Cite this as: Allison, P. 2018 An Introduction to a Research Network: the rationale and the approaches, Internet Archaeology 50. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.50.1

The 'Big Data on the Roman Table' research network, directed by Penelope Allison and Martin Pitts and funded by The Arts and Humanities Research Council, ran from June 2015 until November 2016 and brought together an international group of some 50 archaeological and science-based researchers, working in university, government and commercial environments, to address questions concerning the effective analyses of the large datasets of artefacts, found across the Roman world, and the eating and drinking practices associated with them. The central theme was the exploration and development of innovative analytical approaches for investigating the millions of tablewares that framed daily social interaction in different contexts and regions of this world during the early Roman Empire. This network, therefore, sets the agenda, at an international level, for the next phase of research into social practice in the Roman world using often readily available 'big data'. These data have been neglected in such approaches to date, in large part because of long-established conventions of Roman pottery studies, and the type of questions traditionally asked of such pottery remains, but also because of a lack of techniques for processing and analysing this wealth of archaeological data.

Across the humanities and social sciences interest in food cultures and their social organisation has been growing in recent decades. Concern for food- and drink-consumption practices has also been growing across the archaeological discipline (e.g. Jervis 2011; Mullins 2011; Collard et al. 2012; Steel and Zinn 2016). However, investigations of these practices for the majority of people living in the Roman Empire, and therefore our understanding of them and of the social and cultural connectedness and disconnectedness on which they inform, are limited and uneven. This network has explored how we can more effectively analyse the 'big data' that are the artefactual remains of these practices to identify the differing behaviours surrounding eating and drinking among the various groups of people from across the Roman world, in order to lead us to a better understanding of socio-cultural differentiation and its political implications across this world. Thus, it has proposed new ways of thinking and new tools that challenge current perspectives on the role of these remains in our investigations of Roman society.

Millions of artefacts associated with eating and drinking have been recorded by archaeologists since the eighteenth century and are the main 'big data' component from the Roman world. Despite this, Roman food- and drink-consumption studies are driven by discourses in ancient written sources, such as Plutarch's Table Talk, the satires of Juvenal and Martial, and the Cena Trimalchio in Petronius' Satyricon, which focus on elite urban dining practices, as socio-political settings for conspicuous display. Studies of architectural remains (structural and decorative) have also focused, somewhat selectively, on remains that might serve to demonstrate the elite foodways recorded in the written evidence (e.g. Dunbabin 2003; Leach 2004, 41-47). While this evidence provides important insights, it is largely silent on the everyday foodways of the vast majority of the population across the Roman world. More depth and detail, with greater social and geographical specificity and range, is provided by the extensive artefactual record, which is a more immediate record of the social relations surrounding food- and drink-consumption. If investigated more comprehensively and more critically, these artefactual remains can provide important, independent, and fine-grained information on the diversity of eating and drinking practices – everyday and habitual practices as well as feasting and ritual occasions – and the socio-cultural significance of these practices across the Roman world, as an essentially bottom-up approach to the varied experiences of phenomena such as imperialism and globalisation. However, most Roman foodways' research has focused on the food itself (e.g. van der Veen et al. 2008) and its availability (e.g. Richards 2014), and on cooking wares and food preparation (e.g. Swan 1999; Peña and McCallum 2009; Toniolo in press). Although understanding eating and drinking practices are fundamental to social history, the relevant artefacts, predominantly fineware pottery, and their potential to transform current discourses, have been largely ignored.

That said, the numerous artefacts used for eating and drinking across the Roman world have been well studied, especially the fineware pottery. However, such studies have traditionally used this material evidence as chronological indicators, and to inform on trade networks (e.g. Oxé et al. 2000; Mees 2007; Willet 2014; see also Price 2005 on glassware). These finewares, so fundamental to our understanding of Roman foodways, are often decontextualised for typological and chronological investigations of their production processes and geographical distribution. That is, their precise findspots, as evidence for their end use, have not been considered important and the widespread potential of these ceramic finewares for investigating a range of socio-cultural dynamics have not been fully realised (see Pitts 2015).

