| Hare, brown | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Rabbit | 4◊ | 4 | ||||

| Fish | ||||||

| Carp (family) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Gadid sp. | 1 | |||||

| Bird | ||||||

| Bird, unidentified | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Chicken/duck size | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Goose size | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Wader/plover | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Passerine, large | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Passerine, small | 1 | 1 | ||||

The palaeobotanical evidence for arable agriculture is far more uncertain, with the assessment of 245 samples from Bronze Age contexts, associated with both settlement and monuments, revealing limited plant remains. It is striking that across the A14 fewer than 100 cereal grains were recovered from features of this date, with the species represented including emmer and spelt wheat and barley (Wallace and Ewens 2024). The charred plant remains from Godwin Ridge, Over, provide a similar picture with cereals, including wheat, barley and flax, present along with charred wild seeds (Evans et al. 2016, 185). While the importance of cereal cultivation in the Bronze Age is debated it is worth noting that over half the Bronze Age cereals from the scheme were recovered from the urned cremations at West of Ouse. The inclusion of potentially economically significant cereals as grave goods (explored in the proceeding sections) may foreshadow the investment in and impact of landscape division later in the Bronze Age.

The evidence for early Bronze Age settlement and subsistence is limited to dispersed pits found across the A14, with examples at Brampton West and Fenstanton. The earliest Bronze Age evidence at Brampton West was limited to a single ditch and a post-hole containing Beaker pottery. The pottery from the ditch was recovered from a burnt deposit and was decorated in a style typical of domestic Beaker, with rusticated fingertip impressions (Percival 2024c). Further early Bronze Age evidence comprised a possible structure and small pits located within the north-eastern area of the landscape block, with middle Bronze Age pottery recovered from pits to the west. A similar picture is presented at Fenstanton Gravels, where dispersed pits contained flints and pottery of early Bronze Age date. A small range of tools from across the A14 could also be attributed to the early Bronze Age including barbed and tanged arrowheads and plano-convex knives (Devaney 2024i). The pattern of early Bronze Age activity identified through scattered pits is mirrored regionally at sites such as Church Farm, Fenstanton, located c. 2km NNW of Conington (Chapman et al. 2005). Here, Beaker pottery was recovered from a group of seven intercutting pits representing five sequential episodes of deposition. The pits were charcoal-rich containing hearth debris, flint waste, cattle bone, and carbonised seeds of cereals including spelt, bread wheat and barley (Chapman et al. 2005, 18).

The evidence from Brampton West and Fenstanton Gravels contrasts with that from Conington where evidence for an early Bronze Age enclosure was uncovered (Fig. 2.10). The rectangular enclosure (Enclosure 1), measuring c. 66m long by 64m wide and orientated NNW-SSE, was uncovered on the southern edge of the gravel ridge and continued beyond the excavated area. Two possible post-holes and four clay-lined pits lay within the enclosure, the latter containing Collared Urn pottery. The enclosure was reactivated in the middle Bronze Age through the recutting of its ditches, and together the features appear to represent small-scale settlement activity focused on pastoralism. The early Bronze Age features at Conington are significant in marking the commencement of more intensive agriculture at the site, which would develop further in the middle Bronze Age. Beaker pits potentially associated with a three-sided enclosure, surrounding an area c. 40m in width, were also uncovered at Margetts Farm, Buckden, located to the south of the A14. A pit situated to the east of the enclosure contained an assemblage of seven fine ware and two domestic-style Beakers with burnt residues (Ingham and Oetgen 2016, 15). Studies of the distribution of Beaker sites across East Anglia have highlighted their close spatial connections with rivers and their heterogeneous characters in terms of features and finds present (Bamford 1982; Garrow 2006). Beaker settlements of varying size and complexity have been excavated across the region, with many indicative of relatively low levels of activity (Evans et al. 2016, 203). Significant late Neolithic-early Bronze Age activity comprising three dwellings, multiple monuments and four burnt mounds was uncovered at Kings Dyke/Bradley Fen, but even here the impression is one of episodic or short-term occupation (Knight and Brudenell 2020, 140). The evidence from the A14 contributes to this interpretation, with the scattered evidence potentially resulting from intermittent or peripheral activity.

