Cite this as: West, E., Christie, C., Moretti, D, Scholma-Mason, O. and Smith, A. 2024 A Route Well Travelled. The Archaeology of the A14 Huntingdon to Cambridge Road Improvement Scheme, Internet Archaeology 67 (Monograph 32). https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.22

Of all of the periods represented by the archaeology of the A14, it was the first four centuries AD that witnessed among the most intense human activity across most of the landscapes, from the gravel terraces and floodplain of the River Great Ouse in the west to the claylands in the east. This was a well-exploited and populated rural landscape, much of it book-ended between two larger nucleated settlements or 'small towns' at Godmanchester and Cambridge. Although there was demonstrable continuity from the late Iron Age in many sites, there were also significant developments over this period, much of which was directly or indirectly stimulated by the land's incorporation into the Roman state. This chapter will explore these developments through examinations of the physical evidence for settlements, buildings and landscapes, and an assessment of the varied socio-economic and ritual activities evidenced at the A14 sites over time.

Use top bar to navigate between chapters

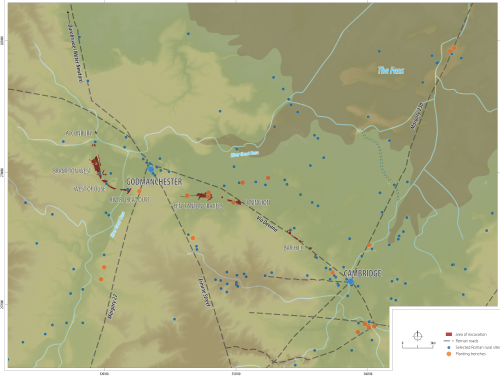

A total of 13 settlements dating to the Roman period were identified across the A14 (Fig. 4.1). The majority of these can be classified as 'complex farmsteads' comprising systems of conjoined enclosures or a single intensively sub-divided enclosure (Allen and Smith 2016, 28). Alongside these, elements of a probable villa complex and two possible nucleated settlements were recorded. A summary of these settlements is provided within Table 4.1 (along with references to the relevant online reports).

At the western end of the A14 seven Roman period settlements were identified (Figs 4.1 and 4.2). The northernmost, Alconbury 4, comprised a series of rectilinear enclosures, defining the periphery of a probable nucleated settlement. The complex farmstead at Alconbury 3 to the south consisted of a series of sub-divided enclosures. At Brampton West, to the south of Alconbury, two complex farmsteads were recorded. The northernmost, Brampton West 100, encompassed two areas of activity, with evidence for pottery production in both. Brampton West 201, located towards the southern end of the Landscape Block, comprised two distinct phases of activity. In the early Roman period, the farmstead consisted of a series of pottery kilns and a small enclosure. In the 2nd century AD a 'new' farmstead was established to the south of the kilns.

The complex farmstead at West of Ouse 3, to the south of Brampton West, comprised a series of enclosures, trackways, and several pottery kilns. Located to the south-east, activity at West of Ouse 4 was centred upon a further group of pottery kilns. Following the disuse of the kilns around the mid-2nd century AD, both settlements were focused on agricultural production, before falling out of use around the later 3rd century AD. Activity at West of Ouse 4 was probably closely related to developments on the eastern side of the river at River Great Ouse 2. Here an early Roman farmstead was recorded alongside a series of planting trenches. This expanded into a larger complex farmstead in the 2nd century AD and during the later Roman period the farmstead was redeveloped into a villa, although only the periphery of this was excavated.

Within the centre of the A14 corridor three Roman settlements were identified at Fenstanton Gravels. Fenstanton Gravels 4 appeared to form the focus of activity, with Fenstanton Gravels 3 and 5 possibly operating as 'satellite' settlements. The latter were both associated with a series of planting trenches. The periphery of a possible roadside settlement was recorded at Conington 4, to the east of Fenstanton Gravels. The early phases of the settlement were associated with an enclosure system and several blocks of planting trenches.

At the eastern end of the A14 scheme a complex farmstead was recorded at Bar Hill 5. This comprised a sequence of enclosures associated with pastoral farming. Further agricultural activity associated with this settlement was recorded in TEA 37. Bar Hill 2 lay at the easternmost extent and comprised the remains of an enclosed farmstead, defined by a single sub-divided enclosure.

The A14 settlements are situated within a wider Roman landscape that was characterised as part of the Cambridgeshire Fen Edge Case Study in the University of Reading's Roman Rural Settlement Project, which formed part of a wider overview of the Central Belt region, extending from South Wales to Cambridgeshire (Smith 2016a, fig. 5.1). A total of 72 farmsteads, four villas, nine nucleated settlements, five pottery production sites, two religious sites and twelve field systems were recorded within this Case Study area (Smith 2016a, 193). Among the nucleated settlements are the Roman 'small towns' at Cambridge (Duroliponte) and Godmanchester (Durovigutum), which, as noted above, lie towards the eastern and western ends of the A14 scheme (Figs 4.1 and 4.3). These 'small towns' were connected to each other by the Via Devana Roman road (Margary 24), which was probably set out in the mid/third quarter of the 1st century AD and connected Colchester to Chester (Evans and Ten Harkel 2010, 36). Roman Cambridge developed from an extensive late Iron Age settlement (Alexander and Pullinger 2000), whereas the earliest activity at Godmanchester has been suggested as the remains of two possible Claudian/Neronian 'forts' (Green and Malim 2017, 63), though the existence of these 'forts' is not substantiated by the evidence (Millett 2019, 759). The site developed into a 'small town' from the later 1st century AD, reaching its height during the 2nd century AD, with a possible mansio and bathhouse (Smith and Fulford 2019; Jones 2003; for critique of the mansio see Millett 2019). Branching off from Godmanchester is a second road extending in a south-westerly direction towards Sandy (Margary 22), passing through the eastern extent of the River Great Ouse 2 (Fig. 4.3). Excavations across the road suggest it was set out in the 1st century AD (see MCB17569) (Green and Malim 2017, 65). Both the Via Devana and the Sandy road intersect with Ermine Street (Margary 2b), extending from London, through Godmanchester and the settlement at Water Newton (Durobrivae), to York.

Since the publication of the Cambridgeshire Fen Edge Case Study, archaeological investigations have been advanced on a number of important Iron Age and Roman sites in the vicinity of the A14. This includes excavations at Northstowe (Aldred and Collins forthcoming), North-West Cambridge (Evans and Lucas 2020; Brittain and Evans 2019), and at Dairy Crest and Cambridge Road, Fenstanton (Ingham 2022). To the south of the A14, as part of the A428 Black Cat to Caxton Gibbet Improvement Scheme, a range of Iron Age and Roman farmsteads were recorded (Wright 2022). Although all of these sites are referenced within this chapter, a broader study of the Roman landscape around the A14 is reserved for a wider synthesis of the hinterlands of Godmanchester and Cambridge in the project's landscape monograph (West et al. forthcoming). This synthesis uses the much greater body of Roman sites known and recorded in the Cambridgeshire HER (as opposed to the sites mostly derived from the Roman Rural Settlement Project in Figure 4.3) that are beginning to redraw the nature of Roman rural settlement and important nodal settlements around Cambridge and Godmanchester.

By the time of the Roman Conquest a number of the Iron Age sites on the A14 had been abandoned (see Chapter 3), while others continued to be occupied up to and beyond the mid-1st century AD. This period was characterised not only by the initial invasion in AD 43, but the subsequent expansion of the Roman state and a series of revolts. Previous surveys of the period have frequently focused on the impact of these historical events and their definition within the archaeological record (Dawson 2000a, 108; Wallace 2016; Fulford and Brindle 2016). This has often resulted in change being explained through reference to known historical events, creating an artificial divide between the Iron Age and Roman period (Wallace 2016, 126), and comes at the expense of examining the poly-causal nature of change in the later 1st century BC to the 1st century AD, and its varied regional effects (Hill 2007; Creighton 2006). Instead, these historic events need to be understood within their local context, examining the data from a 'bottom up' rather than a 'top down' approach. In the following section, two strands of data are examined to explore the definition and nature of the post-Conquest period across the A14; the artefactual evidence, followed by a review of the sites themselves.