The main Roman ceramic tablewares – the ubiquitous red-polished terra sigillata and also local imitations – are found across the empire. This geographical spread has meant that these ceramics have been considered the standardised Roman finewares par excellence, and a measure for being Roman (e.g. Wallace-Hadrill 2008, 407-21). The most influential studies of these finewares to date concern the classification of forms and focus on the chronology of their production, from Dragendorff (1895) to Ettlinger et al. (1990). While such studies provide essential resources for identifying and classifying these finewares, most show little concern for their actual uses or for the socio-cultural significance of such uses. That said, some recent studies of Roman tablewares (e.g. Cool 2006) demonstrate that 'attention is shift[ing] from structures to artefacts' (Pitts 2014, 135) in investigating social practice. However, selected artefacts are used specifically, often to support perspectives recorded in ancient literature on, or in pictorial representations of, formal and festive dining, presenting a perception of universalised, normative, dining practice across the Roman world (e.g. Hudson 2010). More systematic approaches to this artefactual evidence are found in some studies of pre- and early Roman periods (e.g. Willis 2005; 2011; Dietler 2010, esp. 203-06, 244, 254; Pitts 2014). However, these studies are concerned with regional, socio-political questions and, again, more formal dining occasions.

Thus, despite their vast numbers, tablewares – particularly the mass-produced ceramic finewares but also metal and glass wares and other utensils – are chronically under-utilised in Roman social-historical investigations. The lack of critical consumption-orientated approaches stems not only from a lack of appropriate theoretical frameworks but also, in large part, to a lack of critical approaches to collating, quantifying, and analysing these data and presenting the results. The inconsistent and selective publication of pottery and pottery forms has often frustrated more holistic approaches to the users of this enormously rich dataset of relatively mundane artefacts (Cool 2006, 117). Also national traditions in the collation, description, analysis, and approaches to the publication of artefactual evidence frequently inhibit inter-provincial comparison for greater understanding of socio-cultural behaviour within and between different parts of the Roman world (see Pitts 2017). An absence of suitable and consistent recording procedures, and of digitally available data for many relevant Roman sites to aid such analyses, has meant there have been few larger works of synthesis that appreciate the anthropological potential and the quantitative and qualitative complexity of artefact datasets, and use appropriate conceptual frameworks for more social questions (e.g. Dietler 2010; Perring and Pitts 2013; Allison 2013).

In summary, an overwhelming majority of Roman archaeological remains undoubtedly document the food-consumption practices of members of Roman households and communities. Our knowledge of the precise uses of different types and forms of ceramics, within associated food-consumption practices, though, is still limited. To gain a better understanding of food-consumption behaviours in the Roman world and their potential universality, regionally or socially, we need to approach these practices, and their associated identities and material culture, across the whole spectrum of Roman society. Exploring state-of-the-art analytical approaches to the big data of Roman tablewares can bring manifold possibilities for mapping diverse cultural practices of Roman food consumption, in ways that previously – because of data quality, limited use of available techniques, and lack of scholarly vision – have only been attempted on small or disparately connected datasets. This network and the contributions to this volume seek ways to facilitate greater use of these millions of tablewares for more informed socio-cultural understandings of the Roman world and alert current mindsets in Roman pottery studies to the potential of these 'big data' to address more socially orientated questions with significant results.

My own reasons for organising this research network have developed from my household archaeology research (e.g. Allison 1999), rather than a specialisation in Roman ceramics. Here Martin Pitts is an essential co-investigator, with this network running in tandem with his research on the mass consumption of pottery in north-west Europe (Pitts forthcoming). When analysing contextualised artefact assemblages to investigate socio-spatial practices, in what might be broadly described as the Roman domestic sphere (e.g. Allison 2005a; 2006; 2013), I have been faced with the difficulty of including the fundamental activities of eating and drinking in such investigations. The depositional processes through which the relevant ceramic remains usually reach the archaeological record (in non-funerary contexts), and also their sheer quantity, compared with say more easily lost items of dress, have meant that often only diagnostic sherds have been collated and their contexts only considered for stratigraphic comparisons. These factors and a lack of utilisation of suitable methods for visually portraying such analyses have constrained the effectiveness of these material remains for investigations of social behaviour. I have, therefore, become increasingly concerned about how we might analyse and present this wealth of material remains more effectively for more nuanced understandings of social interactions across the Roman world leading to greater comprehension of regional, ethnic, status and even gender differentiations in socio-cultural practice (see Allison 2005b; 2009; 2013; 2015; 2016; 2017; in press a; Allison and Sterry 2015). By way of demonstrating the nature of the available data and the problems faced, but also the potential for such investigations, I outline examples of my approaches, in both Roman and non-Roman contexts, and at both household and community levels.

