Cite this as: West, E., Christie, C., Moretti, D, Scholma-Mason, O. and Smith, A. 2024 A Route Well Travelled. The Archaeology of the A14 Huntingdon to Cambridge Road Improvement Scheme, Internet Archaeology 67 (Monograph 32). https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.22

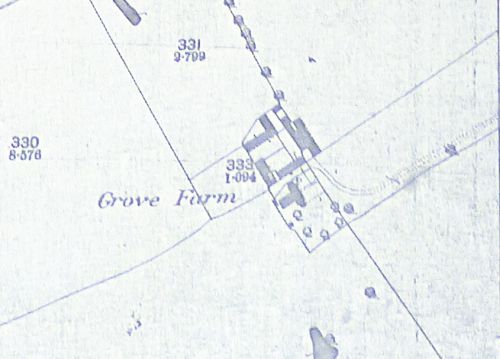

The archaeological excavations undertaken during the A14 improvement scheme identified medieval and post-medieval remains across the whole project area, the most important of which was represented by the abandoned medieval village of Houghton and the 19th-century Grove Farm, both located within Brampton West Landscape Block (Fig. 6.1). Full details of the Brampton West excavation can be found within the Landscape Block report (West et al. 2024).

Brampton West showed, to a certain extent, archaeological and historical continuity between the Saxon and Norman periods visible through the spatial relationship between the different settlements (Brampton West Settlements 3, 4 and 5), but also between the settlements and their field systems. Unfortunately, it is not possible from the archaeological evidence to ascertain whether the settlement shift between the two periods was caused by an overall reorganisation at one specific time, a gradual shift over a longer period, or was caused by a change in the farming population or their status. Agricultural and semi-industrial activities continued in the area during the post-medieval and modern periods.

The A14 scheme offered the opportunity to gain an understanding of settlements, landscape and land-use changes between the Saxon, medieval, post-medieval and modern periods, as well as the opportunity to understand the transition between these periods. Most of all, it has offered the ability to excavate the southern section of the medieval settlement in its near entirety.

This chapter will focus on the archaeological results at Brampton West, their setting within the A14 archaeological programme and the wider historical backdrop of the period from 1066 to the 20th century. The later medieval and post-medieval evidence in the remaining A14 landscape blocks, mainly represented by evidence of agricultural activities such as ridge-and-furrow cultivation and field boundaries, is shown in Table 6.1.

| Landscape Block | Medieval/Post-medieval evidence |

|---|---|

| Alconbury | Medieval plough furrows |

| Agricultural building (post-med) | |

| Brampton West | Deserted village (medieval) (Settlement 5) |

| Medieval plough furrows (Field system 4; 102) | |

| Medieval quarry pits | |

| Post-medieval quarry pits | |

| Post-medieval Grove Farm (Settlement 6) | |

| Post-medieval brick kilns | |

| Brampton South | Medieval ridge and furrow |

| Post-medieval quarry pits | |

| 19th-century field system (1) | |

| Post-medieval Trackway | |

| West of Ouse | Medieval plough furrows |

| Engraved medieval stone (SF15204) recovered from ridge and furrow | |

| Post-medieval field boundary ditches | |

| Post-medieval well | |

| Modern boundary ditches | |

| 19th-century brick culvert | |

| River Great Ouse | Medieval open field system associated with Offord Cluny |

| Plough furrows | |

| Two medieval Long Cross silver coins | |

| Post-medieval parish boundary between Godmanchester and Offord Cluny (gone by 1926) | |

| Post-medieval coins | |

| Post-medieval and modern field enclosures (gone by 1926) | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Medieval quarry pits |

| Medieval open-field systems | |

| Medieval plough furrows | |

| Medieval L-shaped ditch dividing the two field systems | |

| Medieval green glazed pottery | |

| Post-medieval waterhole/well | |

| Post-medieval trackways (4 and 6) | |

| Post-medieval enclosure | |

| Post-medieval quarry pits | |

| Post-medieval well | |

| 19th-century remains of a building | |

| Conington | Medieval plough furrows |

| Post-medieval double ditch boundary forming a potential trackway (Trackway 4) | |

| Quarry pits | |

| Bar Hill | Post-medieval plough furrows |

| Post-medieval coffin handle and human bone fragments | |

| 20th-century building foundations (Rhadegund Buildings) (MCB25200) |

Use top bar to navigate between chapters

Historically speaking, the A14 scheme would have fallen within the two 20th century counties of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire (the latter became a district of the former in the 1970s), although Huntingdonshire is the most relevant of the two. These two areas were first mentioned as separate geographical entities in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (late 9th century), where an entry stated that Huntingdon developed as a Saxon and Danish burh, favoured by its position on the lower ford over the River Great Ouse and along Ermine Street (Spoerry 2000, 37-39). Huntingdon prospered as a Danish military centre until Edward the Elder took it back from the Danes around AD 915, restoring and improving its fortification. A further section of the manuscript is dedicated to the Danish invasion of the south-east of England led by Thorskell the Tall in August 1009. After terrorising the east of the country in 1010, the Danish Army moved towards the west, but here '…Cambridgeshire firmly stood against them' whereas 'the East Anglians immediately fled' (Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, 1996 edn, 140). In Henry of Huntingdon's 'Historia Anglorum' (1080-1160) the two geographical entities are also described. In his Book 1 (chapter 5), where he describes the English counties and bishoprics, he stated that Cambridgeshire was the fifteenth county in the see of Ely whereas Huntingdonshire was, with others, subject to the see of Lincoln (Henry of Huntingdon Book 1:5 edn 1879). Despite the documentary evidence of the Saxon/Scandinavian period in this area, the archaeological evidence of this interface is practically non-existent here, as in some other parts of the country.

The aftermath of the Battle of Hastings (1066) and the succession of Duke William of Normandy to the English throne, saw several Saxon rebellions that arose from the discontent and resistance against the Norman conquerors across the country. One of the significant Saxon rebellions in Cambridgeshire was the Fenland Rebellion of 1071. The Fenland region, characterised by its marshy terrain, provided a natural stronghold for the rebels to mount resistance against the Normans. Hereward the Wake, a prominent Anglo-Saxon noble, emerged as a leader of this rebellion. He and his supporters carried out guerrilla warfare tactics from the Isle of Ely, launching attacks on Norman-held fortifications and estates. The siege of Ely (1070-1071) was perhaps the most remarkable event, which saw the Norman forces struggle to break through the natural marshy defences of the island. The Fenland Rebellion was not isolated, but it was part of a broader series of uprisings of which some were localised and short-lived while others lasted for years, continuing well into the following centuries, and ending ultimately with the displacement of the Anglo-Saxon ruling elite.

The Norman Conquest led to a profound transformation of the English socio-political landscape and saw the proliferation of fortification works across the country. These were characterised by castle construction probably to contain regional rebellions opposing Norman rule, but also the intensification of agricultural practices, the expansion of settlements, and the growth of towns.

The Great Anarchy of 1135-1154 represented a period of further political turmoil brought about by the rival claims to the throne of the Empress Matilda and King Stephen resulting in widespread chaos, civil unrest and socio-economic disruption. In Cambridgeshire, the personal rebellion of Geoffrey de Mandeville ultimately against both Matilda and Stephen caused further disruption. He sacked Cambridge, occupied Ely and from there plundered the fenland and fen edge communities, including Ramsey Abbey and St Ives (Creighton and Wright 2016), then using it as headquarters from where he carried on his plunder of the area, including Ramsey Abbey and St Ives. Despite this, the two counties flourished following that turmoil.

From the 11th to the 13th centuries, favoured by the medieval Warm Period (10th-13th centuries), England, like the rest of Europe, witnessed a period characterised by stability and economic growth that consequently saw rapid population growth. This, as well as the changes brought by the Norman Conquest, affected both Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire.

Not all Norman introductions benefited the population, and the implementation of the tallage (land use and tenure levied by kings), for example, caused much agitation. The people of Brampton and Houghton negotiated with the king, seeking protection from the increase in rents and services. When that was denied, they refused to pay and in 1242 and 1338 rebelled by recovering cattle seized by the authorities (Carpenter 2008).