Archaeologically the definition of the Claudian/Neronian period is ambiguous, with artefact and radiocarbon date ranges extending either side of AD 43 (see relevant radiocarbon dates in Table 4.2). The following is a brief summary of the main datable artefacts of this period recovered from across the A14 scheme. Further details are found in the relevant specialist overviews.

| Settlement | Feature | Sample | Material Dated | Labcode | δ13C relative to VPDB | Radiocarbon Age BP | Radiocarbon Date (95.4% Probability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brampton West 100 | Inhumation Burial 10.192 | 107389 | Human Bone: - | SUERC-91524 (GU53800) | -20.2 | 1987±26 | 50 cal BC - cal AD 120 |

| Brampton West 100 | Inhumation Burial 10.198 | 107297 | Human Bone: - | SUERC-91525 (GU53801) | -19.9 | 1985±26 | 50 cal BC - cal AD 120 |

| Brampton West 100 | Ditch 7A.184 | 72172 | Animal bone- Skull: Cattle | SUERC-98139 (GU57546) | -22.8 | 1976±28 | 50 cal BC - cal AD 130 |

| West of Ouse 3 | Kiln 14.269 | 14508 | Charred Cereal grains: Triticum sp. | SUERC-91376 (GU53714) | -22.8 | 1971±25 | 40 cal BC - cal AD 120 |

| Fenstanton Gravels 4 | Ditch 28.263 | 28452 | Charred Cereal grains: Triticum spelta | SUERC-91387 (GU53722) | 2029±25 | 100 cal BC - cal AD 70 | |

| Fenstanton Gravels 4 | Pit 283579 | 28594 | Cereal: Triticum sp. | SUERC-91460 (GU53724) | 1973±24 | 40 cal BC - cal AD 120 | |

| Fenstanton Gravels 4 | Inhumation Burial 28.529 | - | Human bone: - | SUERC-97742 (GU57429) | -19.1 | 1983±25 | 50 cal BC - cal AD 120 |

| Conington 4 | Waterhole/Well 32.1 | 320947 | Animal Bone: red deer | SUERC-93232 (GU54663) | -22.2 | 2001±25 | 50 cal BC - cal AD 110 |

| Bar Hill 3 | Inhumation Burial 41.61 | - | Human bone: - | SUERC-85559 (GU50645) | - | 1971±24 | 40 cal BC - cal AD 120 |

| Bar Hill 5 | Inhumation Burial 38.318 | - | Human bone: - | SUERC-97751 (GU57438) | -20.1 | 2032±25 | 110 cal BC - cal AD 70 |

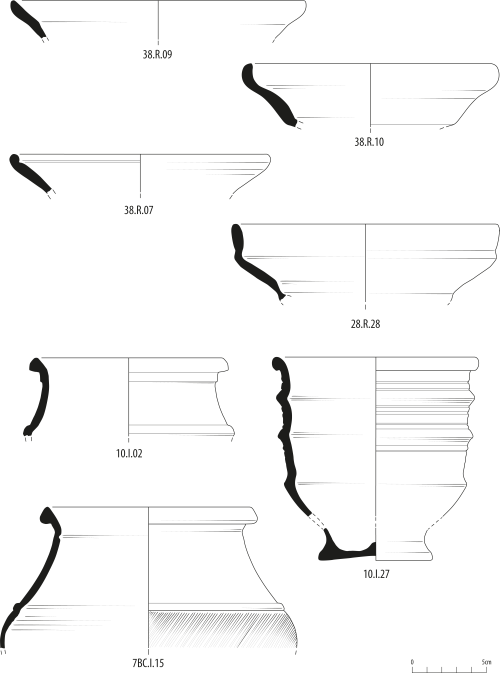

Much of the ceramic assemblage can be hard to date precisely and separating pre-Flavian and post-Flavian material is particularly difficult (Anderson and Brudenell 2010, 48). Aylesford-Swarling Wares continue to occur in varying quantities across the A14 into the mid- to late 1st century AD (Sutton et al. 2024), although there is an apparent decline from around the AD 60s (Lyons 2024). During this period Aylesford-Swarling Wares are found alongside vessels in the Gallo-Belgic 'tradition'. These appear in increasing quantities from c. 25 BC to AD 85, comprising both imported and locally made examples (Pitts 2017, 46). Locally produced Gallo-Belgic forms were recorded across the A14, with butt beakers being the principal form, alongside examples of platters and girth beakers (Lyons 2024; Sutton et al. 2024) (Fig. 4.4). At Fenstanton Gravels 4 and Bar Hill 5 these included copies of terra nigra plates, produced in the post-Conquest period, but remaining in use until c. AD 80. Given the persistence of these into the later 1st century AD, it is probable that some relate to the Flavian redevelopment of the settlements, rather than the Claudian/Neronian period.

At Brampton West, sherds of imported terra rubra, terra nigra and Lyon Ware were recovered. Alongside these, very small quantities of imported Gallo-Belgic white ware were recovered from across the A14. Other contemporary pottery includes a sherd of samian stamped by the potter PAESTOR, dating to c. AD 35-60 from Brampton West 100 (Monteil 2024b). Comparable examples have to date only been recorded at Colchester and Waddon Hill (Hartley and Dickinson 2011, 6). At several of the A14 sites, sherds of Claudio-Neronian samian were recovered, but these could have remained in use beyond the 1st century AD (Willis 1998; 2004).

From the fill of kiln 10.706 at Brampton West 102, fragments of an early-to-mid 1st century AD polychrome cast glass ribbed bowl (F10306) and three copper-alloy Colchester brooches (F10307, F10310 , F10352 ) were recovered (see Chapter 3). This vessel was imported from the Mediterranean, although whether this was done directly or through intermediaries is unclear. Evidence for pre-conquest glass in Britain is generally rare (Cool 2020), although glass fragments were noted from Iron Age contexts on the A14. The association of the bowl with three Colchester brooches suggest a votive deposit associated with the closing of the kiln.

Other brooch styles of this period include Aucissa and Hod Hill types (see the finds overview for wider discussion; Humphreys and Marshall 2024b). The latter may have been introduced to Britain by the Roman army and initially could have been popular in military communities (Mackreth 2011, 133-4, 142). However, they have a broader distribution, appearing in early civilian centres such as London (Perring and Pitts 2013), and may also have been adopted or manufactured in Romano-British rural communities (Harlow 2021). Hod Hill brooches occur in small quantities across the A14, with a notable concentration at Fenstanton Gravels 4. Here they appear to be associated with the Flavian development of the site (see below).

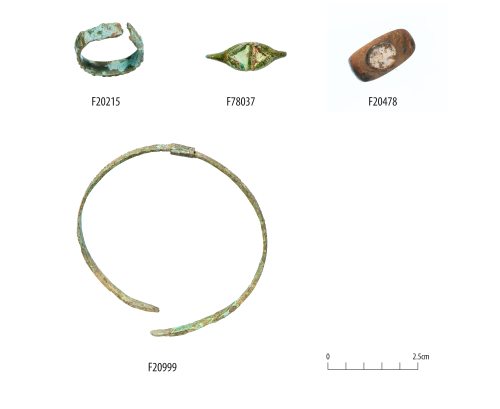

Probable Claudio-Neronian 'militaria' include two examples of penannular strip/cuff bracelets, one from Brampton West 100 (F72002 ) and the second from Bar Hill 5 (F38036 ). This form of bracelet (Cool 1983, IX) is sometimes argued to be a type of military award given to veterans of the Claudian campaigns, the distribution of which could reflect areas in which Claudian veterans were settled, with a particular focus within the territory of the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes (Crummy 2005, 93). Harlow , while seeing a military origin as plausible, suggests that the style could have been dispersed by military examples being passed down through families or by local copies/imitations (2021, 103-8, fig 49; Humphreys and Marshall 2024b).

A limited range of Claudio-Neronian coinage was recovered from across the A14 (Humphreys and Bowsher 2024). Among these were two Claudian copies, from Brampton West 100 (F72006 ) and Fenstanton Gravels 4 (F28104 ), which probably fill the gap in supply between the end of availability of regular Claudian issues and the arrival of Neronian issues (i.e. AD 54-64). While typically linked to the Roman army these copies would have been circulated beyond the immediate military sphere, with comparable copies previously recorded at Cambridge and Godmanchester (Kenyon 1992, 377). Alongside these Claudian copies four issues of Nero were recovered. Two of these were found in later 1st to 2nd century AD contexts at Fenstanton Gravels 4.

The artefactual evidence outlined above gives some degree of chronological framework to assess the nature of settlement development in the early post-Conquest period, although the resolution is still relatively poor so that whether some changes occurred prior to or after the Conquest remains uncertain. As discussed in Chapter 3, the late Iron Age was a period of significant settlement disruption across the A14 sites, with 14 of the 23 settlements (c. 61%) being abandoned or shifting location (Fig. 4.2). At six of these, this disruption appears to have occurred at the very end of the Iron Age or early in the post-Conquest period. These settlements comprise Brampton West 1, 2 and 102, West of Ouse 2, Fenstanton Gravels 1, and Bar Hill 3.

At Brampton West, there was limited evidence for activity in the Claudio-Neronian period, which marks a major shift from the expansive middle to late Iron Age settlement. Located at the northern end of the Landscape Block, Brampton West 1 appears to have been 'abandoned' before the mid-1st century AD, while Brampton West 2 nearby, which was only established in the late Iron Age, may have continued a little beyond the mid-1st century AD, albeit on a reduced scale. To the south at Brampton West 102, a similar pattern is recorded, with some of the late Iron Age enclosure ditches continuing to be infilled during the later 1st century AD (these sites are discussed in Chapter 3 and shown on Fig. 3.23). A kiln at this site (10.706) contained a finds assemblage of Conquest date as noted above, while a field boundary or drainage ditch to the west of the main settlement contained a copy of a coin of Claudius (F72006 ). Ultimately the area of this settlement seems to have become partly incorporated into the expansion of Brampton West 100 during the Flavian period (see below).