While ceramic remains comprise the main artefactual data from most Roman sites, this is not the case for the 79 CE levels at Pompeii. The centuries of excavation at this site, and traditional approaches to its impressive remains, have meant that most of the more mundane finds, and particularly the ceramics, have received little attention in past Pompeian research (Allison 2005a, 3-8). Finewares, and notably terra sigillata, have received the most attention, though, largely because of the latter's decoration and makers' stamps (see Allison in press a), with complete or near complete vessels often being recorded. However, these remains have been considered valuable by Roman pottery specialists generally because their occurrence in such a fixed chronological horizon provides dating for similar examples found elsewhere across the empire, again emphasising the typo-chronological emphasis of previous ceramic studies.

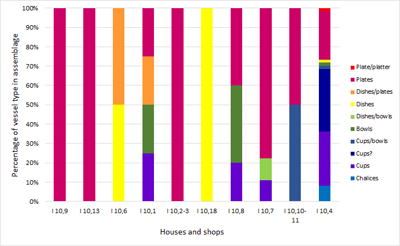

The evidence of some 170 recorded terra sigillata vessels from the 79 CE levels of the Insula del Menandro, excavated in the 1920-30s (see Allison 2006), gives a glimpse of their varied distribution among the different types of residences in this insula.

Figure 1 shows that the larger houses in this insula, the Casa del Menandro (I 10,4) and the Casa degli Amanti (I 10,10-11), have higher percentages of cups and 'cup/bowls' among their terra sigillata remains (e.g. Conspectus Forms 27, 33, 34, 37) than do the smaller workshops and shops, to the left of the graph, where the assemblages comprise predominantly flatter plates (e.g. Conspectus Form 2) and dishes (e.g. Conspectus Form 3.2), with the exception of the small House I 10,1. Interestingly, House I 10,2-3, reportedly a food-and-drink outlet (e.g. Ellis 2004, 374-75) where patrons were served by a barmaid called 'Iris' (Ling 1997, 41-42), had confirmed remains of only one South Gaulish sigillata plate (Drag. 18). The remains of another thirteen ceramic vessels reported here were mainly for serving, food preparation and storage (see Allison 2006, 49-53; in press a). This pattern suggests a greater use of ceramic cups and small bowls in more elite houses, compared with other establishments. While the numbers of vessels here are not exactly 'big data', a lack of evidence in the smaller establishments for small vessels, which were more likely to be preserved complete or near complete and therefore recorded, is noteworthy. This analysis demonstrates that, despite the poor quality of these Pompeian data, analyses of precise forms and fabrics can lead to more informed approaches to foodways among Pompeian households, which can then be used for comparisons with other sites in the Roman world.

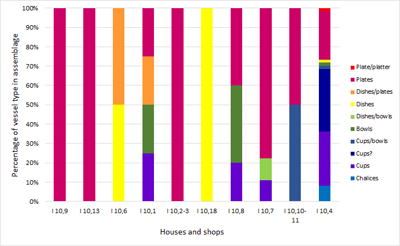

The distribution patterns of tablewares observed at early imperial military sites also provide information on eating and drinking practices among these communities (see Allison 2005b, 836-37; in press b; Allison and Sterry 2015; Allason-Jones 2016, 350-59). For example, the relative percentages of the various ceramic, glass, and metal vessel forms in the assemblages of likely tablewares recorded among the buildings and building types in the fortress Vetera I, in northern Germany, can be used to identify spatial and potentially hierarchical differences of practice (Figure 2).