The increased archaeological visibility of features from the middle Bronze Age onwards on the A14, comprising pits, wells, enclosures and animal burials, contrasts with the more limited distribution of evidence. Middle Bronze Age activity on the A14 was again confined to two landscape blocks: Fenstanton Gravels and Conington. The middle Bronze Age (1500-1150 BC) activity at Fenstanton Gravels comprised cremation cemeteries and settlement evidence concentrated at a significance distance (c. 0.7km) away from the largest cemetery (cemetery 3) and dispersed throughout the landscape block (Fig. 2.11). Settlement evidence comprised scattered pits, with the animal bone assemblage indicating evidence of cattle, sheep/goat and pig husbandry and butchery; bone and horn working was also noted (Ewens and Cussans 2024). Significant 'domestic' activity was potentially denoted by the presence of two middle Bronze Age pits or wells located towards the centre/northern edge of the main TEA 28 excavated area. A total of 835g of pottery from three Deverel Rimbury vessels and a Bucket Urn was recovered from the largest pit (Pit 280917) along with a worked sheep metapodial (F78670), possibly a pin (Fig. 2.11a). The large animal bone assemblage from the pits included cattle, mainly mandibles and teeth, but also fore- and hind-leg bones. Marks on these bones were indicative of all stages of processing from primary butchery to dismemberment into joints, representing the consumption of prime and moderate quality beef.

Middle Bronze Age activity at Conington included the recutting of the earlier Bronze Age enclosure, the establishment of a large enclosure, co-axial field systems (Field Systems 3 and 5), several waterholes/wells and three small ring-ditched monuments (Fig. 2.12). The expansion of rectilinear field systems and enclosures in southern England in the second and early first millennium BC, potentially linked to social, cultural and economic changes, is widely recognised (Brück 2000; Yates 2007). The enclosures and field systems at Conington represent the sole example of the creation of Bronze Age bounded landscape blocks across the entirety of the A14. The earlier Bronze Age ditches of Enclosure 1 were recut in the middle Bronze Age with an assemblage of shell-tempered pottery from an undecorated straight-sided urn recovered from the ditch defining the northern edge of the enclosure (Percival 2024g). Contemporary Field System 1 was located c. 45m to the north of Enclosure 1 and comprised two ditches aligned north to south and east to west, with other sides of the field block probably truncated. A small animal bone assemblage was recovered from the ditches, comprising cattle, sheep/goat, horse and fragments of large and medium-sized mammals (Ewens 2024c). A more extensive field system, Field System 3, was located to the east enclosing an area of at least 330m by 120m divided into four or more field blocks (Fig. 2.12). This comprised 12 ditches, principally aligned NNW-SSE, with its role in cattle husbandry highlighted by the presence of a cattle burial adjacent to the northern ditch terminus. A second cattle burial was uncovered within a large sub-circular pit at the north-western edge of Field System 5, c. 100m to the east of Field System 3. This articulated cattle skeleton exhibited evidence of butchery around its neck and rump.

The alignment of the field systems and particularly the connection between Enclosure 9 and Field System 5 immediately to its east suggests the enclosure may have formed the primary focus or 'spine', with the field systems developing on the same alignment and building out from these. Enclosure 9 measured c. 100m in length and c. 95m in width on an NNW-SSE alignment (Fig. 2.13). The earliest phase comprised three ditches from which a hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) seed provided a radiocarbon date of 1220-1010 cal BC (SUERC-92420). An adjoining enclosure may have extended south beyond the limit of excavation and was cut by the later remodelling. The enclosure was augmented and enlarged through the additions of Ditch 33.102 along the northern and western edge and Ditch 33.103 to the south. The southern entrance was maintained, suggesting the earlier adjoining enclosure may still have been in use. Four wells surrounded the north-western portion of Enclosure 9, in some cases cutting the earlier enclosure ditch, from which a limited environmental and artefactual assemblage was recovered. Well 33.114 cut the earlier enclosure ditch and a fragment of blackthorn charcoal (Prunus spinosa) from its primary fill was radiocarbon dated to 1520-1420 cal BC (SUERC-92416). Based upon the stratigraphic relationships this charcoal appears to represent residual Bronze Age activity rather than providing a date for the construction of the well. The wells contained waterlogged deposits from which an abundance of hedgerow taxa was identified, suggesting that several of the boundaries may have been delineated by hedgerows (Fosberry 2024). The placement of the wells indicates they formed important components of a wider enclosure system that developed during the middle-late Bronze Age (1500-800 BC) and may have included Field System 5. This field system extended to the north-east on the same alignment as Enclosure 9, with the narrow ditches dividing four field blocks associated with a possible trackway.