During this period, the A14 scheme area was characterised by large swathes of agricultural land with intermittent villages and farmsteads, and with Cambridge and Huntingdon as well as St Ives and the port at Swavesey as the major centres of medieval settlement, trade, and industry. The economic expansion of Cambridge started with the corn trade and the grant by Henry I in 1131 (Roach 1959, 3). A further indication of the wealth of Cambridge was represented by the foundation of the university in 1209 and the foundation of churches by burgesses as well as the possible construction of St John's Hospital (c. 1200). By 1279, as stated in the Inquest carried out throughout the country by order of King Edward I, Cambridge had 17 parishes - three north of the river Cam and 14 south of the river - 17 churches, 76 shops or stalls, five granges, six granaries, three watermills, two windmills and a total of 535 messuages, an increase from the original 373 recorded in nine wards in 1086 (Rot. Hund. (Rec. Com.) ii, 356-40 cited in Roach 1959). The subsidiary roll of 1304 confirmed the continuous growth of Cambridge although by the mid-to-late 14th century and further during the 15th century, suggestions of economic stagnation and degradation started to appear in the form of the Black Death of 1349-1361, the Scottish and French War of 1318-1350, the Peasant Revolt of 1381, and two town fires in 1385.

Like Cambridge, by the 11th century, Huntingdon had become a significant settlement as stated in the Domesday Book entry of 1086 (Domesday Book, 1992 edition, 551). Excavations in Huntingdon have shown the expansion during the Saxon/Norman period (Mortimer 2007, 11-12; Mellor 2009) suggesting that urban occupation fully began in the 12th century and expanded with denser occupation in the 13th century. This period was characterised by open fields in the south-east, south of the Ouse Walk, and in the south-west at Mill Common. At Mill Common, 11th to 13th-century pottery production, gravel and clay extraction alongside agricultural activity within small burgage plots, was identified in recent A14-related excavations (Scholma-Mason et al. 2024).

Huntingdon, like Cambridge and the rest of England in this period, saw population growth and increased prosperity (Kenney 2003, 8). At this time, Huntingdon's status as a 'Shire' town, its position on the crossing of the river and along Ermine Street, and the tolls collected for travellers to the St Ives fair, one of the largest gatherings in the country, contributed to its success. The historical sources attributed to Huntingdon at this time 16 churches, two priories, a friary and three hospitals.

It was during this period that the process of early nucleation, which started in the middle Saxon period, came into full swing in the two counties. In the early medieval period, the village was not a 'settlement with a compact group of houses' as intended today, but either a 'nucleation of inhabitants in a single centre or a scatter of hamlets and farmsteads' (Dyer 1994, 408; Roberts and Wrathmell 2022). This was part of a wider expansion process that included a re-organisation of the landscape as much as the villages and hamlets. Non-nucleated villages were set in a more open landscape - such as woodland and pasture (Dyer 1994, 410) - and less rigidly controlled for the management of resources. Now, with more of a focused nucleation of the settlements came the expansion, re-organisation, and reclamation of more marginal areas and the use of different agricultural strategies to improve productivity, such as the introduction of manure (Jones 2012) and more intense management of animals (from free-grazing to enclosures) or perhaps more highly regulated use of common pastures.

Despite the lack of archaeological evidence, it is possible to assume that during this period, the largely un-nucleated hamlets and villages surrounding the A14 scheme became nucleated. The documentary and archaeological evidence are supported by the survival of medieval churches within the existing villages of Boxworth (CHER 00247), Lolworth (CHER 01283), Offord Cluny (CHER 02458) and Fen Drayton (CHER 14837) and by remains of medieval settlements identified during archaeological investigations within the core of modern villages and towns in this area (Fig. 6.2). Examples of these are the medieval pits, ditches, post-holes, ovens and gullies identified at Buckden (CHER 20274), Offord Cluny (CHER 15038) and Fen Drayton (CHER 20414).

Documentary evidence and earthwork remains attest also to the evidence of at least five deserted 'shrunken' villages in this area: Boxworth (CHER 03528, 19346, 23144, 25512), Conington (CHER 25780, 25782, 25784), Fenstanton (CHER 25793, 25794), Lolworth (CHER 03500, 23129, 25514), and Houghton (CHER 11422). All of these, except for Brampton, comprise earthwork remains that have not been excavated. There were no earthwork remains for the deserted medieval village of Houghton (CHER 11422), and prior to the A14 excavations, this was only recorded on historic maps and documentary evidence (see below).

According to documentary evidence and earthwork remains, the area was also characterised by the existence of five moated manorial complexes at Boxworth (CHER 01088, 01089), Alconbury (CHER 00793), Fenstanton (CHER 01083, 11972), Lolworth (CHER 01090), Bar Hill (CHER 06127) as well as a medieval double-moated enclosure at Ellington (CHER 00773). Archaeological excavation at Fenstanton (Grove House) revealed two 10th to 11th-century pits within the moated enclosure, evidence for the infilling of the moat, and a 15th to 16th-century ploughsoil sealing the area (CHER 11972).

The use of the land throughout the medieval period was characterised by a mixture of arable and pastoral practices with, depending on the environment, more specialised activities such as wood pasture or pastoralism. In the area associated with the A14 mitigation, agriculture seemed to be the primary land use that was represented by field subdivisions, both as enclosures or field systems visible as earthworks, archaeological features, or referred to in documentary sources; trackways, drainage ditches and ridge and furrow. There was also evidence, albeit limited, of gravel or clay extractive activities on different landscape blocks, of the manufacturing industry such as blacksmithing, textile production and (possibly) brewing at Houghton, and pottery production at Mill Common in Huntingdon.

The Great Famine of 1315-1317/22 brought about by the beginning of the Little Ice Age, followed by the Black Death pandemic that took hold of Europe between 1346 and 1353 (Dyer 2010) slowed down these activities considerably. The succession of these two calamities caused a contraction in the economy and population growth that can also be seen in the archaeological record.

Documentary evidence dating to the 14th and 15th centuries suggests that during the 14th century, Huntingdon's decline began, starting with the demise of St Ives fair weakening the local economy, followed by a decrease of the population and the poor state of the local economy. By the mid-14th century, it seems only ten of the sixteen churches were still in use. By the 16th century, only St Mary's, All Saints, St Benedict's and St John's churches were still functioning (Clarke 2006, 6).

Documentary evidence of the same period suggests the same fate for Cambridge with evidence of economic stagnation starting in the mid-to-late 14th century, which was followed by the abandonment of dwellings and closure of churches such as the Church of St John Zachary and the Church of All Saints by the Castle after the Black Death. In 1446 a petition filed by the burgesses lamented a further loss of population and trade. This was attributed to the encroachment of colleges on businesses, but it was exacerbated by the state of the economy across the country at the time (Roach 1959, 110).

Much of the A14 area remained agricultural throughout the post-medieval and modern periods. The evolution of farming practices and the process of Enclosure saw a change in the field systems with a forced move from the communal open fields to a more divided landscape, which is reflected both in the landscape today and in the archaeological record. Although finalised in the 18th century with parliamentary enclosure, this process was started in c. 1500 and was affirmed by the 17th century (Wordie 1983). From the very first parliamentary Enclosure Act in 1604, specifically applied to Radipole in Dorset, to the last 20th-century award, a total of 6,436,188 acres were enclosed in England and Wales. Although the 1760 enclosure act was the one historically considered the most important, it was estimated that between 1604 and 1760, at least 228 Enclosure Acts were passed (Wordie 1983, 486), enclosing approximately 358,241 acres of land. By 1607, approximately 5.25% of the land in Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire was enclosed (Gay 1903; Johnson 1963; Wordie 1983, 491). The conversion of agricultural open land into sheep management enclosures hit Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire less than other counties. In Warwickshire between 1450 and 1485, for example, 72 settlements were abandoned, owing to the conversion of agricultural land to sheep pastoralism (Beresford 1951, 133). The enclosure of open land for more focused farming at the end of the 16th century also occurred in Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire but, as previously, less so than in other counties (Beresford 1951, 144).

Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire were not major battlegrounds during the Civil War but felt the consequences heavily. The war brought considerable disruption to the economy. Armies marching through the counties often requisitioned supplies, leading to scarcity and inflation and many areas were devastated by the constant movement of the armies, looting and destruction of properties. Agricultural activities as well as trade were severely affected, leading to food shortages and economic hardships for the local population.

Cambridgeshire contributed soldiers to both the Royalist and Parliamentarian armies with the conscription of local men, many of whom never returned home. This loss of manpower had long-term consequences for the county's workforce and communities. Cambridge was a site of strategic importance during the war and in 1643 was besieged by Parliamentarian forces who sought to control the university town, castle, and its defences (Roach 1959, 15-29).