These percentages, possibly of only diagnostic sherds (see Hanel 1995, 125-623), indicate a slight tendency for flatter, open vessels – platters and plates (e.g. Hofheim 99) – in the barracks (c. 40%), with higher proportions of cups and small bowls (e.g. Hofheim 6 and 7) in the administrative areas and also in the senior officers' residences. The relative concentrations of cups and chalices in the principia (A-B), praetorium (G) and legate's palace (H) do not seem to be replicated in the senior officers' houses (J, M, K). This could indicate less social drinking in officers' homes, with such activities more commonly taking place in the principia and praetorium, away from these other officers' households. This brings to mind some type of 'officer's club', 'elite-male', or military or imperial calendar formal drinking, such as the Emperor's birthday, with specific vessels brought out for these ceremonial, bonding and identity-reaffirming occasions. However, there may be an important chronological dimension in this pattern (see Allison 2013, 112-13), or this could perhaps relate to different depositional processes (e.g. in rubbish removal) across the site. Comparable distinctions were observed between the larger and smaller buildings in the Insula of the Menandro in Pompeii, although with potentially differing social significance. The distribution at Vetera I also resonates with Hilary Cool's observation (2006, 178) of differences in the distributions of large glass bowls and small cups in the Claudian fortress at Colchester, the former being associated with men's barracks and the latter with officers' latrines (see also Allason-Jones 2016, 350; Sterry this volume, section 3.1).

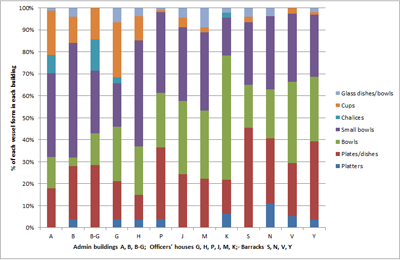

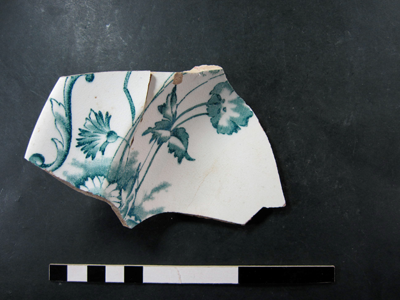

Martin Pitts has argued for a 'comparative historical approach' to analyses of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century importation of Chinese porcelain into Europe and Roman finewares in Britain to 'highlight parallels and contrasts in processes of change' (Pitts 2013, 381; 2015, 93). A comparable approach, relevant to this network's aims, can be found with the Kinchega Archaeological Research Project (KARP) at the Old Kinchega Homestead, a pastoral homestead in outback New South Wales, Australia, occupied between c. 1876 and 1955 (Allison 2003). Some 2,000 sherds of fine ceramics from this homestead site have been collated and analysed to investigate changing social interaction within this nineteenth- to early twentieth-century frontier colonial context (Allison and Esposito in prep.). Using Minumum Number of Vessels (MNV), these analyses identified some 300 tableware vessels and over 450 teaware vessels which demonstrate that, over some 80 years, the occupants of this homestead had at least ten matching dinner sets and many more matching tea sets, but that the character of these sets changed over time. These changes appear to be as much, if not more, the result of changing fashion and social practices as of availability. Some of these tablewares were up to 50 years old before they reached this site, possibly brought there by the homestead occupants and conceivably as heirlooms from the 'old country'. Some time after 1890 when transport became less problematic, with improved communication networks associated with the rising mining centre at nearby Broken Hill (see e.g. Jean 1972, 200), and when the pastoral industry may have become more profitable, a brand-new dinner set in the relatively rare 'Cuba' pattern was purchased (Figure 3). Notable among the pieces of this dinner set, and those from the later twentieth-century sets, but largely absent from the earlier sets, were soup plates (see Table 1).

| Vessel | Size | c. 1876-1889 | 1890–1955 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serving dishes and lids | 10 inch | 6 | |

