Cite this as: West, E., Christie, C., Moretti, D, Scholma-Mason, O. and Smith, A. 2024 A Route Well Travelled. The Archaeology of the A14 Huntingdon to Cambridge Road Improvement Scheme, Internet Archaeology 67 (Monograph 32). https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.22

The A14 landscape witnessed a rapid expansion in settlement activity during the Iron Age, marking a clear departure from the preceding pattern of low-visibility, low-density settlement. Iron Age settlements were recorded in all Landscape Blocks, with a wide range of settlement forms represented (Fig. 3.1; Table 3.1). Early Iron Age (800-350 BC) activity was, however, far more limited, comprising dispersed evidence with settlement only identified at Fenstanton Gravels and Conington. This is in marked contrast to the middle Iron Age (350-100 BC) which saw a notable peak in settlement numbers, alongside widespread changes in settlement form and agricultural strategies. Many of these showed evidence for multiple phases of development reflecting the changing roles or needs of the settlements. A high proportion of settlements seemingly did not persist much (or at all) into the late Iron Age (100 BC-AD 50), with the nuances of this presenting a complex pattern of settlement development (Fig. 3.2).

Use top bar to navigate between chapters

A total of 22 settlements were recorded, spanning the early to late Iron Age, displaying a variety of characteristics (Table 3.1). The range and diversity of settlements recorded throughout the Iron Age reflects the variety of agricultural activities taking place as well as wider societal changes. Past studies of Iron Age settlements have often focused on their classification into a range of categories, which at their broadest level comprised open and enclosed forms (Brudenell 2020; Knight 1984). However, the distinction between enclosed and unenclosed sites is often unclear and a focus on classification can come at the expense of understanding the less archaeologically visible aspects of settlement organisation and connection. As emphasised in recent studies the sheer diversity of settlement forms tends to defy typological approaches to settlement (Dawson 2000a, 109; Clay 2002; Evans et al. 2008; Wright et al. 2009; Medlycott 2011; Huisman 2019; Knight and Brudenell 2020). Consequently, settlement organisation across the A14 has been considered at a broader landscape scale, with a focus on highlighting hubs of activity, ideas of interconnectivity and wider landscape management.

At the western extent of the scheme, two settlements were identified at Alconbury (A1 and 2) spanning the middle to later Iron Age, while another (A4) had probable late Iron Age foundations, but was mostly Roman in date and is discussed in Chapter 4. Further to the south-east, the landscape extending from Alconbury to the River Great Ouse comprising Brampton West, Brampton South and West of Ouse, provides a key focus for Iron Age settlement development, with a total of nine settlements recorded. At Brampton West five settlements of varying form were revealed (BW 1, 2, 100, 102 and 202) with a further two recorded at Brampton South (BS 1 and 2) to the east. The two settlements identified at West of Ouse (WOO1 and 2) represent more dispersed activity extending towards the river. To the east of the river, two settlements were identified at River Great Ouse (RGO1 and 2), although one of these (RGO2) was heavily truncated by the establishment of a significant Roman settlement and a late Roman villa (see Chapter 4). Within the Fenstanton Gravels Landscape Block four settlements were recorded (FG1-4) and are probably contemporary with the single settlement identified at Conington (C3), and those recorded at the Dairy Crest and Cambridge Road sites just to the north at Fenstanton (Ingham 2022; Fig. 3.3). At the eastern end of the scheme at Bar Hill four settlements were recorded (BH1, 3-5), comprising a diverse range of settlement types, which are in turn linked to a wider area of settlement excavated to the north and east of Bar Hill at Northstowe and Longstanton (Evans and Dickens 2002; Evans and Mackay 2004; Evans et al. 2005; Patten and Evans 2005; Knight and Mackay 2007; Aldred and Collins forthcoming; Fig. 3.3).

This chapter opens with an examination of the development of settlements from the early to late Iron Age, exploring key themes and patterns as well as providing commentary on the available chronological data. This is followed by a consideration of the nature of settlement organisation and the various activities taking place within the sites, through a critique of the evidence for settlements, structures, and landscapes, as well as the varied socio-economic and ritual activities associated with the period. Importantly, the extensive and wide-ranging excavations undertaken across the A14 not only afford the opportunity to examine the settlements themselves but also to consider their relationship with their wider agricultural hinterlands and neighbouring settlements. While a number of these sites are discussed in brief, the broader networks across the A14 landscape are more fully considered in the wider synthesis of the Iron Age presented in the landscape monograph (Billington and Brudenell forthcoming).

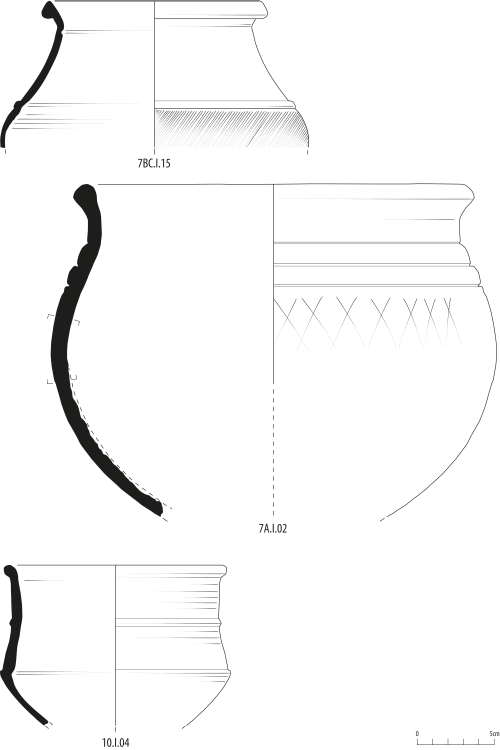

Despite the relative abundance of evidence for Iron Age settlement across the A14, gaining a nuanced understanding of settlement development is hampered by several issues around the dating and phasing of features. This is a widely acknowledged problem within Iron Age studies relating to the difficulties in distinguishing chronologically diagnostic finds and ceramics (Hamilton et al. 2015; Percival 2024i), compounded by the often limited resolution provided by radiocarbon dating owing to the Hallstatt plateau (800-400 BC). A total of 55 samples were successfully radiocarbon dated from Iron Age features, with the resulting dates clustering from 380-100 cal BC (Table 3.2). The pottery assemblages often provided limited chronological resolution owing to the longevity of techniques and styles, with the notable exception of Aylesford-Swarling wares. These were in use from c. 100 BC and were characterised by a range of wheel-made tall urn-shaped vessels with pedestaled bases, a range of grooved and cordoned bowls, butt beakers and lid-seated jars (Percival 2024i; Fig. 3.4).

| Landscape Block | Group | Context | Sample | Material Dated | Labcode | δ13C relative to VPDB | Radiocarbon Age BP | Radiocarbon Date (95.4% Probability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alconbury | Ditch 5.116 | 50367 | 50367 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-91495 (GU53776) | -21.7 | 2205±24 | 370-170 cal BC |

| Alconbury | Pit Group 5.290 | 51876 | 51876 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92680 (GU54234) | -22.3 | 2145±24 | 360-50 cal BC |

| Alconbury | Ditch 5.159 | 53850 | 53850 | Animal Bone: horse | SUERC-92681 (GU54235) | -21.8 | 2168±24 | 360-100 cal BC |

| Alconbury | Ditch 5.33 | 58027 | 58027 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92682 (GU54236) | -22.1 | 2174±24 | 360-120 cal BC |

| Alconbury | Roundhouse 5.63 | 51883 | 51883 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92683 (GU54237) | -21.7 | 2127±24 | 350-50 cal BC |

| Alconbury | Ditch 5.1 | 58047 | 58047 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92684 (GU54238) | -21.7 | 2275±21 | 400-210 cal BC |

| Brampton West | Ditch 7.319 | 738154 | 73831 | Charred Cereal grains: Triticum spelta | SUERC-91054 (GU53684) | -22.8 | 1961±24 | 40 cal BC - cal AD 130 |

| Brampton West | Pit Group 10.230 | 107101 | 10638 | Charred Cereal grains: Triticum sp. | SUERC-91143 (GU53696) | -21.2 | 2235±22 | 390 -200 cal BC |

| Brampton West | Structure 7.8 | 731462 | 731462 | Animal Bone: sheep/goat | SUERC-91465 (GU53753) | -22.1 | 2006±23 | 50 cal BC - cal AD 80 |

| Brampton West | Pit Group 7.7 | 730848 | 730848 | Animal Bone: sheep/goat | SUERC-91466 (GU53754) | -21.8 | 2161±24 | 360 -100 cal BC |

| Brampton West | Roundhouse 7.311 | 736570 | 736570 | Animal Bone: sheep/goat | SUERC-91476 (GU53762) | -21.8 | 2057±26 | 160 cal BC - cal AD 20 |

| Brampton West | Ditch 7.44 | 733386 | 733386 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-91482 (GU53766) | -21.8 | 2019±26 | 100 cal BC - cal AD 70 |