Elsewhere, the Iron Age settlement at West of Ouse 2 appears to have been abandoned prior to the mid-1st century AD, with activity shifting north-west to West of Ouse 3; although the nature of the earliest phases at the latter site are ambiguous, the evidence does point to it having been 'established' early post-Conquest. This would seem, therefore, to be a good example of settlement shift rather than abandonment, which may otherwise have been the interpretation had not such a wide area been investigated. At Fenstanton Gravels 1 an enclosed late Iron Age settlement also seems to have been 'abandoned' or to have shifted location prior to the Conquest period, while the settlement at Bar Hill 3 had some limited early Roman activity, including an inhumation burial, but nothing that suggests sustained occupation by this time.

Although significant numbers of settlements were apparently being abandoned or shifting in location at this time, it is clear that at least seven existing settlements continued in use through and beyond the Conquest period, albeit some of them seemingly at a reduced level (Table 4.1). The earliest phases of Alconbury 4 are somewhat ambiguous but it appears to start in the late Iron Age and certainly continues through into the later Roman period, probably in the form of a nucleated 'village' settlement as evidenced by the geophysical survey (see below). Alconbury 2, in contrast, which was abandoned earlier in the late Iron Age, was not reoccupied (as Alconbury 3) until the 2nd century AD, although its associated field system may have remained in use in the intervening period. The late Iron Age to early Roman settlement focus may have shifted to the north, as features of this date were recorded nearby at Weybridge Farm (HER 363694).

As noted above, at Brampton West there was relatively little activity at this time, though Brampton West 100 did continue and may have expanded somewhat. Activity at River Great Ouse 2 appears to have been significantly reduced during the latest Iron Age-earliest Roman period, though it was not abandoned and soon after developed into a larger and thriving complex farmstead and eventually into a villa complex. At Fenstanton Gravels 4, the middle-late Iron Age farmstead expanded during the latest Iron Age to earliest Roman period before undergoing extensive redevelopment during the Flavian period (see below). Fenstanton Gravels 3 and 4 also seem to have continued into the Roman period, though the chronological resolution of these sites is poor.

Bar Hill 5 was the only settlement in that landscape block to continue to be occupied into the early Roman period and beyond, with a sequence of short-lived enclosures dug in the early to mid-1st century AD, soon replaced by a rectilinear enclosure and multiple ditches, suggesting an expansion of activity perhaps following a period of contraction. The precise chronology of these features is uncertain, owing to truncation by later Roman enclosures. The persistence of Bar Hill 5 into the Roman period could in part be due to its proximity to, and associations with, the settlement at Northstowe, which was occupied into the later Roman period (Aldred and Collins forthcoming).

Overall, it is clear that the state of 'settlement flux' within the latest Iron Age and early post-Conquest period is at least in part a continuation of longer-term trends, coming on the back of the disruption witnessed in the earlier part of the late Iron Age discussed in Chapter 3. It accentuates a broader pattern of settlement upheaval (abandonment, establishment and transformation) at this time observed in the wider region within University of Reading's Roman Rural Settlement Project, (Smith 2016a, 196). The ambiguity around the dating of this period makes interpreting the causes and mechanisms behind these changes difficult. No doubt the arrival of the Roman army in the wider region and its subsequent activities in the mid-1st century AD had some impact on the local communities. This would, however, have been highly varied and potentially unique to individual communities (Mattingly 2006). In a number of cases the effects of this process may have been negative, with a loss of rights and land, though to what degree land was confiscated or reallocated is difficult to measure. It has been previously suggested that large parts of southern Britain may have been incorporated into imperial estates following the Boudican revolt (Perring 2013, 10), though there is little convincing evidence for this (J. Taylor 2000). Within the A14 sites there are signs in the Flavian period for some element of perhaps indirect state involvement, or at the very least for new owners and systems of land management. This could suggest a process of land consolidation during this time, reflecting on wider policy changes after the various military events of the mid-1st century AD (Salway 1993, 91), or much more indirectly, the reshuffling of local power structures as a result of the new circumstances of imperial impositions.

The A14 landscape witnessed continued dynamism throughout the Roman period, with major changes in settlement form and land management (a summary of the main settlement phases is presented in Table 4.3). As noted above there were a number of sites that displayed continuity of activity from the late Iron Age, though many were transformed and there were also new establishments, some of them located on or near to sites of earlier settlement (Fig. 4.2). There were three 'new' settlements established during the Flavian period (Brampton West 201, West of Ouse 4 and Conington 4), while many others, like Fenstanton Gravels 4 and River Great Ouse 2, were greatly expanded. This could indicate a form of early settlement consolidation, with population perhaps shifting from some of the farmsteads that were 'abandoned' during the Conquest period (discussed above). Significantly, there were no further 'abandonments' at this time. This was part of a wider reconfiguration of settlement and landscape seen across the region during the late 1st to early 2nd century AD (Taylor 2007, 110; Smith 2016a), perhaps in part reflecting changes in function and land rights/ownership, including the emergence of systems of tenancy and estates (Kehoe 2007).

| Settlement | Early to mid-Roman | Later Roman | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Roman | Mid-Roman | ||

| c. AD 70-150 | c. AD 150-250 | c. AD 250-410 | |

| Alconbury 4 | Single enclosure on periphery of probable nucleated settlement. Out of use by early to mid-2nd century AD | Nothing within the excavated areas of this date but core of settlement presumed to continue | New' elements of the presumed nucleated settlement comprising 'ladder' enclosure system. Located to the south of the earlier Roman settlement features |

| Alconbury 3 | A 'new' farmstead on location of earlier Iron Age site. Series of ladder enclosures. | Continued use of space, activity centred on a series of ditched enclosures. General decline in level of activity. Final phase marked by a dark earth deposit. | |

| Brampton West 100 | Development of complex farmstead with two clearly defined areas of activity. Associated with LOV kilns. Possibly contemporary field system to north in area of earlier settlement (Brampton West 2). Funerary activity to the south. | LOV kilns out of use. Majority of earlier features still in use, except for those in southern area, which appear to fall out of use. | Continued activity, process of organic development and reuse of southern area. Late Roman pottery production. |

| Brampton West 201 | New complex farmstead associated with trackway and sequence of LOV kilns | Abandonment' of earlier settlement, new complex farmstead to the south. | Continued activity within southern settlement focus. Possible continuity into the 5th century AD. |

| West of Ouse 3 | Development and expansion of complex farmstead, associated with trackways and field systems. Evidence for LOV pottery production. | Pottery production ceases, extension of settlement boundaries and trackways. Earlier system of small enclosures replaced by larger fields. Farmstead in decline from early to mid-3rd century AD, no evidence for sustained activity into later Roman period. | |

| West of Ouse 4 | New complex farmstead associated with LOV kilns. | Decline of kilns, redefinition of enclosures. No evidence for sustained activity into later Roman period. | |

| River Great Ouse 2 | Evidence for limited agricultural and small scale settlement activity preceding redevelopment of site, which partially reused the earlier ditches. | Increase in activity - development of larger complex farmstead | Radical redvelopment as probable villa complex |

| Fenstanton 4 | New gridded system and series of trackways. Associated with series of buildings. Associated with four blocks of planting trenches and 'satellite' farmsteads at Fenstanton 3 and 5. | New system of enclosure set out possibly early to mid second century AD. Trackways from early phase still in use. Series of aisled buildings. | Slight contraction in settlement, earlier system of enclosures replaced by less formalised series of enclosures. Small cemetery. |

| Fenstanton 3 | Possibly planting trenches and other agricultural features, connected to Fenstanton 4. Full extent of settlement not excavated. | Uncertain levels of activity - possibly forming part of wider agricultural hinterland of Fenstanton 4. | |

| Fenstanton 5 | Series of planting trenches, connected to Fenstanton 4 via trackways. Full extent of settlement not excavated. | Probable continued activity into mid-2nd century AD, but planting trenches out of use. Area forming part of wider agricultural hinterland associated with Fenstanton 4. | |

| Conington 4 | Possibly earlier agricultural features, site redeveloped with setting out of system of planting trenches. Setting out of settlement - possibly part of larger roadside settlement to the north. | Continuity with earlier settlement | Increase in activity with setting out of large subdivided enclosure. |

| Bar Hill 5 | Redevelopment of site in late first century, sequence of three enclosures, with Enclosure 10 representing earliest. Subsequent redevelopment around Enclosure 12 and 18. | Modifications to enclosures, including redefinition of Enclosure 18, split into two part Enclosure 16. | Limited activity during period, farmstead in use until mid to late third century. Establishment of small cemetery. |

| Bar Hill 2 | Enclosed farmstead established around mid- to late 2nd century AD. At least two phases of activity, with second representing modifications to enclosure around the 3rd century AD. Settlement in use until end of 3rd century AD. | ||

During the 2nd century AD new farmsteads were established at Bar Hill 2 and Alconbury 3 while there was a small settlement 'shift' at Brampton West 201; the first two settlements were placed in areas that had been 'abandoned' since the earlier part of the late Iron Age, though there are some indications that agricultural practices had persisted (Table 4.3). Alongside this a number of existing sites were further redeveloped, including West of Ouse 3 and Fenstanton Gravels 4. These changes coincide with the expansion in activity at Godmanchester and Cambridge, along with evidence for increasing settlement nucleation in the Fen Edge in the 2nd century AD (Smith 2016a, 197). There is evidence for another period of 'settlement flux' during the later Roman period, with a number of sites being abandoned. This may have been part of a further phase of settlement consolidation, with the earlier complex farmstead at River Great Ouse 2 developing into a probable villa at this time, while at Alconbury 4 a new 'ladder' enclosure system was set out on the southern edge of the presumed nucleated settlement, possibly indicating an overall expansion of the occupation area.

