Cite this as: Major, H. 2015, An overview of the small finds assemblage, in M. Atkinson and S.J. Preston Heybridge: A Late Iron Age and Roman Settlement, Excavations at Elms Farm 1993-5, Internet Archaeology 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.1.major6

Follow the links provided for more details for each category.

This section on the small finds assemblage sets out to gives an overview of the composition, size and nature of the small finds assemblage as a whole, as well as making some judgements on the importance/value of the assemblage and how it contributes toward the interpretation of the settlement.

The small finds assemblages have been grouped by perceived function category (Crummy 1983), rather than material and type. Thus items of personal adornment and dress such as brooches, hair-pins and beads are treated as a group (Finds Function [FF]1). The intention of this method is to facilitate an improved appreciation of the significance of their group value and to enhance their contribution to the interpretation of the site of what is otherwise a very large and diverse collection of artefacts. However some types of finds have more than one function and this is acknowledged with the separate reporting of such items as grave goods, where the individual elements (pottery, brooches) could equally be represented within the overall pottery report or personal adornment finds function group. Equally it has not been possible to ascribe a purpose to some items and these have been grouped together as items of unknown use.

The complete list of finds may also be downloaded from the digital archive.

Items of personal adornment formed one of the largest groups of finds from the settlement. Most are Roman, but the brooches in particular include a good range of pre-conquest forms.

A very large number of brooches were found on the site. Excluding the brooches from the cremations and pyre features, 248 Late Iron Age and Roman brooches were recovered from the settlement. The majority are pre-conquest and Early Roman types, as would be expected in the south-east, but there is also a good representative sample of 2nd-century and later forms present. It appears unlikely that pre-conquest Heybridge was a major entrepôt for continental brooches, as if that had been the case it would be expected to show a greater incidence of continental forms than on inland sites. However, the wide range of forms present shows that before AD 43 the Elms Farm population had access to as wide a range of continental forms as the tribal centre at Camulodunum.

Brooch use drops from about AD 70, but there is still a steady trickle of brooch loss through to the end of the Roman period. Knee- and P-shaped brooches occur in particularly good numbers. The latter group and many of the former are continental-made, and one reason for their presence may simply be that the settlement had direct access to continental markets, rather than relying on trade through London or Colchester. However, Knee-, P-shaped and Crossbow brooches are all types associated with the military, and perhaps the civilian administration, and it may be that they are indicative of an 'official' presence of some form at Elms Farm during the later life of the settlement. There is also a fair amount of Late Roman military metalwork from the settlement, although some of this, at least, may have been brought to the site for recycling.

There is a small amount of evidence for brooch manufacture at the settlement, consisting of a possible unfinished plate brooch, and a fragment of another brooch of possible local manufacture, both from Late Iron or very Early Roman contexts. There are no brooch moulds from Elms Farm, though there are a number of moulds for other objects.

Hairpins were fairly abundant on the site, with examples made from copper alloy, bone, glass and jet. Hairstyles requiring the use of hairpins were a Roman fashion, and evidently one that quickly became popular in southern Britain after the Roman conquest.

The bone hairpins fit happily into the Colchester type series (Crummy 1983, 19-27), with one exception. The head of this pin was incomplete, but was probably either lyrate or in the form of a caduceus, both symbols of Mercury. There is no evidence for the bone hairpins having been made at Elms Farm, and they are possibly Colchester products. The forms present were mostly mid-Late Roman, with the early types poorly represented, and found only in contexts where they must have been residual. Only one bone hairpin fragment actually came from an Early Roman context.

Overall, there were more hairpins made from copper alloy than bone (thirty-two as opposed to thirty-one), including the bone shaft fragments, some of which may have been from needles. This high proportion of copper-alloy hairpins appears to be unusual, and might merely be the result of poor preservation of bone (bone objects in general were sparse); however, the assemblage of unworked bone is large, and worked bone generally survives in better condition than unworked bone. In a sample of fifty-three published sites with more than ten hairpins, only eight (15%) had more copper-alloy hairpins than bone hairpins (the sample being fairly random, and based on a pre-existing database). Of these eight, half were temple sites, as opposed to only 13% of the sites with more bone than copper-alloy hairpins. The discussion of votive assemblages in the Uley report (Woodward and Leach 1993, 332) highlights those temples where the large quantities of hairpins found suggests that they had votive significance, which cannot be argued for the relatively modest collection from Elms Farm. There were, for example, 320 hairpins from Lydney. However, the evidence also seems to suggest a connection (though not an exclusive nor invariable one) between temples and a high proportion of copper-alloy hairpins, regardless of whether the overall total is particularly high. Moreover, three out of the four temple sites with more copper-alloy than bone hairpins were in Essex (the fourth was Henley Wood, Somerset), whereas none of the other temple sites were from the county (it is noted that the three non-temple sites from Essex in the sample had more bone hairpins than copper alloy). It is therefore possible that the Elms Farm hair-pins represent a regional variation in depositional practice.

It is difficult in practice to investigate this hypothesis further at Elms Farm. While there were equal numbers of hairpins in each material found in the temple precinct, they span the entire Roman period. In fact, looking at the site as a whole, Period 3 is the only phase in which copper-alloy hairpins outnumber bone ones (nine copper alloy to four bone). Since, as discussed below, there is little evidence for deliberate deposition of any class of find in this period, the preponderance of copper-alloy hairpins may not be related to preferential votive deposition. Crummy (1983, 20) suggested that bone hairpins might be locally made, low-cost copies of metal pins; if this is the case, then the relative scarcity of bone pins in the Early Roman phase of Elms Farm may reflect the relative wealth of the site. Copper-alloy pins may simply predominate during this period because the inhabitants could afford them.

Glass hairpins normally have globular heads and either a plain shaft with circular section, or a twisted 'barley-sugar' shaft. Both pins from Elms Farm are broken beneath the head, but there is evidence that at least one of them once had a twisted shaft. Glass hairpins are considered to have been in use during the Late Roman period (Cool and Price 1998, 194; Crummy 1983, 28). Hairpins are commonly found near the skull in burials; four glass pins were found in a grave in the Butt Road cemetery (Crummy 1983, 28). The twisted shaft from a hairpin was found in previous excavations at Crescent Road, Heybridge (Drury and Wickenden 1982, 28, fig. 12.23) in a Late Roman/Early Saxon context. The examples from Elms Farm are unstratified.

There was only a single jet hairpin from the site. Jet hairpins are mainly Late Roman, and are far less common than bone or copper-alloy pins. A survey of 112 published sites of various types (undertaken by the author) showed that jet pins occurred on only 18% of the rural settlements in the sample; by contrast, 35% of the urban sites yielded jet hairpins. Elms Farm is thus fairly unusual in having even one jet hairpin.

Only one definite earring was identified, but they are probably under-represented since broken earrings are very difficult to identify, particularly the simpler forms. Fragments which could be parts of earrings include a probable finger-ring cut down from a three-strand cable bracelet, and a small copper-alloy rod fragment with very thin silver wire wrapped round it. Any broken rings of suitable size are also candidates for earrings. In addition, fragments of chain may be parts of earrings rather than necklaces, as may pendants such as SF8158 (no. 499 in the catalogue), or the small clapperless bells included in function category 20.

The majority of the beads found would have formed parts of necklaces, but they were also used in earrings and bracelets, often threaded onto wire. The single semi-circular jet bead would have been from a segmented bracelet. As is usual, glass beads were most common, with a lesser number in jet and shale (Table 57). Apart from one from a 2nd-century layer, all the jet and shale beads were from mid-3rd to 4th-century contexts, reflecting the general popularity of jet jewellery at that time. There is a concentration of glass beads in the temple area, though it should be borne in mind that the distribution of beads as a whole is influenced by the fact that a relatively large proportion of these small objects came from soil samples, and the temple area was extensively sampled.