| Brampton West | Ditch 10.257 | 103160 | 103160 | Animal Bone: sheep/goat | SUERC-91496 (GU53777) | -21.8 | 2022±23 | 90 cal BC - cal AD 70 |

| Brampton West | Pit 103162 | 103163 | 103163 | Animal bone: sheep/goat | SUERC-91502 (GU53781) | -21.4 | 2056±23 | 160 cal BC - cal AD 20 |

| Brampton West | Ditch 10.334 | 105123 | 105123 | Animal Bone: sheep/goat | SUERC-92686 (GU54241) | -21.5 | 1998±24 | 50 cal BC - cal AD 110 |

| Brampton West | Mound 10.167 | 600719 | 600719 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92691 (GU54243) | -21.3 | 1954±24 | 40 cal BC - cal AD 130 |

| Brampton West | Mound 10.167 | 601495 | 601495 | Animal Bone: horse | SUERC-92694 (GU54247) | -22.4 | 2128±24 | 350-50 cal BC |

| Brampton West | Mound 10.167 | 601512 | 601512 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92695 (GU54248) | -22 | 2101±24 | 200-40 cal BC |

| Brampton West | Mound 10.167 | 601030 | 601030 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92696 (GU54249) | -22.4 | 2101±24 | 200-40 cal BC |

| Brampton West | Pit Cluster 10.585 | 103999 | 103999 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92700 (GU54250) | -22.2 | 2032±21 | 100 cal BC - cal AD 60 |

| Brampton West | Inhumation Burial 7.3 | 720506 | - | Human bone: - | SUERC-97729 (GU57414) | -20.2 | 2154±25 | 360-50 cal BC |

| Brampton West | Inhumation Burial 7.151 | 731503 | - | Human bone: - | SUERC-97731 (GU57416) | -20.8 | 2138±25 | 350-50 cal BC |

| Brampton West | Inhumation Burial 7.664 | 767007 | - | Human bone: - | BETA-637561 | -19.1 | 2040±30 | 150 cal BC-cal AD 60 |

| Brampton West | Cremation Burial 10.62 | 604182 | - | Human bone: - | SUERC-97737 (GU57419) | -25.8 | 1976±25 | 40 cal BC - cal AD 120 |

| Brampton West | Ditch 7.6 | 730976 | 7340 | Charcoal: cf. Ilex aquifolium | SUERC-98094 (GU57464) | 26.1 | 2040±28 | 150 cal BC - cal AD 60 |

| Brampton West | Ditch 7.219 | 386094 | 38589 | Charred Cereal grains: Hordeum vulgare | SUERC-91385 (GU53720) | 2095±25 | 180-40 cal BC | |

| Brampton South | Pit Cluster 13.48 | 132325 | 13255 | Charred Cereal grains: Hordeum sp. | SUERC-91456 (GU53709) | -24.8 | 2199±24 | 370-170 cal BC |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Post-hole | 271057 | 27024 | Waterlogged wood: | SUERC-75284 (GU45479) | 2505±34 | 790-510 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Waterhole 29.2 | 290030 | F29087 | Waterlogged wood: | SUERC-75285 (GU45480) | 2441±34 | 760-400 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Waterhole 29.3 | 290586 | F29034 | Waterlogged wood: Birch | SUERC-75286 (GU45481) | 2369±34 | 720-380 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Pit | 270968 | 27063 | Burnt animal bone: | SUERC-75288 (GU45483) | 2507±34 | 790-510 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Inhumation Burial 28.610 | 281064 | - | Human bone: Tibia | SUERC-85552 (GU50640) | 2247±24 | 390-200 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Inhumation Burial 28.432 | 281210 | - | Human bone: Human- L Femur | SUERC-85553 (GU50641) | 2246±24 | 390-200 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Cremation Burial 28.538 | 285607 | 28654 | Human bone: - | SUERC-85558 (GU50643) | 2145±24 | 360-50 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Structure 28.489 | 281055 | 28220 | Charcoal: Pomoideae sp. | SUERC-91386 (GU53721) | 2264±25 | 400-200 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Ditch 28.63 | 790016 | 79003 | Charcoal: Ilex aquifolium | SUERC-91391 (GU53723) | 2048±25 | 160 cal BC - cal AD 30 | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Roundhouse 28.134 | 281649 | 28252 | Charcoal: Pomoideae sp. | SUERC-91392 (GU53725) | 2309±25 | 410-230 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Cremation Burial 31.75 | 310135 | 31006 | Cremated Human Bone: - | SUERC-92291 (GU54160) | -21.2 | 2033±30 | 150 cal BC - cal AD 70 cal |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Ditch 28.340 | 780823 | 780823 | Animal Bone: sheep/goat | SUERC-92376 (GU54186) | -21.9 | 2176±28 | 370-110 cal BC |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Roundhouse 31.40 | 311127 | 311128 | Animal Bone: horse | SUERC-92381 (GU54190) | 2219±28 | 390-190 cal BC | |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Inhumation Burial 28.574 | 280801 | 280801 | Human Bone: - | SUERC-92755 (GU54646) | -20.2 | 2033±24 | 110 cal BC - cal AD 70 |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Pit Group 29.68 | 290571 | 29120 | Cereal grain: Hordeum vulgare | SUERC-98084 (GU57457) | -23.5 | 2386±28 | 720-390 cal BC |

| Fenstanton Gravels | Roundhouse 29.10 | 290850 | - | Animal bone- calcaneum: cattle | SUERC-98149 (GU 57559) | -22.3 | 2173±28 | 360-100 cal BC |

| Conington | Waterhole-Well 33.140 | 331827 | - | Wood: Oak | SUERC-92742 (GU54435) | -26.2 | 2281±17 | 400-230 cal BC |

| Bar Hill | Ditch 38.219 | 386094 | 38589 | Charred Cereal grains: Hordeum vulgare | SUERC-91385 (GU53720) | - | 2095±25 | 180-40 cal BC |

| Bar Hill | Ditch 41.81 | 410767 | 41056 | Charred root: non-oak | SUERC-91394 (GU53727) | - | 2285±25 | 410-210 cal BC |

| Bar Hill | Ditch 41.8 | 410094 | 41016 | Charred Cereal grains: Triticum sp. | SUERC-91395 (GU53728) | - | 1930±25 | cal AD 20-210 |

| Bar Hill | Ditch 38.83 | 384818 | 384818 | Animal bone: sheep | SUERC-91504 (GU53783) | - | 2179±26 | 370-150 cal BC |

| Bar Hill | Ditch 38.176 | 381772 | 381772 | Animal bone: sheep | SUERC-91505 (GU53784) | - | 2050±26 | 160 cal BC - cal AD 30 |

| Bar Hill | Inhumation Burial 38.74 | 381833 | 381833 | Human Bone: - | SUERC-91608 (GU53840) | - | 2178±26 | 370-120 cal BC |

| Bar Hill | Inhumation Burial (381956) | 381956 | 381956 | Human Bone: - | BETA-63492 | 2050±26 | 160 cal BC - cal AD 30 | |

| Bar Hill | Inhumation Burial 38.135 | 383075 | 383075 | Human Bone: - | SUERC-91609 (GU53841) | - | 2089±26 | 180-1 cal BC |

| Bar Hill | Ditch 41.2 | 410057 | 410057 | Animal Bone: cattle | SUERC-92371 (GU54177) | -21.7 | 2034±28 | 150 cal BC - cal AD 70 |

| Bar Hill | Pit 383971 | 383973 | 38535 | Wood: Oak | SUERC-92743 (GU54436) | -25.4 | 2259±21 | 400-200 cal BC |

| Bar Hill | Inhumation Burial 38.318 | 380391 | - | Human bone: - | SUERC-97751 (GU57438) | -20.1 | 2032±25 | 110 cal BC - cal AD 70 |

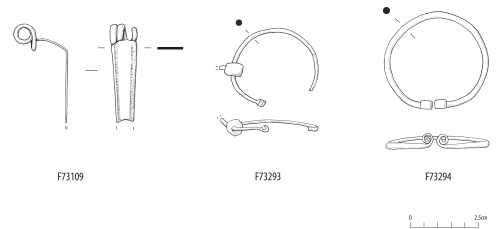

The presence or absence of Aylesford-Swarling wares provides a useful reference point for identifying the transition into the late Iron Age. Unlike the local traditions of hand-built pottery, including Scored Ware and East Midlands ware, Aylesford-Swarling wares tend to have a fairly tight date range (c. 100 BC- AD 70), contrasting with broad ranges appended to other local traditions (typically 350-50 BC) (Elsdon 1992; Percival 2024i). Two caveats though need to be attached to this general hypothesis; the first being that hand-built wares persist into the later Iron Age and beyond, secondly the presence or absence of these objects could reflect social rather than temporal factors. Indeed, the relative conservativeness of Iron Age pottery can be partly attributed to its largely utilitarian role in the Iron Age, with changes in form occurring in the 1st century BC being keyed into wider social changes (Pitts 2005; Sutton et al. 2024). These vessels are often associated with broader changes in material culture and society, notably the development of a distinct range of funerary practices, and a general uptake in the use of brooches (Mackreth 2011), and coinage (see Cunliffe 2005 for overview). With these caveats in mind the presence or absence of Aylesford-Swarling wares does nonetheless provide a useful yardstick by which to gauge the relative chronology of the various Iron Age sites, alongside other artefacts and the suite of radiocarbon dates.