The development of enclosures is often linked to an emphasis on pastoralism and the increased importance of livestock, with cattle dominating assemblages from the Fen region including from Conington (Evans et al. 2011, 35; Ewens 2024c). The placement of the boundaries at Conington, primarily across low-lying areas associated with palaeochannels, likely provided access to damp grassland pasture as reflected in the palaeobotanical assemblages from the wells (White et al. 2024; Fosberry 2024). The boundaries uncovered at Conington, potentially extending for considerable distances beyond the excavated areas, present an incomplete picture, with several key features missing usually ascribed to 'typical' middle Bronze Age settlement, namely post-built roundhouses and storage pits (Brück 1999; 2000). The complexities of settlement, population and seasonality is exemplified by the analysis of the later Bronze Age evidence at Godwin Ridge, Over, where evidence for between only three and five roundhouses contrasts markedly with the 85,000 pottery sherds recovered from surface spreads (Evans et al. 2016, 202). It has been proposed that this settlement may have included a small resident population with additional seasonal activity including trade, fishing, and gatherings, developing a well-connected enhanced community occupying a key ridge top location (Evans et al. 2016, 203). This is not to suggest the same model for Conington but the features at this site potentially represent a peripheral or transitional landscape with the role of movement and seasonal activities often overshadowed by the seeming permanence of settlement when compared to earlier periods (Brück 2000; 2007). The importance of settlement and field boundaries in the Bronze Age has been explored not only in terms of transformations in agriculture but also in changing expressions of tenure, connectivity and separation, and the functional and symbolic significance of divided and bounded landscapes (Brück 2000; 2007; 2019; Johnston 2001). At Conington, three ring-ditches (Monuments 1-3) of comparable size, measuring 8-10.5m in diameter, were located within the field systems (Figs 2.13, 2.16). Their forms were suggestive of small early Bronze Age barrows and the placement of Monuments 2 and 3 in relation to Enclosure 9 is striking and reminiscent of the relationship identified at Barleycroft, Over (Evans and Knight 2000). Although these 'barrows' were undated, the field systems appear to reference/respect the earlier monuments, harnessing them within their boundaries, perhaps linked to the marking of place.