Other parts of necklaces, such as metal chains and links, are poorly represented, and all may be from other objects - the woven copper-alloy rope fragment, for example, could be from a suspension chain rather than jewellery, although a small S-shaped hook is most likely to be from a necklace.

The number of bracelets from the site was not particularly large (Table 58), comprising thirty-six copper-alloy bracelets, one silver, twenty-five shale, and one bead from a segmented bracelet made from jet. Unlike brooches, for example, bracelets were not commonly worn in the Late Iron Age, and there were none at this site from pre-Roman contexts. Indeed, there are only five from Early Roman contexts, and none from mid-Roman. Of the thirty-two bracelets from closely dated contexts, two-thirds come from Period 5-6. The wearing of bracelets can be regarded as a mainly Late Roman practice at this site.

Many of the later Roman decorated bracelets can be paralleled at Colchester, and for some at least, a common source is likely. Number 400, for example, has closely spaced punched ring-and-dots very similar to those on a bracelet from the Butt Road cemetery (Crummy 1983, 44, no. 1708). In her study of the distribution of Late Roman bracelets, Swift (2000, 136) notes that this motif is more common in Britannia than on the continent, and that it has a south-western bias.

The evidence suggests that there was a votive aspect to the deposition of the later Roman bracelets, though it was probably not a strong tradition at this site. The structured deposition of bracelets is also considered further below (3.7.1.11 Religious Activity).

The site produced a total of thirty-two finger-rings in various materials, three loose intaglios, and three possible ring fragments (Table 59). Most were 'trinket rings' made from copper alloy or iron, but there were also five silver rings, a gold ring, and a very fine silver-gilt bezel appliqué depicting Leda and the Swan (Figure 447).

A range of styles was present, spanning the whole Roman period, though only twelve of the rings were from stratified contexts. One of the intaglios is of interest, as it may provide evidence for the source of some of the jewellery found at Elms Farm (Figure 448). This nicolo intaglio showing a satyr bears an inscription on the back, apparently in Greek, reading EYTY for Eutyches. Henig suggests that it may have derived from a Colchester jeweller's workshop, since the only parallel is from Colchester, and further suggests that the workshop may have employed Greek freedmen. The Colchester nicolo also shows a satyr, and has the name EYCEBI for Eusebius on the back. This is a useful reminder of the cosmopolitan nature of life in the towns of Roman Britain, and also underlines the fact that many of the 'luxury' goods found at Elms Farm would have been made at, or traded through, Colchester.

Evidence for footwear, in common with many other sites, was very limited, depending principally on the survival of leather in waterlogged contexts. Fragments of about seventeen shoes came from four late 2nd to 3rd-century wells at Elms Farm, most from a large timber-lined well in Area H (context 16083). The leather was in poor condition, with little of the shoe uppers surviving.

Where it was possible to determine, the shoes were of thonged and nailed construction. In only one instance was the evidence present for identification of a calceus, a closed shoe, although it is assumed that this style would have predominated. This was the 'best' shoe from the assemblage, with its sole nailed in a leaf-and-tendril pattern paralleled both in Britain and on the continent. Other styles present were a closed, latchet front-fastening boot, and sandals of late 2nd to early 3rd-century types. Only one shoe can certainly be identified as male, and no women's shoes can be positively identified. There is one certain child's shoe.

A total of 788 iron hobnails were recovered (excluding those in situ in shoes), but retrieval of hobnails on site appears to have been patchy, as a large proportion came from soil samples. Unfortunately, they were similar in appearance to the small lumps of iron pan that had formed in many contexts, and that were themselves often mistakenly collected as iron objects. Nevertheless, the assemblage included several groups, of varying date, which must represent discarded footwear rather than individual losses, representing six or seven shoes in all. They came from pits, a disused kiln, and a prepared surface. In addition, there were three iron cleats, which may be from boots.

There were a few other items from the site that may belong in this category, including fragments of several delicate copper-alloy chains, which are probably from jewellery, and a possible copper-alloy wire bracelet with silver thread wound round it. One of the few pieces of Late Iron Age jewellery found (apart from the brooches) was part of a crook-headed pin, an object more likely to be a dress-fastener rather than a hairpin in the Roman style. At the other end of the Roman period, a small number of perforated Roman coins may represent Early Saxon reuse as pendants. Perforated Roman coins are occasionally found in Early Saxon graves, and it is thought that the coins may have been considered to have amuletic properties.

The most common types of toilet instrument - tweezers, nail cleaners and cosmetic instruments of various sorts - are all present at Elms Farm, but there is no great quantity of a single type (Table 60). Most are of middling quality, with the exception of one of the spoon-probes which would have been rather splendid originally, with elaborate moulding, and inlaid silver wire. The five folding knives may belong in this category, if they are considered to be razors, and possibly some of the other small knives. Some of the stone slab fragments may be mixing palettes for cosmetics or medicines, but none have the bevelled edge typical of such palettes.

This is one of the few categories that includes copper-alloy objects from pre-Roman contexts, though critical examination of the dating of the contexts suggests that not all are necessarily pre-Roman. The only items that are definitely from pre-conquest contexts are a probable pair of tweezers, and a probable mirror fragment.

Compared to some types of artefact, nail cleaners are very variable in their shape and decoration. They can occur in pre-conquest contexts (although none on this site are definitely pre-conquest), and continue in use throughout the Roman period. The nail cleaners from a particular site are often more similar to each other than to those from other sites, suggesting localised manufacture, although the five examples from Elms Farm are all of different forms. The number of nail cleaners and tweezers found is lower than might have been expected.

There were parts of seventeen definite or probable pairs of tweezers from the site. All were made from copper alloy, except for a single iron pair. The forms were all simple. Twelve of the pairs of tweezers were from dated contexts, predominantly Periods 2-3. There are no examples from the Northern hinterland (W) and Northern Zones (D, E and F), and the majority came from the Central and Southern Zones.

Definite or probable mirror fragments came from eight contexts, potentially representing the remains of at least nine mirrors. This is a large assemblage in terms of mirrors, although none were complete enough to confidently assign them to any of Lloyd-Morgan's groups (Lloyd-Morgan 1981). The diameter and thinness are, however, consistent with the mirrors of Lloyd-Morgan's Group S - Mirror Boxes (Lloyd-Morgan 1981, 78). These are small 'almost paper thin' silvered bronze mirrors set into small circular boxes.

Four pestles and three fragmentary mortars from cosmetic grinder sets were found during the excavations. Cosmetic grinders appear to have been among the classes of object sometimes dedicated at temples. However, none of those from Elms Farm was found within the temple or its precinct, and the Elms Farm cosmetic sets are perhaps best regarded as part of the general detritus of the settlement. In view of the evidence for metalworking it is quite conceivable that some, if not all, were made at the site. If individually they are of modest appearance, numerically they are of some interest, for none of them belongs together, so they represent seven separate sets. Although their numbers are of a different order to the two hundred and fifty or so brooches found, they nevertheless imply a currency suggesting everyday use of cosmetic sets at this relatively low-status rural settlement.

It is not possible to make any definitive statements regarding the wealth or personal appearance of the inhabitants of the settlement based on the toilet implements. The low numbers of tweezers and nail cleaners might suggest either a lack of money or a lack of inclination for personal grooming, but this is contradicted by the larger than expected number of mirrors and the cosmetic grinder sets; the mirrors in particular were an expensive item.

Many items in the household would have been made from organic materials, and the inventory must therefore be presumed to be very incomplete (Table 61). Pottery vessels and glassware also belong in this category, but are summarised elsewhere in this report.

The most common type of artefact relating to food preparation was the quern, used for grinding grain. Saddle querns have been included in this report, though most, if not all, should probably belong to the prehistoric phase of the site. Evidence from other sites shows that saddle querns were still in use alongside the technologically superior (and less back-breaking) rotary querns during the greater part of the Iron Age, but it is impossible to say whether the single saddle quern fragment from Period 2 at Elms Farm is contemporary or residual. Certainly, there was reuse of fragments as building rubble and sharpening stones.