In the following section, the broad chronology and key features of the recorded settlements are outlined. This discussion opens with a consideration of the nature of the evidence for settlement during the early Iron Age before examining the expansion of settlements that took place in the 4th century BC. The final section considers the evidence for settlement aggregation and contraction during the late Iron Age. Detailed stratigraphic descriptions and discussions by phase can be found within the individual Landscape Block reports. While this section touches on aspects of the early to mid-1st century AD, the transition into the Roman period is considered more fully in Chapter 4.

The transition from the Bronze Age into the Iron Age is typically seen as involving the advent of new materials, societal transformation, and the intensification of agriculture (Haselgrove and Pope 2007). The period also witnessed significant environmental changes, with the development of an increasingly open environment with rising water levels from c. 800 BC (French and Heathcote 2003, 85; Evans et al. 2016). Iron Age settlements of this period typically, like their Bronze Age counterparts, are characterised by low visibility remains, hampering identification (Haselgrove et al. 2001; Haselgrove and Pope 2007). Where recorded, early Iron Age settlements across Cambridgeshire typically comprise small-scale 'open' settlements, containing a repertoire of pits, post-holes, wells and four-poster structures, such as at Milton landfill and Park and Ride sites, Cambridge (Y. Phillips 2015), Trumpington (Patten 2012) and Clay Farm Cambridge (Phillips and Mortimer 2012). While the denser 'pit cluster settlements' as typified by Trumpington are generally restricted to southern Cambridgeshire on the chalk (Evans et al. 2018, 119), there is mounting evidence (e.g. Cambridge Road, Ingham 2022) for the presence of smaller scale settlements extending to the west, which appear to be associated with seasonal activities.

The nature of the early Iron Age activity from the A14 fits within this pattern, taking the form of disparate features, comprising pits, ditches, and possible structures, although only in two cases did these define settlements (Table 3.1 XLSX). At the western end of the scheme limited evidence for early Iron Age activity, in the form of pits containing early Iron Age pottery, was recorded at Brampton West. However, more substantial early Iron Age activity was recorded at Thrapston Road located c. 0.5km to the north-east of Brampton West. Early Iron Age features, including large groups of post-holes defining four- to six-post structures and a post-built roundhouse, were recorded spread across an area measuring c. 200 × 200m (4 hectares; Reid and Atkins 2019). The layout of the features at Thrapston Road is comparable to the two early Iron Age settlements recorded within the central section of the A14 at Fenstanton Gravels and Conington.

The settlement at Conington 3 comprised a dispersed collection of pits, small ditches, waterholes, and a possible structure. These features were located within and around a Bronze Age field system, possibly suggesting a deliberate referencing or reoccupation of the feature, although the precise chronology and relationship of the settlement and field system is uncertain (Fig. 3.5). The two large waterholes provided evidence of the local environment, with an abundance of seeds indicative of nutrient-enriched, cultivated ground (Fosberry 2024; Wallace and Ewens 2024). The features at Conington 3 potentially represent occupation scatter or peripheral activity associated with seasonal, sporadic or short-lived agricultural activity as opposed to permanent settlement (Brudenell 2021; White et al. 2024).

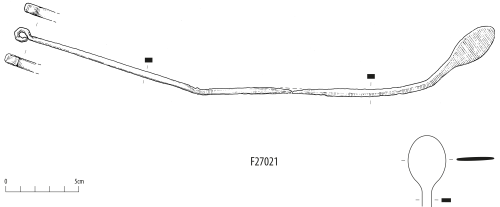

In contrast,the early Iron Age features at Fenstanton Gravels, located c. 1.2km to the north-west, indicate a greater concentration of activity and transformation of the site. At Fenstanton Gravels 2 early Iron Age settlement was concentrated at the eastern extent of the Landscape Block (TEA 29), comprising a possible roundhouse, pits, structures, waterholes and a droveway/field ditches extending north (Fig. 3.6). The roundhouse, roundhouse 29.10, was located adjacent to the droveway/field ditches, which extend for over 200m with 13 four-post structures located at its northern extent. The presence of over a dozen four-poster structures probably represent the remains of raised granaries or drying platforms, associated with the cultivation of wheat (Triticum spp.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare), as evidenced by the environmental remains (Hunter Dowse and Turner 2024). Barley appears to have been the main crop grown during this period, contrasting with the middle to late Iron Age, when wheat became the predominant crop. Surrounding the structures was a group of six waterholes from which a rich artefactual assemblage was recovered including a notable collection of waterlogged wood. This included the remains of an alder plank screen or fence, two ladders (F29087 and F29117), a piece of twisted withy rope (F29060), a Y-crotch section of birch (F29034) and an oak stirring paddle (F29109) (Fig. 3.7). Ladder F29087 was radiocarbon dated to 760-400 cal BC (SUERC-75285) with the Y-crotch section of birch dated to 720-380 cal BC (SUERC-75286), overlapping with the final Bronze Age notched log ladders found at Striplands Farm to the west (Patten and Evans 2005; Evans et al. 2011) (Fig. 3.7). Also of note is the presence of an iron spud (F29023) from the fill of waterhole 29.2; these tools are typically associated with agricultural activities (Humphreys and Marshall 2024b). The environmental assemblages and pollen analysis indicate the presence of damp grassland, with the waterholes representing pastoral activity and the management of livestock. The presence of dwarf pond snails is indicative of wet grassland or the margins of a water body subject to occasional flooding.

To the east of Fenstanton Gravels 2, further early Iron Age activity was recorded at TEA 27 consisting of a four-poster structure and eight pits, one of which contained a nationally important Iron Age poker-shovel (F27020 and F27021) , associated with metalworking (Fig. 3.8). The industrial waste from the site comprised a small assemblage (756g) of smithing hearth cakes, suggesting small-scale iron smithing during the early Iron Age. Further pits with early Iron Age pottery were noted at TEA 28, but these appear to be unrelated to activity at Fenstanton Gravels 2, located on the east side of contemporary gravel streams. At Albion Archaeology's Cambridge Road, Fenstanton, excavations to the north of the A14's Conington and Fenstanton Gravels Landscape Blocks, a sequence of intercutting pits, a trackway, a single four-post structure and up to four cremation burials were dated to the early Iron Age (Ingham 2022, 16; Fig. 3.3). Further settlement evidence has been identified at Church Farm, Fenstanton, with a late Bronze Age/early Iron Age circular enclosure, a linear droveway, a possible hearth and several pits (Carlyle and Chapman 2002; ECB2070), while an extensive spread of cropmarks to the north of Conington suggest further settlement activity (MCB11492), although the precise dating of these is unclear.

Overall, it is clear, as is typical for most of the region, that the earliest Iron Age of the A14 is characterised by low visibility, unenclosed settlements. The ephemeral nature of most of these could be indicative of seasonal patterns of occupation and use of fertile grasslands for stock grazing reflecting a persistence of earlier settlement patterns (see Chapter 2). The high number of four-poster structures at Fenstanton Gravels 2 may indicate a shift towards more permanent forms of occupation, pre-empting the wider expansion of settlement in the middle Iron Age. This mix of seasonal and more permanent settlement is observed across the Cambridgeshire region, with larger aggregate 'pit settlements' being noted, such as at Trumpington Meadows where in excess of 750 pits were recorded (Patten 2012; Evans et al. 2018, 126). These more intensive 'pit settlements' are typically not found on the clay uplands to the north and west of Cambridge, partly reflecting prevailing geological conditions (Evans et al. 2018, 119). The potential permanence of settlement at Fenstanton Gravels 2 could be related to the expansion of arable cultivation within this part of the A14, partly motivated by the suitability of the local soils. These settlements at Fenstanton Gravels and Conington are located within areas of high fertility or free-draining soils, with the settlement at Fenstanton Gravels 2 being located within a large band of high fertility soils suited to arable cultivation (Fig. 3.9). A similar pattern is noted at Thrapston Road (Reid and Atkins 2019) and at Striplands Farm, suggesting that the location of sites may have been informed by a degree of local knowledge about underlying ground conditions (Patten and Evans 2005; Evans et al. 2011, 42). From the 4th century BC onwards a wider range of soils were quickly brought under cultivation, giving rise to a dramatic and unprecedented increase in the number of recorded settlements.