In the following section, the development of these settlements during the early to mid- and late Roman periods is reviewed in a little more detail, though the full stratigraphic description and discussion by phase can be found within the individual Landscape Block reports. The transition into the 5th century AD is considered more fully in the next chapter.

At the north-western end of the scheme, Alconbury exhibits evidence for both continuity and discontinuity during the early Roman period (Fig. 4.5). The early enclosures excavated at Alconbury 4 continued until the early to mid-2nd century AD, but their apparent abandonment at this time probably represents nothing more than the shifting of activity on the periphery of the settlement, with the main core of the presumed nucleated settlement recorded on the geophysical survey just to the south and possibly in the extensive series of cropmark sites known to the east (e.g. CHER 00823).

Alconbury 3 appears to have been founded de novo in the 2nd century AD, and its location c. 0.5km to the south of Alconbury 4 suggests it may have acted as a 'satellite' farmstead to that settlement (Fig. 4.1). At least three phases of enclosure were recorded at Alconbury 3, with it being at its most expansive in the middle phase, dating approximately to the later 2nd-early 3rd century AD (Fig. 4.6).

At the northern end of the Brampton West Landscape Block in TEA 7B/C, there was evidence for the area being used for arable cultivation after the late Iron Age settlements fell out of use. Associated with these fields was a small barn. To the south, the existing farmstead at Brampton West 100 expanded during the mid- to late 1st century AD, with two zones of activity (Fig. 4.7). The northern half was defined by a trackway, which was initially associated with a series of 'roadside' plots, although these were relatively short lived, being succeeded by a larger enclosure (Enclosure 100). Within this area was a rectilinear post-built building (Structure 7A.192) and three Lower Ouse Valley (LOV) pottery kilns (see Pottery production). There were further reconfigurations of enclosures during the 2nd century, while the trackway across the northern edge continued in use into the later Roman period (Table 4.3). The southern zone of activity in this settlement was defined by a substantial boundary ditch (LB104). To the north of this boundary were ten LOV pottery kilns, one substantial building (Structure 7A.131) and other structural elements, while to the south was a small cemetery (Cemetery 100) with three inhumation burials, at least two dating to the earlier Roman period (see Funerary practice). Further to the south of the settlement were two additional early late Iron Age or Roman inhumation burials (10.198 and 10.192). It appears that activity within this area, unlike the northern zone, did not persist beyond the end of the 2nd century AD, which could be related to the disuse of the pottery kilns.

Located c. 0.6km to the south-east, Brampton West 201 was newly established probably in the later 1st century AD (Fig. 4.8). The first phase of this site comprised an east to west trackway with a single enclosure (204) to the south. Within this area were six LOV pottery kilns, with a second group of seven kilns being recorded 0.2km to the south-west. It is unclear if these represent contemporary or separate phases of pottery production. These kilns are broadly contemporary with a group of eight kilns located c. 1km to the south-east at RAF Brampton (Nicholls 2016; Sutton and Hudak 2024b). In the mid-2nd century AD a 'new' settlement nucleus developed to the south of the kilns. This comprised a rectilinear enclosure (Enclosure 203) with a strong domestic focus, reflected in the estimated mean finds densities (Table 4.1).

West of Ouse 3 seems to have been established in the mid-1st century AD, though as noted above there is a degree of ambiguity over the precise date of its foundation. However, it is clear that it developed rapidly in the later 1st century AD into a series of enclosures and small ladder-like fields, extending across an area greater than 11 ha and defined to the north by a trackway (Fig. 4.9). Associated with the early phases of the enclosures were three LOV kilns. Following the disuse of the kilns in the mid-2nd century AD, the enclosures were reorganised, possibly representing a shift in the site's economy.

Broadly contemporary with West of Ouse 3, though probably established slightly later, a second nucleus of activity was recorded at West of Ouse 4, c. 1km to the south-east (Fig. 4.5). The principal feature of West of Ouse 4 comprised a group of six LOV kilns. The proximity of the kilns to the River Great Ouse suggests they were located to take advantage of the river both in terms of water for pottery production and in moving goods across the region (see Integrated economies) (see Fig. 4.3). The kilns probably fell out of use around the same time as those at West of Ouse 3 in the mid-2nd century AD. Both West of Ouse 3 and 4 appear to be in decline in the early to mid-3rd century AD, becoming abandoned by the end of that century (Table 4.3).

The existing small farm and field system at River Great Ouse 2, on the other side of the river to West of Ouse 4, had been greatly extended by end of the 1st century AD (Fig. 4.10). The core of the settlement comprised a series of trackways, field systems and a possible ladder arrangement of enclosures, though much of this was truncated by later features. Within these was a group of five possible pottery kilns. A large area of planting trenches, probably contemporary with this phase of redevelopment, was developed on either side of the Roman road to Sandy, and located c. 1km to the east of the farmstead. The farmstead further expanded during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, corresponding with an apparent increase in the scale of arable cultivation (Turner and Roberts 2024). By this point the kilns and planting trenches had fallen out of use, though there was a more certain pottery kiln (20.228) found to the south of the site. Also associated with this phase of activity were two timber structures, including 20.100, which continued from the mid- to late Roman period, and two burials, one of which (20.507) had exotic ancestry (see Population).

At Fenstanton Gravels 4, lying c. 8km to the east of River Great Ouse 2, there was a similar expansion of settlement during the late 1st century AD, which also involved a major episode of replanning with the setting out of a system of trackways, rectilinear enclosures, and field systems (Fig. 4.11). The enclosures contained a number of post-built structures. At around the same time a possible roadside settlement was established along the Via Devana road at Fenstanton, c. 1km to the north (Ingham 2022, 177) (Fig. 4.3). During the 2nd century AD there was a further expansion of Fenstanton Gravels 4, with a new system of enclosures set out on broadly the same alignment as the previous phase. A substantial aisled structure (28.480) was erected, while three other timber buildings nearby (28.474, 28.478 and 28.479) could possibly have started life at this time, though the dating evidence is ambiguous (see Structural remains). Painted wall plaster recovered from the later Roman ditch, just to the east of the buildings, could derive from one of these structures.

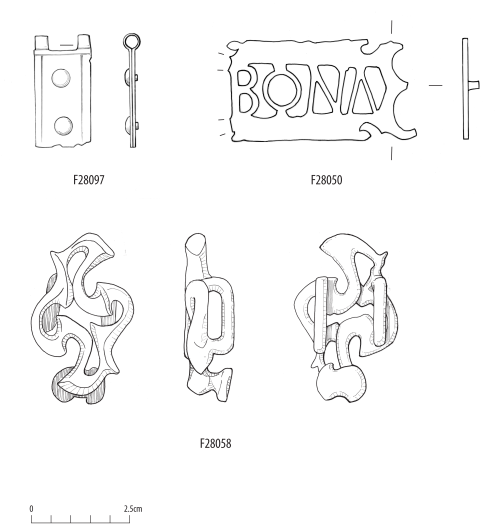

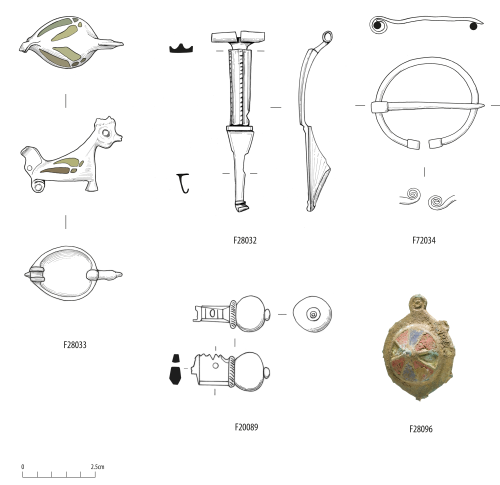

The overall size and organisation of Fenstanton Gravels 4 is atypical of most contemporary farmsteads from the region and suggests a potential specialised role, or at least that it had a larger, more diverse population engaged in a wider variety of economic activities. The presence of early Roman artefactual material such as samian imports, amphorae, and glass vessels in larger (although still limited) quantities compared with the other A14 sites reinforces this impression. A small number of military objects were also recovered from the farmstead, including a copper-alloy openwork military belt plate (F28050 ) with capital letters reading 'BONA', dating to the 2nd to 3rd century AD (Fig. 4.12; Table 4.4). A poorly preserved fragment of a shield boss (F28220 ) was recovered from a later Roman context, though the style of the shield boss could be earlier in date (Marshall and Humphries 2024). The presence of eight Hod Hill brooches and a single Bagendon brooch reinforces the impression of some form of at least indirect military link (Mackreth 2011, 133-4, 142; but see also Perring and Pitts 2013 and Artefacts of conquest above), although this material could have been distributed well beyond any military 'core' users, and doesn't necessarily indicate that there was an actual sustained military presence on site. A study of Roman weaponry and horse gear from non-military contexts in the Rhine Delta suggested they were brought home by ex-soldiers as personal memorabilia of their service (Nicolay 2007), while there could also be an economy trading in 'army surplus'. Whatever the exact status or function of Fenstanton 4, it is likely to have some connection with the possible roadside settlement recently excavated nearby at Fenstanton Dairy Crest and Cambridge Road (Ingham 2022) (see Integrated economies).