As a whole, the quern assemblage is one of the largest from Essex, with fragments from over two hundred rotary querns (and one millstone fragment). The county has no naturally occurring stone suitable for the manufacture of rotary querns, so all querns (or blanks for making querns) were of necessity imported. The majority of the querns were made from puddingstone, lava and Millstone Grit, which are the standard types of stone used for querns in Essex. The ubiquity of quernstones on the site is a reflection of the sheer amount of time and effort that was expended over the lifetime of the settlement in simply preparing that most basic of processed foodstuffs, flour.

The earliest rotary querns from the site were bun-shaped, and made from Hertfordshire puddingstone. Prior to this excavation, no puddingstone quern had been recovered from an Iron Age context in Essex, despite the bun-shaped form being essentially pre-Roman. Even outside Essex, there are very few examples from Iron Age contexts, mostly dubious, and it has been hitherto impossible to suggest a date for their introduction. Four of the thirty-one pieces from Elms Farm are from Period 2 contexts (Late Iron Age and Roman transitional), including one from pyre debris pit 15417, and it seems likely from the dating evidence that puddingstone querns were in use on the site by about AD 25 at the latest. The fact that the bulk of the fragments were discarded in Period 3 (up to c. AD 160) suggests that they continued in use into the Early Roman period. Most would only have been discarded when they broke, or became too worn to work efficiently.

The use of imported Rhenish lava querns, initially brought into the country by the Roman army, spread very quickly - they were lighter, easier to use, and produced a finer flour. After the mid-2nd century, the deposition of lava querns dropped off, with a corresponding increase in the deposition of Millstone Grit querns. While some Millstone Grit occurs in earlier Roman contexts, the increase in the use of this stone, which probably produced a coarser and more gritty flour, may not have been one of choice. The civil war in the later 2nd century may have disrupted the supply of lava to Britain, and the trade never seems to have fully recovered.

The Elms Farm assemblage includes ten definite querns, and one dubious example, in non-standard stone. The stone types represented are gneiss (possibly erratic); greensand; pebbly sandstone, possibly the Sherwood Sandstone Group; Purbeck marble; grit (possibly Millstone Grit series); and an unsourced sandstone. The shape of all the pieces is the normal Roman flat quern, apart from one of the sandstone fragments, which has a large hopper with a flat rim, a southern British form rare in Essex, and another sandstone fragment, damaged by reuse, but possibly a low bun-shape. There is also one fragment of greensand that is probably from a millstone, the only indication of the mechanisation of flour production. This does not necessarily imply that there was a mill on or close to the site, as the stone has been reworked, and may have been brought to the site as building stone. The Purbeck marble 'quern' is perhaps more likely to be a table top, or an architectural fragment.

Other objects concerned with food preparation are scarce, apart from ceramic mortaria, the standard Roman mixing bowl. There is one possible fragment of a stone pestle, but stone pestles and mortars cannot have been used to any extent in Essex, as they are very rare on rural sites, despite a fair number having been found in Colchester (Crummy 1983, 76-7). A number of the larger knives were probably used in butchery and food preparation, though there are no complete cleavers or choppers. The evidence for meat preparation is complemented by the presence of butchery marks and collections of butchery waste among the animal bone assemblage.

Preservation of meat by salting is obliquely suggested by the large assemblage of salt briquetage. A number of fragments from ceramic cheese presses were found, and salt would also have been used in cheese-making. It is possible that the wooden 'sword' SF2758 was also used in dairying.

Cooking processes are represented by a number of metal vessels and their fittings, and utensils used in cooking, some of which will be mentioned in more detail below. The main cooking styles that can be identified are boiling and frying. Evidence for the use of cauldrons rests on three swivel loops of the type found in cauldron chain assemblies, two from later/latest Roman contexts, and large links that may be from the accompanying chains. The cauldrons themselves have not survived. Other metal vessels present include copper-alloy skillets, and iron frying pans.

Knives are the most common iron finds from Roman sites after nails, and most would have been multi-purpose tools, used for preparing food and eating, as well as in everyday life in general. It would be over a millennium before specialised table knives emerged, accompanied of necessity by table forks. Unlike the rounded ends of modern table knives, most Late Iron Age and Roman knives had pointed tips, which could be used to spear food in the absence of forks. There is a single, rare, example of a Roman fork from Elms Farm, but it is very unlikely that it was used for eating, and it is possibly a very small pitchfork.

Flesh-hooks with two or more curved prongs would be used to serve meat from the cauldron or cooking pot, and there is also a possible iron ladle bowl from the site.

Seven spoons were found, five made from copper alloy, two from iron, and one from bone. The assemblage included one outstanding copper-alloy spoon, with a zoomorphic head on the handle, and part of what must be a matching spoon, both unstratified (Figure 455, no. 1). This is, quite literally, a 'table spoon', since the shape of the handle copies that of a curved table leg, complete with foot and animal head. The mouth is open, suggesting that the head is that of a panther, generally shown as snarling on table legs; Liversidge (1955, 42) illustrates a similar beast adorning a marble table leg from Pompeii. There are few parallels for the decoration on this object, which must be later Roman.

Although only a small number of spoons was found, it should be borne in mind that they could also be made from wood, and were likely to have been far commoner than the archaeological record suggests. Earwood (1993, 115) mentions that wooden ladles and spoons are fairly common finds from Roman and early historic sites, though there are none among the small group of wooden objects from Elms Farm.

There was a fairly large assemblage of metal vessels from the site, including a hoard of five pewter vessels, and a complete copper-alloy jug; shale vessels were also well represented. Glass and ceramic vessels are considered elsewhere.

The group included one definite fragment of a pre-Roman copper-alloy vessel, a cast, vine leaf-shaped escutcheon, probably from a large bowl (Figure 462). It is very similar to a pair of escutcheons from the Lexden tumulus (Foster 1986a, 63, nos 6 and 7) which were probably deposited c. 15-10 BC. The Elms Farm escutcheon was unstratified, as was a further example from Essex, found at Fingringhoe. The type is continental, Augustan in date (Foster 1986a, 176-7), and clearly would have been a luxury item. Rather than being traded directly to Elms Farm, it may have been a gift from the over-chief, perhaps even from the occupant of the Lexden tumulus himself. This individual must have been an eminent member of the Catuvellaunian nobility, possibly Addedomarus, several of whose coins were found at Elms Farm.

Several vessels must have arrived at Elms Farm around the time of the conquest. Two fragments of copper alloy are probably from cup handles dating to the 1st century AD, and possibly pre-Roman. One is likely to have been imported, the other, from a Period 2 context, is possibly a local product (Function 4, nos 44 and 38). Of similar date is a foot from an imported copper-alloy bucket. A more elaborate foot of the same type, found at Heybridge earlier this century, is now in Colchester Museum (Eggers 1966, no. 35 and Abb. 58), and another example came from the Boudiccan destruction debris at Colchester (Crummy 1983, 73, no. 2051). Composite vessels of this period are represented by two iron fittings; one part of a binding strip from a wooden vessel, the second an iron handle mount from a vessel either made from thin copper alloy, or perhaps a wooden vessel with sheet copper-alloy decoration.

The copper-alloy vessels of the Roman period of the site are mostly fragmentary, and include a skillet handle, a strainer base, probably from an imported vessel, a strainer handle, rims from both cast and sheet metal vessels, and decorative mounts. The only complete vessel (though somewhat battered) was a copper-alloy jug, probably a votive deposit in a mid-Roman pit. The jug itself was unprepossessing, but the handle was a very fine and elaborate casting, with the upper part in the form of a lotus bud, and the terminal in the shape of a human foot, only the third such handle from Britain. This was a continental import, probably dating to the first half of the 2nd century, and probably made in Pannonia. Jugs with foot-handles can be divided into two groups, and this is the only example of the eastern type from this country. It has been suggested that the western type jugs were deliberately made as ritual vessels, as they derive mainly from sanctuaries, and other contexts associated with water. The eastern type, on the other hand, has been principally found in graves. There is too little evidence from Britain to ascertain whether the deposition of foot-jugs follows the continental pattern, but at Elms Farm, at least, use as a ritual vessel seems likely.