| Serving dishes and lids | 9 inch | 5 | |

| Serving dishes and lids | 8 inch | 1 | 2 |

| Serving dishes and lids | 6 inch | 3 | |

| Serving dishes and lids | unknown | 18 | 9 |

| Platters | unknown | 8 | 4 |

| Plate/platters | unknown | 1 | 1 |

| Plates | 10 inch | 14 | 41 |

| Plates | 9 inch | 1 | 45 |

| Plates | 8 inch | 14 | 7 |

| Plates | 7 inch | 1 | 13 |

| Plates | 6 inch | 3 | |

| Plates | small | 2 | |

| Plates | unknown | 13 | 11 |

| Plates – soup | 10 inch | 25 | |

| Plates – soup | unknown | 1 | |

| Bowls | 8 inch | 6 | |

| Bowls | 7 inch | 10 | |

| Bowls | unknown | 1 | 1 |

| Eggcup | unknown | 1 | |

| Gravy boat | unknown | 1 | |

| Jugs | unknown | 5 | |

| Jugs/serving dishes | unknown | 1 | 1 |

| Serving dish/bowls | unknown | 2 | |

| Plate/saucers | unknown | 3 | |

| Cup/bowls | unknown | 2 | |

| Unknown vessel | 1 | ||

| Total | 81 | 203 |

Soup seems an odd choice of foodstuff in an environment with temperatures up to 50°C, and where meat was plentiful. However, French-style soup, as opposed to English broth, became a fashionable dish in English cooking during the nineteenth century (Goldstein 2015). This choice of course and ways of consuming it reached this remote part of the British empire rather late, as well as rather inappropriately, but the occupants of this homestead were either supplied with this vessel type in their sets or they saw it as important in their attempts to provide a genteel and properly British dining situation.

A further observation from these Kinchega tablewares is that there was a considerable range of different dinner sets in the nineteenth century. By the twentieth century there were only three main sets throughout fifty years, and for which replacements continued to be purchased by the Pastoral Estate (Allison and Esposito in prep.). This change is not related to availability but rather to changes in fashion to a more casual type of eating, probably with the same dinner set used for everyday and some more formal occasions. There were also more bowls in these twentieth-century sets, showing a further changing dining fashion (Table 1).

The earlier teawares from this homestead seem to have been 'pretty china' tea sets (see Knight 2011, 30), with only a couple of cups and saucers, probably used at this remote homestead for 'tête à tête' teas among women and more genteel men. The rest of the men on this pastoral station, the station workers, no doubt used enamel mugs. Who the more genteel members of this household took tea with, though, is an interesting question, since the nearest neighbours were some 60km away. These 'pretty' tea sets probably symbolise more long-term visits than those of neighbours dropping in for tea, such as H. Una Grieve's (n.d.) four-month visit to this region somewhat later in 1909.

By the twentieth century the tea sets at this homestead were predominantly much plainer white wares, some gilded, and comprised much larger sets. These and their replacements, including the gilded sets, were bought by the Pastoral Estate, highlighting a somewhat institutionalised approach to the importance of tea drinking as a social event. These much larger sets suggest that more people were drinking tea at the homestead, and probably more often. The railway reached Broken Hill at the end of the nineteenth century and nearby Menindee in late 1927 (Maiden 1989, 147), no doubt making it much easer for friends, family, and also business associates to visit the homestead, so providing more occasions for larger numbers of people to 'take tea', and also to use the large, more amorphous dinner sets.

My Roman case studies involve 'legacy data' – i.e. data previously excavated and catalogued by other archaeologists (see Allison 2008) – and associated past approaches to vessel form and fabric classification – which has constrained their suitability for these types of consumption-orientated analyses. The Australian example uses relatively recently excavated and recorded material. However, many of the questions concerning the uses of these finewares developed after I had established recording procedures for this material and carried out preliminary analyses (Allison and Cremin 2006), using methods that turned out to be less than ideal for questions concerning social interaction. Such problems concerning the iterative nature of archaeological research and links between data, method and theory, face many Roman archaeologists trying to take such consumption approaches to both legacy data and often that from more recent excavations, and particularly when trying to carry out intra- and inter-site analyses of such data for more inter-regional approaches to eating and drinking practices across the Roman world.

A further problem faced in these case studies is that for Roman ceramics the precise uses of vessels characterised as cups, bowls, plates etc., and the socio-cultural significance of such uses, is by no means well established and well understood. For example, Cool argued that open plates and platters indicate more individual dishes with a more differentiated cuisine (2006, 165-66). At Vetera I open plates were seemingly as prevalent, if not more so, in the soldiers' barracks as in the officers' quarters, suggesting that ordinary troops would have taken the lead in such a differentiated cuisine, rather than those higher up the social hierarchy. At Pompeii, Vetera I and Colchester the small cups and bowls may not actually have been used for drinking (see Dannell this volume, sections 4-5).

These samples of fairly rudimentary, quantitative and spatial intra-site analyses of tableware forms and assemblages, and the visualisation of the results, serve to demonstrate some of the themes explored by the network.