| Object | Small Find Number | Period | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'lorica segmentata' hinged fitting fragment | F28097 | 6.3 | Angular plate from one half of a strap hinge or hinged buckle; two rivets with domed heads on the central line; incised borders |

| Harness Fitting* | F28058 | 6.2 | Openwork trompetenmuster-style plate, comprising four conjoined double-ended trumpets; at one end there is a rivet on the reverse with an expanded foot. This may have attached a second strap or harness pendant |

| Mount | F28050 | 6.2 | Copper-alloy military belt plate fragment; flat openwork panel with plain parallel borders flanking openwork inscription with capital letters reading 'BONA'; 'B' end is broken flush with the letter; other end is also damaged but better preserved with part of an elaborate peltate-scroll terminal and retains an integral rivet shank with peened foot on the reverse. |

| Shield boss | F28220 | 6.4 | Sheet metal iron object, with a wide flat rim/flange and a domed central section; the overall shape is unclear due to its fragmentary condition, but the central dome appears round |

| Strap end^ | F27015 | Undated | Copper-alloy strap end fragment; plate-like; lower end is heart-shaped; beyond the heart the plate continues as a rectangular strip; long sides are partly scalloped and partly broken |

| Hackamore* | F78020 | 6.2 | Iron hackamore fragment?; iron bar, bent at a right angle, broken at both ends; integral loop on the outside of one arm near the bend |

Two 'satellite' farmsteads (Fenstanton Gravels 3 and 5) lay close to Fenstanton Gravels 4 and are likewise thought to have developed from Iron Age origins, though as neither were fully excavated this remains uncertain. Nevertheless, by the early Roman period they seem to have been linked to the larger Fenstanton Gravels 4 site via a system of trackways (Fig. 4.11) and may represent 'subsidiary' farmsteads. Associated with these settlements were a number of blocks of planting trenches dated loosely to the early Roman period (see Living off the Land).

At Conington, approximately 1km south-east of Fenstanton, a 'new' settlement was established during the later 1st century AD (Conington 4), though it seems only the southern fringes of this settlement were revealed within the excavation area. This earliest phase was marked by the setting out of an extensive series of planting trenches across the Landscape Block (Fig. 4.13), along with two enclosures and two trackways, which probably connected this part of the site to the main roadside settlement thought to lie along the Via Devana Roman road. This postulated settlement may have been part of the same roadside settlement as that excavated at Fenstanton to the west (Ingham 2022), although this would mean that this was spread out along the road for over 1.5km - similar scales are seen at certain other roadside settlements in Britain (e.g. in the Vale of Pickering; Powlesland et al. 2006). The layout at Conington persisted into the 2nd century AD. The presence of ceramic building material (CBM) and a large assemblage of architectural stone, including an undecorated altar fragment, a block of Alwalton/Drayton marble paving and part of a column, suggest the presence of a high-status building in the vicinity (see Structural remains). The nature of this building is uncertain but could either represent a wealthy dwelling or, more speculatively, in light of the altar fragment, a temple along the main road (see Ritual and Religion). The presence of the tops of two triangular or gabled Barnack tombstones suggest the presence of a formal roadside cemetery associated with this settlement (see Funerary practice). To the west of the site was an area of sand and gravel quarrying, which could relate to the construction of the trackways or the Via Devana, or to building works in the core of the roadside settlement. To the south-east of the Landscape Block two further areas of probable planting trenches were recorded during the trial trenching (Jeffrey 2016).

The Bar Hill 5 settlement, located towards the western end of the A14 development, underwent substantial redevelopment during the later 1st century AD, with the setting out of a new enclosure system associated with a number of trackways, probably used for the movement of livestock (Fig. 4.14). The changes coincide with an increased emphasis on pastoral farming. One enclosure (E12) formed the focus of domestic occupation, with evidence for several structures, while another (E16) may have been used for corralling livestock. During this period Bar Hill 5 may have functioned as a satellite farmstead to the nucleated settlement at Northstowe to the north (Fig. 4.3). During the early Roman period, a series of enclosures were established at this site that were organised around the junction of trackways. Two main zones were identified in this settlement, and between them was a substantial building and possibly a market space (Aldred and Collins forthcoming).

The most westerly settlement on the A14 was Bar Hill 2, which was established in the mid- to late 2nd century AD near to the earlier mid-late Iron Age Bar Hill 1, reflecting the general expansion of agriculture onto heavier clay soils in the early-mid-Roman period. The relatively small enclosed farmstead comprised two distinct phases of activity; the earliest comprised a rectilinear enclosure and boundary ditch (Fig. 4.5). The later phases of the site involved 3rd century AD modifications to the earlier enclosure.

The late Roman period saw the biggest shake-up of the landscape since the very late Iron Age-early post-conquest period, with a significant number of settlements contracting or falling out of use and a corresponding intensification of activity at other sites (Table 4.3; Fig. 4.2).

In the late 3rd century AD the Alconbury 3 settlement appears to have contracted, with activity centred on a series of small corrals, drainage ditches and waterholes, and with three inhumation burials located on the periphery (Fig. 4.16). Much of the excavated settlement was overlain by an extensive spread of finds-rich 'dark earth', most of which probably derived from manuring using occupation waste (MacPhail 2024a). This implies that this area may have seen a change from a pastoral to an arable focus by the 4th century AD, as also indicated by the presence of plough marks (see Arable farming). The deposit contained large quantities of late Roman pottery and several early medieval objects, hinting that some activity continued into the post-Roman period (see Chapter 5).

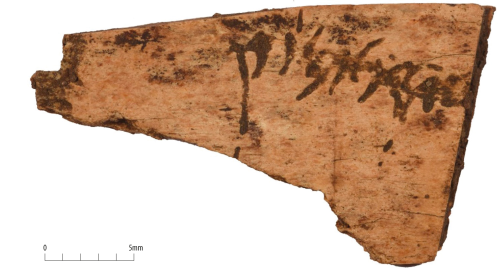

In contrast to the contraction at Alconbury 3, a new 'ladder' enclosure system was set out at Alconbury 4 in the late 3rd century AD, which persisted into the mid- to late 4th century AD (Fig. 4.16). The apparent expansion of Alconbury 4 at the expense of Alconbury 3 may have been prompted by increasingly wet ground conditions at the latter site, with the former site occupying a slightly more elevated position. The ladder enclosure system at Alconbury 4 (E1) was set out to the south of the concentrated area of settlement identified in the geophysical survey, and a substantial assemblage of bone-working waste was recovered within its southernmost plot. The majority of this relates to the manufacture of inlays and veneer, possibly connected to the manufacturing of items of furniture. Among the material was a fragment of bone with a cursive Latin inscription (F4083 ), hinting at a degree of literacy in the settlement, which does help corroborate its interpretation as a nucleated settlement (see such associations discussed in Smith et al. 2018, 70-6).

Further south in Brampton West, the two earlier Roman settlements continued in use into the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, albeit with some modifications. Pottery production resumed at Brampton West 100, with a group of four later Roman kilns discovered (Fig. 4.17) (see Pottery production), while a number of timber structures, quarry pits and inhumation burials also belong to this phase. Occupation at Brampton West 201 further south continued with some reconfiguration, which included a trackway, two probable corn-drying ovens and a small cemetery (Fig. 4.17). Elements of extensive landscape boundaries probably defining fields were also encountered at both settlements, hinting at an expansion of arable cultivation, which was also suggested by the corn-dryers. It is clear from the volume of material culture that both sites were intensively occupied during the late Roman period, though Brampton West 100 seems to have been abandoned prior to the end of the 4th century AD, while there was evidence for probable continuity in activity into the 5th century AD at Brampton West 201 (see Chapter 5).