Vessels made out of iron must have been far more common than the archaeological record suggests, since the thin sheet from which they were made corrodes so readily. Even where it is possible to identify fragments as vessels, it can be difficult identifying the form. The site produced an almost complete frying pan, a very rare find that survived only because it had been held together by a thick, pebbly concretion; however, there were fragments from at least one other frying pan, probably two, suggesting that they were in fairly common use. The type is discussed by Manning (1985a, 104), who notes that most are later Roman, and the only stratified fragment from Elms Farm is from a latest Roman context. The only other definite fragment of a vessel primarily made of iron is the rim of a square or rectangular vessel, from an Early Roman context. Iron handle mounts are more abundant, either plates with perforated lugs, or strips with terminal loops, of the type found on buckets. A single example of a bucket handle came from a mid-Roman pit.

The five pewter vessels, like the copper-alloy jug, were deliberately deposited. This small hoard of two plates and three hemispherical pedestalled bowls or dishes was found in a mid-3rd to mid-4th-century pit in Area H (Figure 186). The group was nested when found, and had probably been buried in either a cloth or leather bag, or a wooden box, no trace of which now survives. One of the bowls has a Chi-Rho scratched inconspicuously under the rim, probably by the maker. The evidence suggests that pewter hoards can be either ritual deposits, or pieces hidden with the intention of future recovery. The situation is slightly ambivalent at Elms Farm, as the group has characteristics of a manufacturer's hoard (i.e. intended to be retrieved), but the context of deposition, associated with a headless horse skeleton, suggests ritual activity. In this case, the vessels may have been either personal or temple treasure.

There were fragments from ten or eleven shale vessels, an unusually large assemblage for this part of the country. Although the source of the shale was not identified petrologically, it is likely that it is Kimmeridge shale, and that it was brought to the site as finished objects. Crummy (1983, 71), for example, notes only five vessel fragments from the Colchester excavations, together with parts of three trays. Most of the vessel fragments are from early to mid-Roman contexts, with only one fragment from a later Roman context. A single body sherd is from a possible Late Iron Age context (post-hole 9140, Area D). Although shale artefacts were in widespread use at this time, there are very few Iron Age finds from Essex. The only assemblage of any size is from the Airport Catering Site at Stansted (Major 2004a), which produced eight fragments, all from vessels.

The distribution is strongly concentrated in Area H, with eight of the fragments coming from the area. Three of these were platter rims of very similar form, which could be parts of the same platter, as the low kerbs round the edge are the same width on all of them. Even if they are from different platters, it seems likely that they were part of the same consignment of vessels. The form of the edge is very unusual; most platters have beaded edges, as does the only other platter fragment from Elms Farm (SF2874). None of the fragments has a foot-ring surviving, so there is a possibility that they are something other than platters. However, there is slight dishing evident, which would rule out use as a tray, and the diameter seems too small for a tabletop.

The finds from Elms Farm provide little information on what the furnishings of the houses would have looked like, either in the Late Iron Age or the Roman period. Most of the furniture would have had been based on organic materials, which have not survived. Frames would have largely been wooden, although these were frequently embellished with decorative metal fittings and bone inlay. Mushroom-headed tacks, of which a number were found, are particularly associated with upholstery nowadays, and may have been used in the same way in Roman times. Basketry chairs are known to have been used from the Iron Age onwards, and one of fragments of pipeclay figurine from the site (SF8420) depicts a Mother Goddess seated in a high-backed wickerwork chair. Soft furnishings such as hangings and cushions, mattresses and mats have left no trace of their existence.

Direct evidence for furniture at Elms Farm is somewhat nebulous. An eroded, circular slab of Purbeck Marble, from a Late Roman context, may have been a table top (or perhaps a table top that was subsequently made into a quern). Liversidge (1955) notes that all the tables depicted on Romano-British sculptural reliefs have round tops and three legs, suggesting that this was by far the most common form of small table found in the province. There are certainly numerous examples of shale tables of this form. The legs of such tables were frequently adorned with features such as the panther found on the spoon handle mentioned above.

Other possible furniture fragments are an iron bar that may be a brazier or tripod leg (an alternative use as a delicate punch could be postulated), and a mount, in the form of a lion foot surmounted by a winged lion's head. The latter object echoes on a small scale the common form of Roman table leg, with a lion foot and animal head, and is a fully Romanised piece. It may have been part of the leg of an object such as a tripod, or possibly a vessel foot. A large hollow knob, from a Late Roman context may have been an element from a piece of furniture, such as the leg of a couch (see, for example, Richter 1966, pl. 542, for a bronze couch leg from North Africa, which includes a broadly similar element).

The use of chests and boxes for storage is clearly indicated by the number of box fittings found, items such as box-rings, drop handles, decorative studs of types frequently found on boxes, and angle brackets. Chests appear to have been made on site, at least during the Early Roman period, since many of the ceramic metalworking moulds found are probably for casting box-rings, which often had distinctive circumferential ribbing at that time. Many of the keys found would have belonged to chests rather than doors. Cupboards would have been used for storage as well, but we know comparatively little about their fittings, as, unlike boxes, they were not used in burials. However, they would probably have had similar decorative fittings to boxes, and may have also been lockable. Despite our preconceptions of the past being a more honest place, the ubiquity of keys on Roman sites suggests that security was an important consideration; not only the security of the house as a whole, but the ability to secure items of value within a locked chest or cupboard. This may have been particularly relevant for the temple complex, where, no doubt, there was a considerable amount of relatively valuable material stored.

In common with most rural sites, the evidence for artificial lighting is sparse, consisting of a few fragments of ceramic lamps, lead candlesticks, two possible pieces of pottery candlesticks, and an iron hanging lamp. No wall-mounted iron candle-holders were found. It has to be assumed that most lighting was in the form of torches or rush-lights that have left no archaeological trace.

The iron hanging lamp was one of the grave goods in boxed cremation 12203. Hanging lamps are fairly commonly found in Early Roman graves. Drury (1978, 99) notes that they occur in relatively rich, to rich, graves, and lists some of those from Essex, including the Bartlow Hills. To these must be added a rich burial from excavations at Stansted Airport (Havis and Brook 2004, Cremation 25).

The three fragments of ceramic lamp are Early Roman, dating from the mid-1st century AD to the early 2nd century AD, and comprise one picture lamp, one open lamp, and one factory lamp. The two lead tripod candlesticks are likely to be 2nd-3rd century, based on dating evidence from elsewhere. They are of a form first noted by Major and Eddy (1986), who, however, failed to identify their function. A complete and undistorted example from Colchester Royal Grammar School (in Colchester Museum) was subsequently identified by Mr P. Barford as a candlestick. Although initially considered to be of possible Christian significance, this is now thought unlikely. Candlesticks with a similar pattern have been found at Woodcock Hall, Norfolk, Canterbury, Kelvedon, Essex, and Colchester, and it is likely that they all came from the same workshop. This has not been located, but an East Anglian source is very likely, and the workshop could even have been at Elms Farm.

One of the two possible pottery candlesticks is illustrated in the pot report (Figure 299, no. 111). It is in a sandy grey ware, and dates to the later 3rd-4th century.