The 'Big Data on the Roman Table' network has been concerned with how to analyse the artefactual evidence to improve our understanding of eating and drinking practices across the Roman world, and with how to articulate and present the results of such analyses. The network has focused on the first to second centuries CE – the period in which Roman ways of life and material culture were established across the empire. It has been concerned with how we can investigate the different vessel forms and types of tablewares in order to improve understanding of the demand for, and the likely socio-cultural significance of, the varying assemblages of tablewares, and to make effective comparisons between households and sites at regional and provincial levels. Specific objectives of this network were, therefore, to challenge current approaches to Roman tableware datasets and to develop dialogue with scholars in other fields, with appropriate technical expertise in the collation and quantitative analyses of large datasets and their visualisation, to bring fresh perspectives and greater impetus to the study of Roman tablewares.

To this end, the network brought together ceramic specialists working across the Roman world – academic and professional archaeologists, museum curators and early career researchers – and forged links with computer scientists, mathematicians and digital humanities scholars working with big data, to share research concerns and aspirations. Through this collaborative approach, the network instigated productive and creative dialogue among 46 participants from the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Croatia, Egypt, the United States and Canada, who explored innovative conceptual and analytical frameworks for new perspectives on Roman food-consumption practices and their pivotal role in social relationships in the Roman world. Technologically advanced and ambitious approaches to data capture, to data collation, to qualitative and quantitative analyses, and to the visualisation of these analyses through which large datasets of Roman tablewares might be more effectively analysed and presented were discussed.

The network ran for 18 months (June 2015-November 2016) and was centred around two workshops (see Appendix C). There were 36 participants at Workshop 1, which was held at the University of Leicester (26-27 September 2015) and comprised 19 presentations, including a final reflective presentation and discussion led by David Mattingly. The first day of this workshop focused on current practices, challenges and conceptual concerns while on the second day new approaches to analysis and visualisation were explored. Presentations included case studies from Roman Britain, Gaul, the German provinces, Italy and Asia Minor.

Workshop 2 was held at Exeter University (6-7 July 2016) and included 30 participants and 20 presentations, with a final reflective presentation by Steven Willis. Many of these presentations built on those from Workshop 1 and on collaborations that were formed through the first workshop. They critically examined table settings through funerary remains and approaches to assessing dining practices and vessel use, and further developed some of the techniques introduced in Workshop 1. Brief presentations on further case studies from Panonnia and Roman Egypt were also included.

Participants at these workshops explored the ways in which variations in tableware assemblages, in terms of vessel forms, sizes, capacities and fabrics and relative quantities, might be used to inform on differentiated social practices among diverse social groups, in different locales and regions of the Roman world. Here the participants discussed questions concerning: how packages of artefacts from across this world might be systematically quantified and effectively analysed; how shared consumption practices within the attested diversity of Roman culture, rather than merely shared material culture, might be identified and verified for greater understanding of diverse social relationships among household and community groups; and how such analyses might both inform and be understood within bigger-picture narratives of consumption at regional and inter-provincial scales.

The articles in this volume were selected from these workshop presentations and incorporate relevant workshop discussions. They focus on ceramic tablewares, although some include glass and silver tablewares. The volume is effectively divided into five main sections although some articles thematically extend beyond a single section, which is to be expected considering the network objectives. For example, articles in different sections make inter-provincial comparisons that can be useful for practical approaches to networking and globalising processes from the perspective of consumption. The articles also vary in length depending on the specificity of the topic and the nature of the datasets.

Section 2 of the volume concerns 'Analysing vessel use'. As noted, a particular problem highlighted in this network is our lack of knowledge of how specific vessel forms would have been used, despite established form typologies and previous studies of this topic (e.g. Hilgers 1969; Dannell 2006). This section potentially provides useful practical directions for scholars testing theoretical interests in, for example, materiality and affordance. The first three articles by Vincent van der Veen, Jésus Bermejo Tirado, and William Baddiley showcase different ways of classifying Roman tablewares and other ceramic forms, so that we can take more consumption-orientated approaches to these vessels. Van der Veen's and Bermejo Tirado's articles offer systems for classifying large datasets of vessels according to broad functional categories and apply these to different case studies in the Netherlands and in Spain. Baddiley's article is more specific, analysing particular ceramic fineware forms from the Romano-British fortress of Usk and silverware from Pompeii – to assess the relative capacities of these forms for insights into associated drinking practices. The article by Geoffrey Dannell takes a quite different tack, examining the vessel names used in the potters' graffiti at La Graufesenque and assessing the likely concordance of these names with stamped vessel forms from a number of sites in the north-west provinces, as recorded in the Römische-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Mainz (RGZM). Dannell's comparisons of the percentages of different vessel forms across the various types of evidence yield important results concerning the uses of so-called 'cups', a discussion point at both network workshops.