Huntingdon, Oliver Cromwell's hometown, like Cambridge, was of strategic importance owing to its position and was involved in a brief but significant siege in 1645 (Hutton 2021, 8-13). The Royalist garrison held the town but ultimately surrendered to the Parliamentarians and the skirmishes between the two sides brought damage to the town's defences and buildings. The Civil War created divisions among the people of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire, with some supporting the Royalist cause and others siding with Parliament (Hutton 2021, 79). After the Parliamentarian victory, local governance structures were reorganised, and individuals who supported the Royalists faced penalties and confiscation of properties, damaging the economy further.

After the war, the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 marked the end of the Commonwealth period and brought relative stability to the region. The effects of the war, however, lingered and it took time for both counties to recover economically and socially.

It was from the end of the 17th century that the economy started to recover in both regions. Agriculture remained the dominant economic activity supported by a thriving wool trade, moderate textile manufacturing and milling. The River Great Ouse facilitated river transportation, contributing to Huntingdon's economy. The major market towns of Cambridge, Ely and Wisbech, a port town, played a crucial role in facilitating trade in the region as well. The continued efforts to drain and reclaim the Fenlands of Cambridgeshire made previously marshy lands suitable for agriculture, further boosting the region's agricultural output (Hutton 2021, 8 and 9). It is during this period that larger houses, gardens, and parks were created within some of the settlements across the area, namely Alconbury Park, Brampton Park, Buckden Little Park, Conington Hall and Park, Boxworth House, Lolworth Grange and Girton College.

The late 18th and 19th centuries saw the advent of the Industrial Revolution and, although the two counties were not major industrial centres, the region saw an expansion in textile, milling and engineering activities. The region was characterised by infrastructure improvements as well, such as the expansion of railways and roads, connecting the counties to the national transportation network (Balchin and Filby 2001; Moretti 2022). As seen below, the Great North Road played an important role in the history of Houghton.

During the 20th century, both counties played a significant role during World Wars I and II hosting military bases, airfields, and training facilities such as at Mill Common in Huntingdon (Moretti et al. 2023) contributing to the war effort. Some evidence for features associated with the two World Wars is recorded in this area, including pillboxes in Brampton Hut (CHER 15210), Fen Drayton (CHER 15203), Girton (CHER 10397) and a Royal Observer Corps Post in Buckden (CHER 16436). RAF Brampton was a base from the First World War until relatively recently.

Archaeological evidence for other, more general, post-medieval activity has been identified in the area, including brickworks at Boxworth (CHER 25510); earlier farm buildings at Whitwell Farm in Offord Cluny (CHER 24112); and gravel pits in Conington (CHER 25788), Offord Cluny (CHER 15038), Girton (CHER 18274, 19899), and Fen Drayton (CHER 20969, 25812).

Evidence of medieval agriculture activities was present across all eight landscape blocks of the A14 mitigation. These were mainly remains of field systems, boundary ditches, fence post-holes, wells, and ponds (see Table 6.1).

Seven landscape blocks - Alconbury, Brampton South, Brampton West, Fenstanton Gravels, West of Ouse, River Great Ouse and Conington - presented different alignments of medieval plough furrows suggesting different periods of farming or subdivision of the areas by separate fields or furlongs. At West of Ouse (TEA 16) the medieval ridge-and-furrow earthworks did not extend over the barrow, as it was - then and at the time of excavation - still visible as a slight upstanding earthwork. The barrow itself seemed to delimit the extent of the medieval cultivation as no furrows were identified in the area to the east, towards the river. Brampton West provided the most extensive medieval evidence with the remains of part of the hamlet of Houghton (Fig. 6.3).

Settlement Brampton West 5 (BW5), historically known as the village or hamlet of Houghton, was established before the Norman Conquest and appears from the archaeological records to have been partially abandoned by the end of the 13th century, with a smaller scale return to the settlement in the mid-14th to early 15th centuries before the settlement was entirely abandoned. This diverges from the historical records, which indicate instead a continuous occupation throughout the 13h and 14th centuries.

The archaeological remains of Houghton were uncovered around the northern, western, and southern edges of TEA 7C, surrounding an open area within the centre of the excavation area where settlement BW3 (Chapter 5) had been located. The total exposed area was approximately 10ha (Fig. 6.4). The settlement did not continue east but is likely to have extended to the north of the A14 scheme area (CHER 11422). An earthwork visible on Google Earth imagery as a line of trees aligned NNW-SSE before turning north-east to the north of TEA 7C may represent the north-western corner of the settlement (Fig. 6.5). Further evidence of the edge of the settlement is represented by the south-western copse of trees between TEAs 7A and 7C.

Houghton probably developed as an outlier (or daughter settlement) to the main medieval settlement of Brampton, as it had no church or manor house. This identified its character as a 'hamlet' (rather than a village), which developed on the western edge of the territory of Brampton, c. 250m to the east and north-east of Brampton and Harthay Woods and 200m to the west of the Great North Road (West et al. 2024, 207) (Fig. 6.5). The proximity of Houghton to both Brampton and Harthay Woods, as well as the Great North Road, likely influenced the development of this hamlet. A blacksmith's workshop identified within the settlement might have catered for the travellers along the Great North Road and the people coppicing and pollarding the nearby wood. Its position on the higher ground may have facilitated its visibility and access from the road. The area surrounding Houghton was utilised for arable agriculture and was represented by Field System 4 to the east and the furrows recorded across the rest of the landscape block (Field System 102).

Professor Christopher Dyer provided the documentary evidence on Houghton discussed in the following paragraphs (see also West et al. 2024).

The place-name, Houghton, assumed to be of pre-conquest origin, indicates a settlement by a hill spur. The conjectured date for its adoption is possibly the 8th century (Gelling 1984, 167-9) and perhaps refers to the Saxon settlement BW3. The place-name persisted and was maintained throughout the settlement changes, but it appears to have been changed to Woodhoughton by the 13th century, as officials needed to distinguish between Houghton in Brampton and the larger village of Houghton near St Ives, clearly marking its connection to the nearby Brampton Wood. Houghton's location within a road network already established in the 11th century might have been beneficial for its economy.

The earliest documentary evidence of Houghton as a separate settlement from Brampton is dated to 1279 when juries reported to a royal survey about tenants and their holdings in each village, the first enquiry of this kind since Domesday. Only fragments of the resulting Hundred Rolls survive, but they include a complete coverage of Huntingdonshire. The list of tenants at Houghton was a subdivision of the survey of Brampton but clearly distinguished from the main village. There were 34 tenants, of whom 20 held messuages (houses and associated buildings) and were likely to have been inhabitants. Their lands amounted to 240 acres of arable and 37 acres of meadow. No details are given of pasture, as this would have been a share of grazing on commons, which could not be expressed as an acreage (Illingworth 1812-18, 607-10).

The archaeological evidence appears to indicate that Houghton reached its peak in the mid-13th century followed by a steady decline, reaching a low level of activity in the early 14th century. The archaeological evidence also showed a small-scale revival at the end of the 14th century and into the early 15th century, which was then followed by total abandonment.

The documentary evidence, however, seems to depict a well-populated settlement in 1279, with no hint of decline. Furthermore, the Houghton tax-payers list of 1327 indicated a total of 46 tax-payers. Nine of these had surnames found in the survey of Houghton made half a century earlier (Raftis and Hogan 1976, 213-14), indicating continuity in the family ties of Houghton. This continuity appears also in the court roll of 1350, which not only mentioned one of the 1338 rebels from Houghton but also lists at least seven people from Houghton taking part in the 1338 rebellion and, as in the tax list of 1327, some of the surnames were also found in the hamlet in 1279 (Hunts Archives, Box 4/3A). Dyer (in West et al. 2024) suggests that if seven names were listed among the rebels, an equal or larger number of names did not take part in the rebellion. This would push the numbers to 14 to 20 heads of households at Houghton in 1338, at the time when archaeologically the settlement appears 'abandoned'. This would constitute a rather large hamlet considering that the typical size was between 5 and 10 households, with 30 households in Wharram Percy at its peak in the 14th century (Beresford and Hurst 1990). Although it is difficult to establish the average size of a medieval family in England, a 3.5 average size per family has been postulated here (Krause 1957). This would give a presumed total of 49 to 70 people residing in Houghton in 1338.