The duration of activity at Conington is uncertain as the field systems and enclosures produced few finds. The small ceramic assemblage contained no distinctly late Bronze Age wares, suggesting that the site may have largely gone out of use by the end of the second millennium BC. This raises questions surrounding developments in the late Bronze Age-early Iron Age where evidence is distinctly limited from the A14 (Table 2.5). The key features that have been assigned to this period, admittedly based on comparative analysis as opposed to the recovery of chronologically diagnostic material, comprise three pit alignments (Fig. 2.14). At West of Ouse, two pit alignments (Linear Boundary 1 and 2) appear to respect the position of the Bronze Age barrow (Monument 2). The extensive pit alignment (Linear Boundary 1) comprised 103 closely spaced pits extending for c. 270m. The pits were circular (c. 1m in diameter) to oval (c. 2-2.5m × 0.5m) in shape and contained single fills. Pits of comparative form defined a further pit alignment to the south of the barrow (Linear Boundary 2). The alignment comprised 14 ovoid pits from one of which worked flint and seven sherds from the base of an early to middle Bronze Age urn were recovered (Pit 161596). The pit alignment at Brampton South comprised 60 circular and sub-circular pits, of which 54 were hand excavated, with the geophysical survey indicating the alignment continued for c. 400m. The eastern end of the alignment was formed by a double row of pits spaced c. 4.5m apart with the northern row visible for c. 20m. The pit alignment at Brampton South seemingly continued to exert an influence over the orientation of the Iron Age settlement boundaries (see Chapter 3), indicating that its significance endured over a lengthy time-frame. A similar suggestion has been made for the influence of a c. 116m long pit alignment, comprising 35 pits, on the development of Iron Age boundaries at Bearscroft Farm, Godmanchester (Patten 2016, 22). Pit alignments within the Great Ouse Valley generally date to the late Bronze Age-early Iron Age (Pryor 1993; Pollard 1996, 110; Walker 2011, 5). In several cases, as at West of Ouse, they appear to reference earlier monuments or natural features potentially accentuating and linking significant areas. At Haddenham, Bedfordshire, a large pit alignment connected the two sides of a bank along a river bend (Dawson 2000) and at St Ives, Cambridgeshire, two pit alignments ran parallel to a former course of the Ouse (Pollard 1996, 99). At West of Ouse there is a clearer association between the pit alignments and the barrow. At Brampton a 'ceremonial complex' lies c. 2.5km north of the site, with the pit alignment potentially designating a key routeway between areas.

The limited evidence of late Bronze Age activity along the A14 raises several questions surrounding settlement distribution and identification. To the north of the A14, late Bronze Age-early Iron Age activity was identified during the peripheral works at Northstowe including pits, ditches and pit clusters; many of these contained rich artefactual and environmental assemblages (Collins 2016, 20). At Cambridge Road, Fenstanton, evidence of late Bronze Age-early Iron Age activity was uncovered comprising two large intercutting pits, a trackway, a possible four-post-structure and cremation burials (Ingham 2022, 16). While more limited in area, this concentration of features is greater than that uncovered from other sites along the A14. The lack of evidence may be partially explained by a shift in activity as witnessed at Godwin Ridge, Over, where the development of enclosures during the middle Bronze Age was superseded by large late Bronze Age surface middens (Evans et al. 2016, 144). This may simply be disguised by the significant later settlement from the middle Iron Age onwards perhaps truncating or recutting late Bronze Age-early Iron Age features, but across the A14 there does appear to be a demonstrable lack of later Bronze Age activity.

The paucity of Bronze Age settlement evidence contrasts with the extensive evidence of monumental and burial activity (Fig. 2.15). Circular and sub-circular ditched monuments form an integral part of a monumental tradition that spans the Neolithic and Bronze Age transcending other social, cultural and economic developments and divisions (Bradley 1998; Fig. 2.16). The classification of such sites is more than a semantic issue as at its core lies a distinction between a monument for the living or a monument for the dead. The debate provides a focus on the primary purpose of monuments, yet few remain static with many displaying evidence for the changing nature of activity over extensive time-frames, through remodelling and reuse. The monuments of the A14 arguably formed part of a busy monumental landscape marked throughout prehistory by sites often with long histories of significance.

The longevity of activity at particular locations in the landscape is demonstrated by the development of the Bronze Age barrow at West of Ouse (Figs 2.17 and 2.18). The Neolithic enclosure previously described (Monument 1) was overlain by a large early Bronze Age barrow (Monument 2). The circular barrow had an internal diameter of c. 38m and comprised a central mound with surviving deposits up to 0.8m high, resulting in a slight rise visible prior to excavation, surrounded by a deep ditch. The barrow mound capped the Neolithic enclosure ditch and its internal features, and a buried soil horizon with evidence of human activity and trampling (MacPhail and Carey 2024a). The base of the mound was constructed from layers of dumped soil with silt loams, gravel material, waterlogged soils and some turf inclusions. The surrounding ditch measured 2.94-4.9m in width and 0.84-1.7m in depth. The sequential relationship of the ditch to the mound is uncertain as it may have formed part of the original construction or a later elaboration. The ditch appears to have been key to the overall barrow design, with the iron staining in the basal fills suggesting the presence of periodic standing water. The ditch gradually infilled during the life of the barrow, with the fills tracking its various phases of use, modification and disuse. The fills contained evidence of discrete charcoal deposits reflecting the first early-middle Bronze Age cremation cemetery (Cemetery 1) placed into the south-west quadrant of the mound (cemeteries are discussed in greater detail in the next section). The recutting of the ditch appears to coincide with the development of the large middle Bronze Age cremation cemetery (Cemetery 2) situated across the eastern portion of the mound. Silting of this ditch continued during this period with some of the later burials cut into its upper fill, potentially signifying the final change in significance beyond its original barrow form. The barrow appears to have been a visible landscape feature into the Iron Age and potentially later, with a Roman cremation burial (Cremation Burial 16.103) placed at its eastern edge.