The middle Iron Age witnessed a 'settlement boom' with settlements identified at all A14 Landscape Blocks, coinciding with a rapid expansion into the region's clay uplands (Evans et al. 2008, 179, 193). This is a pattern witnessed across much of lowland Britain, with a dramatic shift in the visibility and number of recorded settlements (Sherlock 2012; Heslop 2020; Brudenell 2021; Willis 2022). On the A14, this expansion appears to be reflected in the environmental data, which shows an overall reduction in woodland in the middle-late Iron Age (Grant 2024a-h). Woodland decline during this period is often linked to the expansion of agricultural activity onto poorer soils and settlement into previously marginal areas (Grant et al. 2011). Pin-pointing the commencement of settlement in the middle Iron Age on the A14 presents a challenge but also an opportunity to test the seeming lack of continuity from the early Iron Age. Archaeologically, the majority of settlements across the A14 appear to begin in the middle Iron Age from c. 350 BC, with a total of 17 settlements established during this period (Table 3.1, Figs 3.2 and 3.10). Numerous settlements displayed evidence for development throughout the middle Iron Age as enclosures were defined, remodelled and areas of domestic activity established. The duration of activity and variable patterns of decline reveal insights into the complexities of this process of 'colonisation', the mechanics of which will be more closely examined in the final section of this chapter.

At the north-western end of the scheme two settlements were recorded at the southern end of the Alconbury Landscape Block, bounded by the Ellington Brook to the south, which appears to have partly influenced the layout of the settlements (Fig. 3.11). This close positioning of the settlement on a stream or river is echoed at several other sites across the A14, including at Brampton West 1, and within the wider region including at Scotland Farm, Dry Drayton (Callow Brook; Abrams and Ingham 2008) and Loves Farm, St Neots (Fox Brook; Hinman and Zant 2018; Abrams and Ingham 2008). There was no evidence of early Iron Age (800-400 BC) activity at Alconbury, with the ceramic assemblage and the small number of radiocarbon dates from Alconbury 1 supporting a middle Iron Age date from the 4th to 1st centuries BC (Table 3.1; Rebisz-Niziolek and Hudak 2024a; Percival 2024i). Alconbury 1 appeared to develop around 350 BC and comprised an extensive boundary ditch with a co-axial field system and enclosures orientated along its length. As indicated by the cropmark data it is probable that this boundary continues as Linear Boundary 2, which formed the spine of Alconbury 2, serving to connect these two settlements (Fig. 3.11). The cropmark data also indicate the presence of a series of enclosures at the southern end of the U-shaped boundary, although the relationship of these to the boundary is uncertain.

Alconbury 2, based on its relationship to Linear Boundary 2, was established at a slightly later date than Alconbury 1 and potentially outlived it. As at Alconbury 1, the majority of the settlement activity took place to the west of the area delimited by the boundary, with the earliest phases comprising a series of conjoined enclosures and roundhouses. One structure, roundhouse 5.63, had a complete vessel placed upside down into a centrally located pit, suggestive of a 'closure' deposit (see Placed deposits). The second phase of Alconbury 2 was defined by a rectilinear enclosure system established over much of the middle Iron Age settlement. The small number of radiocarbon dates and the presence of sherds from La Tène style decorated vessels tentatively suggest activity extending into the 1st century BC but provide little clarity as to the date of transition. The overall dating of this field system is uncertain but does appear to suggest a shift in the location of the settlement focus. This could have been towards the north, where evidence for 1st century AD occupation was noted at Alconbury 4, although only a small area of this settlement was uncovered (see Chapter 4). The 'abandonment' of this area could reflect continued issues with seasonal flooding, which also appeared to occur at Brampton West 1, c. 1km to the south.

The middle Iron Age activity at Brampton West extended for over 1km, comprising four defined settlement areas. Brampton West 1 was the northernmost of the Brampton West settlements, being established around the 4th century BC, just to the north of a large palaeochannel. This channel formed part of a wider network of channels located across the flat land at the base of the slope (Fig. 3.12). The presence of these channels undoubtedly influenced the location of the Iron Age settlements within this block. The middle Iron Age phase of Brampton West 1 comprised a dense network of at least four enclosures with scattered boundaries extending across the area (Fig. 3.12). The enclosures, like those at Alconbury 2, appear to have been employed for a mix of domestic occupation and as stock enclosures, with the area to the east perhaps employed as pasture or arable fields (explored in more detail in the following sections). It is possible that these were also located to the south of the palaeochannels extending towards Brampton West 100.

A more constrained range of features was recorded at Brampton West 100, comprising a north-east to south-west aligned boundary ditch and a pair of enclosures 0.175km to the east of these ditches (Fig. 3.13). A single inhumation burial (7A.3), dated to 360-50 cal BC (SUERC-97729; Table 3.2), was located in the south-western corner of the Landscape Block, and is one of a number of articulated middle Iron Age burials recorded from across the scheme (see 'The dead'). The ceramic assemblage from an isolated pit (720642) included two small vessels, deposited broken but carefully arranged alongside a complete saddle quern potentially reflecting a deliberate deposit (as explored in 'Placed deposits') (Fig. 3.14). The vessels were large versions of slack-shouldered jars with characteristics suggestive of an early or middle Iron Age date c. 600-200 BC (Sutton and Rebisz-Niziolek 2024). While the assemblage from a single isolated pit does not definitively date the commencement of the settlement it does raise the potential for earlier activity preceding the main phase of settlement.

Contrasting with the relative dearth of features at Brampton West 100, Brampton West 102 just to the south comprised an extensive series of ditches, trackways, roundhouses, and enclosures (Fig. 3.13). These were broadly concentrated in the north-western and south-eastern parts of the settlement, defining separate settlement foci. Beyond these areas there was a range of scattered pits and various ditches, as well as a probable cemetery (Cemetery 102) forming part of the wider spread of activity associated with the settlement. Taken collectively, the ceramic assemblage, which included middle Iron Age East Midlands Scored Ware and East Anglian Plainware, may indicate a commencement of occupation prior to the introduction of Aylesford-Swarling wares in the 1st century BC (Sutton and Rebisz-Niziolek 2024).

Brampton West 202 was located at the southern extent of the Landscape Block and along with the initial phases of Brampton West 100 could represent the earliest Iron Age settlement within the block. The settlement covered an area of c. 5ha comprising a field system, enclosures and possible structures (Fig. 3.15). The pottery assemblage was dominated by hand-built pottery of East Midlands Scored Ware/East Anglian Plainware Type, suggesting activity during the 3rd to 1st centuries BC prior to the large-scale adoption of Aylesford-Swarling pottery (Sutton and Rebisz-Niziolek 2024). Unlike the other Brampton West settlements, there was no evidence for continuation into the 1st century BC. The activity at Brampton West 202 is probably contemporary and linked to the two middle Iron Age settlements uncovered at Brampton South located 200m to the east.

Activity at Brampton South comprised two discrete areas of settlement, although as at Alconbury 2 it is probable these were contemporary and interconnected settlements (Fig. 3.16). The earliest phase of the southernmost settlement, Brampton South 2, was based around Linear Boundary 3, which respected the late Bronze Age-early Iron Age pit alignment. To the north of the boundary was an enclosure system and a series of roundhouses lay to the south (Fig. 3.17). The final phase comprised the setting out of a rectilinear field system, echoing the phases of development at Brampton South 1, 0.27km to the north-west. At Brampton South 1 the earliest phases of the settlement comprised a pair of parallel ditches on a north-north-east to south-south-west alignment, possibly the remnants of a trackway (Fig. 3.16). The precise dating of this feature is uncertain, but both ditches appear to fall out of use around the same time, being succeeded by a new settlement focus to the south. As at Brampton South 2, the settlement was arranged on a north-west to south-east alignment. The settlement focus to the north of the linear boundary comprised a series of wells and waterholes alongside several roundhouses and ditches, which in its third phase were succeeded by a pair of enclosures. It is possible that during the middle Iron Age there was a contraction in settlement activity with the focus of domestic activity being located within Brampton South 2, as indicated by the higher quantities of pottery. The precise chronology of this change is unclear, but the absence of later artefact types, notably wheel-thrown pottery, suggests the settlement did not extend into the 1st century BC.

The final phase of activity at Brampton South was marked by the setting out of a field system just to the north, which continued to respect the alignment of the earlier settlement phases. Taken as a whole, the evidence from the Brampton West and South Landscape Blocks suggests a fairly extensive, albeit dispersed, pattern of settlement, characterised by linear boundaries and enclosure systems, with areas of pasture or arable fields between. At a broad level these settlements appear to be contemporary although it is apparent that within this there are subtle shifts in patterns of occupation, with some areas, such as at Brampton South, seeing a possible contraction in activity. The probable end date of the settlements at Brampton South overlaps with the expansion of the settlements at Brampton West to the north and may suggest a shift of settlement to the north.