So why are there these discrepancies between the documentary sources, suggesting a survival of the settlement throughout the 13th and 14th centuries, and the Bayesian modelling and the archaeological evidence (finds and features) suggesting a decline of the settlement at that time, until its eventual abandonment in the mid-15th century? Why does Houghton have two different stories? One possible reason for the discrepancies is that the archaeological investigation only identified part of the original hamlet and that further remains of structures and tofts, possibly later in date, exist beyond the excavation limits.

It is possible that after the famine, climatic downturn, and subsequent diminishing resources from 1315, the inhabitants of Houghton felt the restraints and adopted a stricter domestic economy. This would have been characterised by less wastage not only in food and drink but also on household items such as pottery or metal objects (the archaeological evidence of this would be the survival of older pottery typologies and limited metal finds), and with a more 'spartan' approach to building maintenance. The pottery assemblage from Houghton, typical for a rural settlement, included pottery typologies such as unglazed St Neots, with smaller quantities of glazed Stamford ware and Lyveden-Stanion ware, characterised by a long 'lifespan' and as such supporting the possibility of longer but less visible activity at Houghton.

It is possible, therefore, that where these elements have been interpreted as a slow abandonment of the hamlet, they perhaps indicate economic contraction or deterioration that does not imply abandonment.

They could also indicate settlement drift, where the village drifted outside the excavation area. Equally it could mean a change in construction techniques from earth-fast construction to ground-set timbers (see Houghton's structures). If the later structures did not break ground they may be entirely invisible archaeologically. It is possible that despite the fact that the inhabitants of the excavated part of Houghton became more invisible in the archaeological record, they were still there throughout the 13th and 14th centuries.

Moreover, it is conceivable that the economy of Houghton relied more heavily on Harthay and Brampton Woods than previously assumed. The comparative analysis of the remains of houses, when juxtaposed with similar sites such as West Cotton in Northamptonshire or Wharram Percy in Yorkshire, reveals more indications of poverty and economic deterioration at Houghton. This observation is further supported by the limited range and quality of artefacts and the predominantly domestic nature of the pottery discovered. Two possible explanations for these circumstances are an economy predicated on either the volatile demand for woodland products or the enforcement of increasingly stringent Forest Laws. The latter would result in the loss of communal rights to the woodland or the deforestation of sections within Harthay and Brampton Woods, subsequently leading to their clearance for agricultural purposes (assarting).

The transition between the Saxon and Norman periods has been, historically, a challenging subject ranging from the idea of a 'cataclysmic event' characterised by a total reshaping of the English landscape and culture by 'Norman import' such as castles, cathedrals, and monastic churches, to the more recent idea of a 'nuanced albeit still perceptible change within an already vibrant and diverse cultural background characterised by European, Scandinavian and pan-regional influences already in place before 1066' (Liddiard 2017, 105-6).

In order to assess the possible changes brought on by the Norman Conquest in England, these changes have to be separated from those brought on by wider shifts in society not associated with the Norman Conquest. These changes, such as the population growth which saw a peak in the mid-to-late 12th century across Europe, in turn brought on further changes. These were represented by the expansion of arable and assarting land, bringing woodland and wood pasture under threat and the privatisation of these for the benefit of the barons and lords, with the push of emparking as seen across Europe in the two centuries after AD 1000 (Liddiard 2017, 116). Furthermore, these changes can also be seen in the more frequent construction of high-status structures, the development of Forest law (Liddiard 2017, 116), and settlement planning.

Historically speaking, closely dating archaeological evidence from villages, hamlets, and farms immediately before and after the Norman Conquest has been difficult. This has rendered the original categorisation of 'nucleated' village pattern versus the 'dispersed' hamlet and farm patterns a highly debated topic. Despite this debate, both documentary and archaeological records show the clear development of 'nucleated' villages by 1200 - at least in the 'midland shires' (Liddiard 2017, 120). The concept, however, that the development of a nucleated and regular village was the result of a precise event either by the lords or the communities to restructure the planning of the village is now considered obsolete. The expansion of archaeological knowledge is increasingly supporting the idea that the nucleated village happened as 'a consequence of the reorganisation of the settlement's attendant field system and the expansion of house plots over nearby land' (Williamson et al. 2013, 81-7). This has been observed in some cases in Northamptonshire where the re-examining of the idea of 'nucleation of a formerly dispersed pattern of settlement during the middle or late Saxon period … resulted to be more a myth than a reality' (Williamson et al. 2013, 81 and 87).

Further, the idea that 'the Normans were so good at assimilating that they assimilated themselves out of existence' (Fernie 2000, 303) might explain to a certain extent the paucity of archaeological evidence regarding the possible changes brought by the Norman Conquest in the development of pre-conquest settlements and hamlets. Specifically, the concept that these changes did not actually take place but rather that there was a development of the original settlement and settlement location over centuries, as seen at Brampton West. Here, from an open scattered settlement characterised by SFBs and some post-built structures - some of them as early as the 5th century - and a middle-Saxon settlement (BW3) characterised mainly by post-built structures arranged in a semi-organised layout, the settlement landscape developed further in the late Saxon and medieval period. Approximately 180m to the south-east of BW3, a separate late Saxon enclosed settlement (BW4) and associated field system developed between the 10th and 12th centuries, whereas the larger and longer-lived medieval settlement (BW5) was located immediately to the west of BW3, with buildings organised along a road (see Chapter 5 for details of Saxon settlements). This developed into the medieval settlement of Houghton, indicating perhaps the movement of the population from the settlement (BW3) across into BW5/Houghton.

The period of transition between the Saxon and the Norman periods at Brampton West was represented by settlement BW4 in the south-eastern corner of TEA 7BC, as seen in the previous chapter. Dating evidence from the pottery and radiocarbon samples indicates that BW4 was abandoned in the 12th century, with little evidence for any continuity into the 13th century or beyond, apart from two boundary ditches (Ditches 7BC.111 and 7BC.59). Ditch 7BC.59 may have continued as a north-east to south-west aligned ditch shown on the 1772 Inclosure Plan (see Fig. 6.19). According to Stuart Wrathmell (pers. comm), the short-lived character of settlement BW4 could be an indication that this was a short-lived demesne farm created by the King's administrators at Brampton.

Evidence for this transition period can also be seen in the layout of BW5 and Field System 4, which appeared to respect (as an open area or village green) the area where BW3 was originally located (Fig. 6.4). This 'village green' may represent an area kept as permanent pasture, as seen in other medieval villages in eastern England and East Anglia, or it could indicate an area used as a cultivated open field, as seen for example at Whittlesford (Cambridgeshire) and Stanfield (Norfolk) (Roberts and Wrathmell 2002, 109). Many greens in the southern part of Cambridgeshire are thought to date to the early or middle Saxon period (Taylor 2002; Oosthuizen 1993; 2006, 51-9); however, in this case, the 'green' element is clearly later.

In addition to this, the archaeological evidence and the Bayesian modelling (see Table 5.2 in Chapter 5) indicate a potential crossover between settlements BW3 and BW5/Houghton. Specifically, two post-built structures and pits identified in BW3 (see Chapter 5) presented a late Saxon date, whereas some structures identified in BW5/Houghton (see below) returned a pre-conquest date, indicating the co-existence of the two settlements in the 10th century.

The initial phase of the settlement, dating to the late 10th and 11th centuries, was identified in the northern and western areas of TEA 7C (Fig. 6.6). This phase comprised various components, including the earlier phase of a north-east to south-west aligned northern street (Trackway 1), eleven structures, three pit groups (some displaying signs of burning), quarrying operations, a kiln, and an oven. Radiocarbon dating results suggest that certain elements of this phase pre-date the Norman Conquest, with no temporal gap between the latest stage of BW3 (cal AD 990-1150) and Houghton's earliest phase (cal AD 880-1000 - BW 3 (Structure 7BC.265, SUERC-91421); Settlement 5 (Structure 7BC.509, SUERC-91422).

The northern street (Trackway 1), of which approximately 80m in length was identified, constituted the principal feature in the northern section of the settlement. Pottery findings from the ditches defining this street consistently yielded dates from the 11th century.

Four of the structures identified and associated with this phase were situated to the south of the street, three to the north and five to the west. The four structures positioned south of the street were intentionally arranged parallel to and along its southern edge. It is plausible that some of these structures continued to be used in Phase 2. The dating evidence primarily pointed to the 11th-century period, with a few pottery fragments from the mid-13th century.