Section 3, 'Table settings and consumption practices', explores analytical approaches to the socio-spatial associations of tablewares and further examines the choices people made about tableware assemblages potentially associated with eating and drinking practices in different contexts. The articles by Alice Dananai and Xavier Deru and by Edward Biddulph use grave assemblages in northern Gaul and south-east Roman Britain respectively, to indicate associations of specific forms within these assemblages but also, in Biddulph's article, variations between cemetery and settlement assemblages and associated differing practices. Importantly, in terms of the network's objectives and some of the workshop discussion, Biddulph demonstrates how comparison can be made across sites, even if differing methods for quantifying vessels from sherd remains have been used. In his article, Benjamin Luley examines tableware assemblages at sites in Gallia Narbonensis, at the household level, to demonstrate varied uses of tableware forms over time and in different contexts, despite lack of detail on the specific nature of deposits in the excavation reports. Michael Marshall and Fiona Seeley's article analyses the truly 'big data' of the supposed tablewares from Roman London and shows that, despite the complications associated with using these less-than-perfect data, functional variation among bowls and dishes can be detected. In the final article in this section Nicholas Cooper, Elizabeth Johnson and Martin Sterry show how the tablewares from two precise and well-documented 'snapshot' urban contexts can be set against the 'background noise' of numerous, mainly rubbish dump, sites from across Roman Leicester and the surrounding area, to map socio-spatial trends potentially associated with changing dining practices.

Section 4, 'New methods for collating, analysing and visualising', focuses more specifically on innovative technical approaches to the various steps involved in developing more consumption-orientated approaches to Roman tablewares. The first article, by Ivan Tyukin, Konstantin Sofeikov, Jeremy Levesley, Alexander Goran, Penelope Allison and Nicholas Cooper, explores a 'proof on concept' for using handheld devices (e.g. smart phones) to scan and classify ceramics for more automated cataloguing of large ceramic datasets (Arch_I_Scan). This article describes how Arch_I_Scan and its learning capabilities were tested on complete vessels in the collection of the Jewry Wall Museum, Leicester, with a view to further developing its capabilities in recognising the forms to which more incomplete sherds belonged. The second article in this section, by Laura Banducci, Rachel Opitz and Marcello Mogetta concerns use-wear analysis and the use-life of vessels and outlines the exploratory stages of a project that is using 3D scanning methods to identify, measure and characterise use-wear, and zones of use-wear on ceramic vessels not visible to the naked eye. The analyses are being carried out on black gloss tablewares from the Republican period, held in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. The next article, by Daan van Helden, Yi Hong, and Penelope Allison, describes how an ontological database model can be built from a standard relational database and demonstrates the advantages of the former over the latter. Particularly important for this network are the capabilities of such ontologies in the aggregation of data from diverse sites with different classificatory systems for analyses across these sites. The fourth article in this section, by Jacqueline Christmas and Martin Pitts presents a new method for automated classification of vessel forms from their profile drawings. Christmas and Pitts demonstrate how this classification system can remove subjectivity and bias in assigning vessels to particular functional categories, and how it can be used to visualise inter-site comparisons of tableware assemblages from various sites in south-east Britain. While many articles in this volume use Correspondence Analysis (CA), the final article in this section, by Martin Sterry, provides a useful explanation of this technique, its capabilities and its weaknesses. More importantly, Sterry uses case studies at different spatial scales – Vetera I in Roman Germany, and the whole of Roman Britain – to demonstrate how CA can be used in a GIS environment to investigate and visualise the similarities and differences among ceramic assemblages from a range of locations. Sterry's method has great potential to express the complexities of large datasets of tablewares and their spatial distribution patterns for greater understanding of differing socio-spatial practices.