During the middle Iron Age only very limited activity was identified at West of Ouse, 0.39km to the south-east, comprising dispersed ditches, an enclosure, pits and post-holes (see Fig. 3.24). It is possible that this area acted as a transitional zone between the settlements at Brampton West and the River Great Ouse. The activity at West of Ouse can also been seen as part of a north to south aligned zone of activity, extending south along the valley of the River Great Ouse, with Buckden and Offord Cluny 0.5km to the south and a further cluster of Iron Age activity around Little Paxton Quarry (Jones 2000; Fig. 3.3). In essence the sites at both West of Ouse and River Great Ouse can be seen as forming a 'T-junction', with what was probably a key routeway through the landscape (Chapter 2). The middle Iron Age activity at River Great Ouse 2 was defined by extensive linear boundaries with adjoining enclosures (Enclosure 4 & 5; Fig. 3.10). Enclosure 4 defined an area 125m² with a 5.5m wide entranceway to the north-east. Two possible roundhouses were identified within the enclosure with middle Iron Age pottery, fired clay and animal bone recovered from the enclosure ditch. Enclosure 4 adjoined a boundary ditch, which was recorded on a north-west to south-east alignment for c. 0.5km. A further boundary ditch extended to the east and appeared to link Enclosure 4 to Enclosure 5. The ditches within Enclosure 5 seem to define paddocks or stock enclosures potentially functioning as a central point or gathering place, with the multiple boundaries directing movement towards the enclosure. Middle Iron Age activity at River Great Ouse extended to the east, with a roundhouse, enclosures and scattered pits identified at River Great Ouse 1. The majority of the pottery assemblage is handmade dating from c. 350-50BC, with no evidence for wheel-made ware or transitional pottery (Percival and Lyons 2024). It is possible that the absence of late Iron Age activity could, as at Brampton South, reflect a contraction of settlement, or potentially a process of settlement drift, with activity lying beyond the A14 corridor.

Turning to the central section of the scheme, settlement remains were recorded at Fenstanton Gravels and Conington. As highlighted previously these sites are notable for their early Iron Age settlements, contrasting with the low levels of activity recorded elsewhere along the A14. During the middle Iron Age there was a significant expansion in activity, with four settlements recorded at Fenstanton Gravels and one at Conington (Table 3.1; Fig. 3.2). Further middle to late Iron Age activity was also recorded to the north at Dairy Crest and Cambridge Road, Fenstanton (Ingham 2022; Fig. 3.3). The middle Iron Age phase of Fenstanton Gravels 2 was centred on a single enclosure and a field system that partly overlay the early Iron Age features, suggesting a degree of continuity between the two phases (Fig. 3.18). Within the enclosure were the remains of two roundhouses, suggesting a small domestic compound. To the west of Fenstanton Gravels 2 new settlements were established at Fenstanton Gravels 4 and 3, during the 4th century BC. Fenstanton Gravels 2, unlike these 'later' settlements, did not persist into the late Iron Age, likely ending around the 3rd or 2nd century BC, suggesting that the focus of settlement shifted to the west, to Fenstanton Gravels 4, where at least two phases of middle Iron Age settlement were recorded (Fig. 3.18). Both settlement areas, spaced 200m apart, comprised unenclosed features, with the south-western being the most extensive. Associated with the settlement was a single roundhouse, which contained large quantities of pottery and evidence of structured deposition (see 'Placed deposits'). The dating of this deposit, as with most of the Fenstanton Gravels features, is biased towards pottery, predominantly comprising examples of Scored Ware. The radiocarbon dating of inhumation burial 28.432 returned a date of 390-200 cal BC (SUERC-85552), while one of the two unurned cremation burials in Cemetery 5, located at the north of the site, was dated to 350-50 cal BC (SUERC-85558; Table 3.2). It is possible that this burial dates to the later Iron Age phases of the site, as this period saw a general uptake in cremation burials across the region (see 'Burial patterns'). This pattern of dispersed settlement persisted into the second phase of activity, which saw the setting out of two C-shaped enclosure ditches and a field system, bounded at its western edge by a palaeochannel, which was probably open into the Roman period.

Fenstanton Gravels 3, located just to the west of the channel, comprised further dispersed settlement features, although the overall character of the settlement is unclear as it was largely unexcavated. Geophysical survey to the north showed extensive settlement remains, although the date of these is uncertain, while cropmark data showed an extensive system of rectilinear enclosures broadly aligned onto the palaeochannel, extending to the north-east (Cox 2014; Jones and Panes 2014). Given the high quantity of Roman remains the possibility of these being Roman cannot be ruled out (see Chapter 4).

The enclosures at Fenstanton Gravels 1, 1.5km to the east of Fenstanton Gravels 4, comprised at least two phases of settlement, both of which were located just to the north of a curving palaeochannel (Fig. 3.18). The first phase comprised a rectilinear field system and a single roundhouse. In its second phase, this field system was replaced with a small compound, comprising a rectilinear enclosure divided into two, with a single roundhouse in each cell. Again, as seen at other sites, this suggests changes in the nature of settlement and activity within this area, which could reflect wider changes in patterns of pastoral and agricultural farming (as discussed in the following section). The enclosure was further extended during the middle Iron Age with the addition of a second enclosure, associated with two roundhouses. The roundhouses to the west of this second enclosure appear to have remained in use, suggesting this 'extension' could reflect the presence of a growing population. The hand-built ceramic assemblage comprised wares again indicative of a middle Iron Age date (Banks and Perrin 2024). The ceramic assemblage from Fenstanton Gravels 1 contained no wheel-made wares, with comparative analysis suggesting it may not have continued beyond the end of the 1st century BC. Settlement at this time may have become focused around Fenstanton Gravels 3 and 4. To the north and east are several cropmarks suggestive of further field systems or enclosures, and within the eastern cluster of cropmarks were a number of small enclosures and trackways. It is unclear if these are contemporary with the Iron Age phases of Conington 3, located just to the east of Fenstanton Gravels 1 (Fig. 3.19). Several of the recorded cropmarks align with the later Roman roadside settlement, which at its peak may have extended across much of the area to the north of Conington and Fenstanton Gravels (see Chapter 4).

Contrasting with Fenstanton Gravels 2, the middle Iron Age phases of Conington 3 did not closely correspond with the earlier Iron Age settlement, suggesting either a degree of discontinuity or a replanning of the settlement (Fig. 3.19). The middle Iron Age settlement took the form of a linear boundary and a sequence of conjoined enclosures on a roughly north-east to south-west alignment, corresponding with several of the previously identified cropmarks. Enclosure 11 was formed of two rectangular sub-enclosures with a possible north-facing timber entranceway identified to the western sub-enclosure. Immediately adjacent, a series of curvilinear ditches defined Enclosure 12. The finds and pottery distributions suggest that Enclosure 12 may have formed the focus of activity, with a comparatively high density of pottery, metalworking debris and possible midden material recovered. The ceramic assemblage from Conington 3 included wares indicative of the middle Iron Age (c. 350-100 BC) with the single radiocarbon date from Well 33.140 returning a date of 400-230 cal BC (SUERC-92742; Table 3.2).

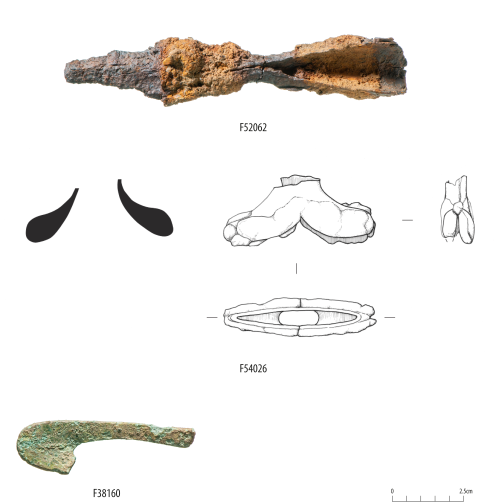

At the south-western extent of the scheme, four middle Iron Age settlements were recorded at Bar Hill, with activity spanning the 4th century BC to 1st century AD. While no direct evidence for late Bronze Age to early Iron Age activity was recorded, two loom-weight fragments were believed to be of this date (F38420 and F38730) . Late Bronze Age to early Iron Age activity was documented at Striplands Farm just to the east, with further activity to the north at Northstowe (Patten and Evans 2005; Evans et al. 2011; Aldred and Collins forthcoming; Fig. 3.3). The settlements at Bar Hill 1 and 4 represent relatively small-scale activity, with the latter probably being closely associated with the large complex enclosure system at Bar Hill 5. This system, centred on the double-ditched Enclosure 11, was probably established in the 2nd century BC and was associated with a second enclosure, Enclosure 14, which may have been used for corralling livestock (Fig. 3.20). These enclosures appeared to have succeeded an earlier phase of unenclosed settlement, echoing the pattern of development at Bar Hill 3, where a large sub-oval enclosure was established in the 2nd century BC, truncating an earlier enclosure and several unenclosed roundhouses (see Fig. 3.32). The shift towards enclosure at Bar Hill 3 and 5 likely reflects an increased emphasis on the definition of space and spatial organisation within settlements, a point that is further considered in the second half of this chapter.