This category is poorly represented, and contains only sixteen bone and three glass counters, a number of ceramic discs that may be counters, and two dice, one made from bone, and one from lead (Table 62). Fourteen of the bone counters came from a single cremation (12203: the counters are described with the other finds from the cremation). They were burnt and fragmentary, and are unlikely to represent a complete set. Most of the material in this category came from Roman contexts, with the exception of three pottery discs from Late Iron Age/transitional contexts.

| Object Type | Lead | Glass | Bone | Pot | Tile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counter | 3 | 16 | 24 | 7 | |

| Die | 1 | 1 |

The number of bone and glass counters is not unusually small for a site of this size and type. Where large numbers of counters are found, it is often due to the presence of groups of counters, such as the bag of 126 counters from a barrack-block at Ravenglass fort (Potter 1979, 75-87). The use of purpose-made counters in board games is a Roman introduction, and sites in Roman towns tend to produce much larger numbers of counters than rural settlements. This may reflect a greater degree of Romanisation, or at least a more cosmopolitan milieu, in which the playing of 'foreign' games is more widespread among the population.

In fact, Elms Farm probably has more bone and glass counters than any other large rural site in the region; there were twelve from Gorhambury and nine from Baldock. However, when the fact that most of the Elms Farm counters came from a group is taken into account, it can be seen that the presence of a relatively large number of counters is unlikely to be of significance at this site. Colchester, the major town of the area, has at least 120 (published examples from Crummy 1983, and P. Crummy 1992), which puts the Elms Farm assemblage into perspective.

It may be noted here that at the temple at Henley Wood, forty bone counters were found, and it was considered possible that their deposition formed part of a ritual activity. This is an unlikely scenario at Elms Farm; only one counter came from the temple area.

The ceramic discs, fashioned from pot or tile sherds could have been used in a number of ways (not necessarily connected with pastimes - the larger ones may have been used as pot lids. The smaller, neatly finished examples are most likely to have been counters or playing pieces. Unworked pebbles could also have been used as counters, but they are impossible to identify as such archaeologically. There is evidence from Colchester that graduated sets of discs were used as stacking toys, and they may also have been used in throwing games.

Dice are far less common than counters, but, like counters, tend to be found in larger quantities on urban sites. By way of comparison, Gorhambury produced two bone dice, Baldock none, and the Colchester sites cited above had twelve. Dice made in materials other than bone are extremely rare, so the lead die is an unusual find. The only other examples known to the writer are both from Bancroft villa (Williams and Zeepvat 1987, 146, no. 203; Bird 1994, 347, no. 311). Small pottery beakers could have been used as shakers for the dice.

Another object that might belong to this category is the copper-alloy jointed figurine leg (SF5806), which for convenience has been included with the other figurines. It could be from a doll, although surely from the Roman equivalent of the best porcelain doll, which could only be played with on Sundays.

The paucity of finds in this category is unlikely to be a true reflection of the place of recreational activities in the settlement. Most of the objects that fit into this category could be made of wood - dolls, musical instruments, playing boards - and therefore have vanished from the archaeological record. The only representative may be the wooden 'sword' from well 8188, and even this could be utilitarian.

The fabric of the buildings on the site was represented by a variety of materials; burnt daub, tile, mortar and opus signinum, wall plaster, tesserae and window glass (Table 64), as well as the fastenings and fittings (Table 63) used to hold them together. Some of this material existed in large quantities; there was over 7 tonnes of Roman tile collected, and 316kg of burnt daub. In contrast, there were very small assemblages of wall plaster and window glass.

The nature of the buildings of Essex has always been influenced by the available raw materials. In particular, the county lacks building stone, though clay is readily available. Timber, wattle and daub, and tile were the normal building materials in Roman Essex. All good building stone, and much of the coarse stone rubble, derived from outside the county, and consequently little is found outside the major towns. Elms Farm is no exception.

The excavated evidence for the buildings suggests they were of timber-framed construction, as evidenced by the post-holes and beam-slots.

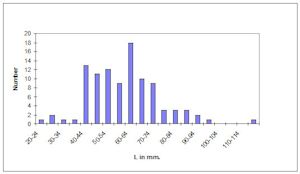

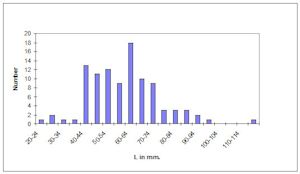

Some of the nails may be regarded as structural. Complete nails were relatively rare, forming only 19% of the assemblage (excluding hobnails). There were few large nails. Two samples of 100 type A nails from different areas of the site gave average lengths of 59mm and 57.6mm. In both cases, only one nail was greater than 100mm in length. Figure 507 shows the distribution of lengths from a sample of 100 from Areas K, H and J.

For the site as a whole, only sixty-eight nails with a length greater than 100mm were recorded, some incomplete. The largest complete examples were a type B nail (square head) from a Period 3 layer in Area M, and a type TT (truncated conical head) from a Period 4-5 layer in Area K, both with a length of 170mm. There were no examples as large as, say, the largest from the Inchtuthil assemblage, which ranged from about 230-370mm in length, and which were clearly used for joining heavy timbers (Angus et al. 1962, 957). At Elms Farm, the lack of very large nails and relative scarcity of fairly large nails suggests that the use of nails with heavy structural timbers was rare on this site. Most of the nails could be from joined objects such as boxes and furniture.

There is, however, some evidence for structural use. The lining of boxed cremation 12203 may have been fixed to the sides of the cut using nails. Two sizes of nail appear to have been used in the construction; the larger ones have round heads with diameters of 20-23mm, with lengths of about 110mm, while the smaller nails have heads with diameters of about 15mm, and are about 90mm long.

There was also a group of nails from the temple foundation trench (5555, segment 5767, contexts 5512, 5562 and 5564) which appeared to be located at fairly regular intervals, and therefore might relate to the structure. Ten nails were collected from the segment, though not all were plotted, and only one was complete. The complete nail had a length of 79mm, not large enough to be a major structural nail, but potentially useful for nailing something to the wall. It was slightly bent at the point end. A bar fragment from the context (SF4726/4728) may be the shaft of a large nail at least 170mm long, which would make it the largest nail from the site. A second bar fragment (SF3233) is unlikely to be part of a nail. The plotted nails appear to be in the stake-holes within the trench, and, at the level at which they were found, would have been below ground level. It is possible that they are merely chance introductions into the fills of the stake-holes, either during construction of the building, or during demolition. None of the other excavated segments produced nails.

Other fixtures and fittings included carpenter's dogs, iron staples and the pivot for a door.

The walls of most buildings on the site were made from wattle and daub, and burnt daub was recovered from 659 features. The daub derived from hearths and ovens, from the burning of timber-framed buildings with wattle and daub infill, and from accidental burning of structural daub. The material was found in all periods, but the major period of deposition was the 2nd-3rd century, because of a large amount of daub associated with Building 54 in Area G (of which more, below).

Wattle impressions and variations of surface treatment are present on some pieces. The wattles generally had not had the bark removed, and ranged from 12mm to 36mm in diameter. There were also imprints of the squared timbers of wall studs, with the texture of the wood surviving on some pieces. The only measurable one was 64mm across.

Two distinctive forms of keying were present on the surfaces of some pieces. One form of keying, present in several Period 2 contexts, was unassociated with any particular building. The surfaces were impressed with chevrons and lattices made with a thin metal or wooden blade 60mm wide. There are some similarities to the keyed daub recovered from the Boudican destruction of Building 79 in the Culver Street excavations, Colchester (N. Crummy 1992b, 253-4).

In total, 281 pieces of daub bore roller-stamped chevrons and diamonds, a form of keying that has been found at other sites in Essex including Great Chesterford, Gestingthorpe, Colchester, Billericay, Wickford and Mucking (Russell 1990, 88). Although found at a few sites in other parts of the country, most roller-stamped daub is from Essex, north Kent and London, and the technique can be regarded as a regional one, in use in the 1st-2nd centuries AD (though it is worth noting that it has also been found on the continent, so is not a purely British phenomenon). Its use is not confined to a single type of site - it is found at major towns, small towns and villas. In common with the elaborate patterns of roller-stamped box flue tiles, the patterning on the daub is likely to be for keying plaster rather than a decorative effect meant to be seen. Most of the roller-stamped daub came from the area of Building 54, which was constructed in the late 2nd to early 3rd century, but its presence within the foundation trench of the building suggests that it was not necessarily used within that building.