Structure 7BC.529, located to the north of Trackway 1 (Fig. 6.7), represented the most distinct among the three buildings in that vicinity. This rectangular building featured external post-holes, larger posts on its north-western side, internal divisions delineated by rows of posts, and scattered internal post-holes. The pottery assemblage recovered from this structure predominantly dated to the mid-11th century. Radiocarbon dating indicated that it was constructed during the pre-Conquest era, potentially slightly later than Structures 7BC.506 and 7BC.509. As well as food production, this structure yielded a considerable quantity of cereal grains as well as flax seeds (González Carretero 2024). These might suggest a possible involvement in linen production. Some of the pits to the south-east of the structure (Pit Group 7BC.531), arranged in pairs on a line 10m long, contained frequent charcoal, fired clay, and abundant plant remains. This suggests that they may have functioned as simple corndryers, perhaps later used as refuse pits. Alternative uses of the pits might include fire-pits, or housing circular wooden tubs for processing products.

The two structures to the west (7BC.470 and 7BC.490) lacked any discernible arrangement and their size and layout remain unclear. The pottery findings from these structures dated to the mid-11th century. Radiocarbon dating corroborated the classification of these structures as part of Phase 1. The purpose of these structures remains unknown, although some may have served as dwellings, while others might have functioned as barns and agricultural buildings or workshops associated with quarrying activities. There is no evidence of a field system or land division linked to this early phase.

The subsequent phase of the settlement, in the 12th and 13th centuries, witnessed the formalisation of the hamlet's layout (Fig. 6.8). This phase involved the establishment of primary streets (Trackways 2 and 3) and a secondary street (Trackway 4), as well as boundaries demarcating the settlement from the central open field (Linear Boundaries 5 and 6) and various plot boundaries. Excavated features within the settlement comprised buildings, pits, wells, ovens and industrial pits. This phase represents the most intensive period of activity within the settlement.

The settlement was delineated by its streets (north, west and south) with the north one (Trackway 2) serving as the primary route through the northern and western areas, the south street (Trackway 3) traversing the southern part, and the west street (Trackway 4) branching off from the north street, possibly leading towards Brampton Wood (Table 6.2). These streets were developed in the 12th century and played a central role in organising settlement activities. The north and south streets remained in use during the later medieval periods and even into the post-medieval era, likely serving as agricultural routes.

| Trackway/Street | Dimensions | Direction (L x W) | Composition | Dating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 440m x 5m to 16m | NE-SW and S | Holloway form in the north and south | 12th to 13th century (with some 11th and 14th century pottery) |

| Raised metalled surface in the west | ||||

| 3 | 250m x ? | NE-SW | Parallel Intercutting ditches | 12th century |

| 4 | 21m x 10m | NE-SW | Parallel ditches and partial metalling |

Evidence from the 1772 Inclosure Map (see Fig. 6.19) and the curvature of ditches in the north-east indicates that the north street (Trackway 2) likely curved northward, potentially preceding the enduring north-south track. The north street (Trackway 2) intersected the south street (Trackway 3) in the southern part of the settlement. In this map, the north street appears to continue as a lane around what became known as Rev. Taylor's Glebe Land and out further west towards Brampton West. This is a parcel of land, which, corresponding to the location of the HER points for the abandoned medieval village of Houghton, might be where further remains of Houghton could be located. Further, on the east side of this land parcel, the north road appears to have a junction with a track towards what became, in 1663, the Great North Road.

Although the physical connection between the north and south streets was not observed, both streets were established concurrently and served as prominent features and potential boundaries within the Houghton settlement. The south street (Trackway 3) likely extended south-west beyond its junction with the north street (Trackway 2), forming a 'T-junction' and linking Houghton to Brampton Wood. The west street (Trackway 4), located in the western part of the settlement and aligned approximately east to west, may have continued south-west towards Brampton Wood. Its absence from later historic maps suggests that the west street ceased to be used by that time.

The settlement's boundaries were defined by two primary ditched features (Table 6.3). Linear Boundary 6 acted as the north-eastern boundary, separating Houghton from the central area previously occupied by settlement BW3. Linear Boundary 5 served as the hamlet's southern boundary. These boundaries were established during the formalisation of Phase 2 in Houghton, reflecting efforts to demarcate and organise the settlement. The existence of other boundaries beyond the excavated area remains uncertain, although the 1772 Inclosure Map (see Fig. 6.19) implies that the south street (Trackway 3) may have also functioned as the effective southern boundary of the settlement.

| Linear Boundary | Dimensions L x W x D | Direction | Composition | Dating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 270m x 2/2.5m x 0.5/1.1m | NE-SW and W | Ditch 7BC.345 | 12th and 13th centuries |

| Ditch 7BC.346 | ||||

| 6 | 275m x 0.35/0.85m x 0.05/0.2m | NE-SW | Ditch7BC.541 | |

| Ditch 7BC.542 | ||||

| Ditch 7BC.543 | ||||

| Ditch 7BC.544 | ||||

| Ditch 7BC.545 |

The 1772 Inclosure Map shows that Linear Boundary 5 persisted as a delineation for an agricultural plot of land into the post-medieval era. However, it had been removed by the time of the 1808 Ordnance Surveyors drawings and was later truncated by the 19th-century Brick Kiln 7BC.344. Linear Boundary 6 ended just before the north street (Trackway 2) in the west, possibly serving as an entrance into the hamlet. It was not observed to the east beyond the modern trackway. Three gaps were found between its ditches, likely serving as access points between the settlement and the fields. Some sections of the boundary had post-holes, suggesting the presence of a fence, while others were irregular, possibly indicating a hedge-line. The purpose of this boundary was probably to separate the settlement from the surrounding fields.

In the northern and western parts of Houghton, activity was concentrated north and west of the north street. Its northern side exhibited a more organised layout, featuring north-west to south-east aligned plot boundaries dividing the area into smaller plots. Structures and pit groups were found in this area. On the other hand, the southern side had fewer structures and no evidence of plot divisions, with the smithy and associated pits present. It is possible that the southern area was used for 'industry' while the domestic occupation was focused on the northern side. The western part of the area consisted mainly of pit clusters, indicating extraction or industrial activity, and included one significant L-shaped boundary and one structure. Some of the pits contained dark burnt clay-silt fills with frequent charcoal inclusions representing the dumping of burnt material. The environmental evidence indicates the presence of mainly wild seeds from arable grasses (suggesting that the burnt material did not derive directly from woodland crafts such as ash burning or soap boiling).

In the southern part of Houghton, the main activity was associated with the south street (Trackway 3) and Linear Boundary 5. Unlike the northern and western parts, there was no evidence of occupation beyond the 13th century. Here, only domestic activity was identified, with plot divisions following different orientations as well as several structures. This part of the hamlet had four post-built structures and one structure characterised by beam-slots. The structures were sub-rectangular in shape and varied in size between 10m by 8.5m and 18m by 8.5m. Additionally, there was a well and two pit clusters serving this area.

The activity in the northern and western parts of Houghton during the 12th and 13th centuries was a continuation of the earlier phase, particularly along the western side, whereas in the south the activity appears to belong only to Phase 2. The character of activity was similar, but more formalised, especially along the northern side, with the construction of the north street (Trackway 2), Linear Boundary 6, and plot divisions.

A total of eight buildings from the 12th and 13th centuries were identified in the northern and western parts of Houghton, primarily located to the north and west of Trackway 2. Building 7BC.546 was the only one with a clearly identifiable ground plan. These buildings included groups of post-holes, beam-slots and a combination of both.

Structure 7BC.513, to the north of the north street (Trackway 2), was different in construction from the other buildings in Houghton (Fig. 6.9). It comprised an area of stone bedding measuring 5.2m by 1.4m by 0.18m deep, with a stone-filled post-pad 0.7m to the north-west, and three other post-holes around the stone area. Pottery dating was mixed but included 76 sherds of late Saxon, 11th century, and mid-13th century date - representing the highest concentration of pottery recovered from any of the structures in the settlement. This was all covered by Deposit 7BC.514, which may have been a preparation area for a later building (see discussion below). This structure was also the only building within the settlement of Houghton with significant quantities of animal bone (Faine 2024b). This, combined with the different character of the structure, suggests that it may have had another function from others in the settlement, potentially for the processing of animal remains. Maybe, situated so close to the north street (Trackway 2), this represented not only a butcher's shop servicing the settlement but also providing services for the travellers along the Great North Road and the east-to-west road.