The emergence of middle Iron Age settlements at Bar Hill forms part of a wider expansion of settlement across this area, with multiple Iron Age settlements recorded at Longstanton and Northstowe (Fig. 3.3). At the latter, middle Iron Age activity was recorded in three locations with around 27 individual settlements recorded over an area of 750 hectares, echoing the relatively dense occupation noted at Brampton West. While the precise date at which the Northstowe area was 'colonised' is unclear it was most likely broadly contemporary with that at Bar Hill, which ostensibly forms part of the same densely populated landscape. The middle Iron Age settlements at Northstowe, like those at the A14, comprised a diverse range of types, with an early phase of unenclosed activity that developed into a series of enclosed settlements (Aldred and Collins forthcoming). As at Brampton West, the relative density of settlement within this area suggests the emergence of independent but interconnected settlements, creating wider opportunities and tensions. These themes will be further examined in the final part of this chapter.

Taken as a whole the character of settlement during the middle Iron Age reflects one of rapid expansion, with new areas of settlement being established. The tempo and duration of these is uncertain, but in at least two cases they overlapped with early Iron Age settlements. Nevertheless, the absence of obvious early Iron Age precursors to most middle Iron Age settlements should not be taken as evidence that these were 'empty' spaces. As highlighted in the preceding chapter, the valleys and ridgeways of the Ouse were landscapes of movement or 'landscape communication corridors' (Evans et al. 2015). The presence of scatters of early Iron Age pottery and other finds across the A14 is suggestive of low visibility activity, perhaps connected to seasonal movements, across the corridor. This forms a notable point of continuity with the Neolithic and Bronze Age, whose scattered monuments dot the valley (see Chapter 2). This activity could represent a long drawn out 'pioneering' phase in which populations were actively engaged with the landscapes across the valley. The chief change in the middle Iron Age lies in the increased visibility of the period, created by the establishment of suites of enclosures, trackways and boundaries. These boundaries could be fairly extensive and may reflect the increased definition of territories during the period (Lambrick and Robinson 2009, 80-8). At Brampton South 2, the Iron Age boundary appeared to respect the earlier late Bronze Age-early Iron Age pit alignment, suggesting potential continuity of boundaries over time (see Chapter 2 for discussion of pit alignments). In many cases the settlements recorded across the A14 saw multiple phases of expansion/contraction and changes in function. This shift towards 'permanence' was to continue into the later Iron Age, which saw several settlements seemingly decline while others reached their zenith in the late 2nd to 1st century BC. It is to these changes that the next section will turn, sketching out the key developments and nature of the later Iron Age settlements.

The development of settlements into the late Iron Age presents a complex pattern of abandonment, reduction and expansion. A total of 13 settlements established and developed in the middle Iron Age were 'abandoned' by c. 50 BC. As will be further outlined, this apparent pattern of decline masks a series of complex processes, which saw activity focused within particular landscape locales (Fig. 3.21). These include a particular focus around Brampton West, which saw notable expansion and development in this period. This may have extended to Alconbury, although it is also possible that this settlement was more aligned with further Iron Age activity to the north, including a dense cluster of geophysical anomalies to the north of Alconbury 1 and 2. Owing to this ambiguity, Alconbury is considered as its own 'unit'. Within the central section there is a clear coalescing of settlement around the Fenstanton Gravels and Conington Landscape Blocks, extending north to the Dairy Crest and Cambridge Road sites at Fenstanton, as well as incorporating a dense array of cropmarks. To the east a third foci developed around Bar Hill, which extended further to the north with the nascent settlements at Northstowe and Longstanton. The character and development of each of these blocks is further considered in the next section.

Before examining the expansion and development of the late Iron Age settlements at Brampton West, it is worth considering the development and position of its neighbour at Alconbury, located c. 1km to the north. Only a limited number of late Iron Age features were documented at Alconbury 2, comprising a series of recuts to parts of the enclosures, likely reflecting continued efforts at water management before its abandonment. While no direct evidence for late Iron Age occupation was noted, there was, as attested by the geophysical survey, evidence for dense settlement to the north of Alconbury 2 (in the area of Alconbury 4; see Chapter 4), while the recovery of later Iron Age pottery, including Aylesford-Swarling types, at Weybridge Farm (MCB1048) just to the east of Alconbury 2, hints at further settlement. The degree to which this settlement was aligned to the south with Brampton West is unclear, and it is possible that the Ellington Brook marked the boundary between the two zones; in the absence of additional data it is difficult to comment further.

In contrast to the limited evidence from Alconbury, Brampton West saw extensive development in the later Iron Age. The proliferation of settlement across Brampton West represents the development of individual settlements established in the middle Iron Age but also an increased sense of connectivity with numerous trackways and linear boundaries crossing the area (Fig. 3.21). Activity becomes centred around Brampton West 1, 2, 100 and 102 with Brampton West 202 having fallen out of use, along with the settlements at Brampton South. Activity at Brampton West 1 in the 1st century BC saw the expansion and development of the middle Iron Age enclosure system, with the addition of further enclosures, linear boundaries and field systems extending over c. 0.12km (Fig. 3.22). The radiocarbon dates, finds and ceramic assemblage obtained from later features indicate activity extending into the 1st century AD with the enclosures falling out of use at the very end of the Iron Age. Both enclosures were truncated by two ditches extending from the palaeochannel and probably reflect continued efforts at water management. Radiocarbon dating of a sample from Ditch 7BC.44 returned a date of 100 cal BC-cal AD 70 (SUERC-91482; Table 3.2) indicating it may have been a final (or very early Roman) attempt to make use of the area. Contemporary with this continued settlement, a new settlement was established at Brampton West 2, located immediately to the west of Brampton West 1. Brampton West 2 comprised a domestic focus of activity within an area defined by two parallel boundaries and small plots (Fig. 3.22). The pottery assemblage, like that at Brampton West 1, was dominated by Aylesford-Swarling wares with a minor inclusion of Roman wares potentially extending activity to c. AD 40-60/70 (see Chapter 4). To the south, Brampton West 100 also expanded in the late Iron Age, with the establishment of a series of enclosures, small post-built structures, and ditches (Fig. 3.21). Again, the pottery assemblage comprised Aylesford-Swarling wares, supplemented by limited quantities of hand-built East Midlands Scored Ware and East Anglian Plainware, with the inclusion of early Roman pottery indicating activity persisted into the later 1st century AD, when the site was again extensively redeveloped (see Chapter 4). The activity at both Brampton West 1 and 2 was probably also contemporary with the redevelopment and expansion of the Iron Age settlement at Thrapston Road, Brampton (Reid and Atkins 2019). Here the earlier Iron Age activity was superseded by an enclosed settlement to the east. During the later Iron Age a series of substantial sub-square and sub-rectangular enclosures were created, echoing the patterns of development noted at Brampton West.

The most extensive redveloped transformation was at Brampton West where a series of enclosures, trackways, and linear boundaries were established, representing an intensification of activity and a formalisation of the settlement (Fig. 3.23). The settlement continued to maintain the north-west to south-east alignment established in the middle Iron Age, suggesting a degree of fossilisation in land rights and/or boundaries. The activity was concentrated in two areas connected by a series of trackways, with a small cremation cemetery (Cemetery 102) and three pottery kilns located to the south-east (Fig. 3.23). These form part of a wider group of early kilns recorded across Cambridgeshire, reflecting changes in pottery technology alongside the introduction of new pottery forms (see Sutton et al. 2024). The majority of this activity was located close to the connecting spine ditch, which probably served to define the limits of settlement as well as the wider agricultural hinterlands associated with the settlement. At the northern end was a pair of enclosures, which were connected to a series of trackways. These underwent numerous modifications over time, potentially reflecting wider changes in the location of the associated fields. Both enclosure ditches contained quantities of Aylesford-Swarling wares, which comprised the bulk of the late Iron Age ceramic assemblage from Brampton West 102. When considered alongside the radiocarbon dates and other finds it indicates that the late Iron Age phase of Brampton West 102 probably spanned the 1st century BC to 1st century AD, representing an intensive phase of activity.

To the south-east, the impression of West of Ouse as a transitional landscape to this more concentrated activity continues, with late Iron Age activity confined to dispersed pits across the eastern areas of the Landscape Block (TEA15 and 16; Fig. 3.24). The ceramic assemblage from West of Ouse 2 was distinct from that of the earlier activity, being dominated by wheel-made wares dated to the first centuries BC and AD (Sutton and Hudak 2024a). On the eastern side of the river, at River Great Ouse 2, only a limited number of features could be directly dated to the late Iron Age including a stone trackway, ditches, pits, post-holes and a waterhole, though it is likely that many middle Iron Age features remained in use (Fig. 3.24). The rare cobbled routeway has few parallels but an example at Brigstock, Northamptonshire, was interpreted to date from the 2nd to 1st century BC (Jackson 1983). A metalled surface was also noted at Bar Hill 3, forming part of the enclosure entrance and could represent efforts at ground consolidation in light of increasingly waterlogged conditions. Possibly both West of Ouse and River Great Ouse were occupied seasonally, forming part of the wider hinterland of Brampton West, with the River Great Ouse and its floodplain defining the eastern limit of this settlement agglomeration. The use of rivers as territorial boundaries is widely noted with several sites within the Thames Valley showing signs of modification or incorporation into settlement boundaries (Lambrick and Robinson 2009, 62). In the A14 landscape, this association appears to extend to the deliberate positioning of settlements close to water. The partitioning of space also emerges as a key theme at Brampton West during the later Iron Age, with its northernmost settlement nestled within the bend of a palaeochannel and its central area defined by a sequence of linear boundaries and trackways. This highly organised landscape contrasts with the more dispersed nature of the later Iron Age settlement within the central section of the A14 at Fenstanton Gravels and Conington.