The siting of the barrow at West of Ouse over an earlier monument is a trend witnessed across the region with examples from Barnack (Donaldson et al. 1977) and Barleycroft/Over, Cambridgeshire (Yates 2007; Evans et al. 2016). The placement of barrows overlying earlier monuments may have created a link to place and past as opposed to strictly or only serving a funerary purpose (Garwood 2007, 46). There was no evidence that the West of Ouse barrow included a primary interment, with the lack of a central burial also noted at other sites including Roxton, Bedfordshire (Taylor et al. 1985), and in the Upper Severn Valley (Havard et al. 2017). The construction of barrows, associated with funerary activity or not, may have served as an expression of developing land tenure with monuments placed in visible locations, at boundaries or along routeways (Barrett 1989; 1990; Barrett et al. 1991; Johnston 2001). The series of small ring-ditch monuments at Conington discussed earlier in this chapter were located adjacent to field systems, displaying a strong link between boundaries and monuments. The barrow at West of Ouse, located on a ridge overlooking the River Great Ouse, is reminiscent of Barrow 17 at Over, Cambridgeshire. Barrow 17 measured c. 35m in diameter and comprised a central mound surrounded by a ring-ditch (Evans et al. 2016, 303). As at West of Ouse, the Over barrow displayed evidence for multiple phases of development, remaining a key landscape feature into later periods (Evans et al. 2016, 320). This was also evident at the large, c. 32m wide, barrow uncovered at Horseheath Road, Linton, where sherds of late Bronze Age pottery were recovered from the barrow ditch (Blackbourn 2021). The role of barrows in the later Bronze Age has been debated, with burial practices for this time arguably less well-understood than those of the earlier Bronze Age (Cooper 2016). The continued use of monuments such as barrows for depositing material and burying the dead may have allowed them to act as anchor points within a changing landscape (Brück 2019; 2000).

The placement of monuments following an initial phase of clearance, as observed at West of Ouse Monument 1, was also witnessed at River Great Ouse on the eastern side of the river. An unusual timber circle or henge was uncovered at River Great Ouse (TEA 20) composed of eight groups of five post-holes in an X-shaped arrangement surrounding an area c. 28m in diameter (Fig. 2.19; see artist's reconstruction in Fig. 2.20). A mix of both intrusive and residual pottery was recovered from the post-holes with one post-hole radiocarbon dated to 1870-1620 cal BC (SUERC-85548). The monument is comparable to the late Neolithic-early Bronze Age timber circles of the Thames Valley including at Gravelly Guy (Lambrick and Allen 2004), Spring Road, Abingdon (Allen and Kamash 2008), and Cotswold Community (Powell et al. 2010). While no direct parallels have been identified, the Ouse Valley is known for a diversity of monumental forms and it may be that the River Great Ouse monument falls into this broad category. Monuments such as this may have acted as ceremonial gathering places located at the transition from the river valley to higher ground (Bradley 2007, 132). The pollen analysis from a series of nearby palaeochannels revealed that the timber circle would have been constructed within a landscape of extant woodland, with localised pastoral and arable activity. The use of timber to construct the henge may reflect its local environment, with tree-throws surrounding the monument highlighting the role of clearance in prehistoric place-making. Often overlooked, however, the presence of trees, and the transformation from woodland to thickets, would have equally impacted the experience and staging of the monument (Fyfe 2012; Davies et al. 2005). The monument showed no evidence for later remodelling or significance with the pattern observed elsewhere, and its citation by early and middle Bronze Age funerary activity was notably absent.