Structure 7BC.546 was a clearly defined smithy located south of the north street (Figs 6.10-6.12). It had a sub-rectangular shape, measuring 8.7m long by 3.8m wide, with a truncated northern side owing to a post-medieval land drain. The structure consisted of 16 outer post-holes, a beam-slot along the south-eastern edge, and four post-holes potentially forming a covered entrance or small annexe. Replacement of external post-holes indicated maintenance. Inside the structure, three post-holes divided it into two areas, and a sub-circular shallow pit in the centre could represent the remnants of a hearth, surrounded by five stake-holes possibly used to support bellows. Examples from the same period indicate that the hearth was most likely a waist-height structure.

Pit Cluster 7BC.337, located south-west of the smithy, was a cluster of sub-rectangular pits covering a 4.4m by 1.5m area. These pits, approximately 0.7m deep, contained three fills, including lower silty-clay formed through natural infilling and two dark silty-clay fills with charcoal, fired clay, and slag as deliberate backfills. These pits likely served also as waste disposal for metalworking.

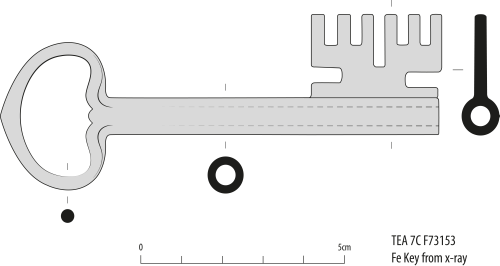

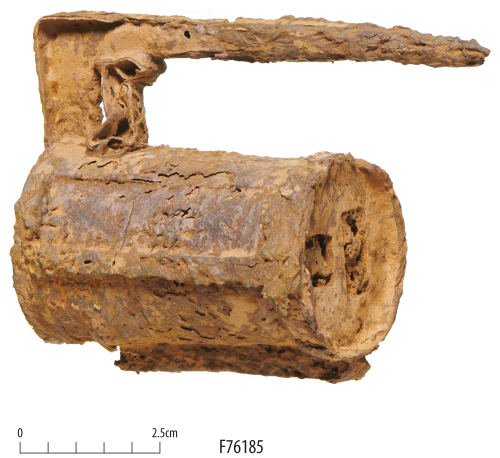

The smithy yielded significant amounts of iron-working slag, including 1444g from the central hearth and 1044g from an external post-hole. Smithing hearth bottoms, hammerscale, and possible bloom fragments were among these remains, suggesting smithing and smelting activity. Other finds included a small quantity of pottery, animal bone, and ceramic building material. Oak charcoal from one of the post-holes was radiocarbon dated to cal AD 660-780, but it was attributed to the 'old wood' effect rather than the structure being of Saxon origin. Metal items such as horseshoes, horseshoe nails, locks, and keys, indicative of medieval smithing activity, were found across the site.

The archaeological remains of the smithy provide insights into its subdivision and spatial functionality. Its location, in the north-eastern edge of the hamlet but near the main street, is typical of the time owing to the danger of pollution and fire yet easy accessibility from the main access road (Franklin 2020, 142). It is possible that the entrance was on the north-western side or north-eastern end facing the north street (Trackway 2). Post-holes of sub-group 6, traditionally interpreted as a small annexe, could represent a covered or enclosed pre-working area facing the north street, perhaps designed to facilitate work on horses and carts. Inside the smithy, two distinct areas demarcated by post-holes of sub-group 4 likely constituted the main working area, with the forge located near the centre. The post-hole of sub-group 5, presenting stone padding, may have held the anvil block as did the one identified at the South Witham smithy (Mayes 2002, 37). Its position, close to the south-western wall, follows the spatial arrangement of later smithies (Light 1984; 1987; 2007; Fleming 1986; Killick and Fenn 2012).

These smithies had the anvil a few steps away from the forge, near windows or openings for better visibility and light during the shaping and hammering of heated metal.

The separate northern section of the smithy may have served as a domestic space for the smiths and their families, or a shop front for customers or storage for iron stock. The beam-slot along the south-eastern edge initially thought to be a wind-screen, could also be the remains of a lean-to shed used for storing fuel outside the smithy, to mitigate the fire risk of storing it within the forge itself.

By the late 13th century, most of the excavated area of Houghton appeared to be abandoned - from an archaeological point of view. A small area in the northern part, however, showed signs of activity in the mid-14th century. This area, approximately 0.40ha in size, revealed possible structures, pit groups, and a large ditch.

Although no definite 14th-century structures were identified, Deposit 7BC.514 and Pit 730381 suggest the presence of sparse remains. Deposit 7BC.514, a grey-brown silty-clay deposit, sealed the earlier Structure 7BC.513, covering an area of 12m by 11m. It contained pottery from the late 12th, mid-13th, and late 14th centuries, implying a shift in usage. Pit 730381, a sub-rectangular pit with a flat base, had post-holes and late 14th-century pottery, indicating a possible structural function.

On the southern side of the north street, there were pit groups and a ditch also dating from the 14th century. The only 14th-century feature in the southern part of the settlement was Well 7BC.347, which contained late 14th-century pottery. This well disrupted the previous settlement layout, suggesting it was established after the abandonment of that area, potentially for agricultural purposes.

In the north-western corner of the settlement (Fig. 6.13), a small area of later medieval activity was discovered, dating to the 15th century. Positioned near the hill's brow where the north street curved south, this consisted of a structure, two bounding ditches, and four adjacent pits as well as Structure 7BC.485. The pottery recovered from these features (Fig. 6.14) indicated a late 14th to late 15th-century date, suggesting a direct continuation of Phase 3 activity. The nature of these remains was predominantly domestic, with evidence suggesting a small-scale short-lived occupation.

A total of 28 possible buildings were identified within the medieval settlement - twelve assigned to the 10th-11th-century phase, thirteen to the 12th-13th-century phase, two to the 14th-century phase, and one to the 15th-century phase. This settlement provided an invaluable opportunity to study medieval buildings, particularly from the earlier centuries (10th-13th centuries).

Twenty-one households were recorded in the 1279 Hundred Rolls, but as only thirteen buildings were identified in the 12th-13th-century phase it is likely that others are archaeologically invisible. It is also possible that some of the buildings were located outside the excavated core of the hamlet and beyond the scheme boundary.

The buildings mainly comprised groups of post-holes and beam-slots, typically rectangular in shape and measuring between 6m by 2m and 15m × 2m. During the earlier phase these structures seemed to maintain a north-east to south-west alignment, whereas in the later phases the orientations were more diverse. This appears to have been the norm for the structures in Phase 1 and 2 of the settlement, with the exception of Structure 7BC.513 which comprised an area of stone bedding surrounded by post-holes and a stone-filled post-pad. It is thought that across the country there was a shift from earth-fast construction (posts in holes or trenches) to ground-set timbers (placing timbers on the ground) between 1150 and 1250 (Gardiner 2014). As the latter would leave little or no archaeological trace, it could not be definitively identified in Phase 1 and 2 of this site. However it might explain the apparent relative lack of medieval structures found in relation to the historically recorded number of messuages. It might also explain the more extreme lack of later medieval structures at the site.

Differences in construction methods were clear in the 14th and 15th-century phases. A wider variety of building types (and materials) was represented by the later structures (14th and 15th century), with Deposit 7BC.514 potentially functioning as a consolidation layer for a building. Pit 730381 possibly had a structural function in a similar way to SFBs. Structure 7BC.485 comprised a stone surface, a stone-filled beam-slot and three post-holes. Some of these structures could be assigned definitive functions, whereas some of the early structures in the western part of the site may have been associated with quarrying. Other structures were more likely domestic dwellings, primarily based on the quantities of pottery recovered from them, most particularly Structures 7BC.474 and 7BC.350 and the 15th-century Structure 7BC.485 (with adjacent associated rubbish pits).

It is difficult to establish the 'lifespan' of these structures. The argument proposed by Wrathmell that the lack of evidence indicative of the maintenance of existing buildings does not necessarily mean that maintenance, or attempts 'to extend the life of the buildings', did not take place and this should be considered in the case of Houghton (Wrathmell 2001, 184). Here, as everywhere in the country, the depletion of the timber reserve caused by either emparkment or assarting would have represented a major impact on the construction of new buildings or the way they were maintained with perhaps the development of more 'complex jointing to hold them together'. This type of maintenance or any other type of maintenance or patching affecting the timber structure above ground would have left no archaeological evidence, consequently limiting the use of archaeological evidence to estimate the life span of a building.