By weight, 45% of the total amount of daub from the site came from Building 54. This was the only building on the site with a substantial amount of associated daub, partly due to the fact that the building burnt down, and partly due to a curiosity of its building technique. A mixture of earth and burnt daub from (presumably) a different building (i.e. one not burnt as a result of the fire in Building 54) had been used as packing round the posts in the foundation trench. The bottoms of the charred wooden posts could still be seen in situ within the trench.

The use of stone for structures on the site was not common, and there is little evidence for the use of shaped building stone. Stone rubble was used in the foundations of the temple precinct wall, in the plinth of the temple, as footings for Building 63, and in some oven structures and hearths.

Three pieces from the site may be carved architectural stone. One piece is a possible door pivot stone, the second is a possible decorative slab, and the third is a piece with a more complex shape. The latter piece is from the vicinity of the temple. All are definitely or possibly made from stone of the Millstone Grit series.

Samples of the stone used as building rubble were collected, some possibly crudely shaped. It included stone types that are not local to the site, in particular, Kentish greensand and septaria, the latter being the commonest building stone on the site. Septaria is found in deposits along the north Essex and Suffolk coast, and was used extensively in Roman Essex. Greensand was used as a building stone in Essex from soon after the conquest, and was used extensively in the temple of Claudius at Colchester (Williams 1971, 172). The greensand at Elms Farm, however, may have arrived on site primarily as ballast in trading vessels, rather than being deliberately imported as a building stone; the pieces of tufa were probably also from Kent. With both septaria and greensand, it is difficult to tell whether it has been deliberately shaped: in the case of the septaria, because it tends to break naturally into irregular blocks, and in the case of the greensand, because the surface has usually eroded. Some of the tufa certainly seems to have been cut into rough blocks, and it is likely that this was true of the greensand as well. Septaria does not cut well, and was probably never neatly trimmed.

Comparison of the proportions of contexts containing septaria and greensand suggests that their chronological distribution was similar; both types occur in small quantities in Period 2 contexts (though probably not used as building stone at that period), and exhibit a drop-off in deposition in Period 5.

Utilisation of stone for coarse building material would have been opportunistic, given the lack of good building stone in Essex. Other stone used as building rubble includes flint nodules, various sandstones (probably mostly derived from local erratics), shelly sandstone, quartzite and sarsen. Table 65 lists the number of contexts from which unworked stone of each type was collected; the list may include some non-building stone, such as the burnt flint nodules.

There was also use of tile in some structures (leaving aside the question of roofs for now). Some 2.7 tonnes of flat tile was recovered, of types normally used for structural elements such as floors and bonding layers, but not all of this had necessarily been used in buildings, and other tile types (roof tile and box flue tile) had also been utilised in structures. Tile that had definitely been used in structures accounted for 14% of the tile from the site. It seems to have generally been used in the same sorts of structures as the building stone, that is in ovens and hearths, as packing in foundation trenches and post-holes, and in the precinct wall.

The tile-built ovens usually had a tile base, with side walls made from horizontal layers of tile. Where there was any sign of mortar, a clay-based mortar had been used. Lydion (flat rectangular tiles) were most frequently used, but tegulae (roof tiles) were present as well. None of these ovens survive to any height, so the form of the superstructure is unknown.

There was occasional use of tile for post-packing, and post-pads. Some foundation trenches also contained large amounts of tile, but in many cases this may represent backfilling after demolition rather than use in foundations.

The temple precinct wall was principally constructed from stone, but repairs had been made in Period 4-5, using tile. Two courses of unarticulated tile from repairs made to the precinct wall were retained for examination (context 21997/22079). The tile had been bonded with white mortar, and was mostly brick, probably all lydion, with a few pieces of tegula and imbrex. Some of the brick had traces of both white mortar and opus signinum, the latter material always occurring on the edge of the tile. It can be suggested that the wall was originally faced with opus signinum, although it is possible that the tile was reused, and that the opus signinum represents traces of its former use.

The only other bonded tile came from pit 10763 (Area F), which contained a block of seven courses of tile, possibly part of an oven or a plinth. In Building 63 a vent had been formed in the dry-stone (flint and septaria) wall footing, using bricks set vertically on a base brick. The base of the vent was below the level of the door. The purpose of the vent is unclear; there was no sign of sooting or burning, so it doesn't seem to be a 'flue' as such. If a drain, there seems to be nowhere for the water to run to, apart from straight into the soil round the building. Possibly it was an inlet for a water pipe. The purpose of the building is unknown, but the vent may be relevant to that purpose.

There was 117kg of box flue tile from the site, including some large pieces of voussoir tiles, but in the absence of any evidence for a hypocaust on the site it has to be assumed that the box flue tile was not being used for its normal purpose. Some of the box flue tile had internal sooting, showing that it had been used in a hypocaust, but it must have been robbed out from a building elsewhere.

Few of the buildings and other structures employed mortar in their construction. The mortar was sampled on site, so quantitative analysis not very meaningful apart from giving a general idea of relative quantities. However, it was only considered worthwhile taking samples from thirty contexts. Nearly two-thirds came from the temple precinct, including the plinth of the temple, the precinct wall, and Building 63. A few of the tile-built ovens employed 'proper' mortar, as opposed to clay-based bonding material, but the mortar seems to have been used sparingly, and the structure of the ovens was not fully bonded.

Most of the opus signinum from the site came from late/latest Roman contexts in Areas I and J, some still attached to bonding tiles. Opus signinum is considered to be mortar with varying quantities of crushed brick and/or tile added during mixing. The resulting material was used structurally, for instance, in roofs, walls and mosaic bedding, and decoratively for floors and bath linings. The evidence from Elms Farm suggests limited use in structures in the temple area, as flooring (though not as mosaic bedding), and possibly as a facing for the precinct wall.

Some evidence for the use of glass in windows was recovered, consisting of ninety-six fragments of window glass, all from post-conquest contexts. Most was cast, but there were two pieces of later Roman blown glass window panes. Half of the fragments recovered come from peripheral Area R, nearly all from Period 4 contexts. The authors of the glass report suggest that this was dumped from elsewhere, a supposition supported by the occurrence of large amounts of Roman tile in the Period 4 contexts containing glass. Roman window glass in Essex, outside Colchester, is fairly uncommon and always appears to be associated with an identified building. It is reasonable to suggest therefore, that a substantial building existed not too far from the excavated area at Elms Farm, and that the window glass in Area R derived from it.

There was evidently very little (if any) use of window glass on the excavated site. No area, apart from R, has more than eight sherds, and there was no association with a particular building.

Evidence from elsewhere suggests that the keyed daub mentioned above was probably on the interior of the walls, and that it would have been covered by plaster. There is very little evidence for the plastering of walls in the settlement, and none associated with the keyed daub.

A small amount of painted wall plaster was recovered from eight contexts in Areas K and N. The total surface area was 1432cm². Most of the fragments (78% by area) were from an undated cleaning layer 4881 in Area K, and the remainder was from a re-cut pit in Area K, and a pit in Area N, both dating to Period 4-5. The small amount from Area N was probably from the same source as the material from K.

The decoration divides into two groups: plain colours; and colour combinations on a white ground, with bands, stripes and beads represented in various colours. Although there is insufficient material to suggest any decorative schemes, the room (assuming that the material comes from a single room) was probably painted with large areas of plain colours divided into panels by contrasting stripes. With the possible exception of the beads, the design is purely geometric. The beads may have been placed at the corners of the panels, as in the reconstruction of the early 3rd-century wall decoration of Building XXII, Corridor 5 at Verulamium (Liversidge 1984, 126).

The painted plaster from this site is evidence for a Roman building of moderate status. It came from an area adjacent to the temple precinct, and probably derived from either the temple or an associated building. There is certainly no evidence for wall paintings having been widespread on the site.