By the late Iron Age, Fenstanton Gravels 2 appears to have fallen out of use. Instead Fenstanton Gravels 4 appeared to form the primary focus of occupation during the period, with at least three areas of occupation recorded towards the southern edge of the settlement. These were associated with a series of enclosures, field systems, as well as a south-east to north-west aligned trackway. (Fig. 3.25). Just to the east of the north-western end of the trackway was a single banjo enclosure, which could have been used for the corralling of livestock. Fenstanton Gravels 4 displayed evidence for expansion and development into and throughout the Roman period (see Chapter 4), providing evidence for the continued importance of specific locations. Further Iron Age features were recorded at Fenstanton Gravels 3 to the north-west, comprising a limited number of ditches and enclosures, while at Fenstanton Gravels 1 elements of the middle Iron Age enclosure system remained in use, being partially redefined through the addition of several further ditches. Of particular note is the increase in the number of roundhouses associated with the enclosures, although it is unclear if these are contemporary with each other or reflect multiple episodes of occupation.

At Conington 3, the settlement appears to have persisted into the late Iron Age in a much-reduced form. The middle Iron Age enclosures appear to have been abandoned before the second half of the 1st century BC, with the focus of activity shifting to the north-east. Within this area the remains included a series of small ditches and gullies forming part of a field system, a small post-built structure, a group of pits, and the southern terminus of a large boundary ditch. Occupation seems to have ceased by approximately 50 BC.

Unlike the settlement features excavated at Brampton West, those at Fenstanton Gravels and Conington are seemingly marked by a lack of physical interconnectivity, comprising a range of features dispersed across the landscape. This could reflect the limitations of the excavation, and it is possible that further elements of Fenstanton Gravels 4 lie to the south of the limit of excavation, while as noted in the case of Conington the existence of a suite of cropmarks extending north of the A14 is indicative of further settlement. The form of at least one area of the cropmarks in plan is suggestive of Iron Age enclosures similar to Brampton West (Fig. 3.23). In addition, further Iron Age remains were recorded at Dairy Crest and Cambridge Road, Fenstanton, although the precise phasing of these is at present uncertain (Ingham 2022). The development of settlement within this area finds parallel within the Bar Hill block, where distinct settlement foci were identified, not only within Bar Hill itself, but also just to the north at Northstowe.

During the early 1st century BC there are marked changes in the size and layout of the enclosures at Bar Hill 3 and 5, suggestive of increased spatial division within the settlements. The large sub-oval enclosure at Bar Hill 3 saw a reduction in the size of the enclosed space, though with the addition of an annexe defining a small area for the penning of livestock (see Fig. 3.32). The reduced interior space appears to have formed the focus for domestic occupation, with the space being further divided by a series of smaller enclosures in the southern half. While appearing to suggest a decline or contraction in the scale of activity, it is probable that this reflects changes in the way that space was organised and managed, with a clearer split between occupation and non-occupation areas being established.

This process is also noted at Bar Hill 5 during the 1st century BC, although here the definition of space appears to be less clear (Fig. 3.26). The earlier large double-ditched enclosure (Enclosure 11) appears to have largely fallen out of use, although it seems to have been partially recut across its northern edge. The 'final' use of the enclosure is marked by the placement of an infant burial (381956) dated to 160 cal BC-cal AD 30 (Beta-63492; Table 3.2). Associated with the infant remains were a perforated dog tooth amulet (F38189) , while two late Iron Age coins (F38190 and F38192) from the same context, although not directly associated with the burial, could represent further grave goods (Scholma-Mason 2024). The coins comprised a 'Bury Diadem' and a 'Broadoak Boars' type, from Essex, both of which are traditionally dated to the late 1st century BC, although close dating of Iron Age coins is often problematic, drawing largely on known historical events (Haselgrove 2019, 243; see discussions in Bowsher 2024f; Marshall and Humphreys 2024). The remainder of the settlement is characterised by a complex sequence of intercutting enclosure ditches, with activity generally being centred around Enclosures 9 and 15. As at the other A14 sites an assemblage of Aylesford-Swarling wares was recovered along with several 1st century BC brooches. Among the latter were examples of Nauheim and Drahtfibel types (Marshall and Humphreys 2024). While the precise chronology of this enclosure sequence is uncertain, it does suggest sustained, albeit potentially reduced, activity throughout the 1st century BC, overlapping with activity at Northstowe. Unlike Bar Hill 3, which had largely been abandoned by the Roman period, Bar Hill 5 saw extensive redevelopment, with the setting out of a new system of enclosures (see Chapter 4). The layout of both settlements appears to reflect a concern with the management of livestock, a point reinforced through analysis of the faunal data from the sites.

The contemporary settlements at Northstowe, just to the north of Bar Hill 5, also underwent changes during this period, with - as at Brampton West - several of the earlier sites undergoing processes of consolidation and expansion. Within this scheme the settlement at Bar Hill 5 could have formed part of the wider agricultural hinterland of the Northstowe 'centres', echoing the consolidation of activity to the west at Brampton West.

The apparent decline in settlement abandonment and aggregation of settlements in the late Iron Age was influenced by a multitude of social and environmental factors. The final phases of Alconbury 1 and 2 were characterised by the replacement of the enclosures with a small field system, suggesting domestic occupation had shifted elsewhere. In the case of Brampton West 1 and Alconbury, the abandonment of the sites at the beginning of the late Iron Age appears to have been prompted by increasingly waterlogged conditions. This process, while having its origins in the late Bronze Age, persisted into the late Iron Age and may have led to the abandonment of many low-lying sites in favour of new settlements on higher ground (Abrams and Ingham 2008, 29).

This apparent decline in settlement was not universal across the A14, with several sites showing signs of expansion or aggregation, incorporating aspects of enclosed, linear and open settlements. The pattern at Brampton West perfectly demonstrates the difficulties in ascertaining changing settlement patterns. The excavations at Brampton South and Alconbury are moderate in scale and if considered in isolation may be interpreted as indicating decline. However, when considered alongside the evidence from Brampton West, the picture that emerges is one of settlement aggregation, with settlement being focused within a number of key areas. This process can be seen across the A14, including the aggregation of settlement around Bar Hill and Northstowe. Alongside this there is increased evidence for interconnectivity and zoning of activities. This includes the increasing use of enclosures to define areas of settlements, and within these further subdivisions, marking out zones of activities. The process of enclosure could reflect settlement status as well as facilitating water management, as the environmental evidence suggests many of the ditches contained standing water, which could have been utilised as water sources for livestock, offsetting the need for wells or waterholes within the enclosures, at least at certain times of the year. The specific function and utilisation of these spaces is more fully considered in the following section.

The Iron Age of the A14 is characterised by a strikingly diverse range of settlement forms developing from the middle to late Iron Age against a backdrop of changing environmental conditions, social structures, agrarian economies and material culture. What emerges from the framework outlined above is the apparent concentration of settlement features within particular landscape locations. The majority of the Iron Age settlements across the A14 are often located within areas that afforded access to a diverse range of resources, extending from rich pasture to a range of dryland and wetland resources, the latter of which would have been subject to seasonal flooding. The proliferation of boundaries and enclosures during this period, potentially reflecting changes in agricultural practices, tenure, community and connectivity, results in the greater visibility of middle-late Iron Age settlement across a range of landscape settings.

To examine these points further, aspects of settlement organisation and economy will now be explored, starting with an exploration of the middle Iron Age settlements at Alconbury, before turning to the three main foci of settlement that developed in the middle Iron Age and persisted into the later Iron Age. This review examines these aspects across the middle to late Iron Age, eschewing the earlier split into middle and late in order to develop a longer-term perspective of changing settlement function.

To the north of the Ellington Brook, the organisation and development of the settlements is closely tied to the local landscape and environment. The settlements at Alconbury were connected through a curving linear boundary, with activity at Alconbury 1 probably defining the earliest part of the middle Iron Age settlement, and Alconbury 2 reflecting a slightly later expansion or development. The development of Alconbury 2 saw an increased focus on enclosure but appeared to retain the alignment of the earlier linear boundaries, which served to define a broadly U-shaped 'internal' area (Fig. 3.27). As previously outlined, our understanding of this area is reliant on the cropmark data which suggest the presence of internal divisions and trackways. The space between Alconbury 1 and 2, measuring at least 14ha, may represent a space used for overwintering cattle, but could, like the annexe at Bar Hill 3, have been used for a range of seasonal activities. The partitioning of the inner space into two would have allowed for the separation and sorting of livestock, with further divisions being created using movable hurdles or screens.