The two settlements at West of Ouse (3 and 4) that were established during the earlier Roman period did not appear to continue into the 4th century AD, though late Roman field boundaries indicate the land was still being farmed. It is possible that this area became subsumed within an agricultural estate centred across the river at River Great Ouse 2, where the existing farmstead became transformed into a probable villa, defined by a large double-ditched enclosure surrounding an area over 7ha (Fig. 4.18). Comparable double-ditched villa enclosures are known elsewhere (e.g. Barton Court Farm, Oxfordshire; Miles 1986), with a local example revealed in recent excavations at War Fields to the north-west of Cambridge (Brittain and Evans 2019) (Fig. 4.3). The River Great Ouse enclosure was over double the size of these others, which may suggest a larger, perhaps higher status, complex. The presence of such enclosures could certainly be viewed as demarcating social status as well as serving to define, protect and oversee private property (Martins 2005, 92; Scott 1990, 168).

Associated with the River Great Ouse villa were a number of probable timber buildings, some associated with agricultural processing and storage and one outside the enclosure identified as a smithy. The presumed main villa building and associated bathhouse is thought to lie within the unexcavated central part of the enclosure, as suggested by an assemblage of high-status building material (see Structural remains; and reconstruction in Fig. 4.19). This echoes the arrangement at the War Fields villa, Cambridge, where the double-ditched enclosure contained a bathhouse and two developed aisled buildings (Brittain and Evans 2019). The proposed villa at River Great Ouse 2 is one of several known villas within the vicinity of Godmanchester, including Rectory Farm (Lyons 2019), Bob's Wood (Hinman 2003) and the probable villa at Huntingdon (Spoerry 2000, 36-7). Another possible villa has been suggested further east at Fen Drayton, to the north-east of the Fenstanton roadside settlement (Evans 2013, 474).

Unlike River Great Ouse 2, the extensive complex farmstead at Fenstanton Gravels 4 did not undergo any elaboration during the late Roman period, and in fact appeared to contract to some degree, with a slightly less 'formal' layout, although it is likely that the major routeways remained in use (Fig. 4.20). The presence of a substantial collection of painted wall plaster from one of the late Roman ditches could represent demolition material from an earlier Roman building located nearby, suggesting that these may have been demolished by the late 3rd century AD. Nevertheless, despite the apparent downturn there were still two aisled buildings that were probably in use at this time, and the pattern of late Roman coin loss at the site is more typical of urban sites, suggesting that Fenstanton Gravels 4 continued to play an important economic role (Humphreys and Bowsher 2024; see Integrated economies), perhaps associated with the nearby roadside settlement at Fenstanton (Ingham 2022). A small cemetery (Cemetery 4) within one of the earlier enclosures contained two burials radiocarbon dated to cal AD 260-540 (SUERC-97747) and cal AD 250-420 (SUERC-97760), suggesting possible activity into the 5th century AD (see Chapter 5). No definite later Roman features were recorded at Fenstanton Gravels 3 and 5, though the minimal archaeological investigation precludes any certainty, and the small number of 4th-century AD coins recovered from the former site does hint at some activity.

The settlement at Conington 4 saw an intensification of activity during the late Roman period, albeit still within the existing spatial framework (Fig. 4.21). The earlier planting trenches and enclosures were replaced with a large rectilinear enclosure, a post-built structure, and numerous pits, some of which were quarries. The presence of large quantities of finds indicates an increase in domestic occupation within this peripheral location, suggesting an overall expansion of the presumed roadside settlement. Among the finds were further fragments of architectural stone and roof tile, probably from high-status buildings nearer the roadside. A cluster of kilns or ovens was located to the north of the enclosure, and although the precise function of these is uncertain, it is possible that were related to cereal processing as drying ovens. This phase of activity appears to have ended towards the end of the 4th century AD, although there is some evidence for agricultural activities on the site continuing into the 5th century AD (see Chapter 5).

There is limited evidence for occupation at either Bar Hill settlement (2 and 5) continuing into the 4th century AD, although a small late Roman cemetery was inserted into the north-western corner of an earlier enclosure at Bar Hill 5 (Fig. 4.14). The placement of this cemetery seems to coincide with a general reduction in activity across the site. The larger settlement to the north at Northstowe witnessed a similar process of contraction at this time, although here there is evidence of continued activity into the 5th to 6th century AD (Aldred and Collins forthcoming). Given the interlinked nature of the two sites, this contraction may have been the cause of the decline at Bar Hill 5.

The overarching impression from the archaeological investigations along the A14 is that the late Roman landscape was characterised by a significant reduction in settlement numbers, but not necessarily any reduction in agricultural exploitation of the land. Indeed, there is evidence in the form of field boundaries, corn-drying ovens (albeit quite limited) and plough marks, as well as from the environmental evidence, that there was an increase in cereal cultivation at this time (see Living off the Land). In total six of the 13 settlements in use in the earlier Roman period did not last long or at all into the 4th century AD, while a further two underwent some form of contraction. In contrast, five settlements had their most intensive activity during this phase, two of these relating to probable nucleated settlements (Alconbury 4 and Conington 4) and another to a villa complex (River Great Ouse 2). This would suggest a degree of settlement consolidation, perhaps in part reflecting the formation of larger more centralised agricultural estates engaged in more extensive arable cultivation (Allen et al. 2017, 170-7).

The settlements discussed above contained 99 features interpreted as structures, ranging from post-built fences and enclosures to small agricultural buildings and larger aisled buildings (Table 4.5). A total of 38 structures can be defined as actual buildings, though many others remain uncertain. The nature of the recorded buildings and their appearance is reviewed in this section.

The various Roman-period structures from the A14 have been divided into several broad categories (Table 4.5), though in a number of cases later truncation or poor preservation has led to some ambiguity in classification. In particular it is possible that some of the single-space buildings represent truncated aisled or multi-space buildings; in the latter case any internal rooms could have been defined by light screens that have not survived.

Single-space buildings were common, accounting for 71% of those recorded. These also showed the greatest diversity in construction, size, and function, though aside from two roundhouses from the earliest phase of West of Ouse 3 and two others from Fenstanton Gravels 4, dating to around the mid-1st century AD, all structures were either rectilinear or of uncertain form. The majority of the single-space buildings were simple rectilinear or square structures, built using post-holes, beam slots or a combination of both. Post-built structures ranged in internal area from 1.56m² to 90m² and built, on average, with six posts. At the simplest level there were a small number of four-post structures, typically thought to be grain stores (Morris 1979), though also suggested as mills at Langdale Hale in Cambridgeshire (Evans 2013, 69). A single four-post structure (14.23) was noted near the early Roman roundhouse at West of Ouse 3, while a pair of them were associated with pottery kilns at Brampton West 201.

Alongside these a number of larger, complex single-spaced buildings were also recorded. A substantial two-phase building (7A.131) was recorded at Brampton West 100, the earliest phase comprising four parallel beam slots with a fifth perpendicular to the others, which could have had a raised platform similar to examples recorded at Camp Ground (Evans 2013, 258-61).This was replaced by a more amorphous structure defined by a metalled surface and five post-holes; samples from a series of associated pits suggested this was connected with crop-processing activities (Fig. 4.22). Another large building from Brampton West 100 (7A.171), interpreted as a barn though possibly domestic or at least incorporating a domestic element, was built using a single continuous beam slot, which would have held the baseplates onto which the timber frame of the building was set. At the eastern and western ends of the building substantial post-holes were recorded supporting the superstructure of the building, perhaps indicating an upper level. Within the interior were two pits containing large quantities of charcoal, though it was unclear if these are contemporary or relate to later activities associated with Pottery Kiln 7A.172. Two entranceways into the building were recorded in the southern and north-eastern side. The larger southern door was possibly the main route through which crops and other agricultural produce were brought in.

Across the A14 eight possible aisled buildings were recorded, alongside a number of indeterminate buildings that could represent further examples (Fig. 4.23). Aisled buildings are defined by a series of regularly spaced posts along the main axis and are generally considered to have been multifunctional, incorporating agricultural, industrial and domestic aspects and sometimes combining elements of these within the same structure (Smith 2016b, 67; Hingley 1989, 39-45). The proposed A14 aisled buildings do not have evidence for outer walls, though as these were not the primary load-bearing elements, they do not necessarily have to be ground-fast features that would show in the archaeological record; that at least some of the buildings may not be aisled is therefore possible. They date from the mid-2nd century AD with a peak during the later Roman period, this expansion reflecting a shift towards the spatial segregation of domestic and productive activities from the Flavian period onwards (J. Taylor 2001, 51). The majority of the buildings appear to have had some association with agricultural activities, including crop processing and storage, and, as noted by Perring, the exaggerated emphasis on the architecture of storage could have been a feature of estates where owners were infrequently resident and therefore less able to define and reinforce their social position through social activity alone (Perring 2002, 55). However, it is also likely that the larger buildings in particular incorporated social and domestic space; these would have been impressive buildings, and as recently commented by Wallace (2018, 252), they may have been used as 'a conscious method of communicating the owners'/inhabitants' inclusion in the land-owning rural peer group and served as a space for creating and reinforcing hierarchies and social relationships with kin, tenants and peers'.