Little evidence of built interior floors survived. Some of the opus signinum may have been from floors, as fragments from pit 13358 (Area I) incorporated possible floor surfaces. There was a single example of an opus spicatum brick, a type used for making herringbone-patterned floors, though whether it was actually used in this way on this site is debatable. Opus spicatum bricks are relatively rare. Local examples include finds from Colchester (N. Crummy 1992b, 256) and from the temple precinct at Great Chesterford, seen by the writer.

The largest group of floor material was the tesserae, of which there were 9831, made from tile and pot. This represented a total surface area of 88,282cm², i.e. an area slightly less than 4.5x2m. The majority of the tesserae were made from tiles of various colours, with occasional use of suitable pieces of pottery. The pottery is a very minor component of the assemblage (twenty-five sherds), and is unlikely to be significant, merely indicating that that the tessera makers were using any suitable material to hand. There was a single possible stone tessera.

The average size of tessera from Elms Farm was 30x30mm, consistent in size with use in coarse tessellated pavements, rather than figurative pavements, which normally use smaller tesserae c. 10-15mm square. Some tesserae were rectangular, usually about twice the length of the 'standard' tessera; others were rather irregular, but most were more-or-less square. Most of the tesserae had traces of wear, with mortar surviving on some, showing that they had actually been used in floors or other prepared surfaces.

The tile used was predominantly orange/red in colour, with small amounts of cream/buff and grey tile. The pottery and amphora were mostly in cream or buff fabrics, with a few grey and red sherds. The dominance of orange/red tesserae suggests that there was little, if any, patterning present. The very small amount of grey tesserae makes it unlikely that this colour was used as a pattern element. However, the cream/buff tesserae are present in sufficient numbers to suggest that they could have been used to pick out a simple pattern, such as a linear border, although it cannot be ruled out that they were just used randomly.

Tesserae were recovered from all areas of the site, but in small quantities apart from Areas J (79% of the total number) and H (15%), and the seven largest groups (excluding machining contexts) are from Area J. The greatest numbers of tesserae were deposited in contexts dated to Period 5-6, with a lesser peak in Period 4. The distribution across the site suggests that those from the later contexts largely came from the destruction of a floor in Building 45, which retained a small part of the floor in situ. It is more difficult pinpointing the source of the tesserae from Period 4, but the distribution suggests a building or buildings somewhere in the vicinity of the temple.

It can be surmised that most roofs were thatched, though there is no direct evidence for this. The very large assemblage of Roman brick and tile (over 7.1 tonnes), including a substantial amount of roof tile - 2.6 tonnes of tegulae and 695kg of imbrices - but at least some of this had been used as a general building material in structures such as ovens. Only 9% of the total number of sherds was directly associated with buildings, and there are no collapsed roofs, or large dumps of roof tile that might indicate which buildings might have had tiled roofs. No correlation of the deposition of tegulae and imbrices was detected, and it may be that the roof tile was being brought to the site merely as general building material, and that none of the roofs were tiled.

The function of the objects labelled 'chimney-pots' is still uncertain, so their inclusion in this section is arbitrary. Past suggestions include roof finials, ventilators and votive lamp chimneys. They were first discussed at length by Lowther (1976), who termed them 'chimney pots or finials', and distinguished two groups: group A were made from pottery fabrics, and group B from tile fabrics. The use of different fabrics may be significant, with those in pottery fabrics potentially having a different function. Certainly, the use of tile fabrics for group B suggests that they were likely to be roof furniture, borne out by the existence of an example from Norton, E. Yorkshire, which incorporates an imbrex at its base. The general lack of sooting, however, suggests that they may be ventilators rather than chimney pots as such. The group A 'chimney pots', which are in finer fabrics and which tend to be more elaborate, would seem like better candidates for votive lamps or incense burners, but again, there is little evidence for the sooting one might expect on the inside of a lamp cover - more so than on a chimney pot, since a lamp cover would be in closer proximity to a source of heat and smoke.

There were seven fragments of 'chimney pot' from Elms Farm, from six contexts, none of them very large. They were all in tile fabrics, and none had sooting. This small group of 'chimney pots' add little to the debate. Although there are examples from other temples, they can be found on a variety of site types, and none of the Elms Farm fragments are from the immediate vicinity of the temple. They are therefore unlikely to be connected with religious ceremonies. Their distribution is very scattered, and they cannot be tied in to a particular building, or even a particular area of the site. They are also scattered chronologically, occurring in contexts dated from Early to Late Roman.

The artefactual evidence for water management on the site consists of fragments of ceramic pipes, and a number of iron water-pipe collars from wooden pipes. The water-pipe collars came from a late 3rd to 4th-century ditch in Area R (25270, seg. 12027, Group 968). They were fragmentary, but it could be determined that at least three collars were represented. Mineralised wood from the pipes was present on the collars, and the position of the collars suggested that they were in situ. The wooden pipes would have been c. 1.8-2m long.

There is further evidence for water management in the same area; the bottom of Ditch 25271 (Group 969) was lined with wooden planks, and it was clearly not just a boundary ditch, but part of an organised water management system, draining into the watercourse to the south.

The presence of a wooden water-pipe on a site such as this can be considered unusual, as almost all the evidence for such pipes comes from towns or villas. Both the pipe in Ditch 25270 and the planked 'drain' in Ditch 25271 appear to be associated with a building to the north of Area R, and not with the main part of the excavated site. Given that other artefactual evidence (the window glass and tile in particular) suggests the presence of a major building in the vicinity, it seems reasonable to suggest that these two features form part of a water management system associated with that building. More specifically, it can be suggested that the building was a bath-house, located in the unexcavated area immediately to the north (41 Crescent Road and the adjacent plot). The pipe would have provided running water to the bath-house, with Ditch 25271 acting as the drain. Although the pipe slopes up towards Crescent Road, if it was fed from a raised cistern, it would be possible to create a large enough head of water to force the water up the pipe. The square cut to the east of Ditch 25270 (12061) could then be interpreted as the site of the base for the cistern, filled from the adjacent palaeochannel. The water could have been raised mechanically from the palaeochannel, and evidence for this may well survive in the unexcavated area to the south of 12061.

A very similar arrangement of a wooden pipe and a timber-lined drain at an angle to each other was found at the Little Oakley villa, adjacent to Building 3 (Barford 2002, 24 and fig. 16). The date of the features is similar to Elms Farm, and the wooden pipes used were of similar length. Paralleling the arrangement at Elms Farm, both the drain and the water-pipe sloped away from the building, and a raised cistern would have been required to act as a feeder for the pipe. The cistern would have been outside the excavated area. Barford thought that Building 3 probably contained a bath suite. However, the evidence from Little Oakley is not easy to interpret, and neither the layout of the water management system, nor the nature of the room from which the pipe and drain emerged, is clearly understood. Nevertheless, it provides an interesting comparison with Elms Farm.

Fragments of nine ceramic pipes or tubes came from eight contexts. They were in tile fabrics, except for an octagonal-sectioned pipe in a pottery fabric (sandy grey ware). The latter pipe is paralleled by a hexagonal-sectioned one from York (Brodribb 1987, 85), although the York pipe is in a somewhat thicker tile fabric. The contexts containing pipe fragments vary in date from Early to Late Roman, and are concentrated (if one can say that about such a small group) in Areas E and F, which produced six out of the nine fragments. Ceramic pipes were most commonly used for conveying water, although there is no evidence of how they were utilised at Elms Farm. They may, like much of the brick and tile, have not been used for their original purpose on this site. It remains conceivable, however, that ceramic pipes were in use, presumably somewhere in Areas E and F, starting before about AD 160, and therefore earlier than the wooden pipes from Area R. The small amount of ceramic pipe retrieved suggests that they were not used extensively on the site.