The fact that there is limited evidence for the maintenance or replacement of these structures might suggest that they likely lasted for as long as the 'settlement' did, with those established in the 12th-13th-century phase (alongside the formalisation of the settlement) lasting until the settlement was possibly abandoned at the end of the 13th century - a period of perhaps 100-150 years. Archaeological evidence from the medieval hamlet of West Cotton, Raunds, in Northamptonshire (Chapman 2010, 160-62) would suggest a similar 100-year lifespan. This was also observed at Wharram Percy where, when maintained, medieval buildings were built to last for centuries (Wrathmell 1988).

Evidence for structural materials was limited, with daub the most commonly encountered material, suggesting most buildings were timber-framed with wattle and daub wall panels. A small assemblage of ceramic building material (two peg tiles, one ridge tile, one fragment of a roof tile, and one possible roof slab) suggests that some of the buildings may have been partially tiled at the ridge and gable ends with otherwise thatched or shingle roofs. The paucity of structural materials at Houghton is common across England where, even in areas characterised by an abundance of stone for construction, peasant houses were still built in wood up to the 12th century and in some cases (such as Wharram Percy), up to the 13th century, then becoming less ubiquitous for the construction of foundations (Hurst and Moreno 1973, 813).

At Houghton, the ceramic building material was solely found in features in the southern part of the settlement. A cleft half oak pole with treenail holes was also recovered from the south street (Trackway 3), most likely a roof timber as the holes were at the right distance to fasten rafters to the main frame and there was evidence for soot staining. An iron rotary key and padlock (F73153 ; F76185) were also recovered from this settlement, showing that some of the occupants of Settlement 5 felt there was a need to protect their property (Figs 6.15 and 6.16).

The medieval economy of Houghton was very likely a dual economy characterised by small-scale arable and pastoral farming and small-scale industrial activities combined with a woodland economy and possibly trade from the Great North Road. Agricultural activities, including crop cultivation and animal husbandry, would, however, have served as the primary occupation for the majority of the population. The cultivation of staple crops such as wheat, barley, oats, peas, and beans, which were commonly grown in medieval England, also took place in Houghton.

The environmental evidence from the samples recovered from Houghton indicated intensification in agricultural practices during the medieval period, represented by a rich assemblage of cereal grains including free-threshing wheat and six-row hulled barley (González Carretero 2024). The environmental evidence also suggests well-maintained agricultural soils and a diverse assortment of wild seeds, indicating a flourishing agricultural environment encompassing woodland management practices.

Animal husbandry held significant importance in the rural economy of medieval England. Livestock farming, involving the rearing of cattle, sheep and pigs, played a vital role in meeting the subsistence and economic needs of the population (Faine 2024b). The faunal assemblage discovered in Houghton primarily consisted of cattle, followed by sheep or goats and three complete pig remains, along with remains of domestic fowl. Evidence of fishing was characterised by eel and salmon remains. Woodland access would have provided additional areas for animal grazing and foraging. The animals provided not only a source of food but also raw materials, such as wool and hides, which were utilised in the production of textiles and leather goods.

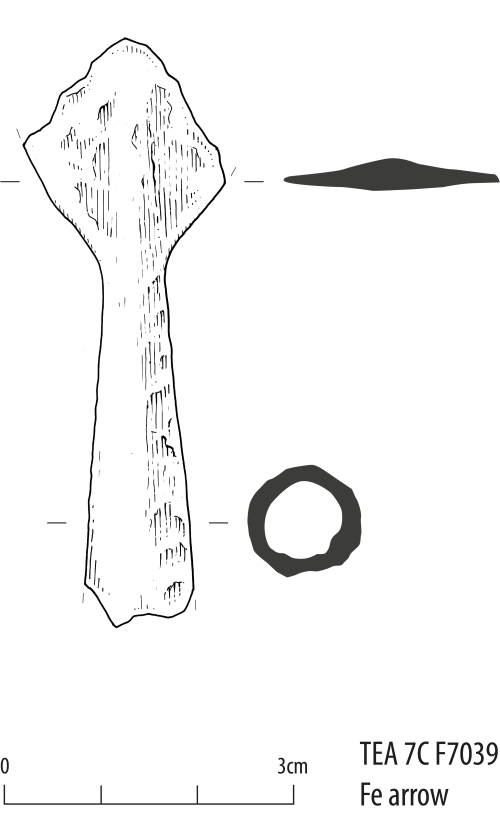

Hunting in medieval England was subject to strict regulations, with hunting rights typically restricted to the nobility. Forest laws governed hunting activities in royal and some non-royal forests and transgressions of these laws were severely penalised. However, evidence from Houghton's animal bone assemblage suggests that the villagers likely engaged in hunting within or near the local forest, as indicated by the remains of various wild game animals such as deer, rabbit, and hare. The presence of wild game animals in the faunal assemblage and the discovery of a metal arrowhead of a type used in hunting (F7039; Fig. 6.17), support this proposition.

Horse remains were limited in Houghton, likely serving as mounts and cart horses. Cattle were bred and utilised for on-site consumption as well as for export. The evidence suggests that cattle were processed and consumed within the settlement. Sheep, on the other hand, were primarily raised for wool production, as indicated by evidence of on-site breeding and the export of high-quality wool. Pigs were bred and slaughtered on-site, with evidence of butchery practices.

The concentration of animal bone in specific areas of the site, such as Linear Boundary 5 and the southern street (Trackway 3), suggests designated locations for the processing of animals. Structure 7BC.513 also stands out as a significant structure associated with animal processing, considering the substantial proportion of animal bone recovered from this specific area. The structure was interpreted as a possible butcher's shop (see Two special buidlings).

Documentary sources (EYRE Rolls of Huntingdon in Turner 1901) provide a connection between the hamlet of Houghton and Brampton Wood (as well as Harthay Wood), stating that the wood was said (by local people giving evidence to Justices during Pleas of the Forest in 1255) to have been common up to 1154. The king, the bishop of Ely and Henry de Hastings all had some interest in the timber and wood in Brampton Wood, but tenants probably had some access to wood and pasture (Carpenter 2008).

The archaeological evidence for this association of the hamlet to the nearby woods is limited as the majority of woodland resources utilised are biodegradable and have not survived.

Nevertheless, the significance of woodlands in the medieval economy cannot be overlooked. Timber served as a crucial resource for construction, shipbuilding, and tool production, while firewood played a primary role in domestic heating and energy generation. The demand for wood extended beyond these conventional uses. Industries such as ironworking relied on charcoal, while tanning and glass production depended on bark. The woodland economy catalysed various economic activities, fostering trade and craftsmanship. Although these activities might not be readily apparent in the archaeological record, certain archaeological features identified at Houghton could be interpreted as integral components of the woodland economy. For instance, the streets at Houghton likely facilitated timber exports. The western street (Trackway 4) probably served as the primary connection between the wood and the hamlet, while the northern street (Trackway 2) may have been dedicated to domestic trade. The southern street (Trackway 3), situated along the southern edge of the hamlet, might have facilitated the transportation of timber and other woodland products to the Great North Road for trade in distant markets.

Woodlands and royal forests provided not only land for assarting (during disafforestation or with payment of fees) but also pasture for various types of livestock. The concentrated presence of animal bone remains in Linear Boundary 5 and the southern street (Trackway 3), closer to Brampton Wood access, could indicate that the processing of meat products was carried out nearer the area where the animals were killed, perhaps for easy access to trade beyond the local area along the southern street (Trackway 3) as well as domestic consumption.

Furthermore, the production of charcoal and other fuels within forests and woodlands would have served both domestic activities and exportation, supplying landlords, manors, the king, or the broader market. The primary market for fuel was likely associated with fuel-consuming industries, with iron production potentially being the most significant (Birrell 1980, 97). Archaeological evidence of this activity can perhaps be found in the 'burnt pits' identified across Houghton.

At Houghton, the produced fuel would have met the needs of the local smithy and possibly the local nearby industries such as the smelting furnaces and smithy at Godmanchester (Webster and Cherry 1975, 259-60), as well as for domestic cooking, including smoking fish, meat and cheese. Documentary evidence suggests that the forest and woodland economy were closely intertwined with the local peasantry, as many peasants living in or near forests were employed, at least part-time, in forest industries (Birrell 1980, 92). It is reasonable to assume that a similar dynamic existed at Houghton.