The purported aisled buildings were all post-built structures with no obvious masonry components, with internal areas ranging between 60m² to 162m². In terms of distribution, most of the aisled buildings came from just two sites, five from the late Roman villa complex at River Great Ouse 2, and two from the complex farmstead at Fenstanton Gravels 4, with a possible third more ambiguous example (Structure 28.484) also from this site. There was also a single example from the probable roadside settlement at Conington 4 (33.145), dating to the late Roman period (see artist's reconstruction in Figure 4.24). At least one (28.480) of the Fenstanton Gravels examples was associated with the 2nd century AD phase of the site, with another (28.474) dated to the later Roman period, though it is possible that this and another building (28.478) were longer-lived buildings originally contemporary with the mid-Roman structure, defining a small complex of aisled and other buildings (see artist's reconstruction in Figure 4.25). A sizeable assemblage of painted wall plaster dumped in a nearby ditch could derive from one or more of these buildings, which would suggest that at least one may have had a 'domestic' function.

There are generally very few internal features within these buildings that may help determine function, although ovens were found in the interiors of three (28.474, 20.231, 20.233), which suggests at least parts of these buildings may have, as at Rectory Farm, functioned as drying sheds (Lyons 2019, 155-7). Structure 20.500 at River Great Ouse 2, located just to the north of the main villa enclosure, formed part of a probable smithy complex (see Fig. 4.34). This structure was associated with a metalled surface, overlain by a layer of clay with quantities of industrial waste, and a number of post-holes, suggesting a possible secondary structure. This could have taken the form of either a separate building or a lean-to, serving as a shelter over the primary area of metalworking. Structure 20.500 was constructed using elm posts, which is unusual in a Roman context. Elm, unlike oak, is prone to rot making it unsuitable for long-term constructions (Goodburn 2024e), and so the use of elm suggests that access to suitable oak during this period may have been limited or that the building was not intended to have a lengthy lifespan (see Woodland and fuel resources).

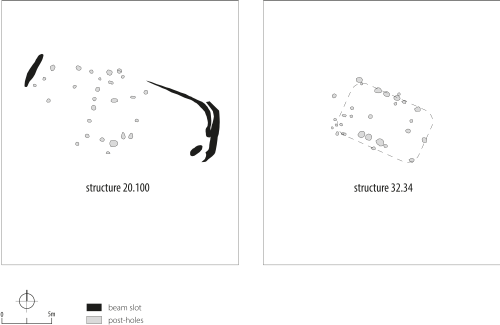

Only three certain examples of multi-spaced buildings were recorded, all defined by post-holes, some in combination with beam slots (Table 4.5; Fig. 4.26). The examples at Bar Hill 5 and Conington 4 (32.34) comprised two rooms, defined by a rear partition, with the Bar Hill building (38.180) appearing to be associated with crop processing or grain storage. At River Great Ouse 2 a possible two-roomed building with curved/bowed end walls (20.100) lay within an enclosure and spanned the mid- and late Roman periods (the transition from complex farmstead to villa). The layout of the enclosure recalls the form of the bowed end building recorded at Mucking in Essex, which was of similar dimensions (17.4 × 8.35m). The purpose of the Mucking building was uncertain but was suggested by the excavators to have had an administrative function, albeit on slim evidence (Lucy and Evans 2016, 97). A notable amount of domestic waste was recovered from the ditch surrounding the River Great Ouse building, indicating probable occupation.

In addition to these buildings a number of other timber structures were recorded on the A14 Roman settlements, including an example of a post-built enclosure at Bar Hill (38.202). At Conington 4 the remains of a late Iron Age to early Roman wattle fence were found in the west of the site and may have been used to section off a boggy area, while the recovery of fragmentary oak pales from Waterhole 14.85 at West of Ouse 3 provides further evidence of fencing (Goodburn 2024d). Wattle was also used in well linings, as seen at Conington 4 and at Brampton West 100 where elements of a late Roman plank box well were recorded. The box lining was 0.74m square internally and the corners were joined with simple alternating 'halving' joints and alternately driven iron nails with oak planks. Analysis of the timber indicates that low-quality timber was employed, suggesting that access to good-quality oak during this period might have been more constrained.

Where it could be discerned oak was the timber of choice across the A14 for constructing buildings, though, as noted above, in one case elm was used, possibly reflecting pressure on oak resources in the later Roman period (see Woodland and fuel resources). Walls were probably built using wood cladding or wattle and daub panels (Perring 2002, 88; Goodburn 1991). Willow was the principal wood exploited for these panels/fences, with several sites showing evidence for the management and use of willow. In other cases, it is possible that the walls were built using cob or other materials (Perring 2002; Rust 2006, 24). In general, the absence of substantial walls suggests that the weight of the roof in most buildings was supported by vertical posts supporting a tie beam with simple roof truss or common-rafter construction (Neal et al. 1990, 33). The space within this frame could have been used as an additional loft space for storage.

There is generally relatively little evidence for structural woodwork from the A14, with the notable exception of the elm posts. However, waterhole 28.600 at Fenstanton Gravels 4 contained key woodwork relating to construction, comprising a dividing wall of timbers set on end, 'stave wall' fashion (Goodburn 2024f). Other woodwork from the fills of this waterhole also provided evidence that structural woodworking, or at least timber conversion, was taking place in the near vicinity.

Although quantities of ceramic tegulae were recorded across the A14, it is probable that only a limited number of buildings had tiled roofs. At least some of the buildings associated with the River Great Ouse 2 villa were probably tiled, and there is also indication of tiled high-status buildings at Conington 4 and possibly at Fenstanton Gravels 4. The presence of small amounts of tegula and brick at most other sites could reflect material imported for a variety of uses, including as hardcore in ground consolidation (see Machin 2018, 289-90; 2024e). Instead, roofs may have been constructed using wooden shingles or thatch (Perring 2002, 120). The use of great-fen sedge (Cladium mariscus) as roofing material is noted at multiple Cambridgeshire sites (Fosberry 2021; see Stevens 1998), and seeds from great-fen sedge were noted in three kilns at Conington 4, where it was also used as a fuel (Fosberry 2024).

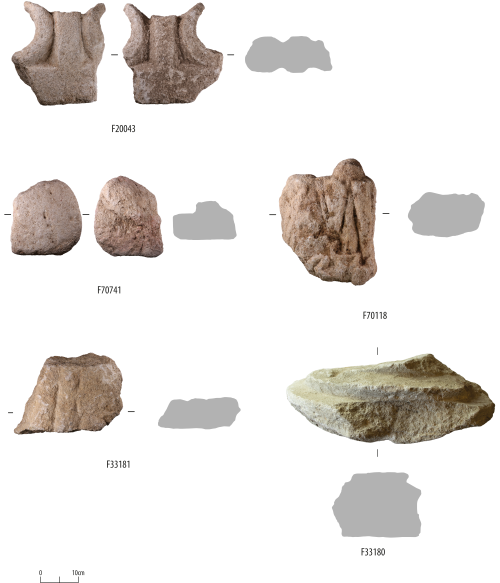

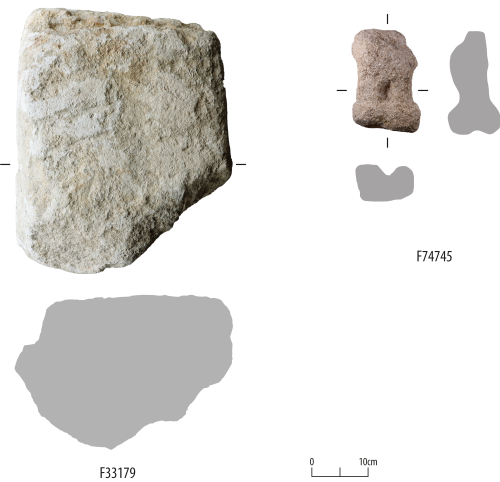

Evidence for stone buildings was limited, with no in situ stone walls or footings recorded. Nevertheless, there was evidence for more elaborate masonry buildings in the form of architectural fragments (Fig. 4.27). Sixteen fragments of architectural stone were recovered from River Great Ouse 2, including two elaborate elements of cresting from a roof of a large villa-type building, a plinth-shaped coping stone and various facing stones made of Barnack stone (Hayward 2024d). A miniature stone altar and base of a statue were also recovered from this site (see Ritual and Religion). An even larger stone assemblage of 37 fragments came from Conington 4, much of it dumped into a single large pit (Hayward 2024f). This included further examples of Barnack stone, such as a door pivot, the upper part of a plain altar, a Tuscan column base, part of a decorative cornice, and masonry blocks, along with probable Roman roofing stone, a marble paving stone and building rubble. A Barnack coping stone (for capping walls) was also recovered from Alconbury 3 (Hayward 2024a). Barnack stone was widely used for architectural elements across the region, with further examples recorded from Godmanchester (Green and Malim 2017, 97).