A small group of objects, twenty-two in all, comprises the ironwork that can with some certainty be linked to agricultural practices (Table 66). The agricultural tool kit of the Romans would undoubtedly have included general-purpose knives and other blades that could have had other purposes, subsumed in this report into the general tool category. Many agricultural implements, such as rakes, could have been made entirely of wood, with no inorganic components. Iron rake prongs are infrequent finds from Roman sites, but were probably more commonly used than the archaeological record suggests, since they are very difficult to identify when broken. Some of the bar fragments from Elms Farm could be rake prongs, but they have not been included here.

| Object Type | Copper Alloy | Iron |

|---|---|---|

| Bell clapper | 1 | |

| Billhook | 2 | |

| Ox goad | 10 | |

| Pruning/reaping hook | 5 | |

| Shackles | 2 | |

| Scythe | 1 | |

| Blade fragment | 2 |

All the objects in this category from dated contexts are Roman, with the possible exception of the two shackles, which are from a Period 2-3 pit. The artefacts thus provide no evidence for Late Iron Age agricultural practices at Elms Farm.

The group includes objects associated with both animal husbandry (ten ox goads and an animal bell clapper) and arable farming (bladed tools such as pruning hooks). Also in this category are two slave shackles; while they are only loosely connected with animal husbandry, it seemed more appropriate to place them here rather than in, say, items of personal adornment.

Rees (1979, 4) poses the question of the significance of finds of agricultural tools from Romano-British temples. At Elms Farm, where there is both a temple and a settlement that presumably engaged in the normal rural practices of agriculture, it is difficult to disentangle the evidence. Six of the objects are from the Central Zone, but only one was actually from the temple precinct, a small curved blade of a type generally regarded as a pruning knife, from a late Roman pit (13873, Group 445). Use of such a blade in ritual practices cannot be ruled out, but is unproven. The Southern Zone yielded the largest number of agricultural finds, twelve in all, of which five came from Area M. This suggests a focus of agricultural activity in this part of the site, perhaps throughout the Roman occupation, as the group includes objects from all periods.

The environmental evidence for agriculture (animal bones, plant macrofossils, pollen) is presented in Section 4. Objects used in food processing, such as querns, are covered under FF4.

Given the location of Elms Farm, it was hoped that the site might yield artefactual evidence of the utilisation of marine or riverine resources. However, apart from the evidence for salt extraction, there was only a single object that was definitely connected with this category, a copper-alloy fish-hook from a mid-Roman pit. Fish-hooks are rare finds from Roman sites, although this is unlikely to reflect their true prevalence in Roman times. It is difficult to identify incomplete fish-hooks, and they were probably more likely to be lost during use than on a settlement site. They can be barbed or barbless, as this example, and are more common in copper alloy than iron.

Some of the lead weights may have been used as line or net weights, for either fishing or wild-fowling. The faunal assemblage includes a small amount of duck bones, some definitely wild rather than domestic, and estuarine birds such as the curlew and the grey plover. The few spearheads present on the site could have been used for hunting; they have, however, been grouped together with other possible military artefacts.

Salt production is indicated by a large assemblage of briquetage fragments, including vessel fragments, firebars and supports. There was a total of 6641 pieces (219kg), making it the largest assemblage of 'inland' briquetage from the county.

The vessels were all fragmentary, but are all likely to be the rectangular, slab-sided evaporation troughs known from excavations at Red Hills (the primary salt production sites on the salt marshes) in the Blackwater estuary and elsewhere. The Red Hills on the Blackwater seem to have been abandoned by the end of the 2nd century AD (Fawn et al. 1990, 46), and the chronological distribution of the briquetage from Elms Farm reflects the rise and decline of the local salt industry (Figure 430).

Inland sites with briquetage are listed and discussed by Barford (in Fawn et al. 1990, 79-80) and Sealey (1995, 77), a total of twenty-three sites, nineteen of them in Essex. At the time of writing, the number of inland sites with briquetage is approaching seventy. However, at none of these sites is briquetage present in anything approaching the quantity found at Elms Farm. The next largest amount is from Chigborough Farm, Goldhanger (Major 1988c), a mere 19kg.

Various suggestions have been made as to why briquetage is found on inland sites. Barford (Fawn et al. 1990, 79-80) suggests, for example, that the salt could have been traded in the briquetage vessels, or that salt-impregnated briquetage was being specifically traded as salt-licks for cattle, or that fragments of briquetage were accidentally included in the salt blocks. Sealey (1995, 69) doubts that the material would have had enough salt content to make it suitable for use as salt-licks, but suggests that the pieces may be from briquetage used for secondary drying of salt that had become damp during transport.

As Sealey observed (1995, 69), the quantities of briquetage recovered from most inland sites are modest, seldom more than a dozen sherds, and virtually all vessel sherds. The sites with larger amounts are predominantly, though not exclusively, close to the coast (Table 67). The two sites that stand out in Table 67 are Stansted, approximately 36km from the nearest bit of coast, and Kelvedon, 12km from the coast. The sherds from Stansted are very small on average, 5.5g as against 32g for Elms Farm, and it cannot be considered an impressive assemblage, nor proof that the troughs were reaching the site unbroken. The Kelvedon assemblage includes relatively large sherds used as a pit lining, but no firebars.

There has been evidence from other inland sites that briquetage vessels were being used on the site; Barford (1988) cites the 'pink pits' at Mucking, and suggests that the briquetage found at Ardale School may have been used as such on the site. In addition, the presence of firebar fragments in some quantity at several sites (Elms Farm; Chigborough Farm, Goldhanger; and Palmers School Grays) also suggests that the briquetage was being used there. If the briquetage vessels were arriving at these sites merely as containers, there seems to be no reason why firebars and pedestals should be present in any quantity.

Most of the sites further inland have no hearth furniture in their assemblages, and there is no good evidence that the briquetage was being used there for its original purpose. Although it is possible to envisage that salt arriving at these sites may have required further drying (given the dampness of the English climate), there is no reason why this could not have been done in locally made ceramic containers, rather than in the special briquetage vessels only produced on the coast - and as far as we know, salt briquetage was only made on the coast. Nenquin (1961, 124) cites previous work on the Essex Red Hills, and comments that 'the fact that the pottery [i.e. the briquetage] was made on the spot can be seen from the chemical analysis of the local clay and of the briquetage'. Certainly, the briquetage from Stansted, for example, is visually no different to the briquetage from the Red Hills, and very different from the rest of the baked clay from the site. It is likely, therefore, that at the inland sites without hearth furniture, the briquetage was either arriving as fragments accidentally incorporated in salt cakes, or, at sites with larger fragments, possibly being used to transport the salt.

This latter scenario would be most likely at sites with easy access to the coast by river, though it seems more likely that if salt were being transported in ceramic vessels, jars would be more suitable, since their narrow necks are more easily sealed against damp. There is, indeed, documentary evidence for the transportation of salt in jars, albeit in Italy. Frayn (1978, 31) cites an anecdote by Frontinus regarding jars of salt being floated along the river at the siege of Mutina. The presence of coastally produced pottery on the inland sites with briquetage could be possible supporting evidence for the transportation of salt in jars. This aspect has not been fully explored for this report, but at Stansted, at least, such evidence is lacking (T.S. Martin, pers. comm.).

It is difficult to envisage salt being transported in its original evaporating troughs as far inland as, say, Stansted, and they would undoubtedly have been cumbersome to carry. In addition, the very fragmentary nature of the briquetage vessels, even at Red Hills, suggests that the vessels were broken at the production site in order to extract the salt blocks, a process with modern parallels in Niger (Gouletquer 1975). In his review of the ethnographic parallels, Nenquin (1961, 117) notes that 'everywhere salt is first pressed into salt-cakes before it is sold'. It is far more likely that the salt would have been formed into small cakes before being traded on, although evidence for salt-cake moulds is almost entirely lacking from the Essex Red Hills. The rectangular troughs, though large, may have served as moulds, or possibly wooden moulds were used, which would leave little archaeological trace. Small salt cakes would be far easier to transport, in bags or baskets.