The remains of the smithy found at Houghton indicates the presence of a blacksmith, although no specific historical evidence regarding a resident blacksmith has been discovered. It is reasonable to assume that the blacksmith would have fulfilled the community's needs for tools, repairs, domestic items, and possibly served the demands of travellers along the Great North Road, a major route at the time.

The medieval blacksmith played a pivotal role in society, being central to the medieval economy. They were skilled artisans responsible for forging iron and creating a wide range of metal goods. Blacksmiths produced tools and weapons essential for agriculture and warfare, as well as crafting household items, decorative objects, and conducting repairs. Their craftsmanship was highly valued, and they held respected positions within their communities, passing down their skills through apprenticeships and participating in local events and ceremonies.

The medieval blacksmith's workshop was a bustling centre of activity, typically situated in the peripheral part of the village or town or along a road. It served as a focal point where locals would gather to observe the blacksmith's work and seek their services. In Houghton, the smithy likely catered to travellers along the Great North Road, with convenient access via the northern street (Trackway 2).

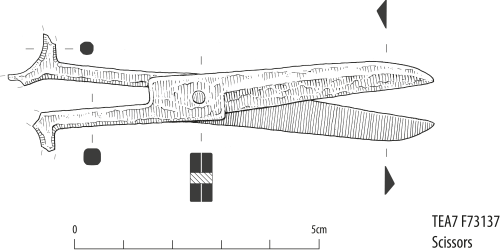

Other industrial activities are less clear and based on the assemblages of artefacts and archaeological evidence (Sillwood 2024c). The presence of specific artefacts, such as two stone spindle whorls (plus five from the subsoil) (F7171, F73278), an iron heckle tooth (F73022), and a pair of iron scissors (F73137; Fig. 6.18), supports the archaeological evidence of textile working. Additionally, the recovery of a lead weight (F72025 ) from the subsoil indicates some form of weighing and measuring, while the discovery of a punch and auger (F7160, F7358) implies woodworking activities. Documentary records suggest brewing was also an activity practised at Houghton, where in 1350 at least 18 brewers resided.

The absence of burials in these archaeological excavations hinders our understanding of the people who once inhabited the medieval settlements and villages. However, in the case of Houghton, both archaeological and documentary evidence offer valuable insights into the identity of its inhabitants.

According to the 1279 Hundred Rolls, Houghton was home to 34 individual tenants, with at least 20 of them occupying houses and associated buildings. These tenants owned lands totalling 240 acres of arable land and 37 acres of meadow. The exact details of pasture are not provided, as it would have involved shared grazing on commons, which couldn't be expressed in terms of acreage. It is worth noting that the villagers of Houghton had a uniform legal status as sokemen, meaning they paid cash rent, were not obliged to provide labour services, and fell under the jurisdiction of the lord of Brampton's court. The median rent they paid was 7d per acre per annum, which compares with an average of 3d per acre for free tenants in a sample of 60 Huntingdonshire villages, although the highest was recorded as 15d per acre (Kanzaka 2002, 611).

The status of the Houghton villagers as sokemen was uncommon, as many settlements in Huntingdonshire had a higher proportion of customary or servile tenants. Additionally, the Houghton tenants enjoyed the privilege of belonging to an 'ancient demesne' manor, which provided them with special legal procedures for land transfer. These tenants could seek protection from the king if their rents and services were increased, as seen in 1241-2 when they negotiated with the king for protection but were eventually forced by their lord to pay tallage. In response, they rebelled and reclaimed cattle seized by the authorities in 1242 and 1338. The Calendar of Patent Rolls from 1338-40 includes a list of individuals who participated in the 1338 tallage revolt. Among them, seven were residents of Houghton, including William Aley, who is mentioned in the 1350 Brampton court records as one of 18 brewers based in Houghton.

Another individual mentioned in the records is John Hicson, a young man who moved to Houghton from Ellington, less than 3km to the west, in 1447. This might be associated with Phase 4 of the archaeological evidence, which indicates limited new habitation on the site. The archaeological and artefactual evidence supports the notion that the inhabitants of Houghton were relatively poor and lacked significant social stratification. Most of the houses in the settlement were small, and the majority of landholdings were less than 8 acres. It is possible that this would not have been sufficient to support an average family although part-time participation in woodland activities might have offered further economic support.

The pottery assemblage from Houghton consisted mainly of unglazed St Neots and developed St Neots ware characterised by strictly utilitarian forms such as jars, bowls and jugs. Similarly, only a small number of artefacts associated with personal adornment were found, such as three copper-alloy buckles in stratified contexts, suggesting that luxury items were not commonly owned by the inhabitants owing to economic constraints. Though it may be that such items were efficiently recycled by the local smith.

The documentary evidence associated with royal and manor courts indicates that by the 13th century, surnames 'were fast replacing patronymics' (DeWindt 1980, 48) although they broadly still reflected some occupations. The name Webster, in association with Houghton, survives in the documentary records. This name, in fact, appears twice among the Houghton participants, in the 1338 rebellion.

The surname 'Webster' has its roots in England and originated during the Middle English period as an occupational surname for individuals involved in weaving although the name not only denotes the occupation of weaving but also reflects the social status and economic standing of those bearing the name. Weavers were esteemed members of their communities, playing a vital role in the medieval economy and often enjoying special privileges within guilds, which regulated the trade.

In 1350, a fulling mill was working at Brampton, finishing woollen cloth woven in the surrounding countryside (Hunts Archives Box 4/3A). Thus, in the case of Houghton, the historical documents, etymology of the name, and archaeological evidence align to suggest perhaps the presence of a Webster family engaged in textile production on-site.

The Hundred Rolls also list an individual named Woodward, living in Houghton in 1279 which could be an indication of an occupational name, suggesting in this case an association with the nearby woods.

Both the documentary and archaeological evidence suggest that the community at Houghton included farmers, herders, butchers, bakers, woodcutters (or other wood-associated craftsmanship) and individuals involved in food and drink preparation as well as textile production.

Houghton developed on the western edge of the territory of Brampton, c. 200m west of the Great North Road and this location must have played a role in its development. In medieval England, the road network played a crucial role in facilitating communication, trade, and transportation. These roads, commonly known as 'highways', formed the backbone of the medieval communication network, connecting various towns, villages, and cities across the country. Examining the development and significance of these medieval roads provides valuable insights into the socio-economic and political landscape of the era.

Medieval roads were primarily constructed to meet local transportation needs and were generally narrow and inadequately engineered by present-day standards (Hindle 2015, 45). Constructed using natural materials such as gravel, dirt, and clay, these roads lacked advanced engineering techniques. Consequently, they often exhibited uneven surfaces, were prone to erosion, and became muddy, making travel challenging and arduous. Nonetheless, despite their limitations, medieval roads played a pivotal role in connecting communities and facilitating trade and commerce.

Medieval roads supported economic activities, serving as major trade routes. They enabled the transportation of goods, including agricultural produce, manufactured goods, and other commodities, between towns and markets. An example of this at Houghton is the presence of pottery types from the St Neots and Huntingdon areas as well as Lyveden-Stanion pottery types from the west, suggesting trade movements north to south and east to west following the existing routeways. The accessibility of roads was crucial for the growth of local industries and markets, as it allowed merchants and traders to transport their goods to different regions. Moreover, roads served as vital links connecting towns and cities to ports, facilitating the movement of goods in and out of the country and promoting international trade. At Houghton, it would have favoured the trade in woodland goods such as timber.

Documentary evidence, such as the itineraries of Richard I, King John, Henry III, and Edward I, highlights the significant movement of people during this period. This included royal and military personnel as well as cattle drovers, particularly from the time of the Norman Conquest onwards (Stenton 1936, 4). An interesting example is the itinerary of William de Percehay, formerly the sheriff of York, who, in the summer of 1375, transported the ransom of David, the King of Scots, from York to London in six days (Stenton 1936, 17). William's convoy carried sacks of silver pennies and covered an average distance of 32 miles per day, totalling 192 miles. After safely delivering the cargo and spending a night in London, he returned to York in five days, travelling via Royston and Stamford along the Great North Road. This itinerary would have taken William in close proximity to Houghton, providing access to its amenities, including the local blacksmith, if needed.

The agricultural-focused activity across the A14 archaeological mitigation carried on into the post-medieval and modern periods. The majority of this evidence was represented by ridge-and-furrow cultivation remains, boundary ditches, fence-lines and parish ditches visible on the 1888 OS map, such as for example, the parish boundary between Godmanchester and Offord Cluny identified at River Great Ouse Landscape Block (Atkins and Douthwaite 2024).