Section 5, 'Getting pots to the table', commences with Allard Mees' analyses of the distribution of terra sigillata 'exports' from the kiln sites of Arezzo in Italy and La Graufesenque and Lezoux in Gaul, using the RGZM database of terra sigillata stamps. Mees argues that access to markets had an important impact on the use of tablewares produced by different potters. Rinse Willet's article in this section compares the distribution of Sagalassos red-slipped ware/s with that of other terra sigillata fabrics recorded in other cities in Asia Minor. Willet demonstrates possible differences in the choices of vessel forms at each site and that choices of ware were not necessarily governed by the propinquity of the production sites. Tino Leleković's article examines a relatively small dataset from a number of sites in southern Pannonia (modern Croatia) to show the choices of vessel forms in local imitation and imported terra sigillata in cemetery and settlement sites.

The final section of this volume comprises two discussion articles. The first, by Sarah Colley and Jane Evans, discusses recent UK initiatives for standards and guidelines for recording and studying Roman ceramics and their potential for international collaboration and also the results of surveys carried out concerning the approaches to ceramic analysis by Roman pottery specialists. The final article in the volume, by Steven Willis, reflects on key emerging themes and discusses the network's achievements, shortcomings in the context of Roman ceramic studies and its potential for future new scales of analysis.

None of the articles in this volume concern residue analyses. An important reason for this is the apparently more difficult task of extracting such residues from the polished surfaces of finewares. At Workshop 2 Lucy Cramp discussed some of the potential ways in which residues might be found and distinguished (e.g. animal from vegetable (see e.g. Cramp et al. 2012, 2014; see also Pecci in press). Further research in this area may have an important impact on some of the questions concerning, for example, how the forms identified as small bowls and cups may have been used in different parts of the Roman Empire.

This volume also has three appendices – A) a note on the definition of Roman tablewares and some of the terminology for the main fabrics; B) a glossary and list of abbreviations; and C) a list of the titles of the presentations at the network's workshops. Although Appendices A and B are not intended to be comprehensive, it is intended that they provide readers with a new baseline for understanding the terminology used for ceramics in different parts of the Roman world and certain technical terminology.

This network has explored analytical approaches to the large amount of available artefactual data for investigating social behaviour associated with food-consumption practices in the Roman world, data that have rarely been used for such investigations. It is therefore concerned with consumer choices and the 'social and cultural logic underlying such choices' (Dietler 2010, 206).

As Pitts has noted (2015, 71) 'the meaning of objects is never fixed but context dependent'. Their significance within particular contexts (i.e. assemblages and physical contexts), and relationships between 'people and their object worlds' (Gosden 2005, 194) need to be considered, where possible, 'across a sample of the full extent of their distribution' (Pitts 2017, 63) and that sample needs to be critically interrogated.

Roman tablewares provide a unique opportunity to investigate such 'big data' material signatures of socio-spatial behaviour in this multi-cultural world. Penetrating the essential characteristics of Roman socio-cultural interactions and related social hierarchies through such evidence is challenging, however. The network has brought together scholars working across the Roman world to investigate the possibilities for this opportunity, and this volume serves to demonstrate that such endeavour can be rewarding. The conceptual and analytical frameworks discussed here provide an important baseline for rethinking our perceptions of and stimulating our interest in how such material remains can be used to greater effect in the social histories of the ancient world. The articles in this volume explore ways in which datasets collected for other objectives can still be used for innovative consumption-orientated approaches to Roman tablewares, despite being constrained by traditional conceptual approaches and the difficulties of synthesising large and diverse data with documentation encompassing different standards and approaches.

As can be seen the authors in this volume are not all in agreement about a number of issues:

Rather they offer a range of ways forward that we hope can lead to:

A concern for such a network is also 'how best to communicate the significance of detailed material studies to a wider … audience' (Gardner 2014, 1327). How might more text-based scholars of the Roman world, for whom quantitative analyses are often difficult to comprehend, engage with ceramic analyses to write social history? How might Roman ceramic studies contribute to innovative approaches in the wider discipline of archaeology? And how might we enhance public engagement with Roman ceramic studies and associated dining practices in a more informed, and more interesting and more easily visualised manner? This volume should not be seen as a final solution here, but as the first step towards new and exciting approaches that can revitalise Roman ceramics studies so that they can contribute to important themes in archaeology and Roman social history, as well as in other humanities and social science disciplines, and bring such studies to a wide audience.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.