The area to the south-east beyond the boundary could represent summer pasture and, as suggested by the environmental evidence, perhaps also as managed floodplain hay meadows (Wallace and Ewens 2024; Fig. 3.27). During the spring the vegetation across this area would be allowed to grow before being cut in midsummer as a hay crop. In summer, the cut area would be used as grazing for animals, preventing taller coarser species from becoming dominant. This system created food for cattle not only during the summer but also in winter, when the high-nutrient hay could have been employed as fodder. This need for fodder may have been influenced by a focus on dairy cattle, as indicated by the culling of very young animals and the presence of older animals. Alongside this there was also evidence for a focus on meat products (Cussans 2024; Wallace and Ewens 2024). The area beyond the western edge of the settlement could have been used as arable land or formed part of the wider pastoral landscape, potentially being used for grazing cattle prior to their summer transfer to the floodplain meadows, or for keeping sheep, which generally have wider grazing patterns. The boundary could have fulfilled a range of roles, including protecting crops from grazing livestock, as well as an aid to funnelling animals into the interior of the enclosure, which could have been further helped by the use of dogs, of which there was at least one example at Alconbury 2 (Cussans 2024).

Turning from the 'empty spaces' to the function of the enclosures at Alconbury 2, there is an apparent focus of activity within Enclosure 3 with an antler comb associated with textile working, which could have been the primary drive for rearing sheep on site (Wallace and Ewens 2024). While kiln furniture was recovered from a series of large pits within the enclosure it is unclear if these are intrusive from the Roman reuse of the site (Machin 2024a). There was limited evidence for cereal cultivation or processing; this may have taken place at low intensity within small garden plots or to the west within the open fields, with the focus of the site appearing to be animal husbandry. The presence of scarabaeoid dung beetles in the Enclosure 3 ditch and in Waterhole 5.70 with Enclosure 2 suggest that some livestock may also have been kept within these areas (Allison 2024a). The analysis of Iron Age wetland settlements, such as at Black Loch of Myrton (south-west Scotland), Flag Fen and Glastonbury Lake Village, point towards temporary stalling of animals and periods of animal-human cohabitation (Mackay et al. 2020). The more spatially constrained enclosures at Alconbury, which appear to include areas of domestic occupation, may have allowed livestock to be kept in close proximity for rearing, breeding and care.

The final phase of Alconbury 2 indicates a dramatic shift in activity with the development of Field System 2, which formed land parcels attached to a late phase of occupation. By this point the settlement may have been more open, reflecting changing agricultural practice and settlement organisation, with no evidence for domestic activity into the late Iron Age. The patterns observed at Alconbury provide a template through which we can explore the wider landscape, highlighting the potential zoning of activities and the importance of natural features such as palaeochannels for settlement arrangement. The proposed arrangement of activities at Alconbury risks being branded as 'environmentally deterministic' but the organisation of settlements was intrinsically linked to a variety of factors both social and environmental.

The middle to late Iron Age phases of settlement at Brampton West represent one of the densest concentrations of features within the A14 corridor. The contemporary activity at Thrapston Road, Brampton, to the north-east could represent further elements of wider settlement landscape associated with Brampton West. As highlighted previously, two distinct phases can be defined, with the settlement initially developing during the middle Iron Age and reaching its apogee in the late Iron Age. The growth and development of settlement across the landscapes is stimulated by a range of factors, including an apparent expansion in agriculture as evidenced by the increase in the range of enclosures and trackways associated with all the settlements. Importantly, as at Northstowe and Bar Hill, these settlements are closely interrelated, independent yet interconnected. The nature of these connections can be observed through a consideration of the development of the settlements over time and the changing functions being undertaken. Owing to the scale of the data from Brampton West, as well as its importance for illustrating a number of key themes of the period, this section firstly considers aspects of agriculture and settlement function, exploring the relationship between features and arable/pastoral strategies on site. The second part considers the nature of domestic occupation and of several smaller scale 'industries' at Brampton West.

From the outset the middle Iron Age settlements of Brampton West had a clear focus on spatial divisions, employing a mixture of natural boundaries (rivers/streams) alongside created boundaries, as indicated by the presence of hedgerow taxa, which could have served to further divide fields or define enclosures. During the middle Iron Age, the settlement at Brampton West 1 could have functioned in a similar fashion to that at Alconbury 1 and 2, with its position next to the palaeochannel facilitating access to floodplain meadows as well as rich grazing areas, owing to the presence of free draining soils (Fig. 3.28). The waterlogged plant remains from the site indicated the presence of a high water-table, with grass and scrubland in the surrounding area (González Carretero 2024). This impression is further reinforced by the presence of several species of freshwater snails recovered from across the Landscape Block (Pipe 2024c).

As at Alconbury 2, it is probable that livestock at Brampton West 1 were moved across this landscape throughout the year, with a series of trackways appearing to extend to the palaeochannel, facilitating the movement of livestock to these meadows, while during the other months of the year livestock were moved into wider areas of pasture. The faunal data indicates that livestock during this period principally comprised caprines, with other domesticates being comparatively scarce. Sheep were kept with a focus on meat, although it is also possible that a range of secondary products were also exploited. The apparent absence of lambs suggests that these were kept elsewhere. Cattle were present but in relatively small numbers. Given the general preference of sheep for drier and wider areas of pasture it is possible the cattle were kept within the floodplain meadow, with sheep being kept in the larger areas of pasture to the south. Isotopic analysis of sheep bone suggests that these tended to graze across wider areas with more canopy cover or closer to the freshwater peat-fens than the cattle (Moore et al. 2022; Wallace and Ewens 2024).

The area to the south of Brampton West 1 was largely devoid of features, except for those associated with Brampton West 100 at the eastern end of the TEA (Fig. 3.29). As at Alconbury 2, these 'empty spaces' could represent key elements of the agricultural landscape, defining potential areas of arable cultivation or grazing, which may have been shared by the settlements at Brampton 1 and Brampton 102. While the middle Iron Age phases of Brampton West 102 are partly obscured by the extensive development of the site in the late Iron Age, there is a clear sense of a complex and divided landscape, with two cores of activity at the northern and southern end of the Landscape Block, with open areas of field and pasture between them. Curiously, these sites appear to exist on the same alignment as those at Brampton South, suggesting a potential persistence of earlier prehistoric routeways or alignments. Alternatively, the axis of these sites could have been influenced by local topography, with the sites generally occupying an area of ground at the base of a slight ridge (Fig. 3.29). This positioning also appeared to reflect the boundary between an area of free-draining soil and heavy lime-rich soil. As at Alconbury 2, it is likely this placement was informed by an awareness of local ground conditions. The positioning of the site within this area would have facilitated access not only to rich grazing land in drier upland areas but also fertile soils, which extended to the south. These patterns of movement appear to be partly reinforced through the orientation of the middle Iron Age trackways that cross this 'boundary', reinforcing the impression that livestock were being moved between different areas of pasture. This hypothesis could be extended to suggest that the previously discussed open spaces at the settlements were, like the interior of the space at Alconbury, used to overwinter cattle. Isotopic analysis of cattle remains from Brampton West does suggest potential seasonal shifts between grazing and foddering (Moore et al. 2022; Wallace and Ewens 2024). In this regard, access to and the management of floodplain meadows emerges as a key aspect of the agricultural regime, underscoring the importance of these resources at both Alconbury 2 and Brampton West 2. During the winter this pressure on food resources may have been offset through modest culling, a practice that is evidenced in the faunal assemblages across the A14 (Wallace and Ewens 2024). The use of extensive grazing areas would also have helped to alleviate these issues (Lambrick 1992), and this could account for the large number of 'empty spaces' at Brampton West, reflecting an extensive system of grazing and arable land.

The faunal remains from Brampton West 102 suggest a focus on cattle husbandry, contrasting with the sheep-dominated assemblage at Brampton West 1. While settlements likely practiced a range of economic activities, the patterns observed at Brampton West may indicate an emphasis on particular activities at specific locations. This could include the potential movement of cattle from Brampton West 1 to other areas for butchering. The limited butchery evidence at Brampton West 102 suggests a focus on marrow extraction. Marrow could have been extracted for consumption, representing a high nutrition resource. In at least one case a fragment of cattle bone had been sawn to form a flat spacer or inlay. Alongside a focus on meat there was evidence for cattle breeding on site and dairying. The evidence for dairying is further illustrated through isotopic analysis, which suggested that the Iron Age cattle birth season was spread over a prolonged period of 9 months, indicative of a dairying economy (Moore et al. 2022; Wallace and Ewens 2024).