Evidence for architectural elaboration included c. 8.7kg of painted wall plaster from Fenstanton Gravels 4, which derived from at least two separate rooms (Machin 2024e). This was the only A14 settlement with substantial quantities of painted wall plaster, though a reasonable assemblage was also recovered from the recently excavated nucleated settlement at Northstowe suggesting the presence of a high-status building, possibly stone built, within the vicinity (Aldred and Collins forthcoming). Eight tesserae from a plain border were also recovered from Fenstanton Gravels 4, though it is uncertain if this derived from a building on site. Likewise, a total of thirteen golden yellow tesserae were recovered from the Alconbury 3 settlement during trial trenching but could not be clearly related to any buildings on the site and may have derived from the larger settlement at Alconbury 4 to the north (where further tesserae were found), as was probably the case with the Barnack coping stone (Jeffrey 2016; Hayward 2024a). Alternatively, the tesserae could have derived from the part of the site now buried beneath the A1M, levelled and ploughed in the latest Roman or more likely post/sub-Roman period. A few further tesserae were recovered from River Great Ouse. During the later Roman period a 'mosaic school' was probably in operation centred around Durobrivae to the north, to whom a wide number of mosaics across eastern England are attributed (Fincham 2004, 138).

Fragments of opus signinum, typically used in floor construction as well as aqueducts, cisterns and any buildings involving water, were recorded from four settlements, with almost 2kg recovered from River Great Ouse 2 (Machin 2024b). Also from this site were examples of opus spicatum, ridge tile, and box-flue tile, plus an assemblage of voussoirs was recovered from later Roman contexts. The latter are typically associated with bathhouses, suggesting the presence of such a structure at the villa. Further instances of these tiles were noted at Conington 4, suggesting the presence of a high-status building nearby.

Tentative evidence for possible lead piping was recovered in the form of lead waste recovered from the dark earth deposit at Alconbury 3. However, this could represent scrap brought to the site rather than direct evidence for a high-status building. Further fragments of lead were recovered from River Great Ouse 2. One fragment (F20084) could represent the remains of a lead pattern or the collection of waste from lead casting or plumbing.

At Alconbury 3 and 4 small numbers of iron fittings designed for use with wooden structures or pieces of furniture were recovered. At River Great Ouse 2 part of an iron window grille (F74018 ) was found alongside a fragment of window glass. A possible fragment of window glass (F32636 ) was also recovered from Conington 4. From across the A14 a limited number of large structural nails were recovered, suggesting that these may not have been widely used, although there were much greater numbers of smaller nails (Manning Type 1b), especially from late Roman contexts in River Great Ouse, probably used in cladding, roofing and shelving (Manby 2022, 62). Examples of woodworking tools included a complete iron mortice chisel (F28138 ) from Fenstanton Gravels 4 and a range of chisels and drill bits from River Great Ouse 2. Most notable from River Great Ouse 2 was an iron froe (F70300), which is the first example of its type found in Roman contexts in Britain. Modern froes are typically used to split timbers, but Roman examples may have been for a variety of uses, from the manufacture of fence staves to writing tablets. From the same site a possible iron trowel (F78608) may have been used in masonry construction or wall plaster (Humphreys 2024a). Other items that could be related to buildings include several examples of padlocks and/or padlock keys, which could have been used to secure doors and/or gates (see Humphreys and Marshall 2024b for more details).

Overall, it is clear that a reasonably wide variety of building types and forms were present within the A14 Roman settlements, though the highest status masonry buildings lay outside of the excavation areas - notably the probable villa buildings at River Great Ouse and roadside buildings at Conington. Other high-status building material may have been recycled over greater distances. The remaining structures were largely utilitarian timber buildings of varying scales and levels of embellishment. At the upper end of this were the mid- to late Roman aisled buildings at Fenstanton Gravels 4, which may have been quite well appointed, though for the most part the buildings seem to have been relatively simple single-room structures. Of course, it is likely that further buildings existed on many sites that have simply left no trace in the archaeological record, being constructed with mass-walling techniques, as was probably the case across many Roman rural settlements across Britain (Smith 2016b, 44).

Agriculture was central to the lives and overall economy of those living in the farmsteads excavated along the A14 corridor. This provided the necessary basics for living, as well potentially generating surplus, which could be traded for other items and/or used to feed the demands of the Roman state. In the following section, the nature of arable and pastoral farming within the A14 landscape is further discussed. The first part explores the evidence for arable cultivation, examining the way farmsteads were laid out, the range of crops grown, and the various processes involved. The second half examines the nature of pastoral farming, looking at the range of livestock and the various exploitation strategies. The final section considers the role of wild resources, including the management of woodlands. Much of this draws upon the extensive programme of environmental analysis carried out for the project, which is particularly robust for the Roman period, including in the region of 65,000 cereal grains, 55,000 chaff remains and 34,000 animal bone fragments. A more detailed overview of the environmental evidence specifically is available elsewhere within the A14 archive (Wallace and Ewens 2024).

The scale of the A14 excavations has meant that the majority of the recorded Roman farmsteads were able to be examined within their wider agricultural landscape, reflecting areas directly or indirectly exploited for arable cultivation and livestock husbandry. These were represented as either open space beyond the settlement limits or as field systems defined by ditches. At Alconbury 3, there is evidence for agricultural or perhaps horticultural activities taking place in small 'garden plots' or infields located within the enclosures (see Fig. 4.6). Most settlements appear to have operated a system of infields and outfields, with the infields representing areas of more intensive farming while outfields represent areas of lower intensity (Christiansen 1978). The location of these may have been informed by local soil conditions, with poor-quality ground being employed for pasture and high-yielding soils being reserved for arable cultivation. These distinctions were recognised by Columella who extolled the virtues of ground which was 'both rich and mellow' (De Rustica 2.2. 1-3; see White 1970, 89-91). The slight pastoral focus at Bar Hill 5 may represent a response to local soil conditions, while Roman settlements further to the west practised more mixed regimes on a diverse range of soil types (see below).

The size of the wider agricultural hinterland of each of the settlements is difficult to estimate. A subjective estimate of the catchment area of a Roman villa at Barton Court Farm in Oxfordshire (covering c. 1.2ha), suggested around 77ha for a mixed farm, which could be maintained by five working adults (Jones 1986, 41). This farm, it was suggested, could then support a herd of 35-50 cattle and a flock of up to 200 sheep, alongside a small area of 10-15ha producing cereals.

It is clear that there was a substantial variety in the scale of Roman settlement across the A14, which may provide some indication of relative population size and possibly the scale of associated landholdings, though this is by no means certain. Although at many sites there has not been enough of the settlement excavated to have any certainty, estimations of the size of the settlement core (i.e. excluding what would appear to be outer field boundaries) in Table 4.1 range from 1.2ha at sites like Brampton West 201 and Bar Hill 2 through to 8-9ha at Fenstanton Gravels 4 and River Great Ouse 2. If rural settlement size does have any bearing on associated landholdings it would then suggest that the fields and pasture of the latter settlements, a substantial complex farmstead and villa, would have encompassed large parts of the surrounding countryside, probably incorporating subsidiary settlements. At Fenstanton Gravels 4, this may have included the nearby farmsteads (3 and 5), though little is known about these smaller sites that aid in any understanding of their inter-relationships.

The extent of any fields associated with each settlement was probably defined by natural and manmade boundaries including rivers/ streams, ditches and hedgerows. The existence of hedgerows is widely attested within the botanical data, often being located close to enclosure ditches. Elements of the wider agricultural hinterlands - notably field ditches - were recorded in various places across the scheme, often some distance from any known settlement (e.g. at TEA 49, 0.5km north of River Great Ouse 2). These were generally poorly dated but do seem to be slightly more prevalent during the later Roman period, which correlates with the general picture of arable expansion suggested by the environment evidence, discussed below.

The majority of the farmsteads were associated with systems of trackways, facilitating the movement of people, animals, and goods to and from the site. These could, as suggested by Varro, represent public trails, allowing access to different zones of pasture (De Re Rustica 2.9). At Bar Hill 5 the system of trackways appears to be concerned with the movement of livestock into Enclosure 16 (Fig. 4.14), possibly to and from areas of pasture to the north and south. At Fenstanton Gravels 4 the network of trackways served to connect the site to the peripheral farmsteads at Fenstanton Gravels 3 and 5 (Fig. 4.11). A number of the excavated settlements were located in proximity to the Via Devana road between Cambridge and Godmanchester (Fig. 4.3), and it is likely that some of the smaller trackways connected to this or to the other main roads in the area. It is possible that the setting out of the road network provided a local stimulus for the expansion and foundation of farmsteads in the later 1st century AD, physically connecting the rural landscape to the emergent Roman state.

While the roads and trackways form the most visible aspect of the Roman infrastructure, the role of waterways within the region should also be considered. The River Great Ouse at the western end of the scheme runs close to a number of excavated settlements (Fig. 4.3), and it is probable that goods were moved via this waterway. The River Great Ouse runs northwards towards the peat Fens, passing by Earith to the coast. At Earith the extensive remains of a probable inland barge-port settlement was established at Camp Ground (Evans 2013). Goods could therefore have been moved via sites like Camp Ground and out towards the coast (see Movement of resources).