A large number of earlier to middle Bronze Age circular ditched monuments of varying form and function have been identified and excavated across Cambridgeshire and neighbouring regions (Cooper 2016, 9; Malim 2000). The interpretation of the large circular monument (Monument 200) uncovered at Brampton West exemplifies the difficulties in classification, being, uncomfortably, termed at various points of the project a henge, a ring-ditch, and a ploughed-out barrow (Figs 2.21 and 2.22). The monument's deceptively simple form masks a subtle developmental sequence and complex set of funerary practices. Monument 200 at Brampton West comprised an unbroken ring-ditch 3.5-5.2m wide and 1.2-1.4m deep enclosing an area 37.2m in diameter with a total external diameter of 45.5m. The ditch had a pronounced V-shaped profile with a distinctive step identified on the outside edge of the ditch. The sequence of ditch fills indicated gradual infilling, with charcoal from the basal fill radiocarbon dated to 1960-1770 cal BC (SUERC-85541). A similar date of 1890-1700 cal BC (SUERC-91540) was provided by the single un-urned cremation burial excavated within the northern quadrant of the monument. The placement of the cremation burial is reminiscent of the arrangement witnessed at the henge monument at Margetts Farm (Ingham and Oetgen 2016). The Margetts Farm monument was defined by a ring-ditch encircling an area measuring 26 × 23m with eight post-holes spaced 5.6-8.6m apart located around the inner circuit. A cremation burial placed within one of the northern post-holes was radiocarbon dated to 2020-1770 cal BC (Ua-40865). A thin black mineral layer within the henge interior was interpreted as potential evidence for the presence of a mound, indicating the development of the henge into a barrow at some point during its lifespan (Ingham and Oetgen 2016, 11). At Brampton West, several pits and post-holes were identified across the interior that did not form a coherent pattern and may not be contemporary, and no evidence of a positive mound was recognised prior to excavation. The presence of a mound at Brampton West is debatable, with the search for this potentially overshadowing the significance of the ditch.

The focus of funerary activity throughout the life of the monument, beyond the early cremation, is the deep steep-sided ditch. The initial infilling of the ditch appears to have resulted from the erosion of the ditch edges, with a Bronze Age bronze double-edged knife with a riveted tang recovered from the basal fill. The secondary phase of development is marked by the gradual infilling of the ditch into which two inhumation burials, an adult male and a sub-adult, were cut in the middle Bronze Age. The adult male (Burial 12.7), aged 26-35 with an estimated stature of 167.6cm, was placed in a crouched position with the legs tightly flexed in a grave on the south-eastern side of the monument (Fig. 2.23). The radiocarbon dating of the skeleton provided a date of 1540-1410 cal BC (SUERC-75948) with isotope analysis suggesting the individual was raised locally. An infant, aged c. 5 months, was buried in a similar stratigraphic position on the western side of the monument and radiocarbon dated to 1420-1260 cal BC (SUERC-91534), placing both burials within the middle Bronze Age. A shale armlet fragment with a perforated terminal was recovered from the final phase of infilling; this may be of Bronze Age date, although Iron Age and Roman examples are also known. The final funerary activity was the deposition of part of an adult right femur shaft in a pit that truncated the western side of the ditch. The ditch became the focus of funerary activity, with the artefacts deposited through the fills, but not within a grave, considered to function as grave goods. The deposition of artefacts is a key tenet of the earlier Bronze Age, with 'grave goods' expressing relationships between people, objects and places (Cooper et al. 2022, 50). In the case of Brampton West, this demonstrates a lasting relationship with the date from the basal fill of the ring-ditch providing a terminus ante quem for the construction of the monument in the earlier Bronze Age, with funerary activity beginning early in the life of the monument, even if this was not its primary purpose.