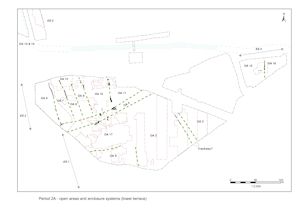

Over most of the site, and particularly in the northern areas, there is a clear distinction in alignment between the enclosure boundaries of Period 2A and those that succeeded them (Figure 5 and Figure 6). In the case of eastern hinterland enclosures there is also evidence of disuse and infilling before the creation of the Period 2B boundaries. Such a clear discontinuity between Periods 2A and 2B cannot be demonstrated in the southern side of the terrace, although the northern enclosures are truncated by a Period 2B boundary. There is also uncertainty about a ditch in the south-west of the site, which although dated to Period 2B may belong more properly to the Period 2A landscape.

It should, however, be noted that the groups described do not in general have a stratigraphic relationship with either the Period 2A enclosure ditches or each other. Although Period 2A can be accepted as demonstrating the character of the landscape and settlement across the later 1st century BC and early 1st century AD, it cannot of course be shown with any certainty that all the features within the period did in fact post-date Enclosure Systems (ES) 1-4. Nor did all elements of the enclosure systems necessarily remain in use throughout Period 2A. Notwithstanding these limitations it remains simplest, from the perspective of guiding the discussion around the site, to treat the material covered by this section as activity within the various enclosures defined by the Period 2A ditches.

This period comprises the occupation of the southern side of the lower terrace, in a position looking onto salt-marsh. This took the form of domestic habitation as well as industrial activity and pitting, which diminishes northwards toward trackway OA5. To the north of the trackway there was agricultural land, with 'infields' on the lower terrace up to a watercourse broadening out to bigger fields on the upper terrace.

Although the excavated evidence is sparse and any reconstruction of the landscape must be highly conjectural, it is apparent that Period 2A boundary features are a feature of the lower terrace by the end of the 1st century BC. Remnants of once-extensive ditches, disrupted and obscured by later settlement activity, collectively define regular and aligned enclosure systems that occupy the lower gravel terrace. Although ostensibly amounting to a single system of landscape division, three major elements are discerned - the northern, southern and eastern hinterland enclosure systems (Figure 7).

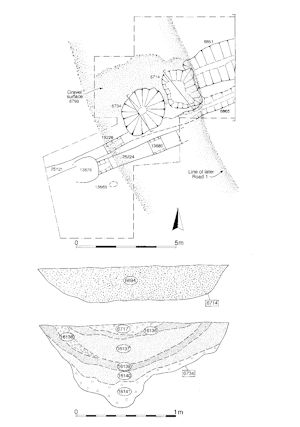

An east-west aligned track or droveway (OA5) runs across, and effectively bisects, the terrace. Its northern side is marked by ditch fragments 25231 and 16055, the southern less convincingly by 25224 and perhaps 25121/25250, defining a 'corridor' some 12-14m wide (Figure 8). Although most probably a trackway, its route is seemingly occupied by a range of features that includes pits and a waterhole. However, some of these could meaningfully relate to its use as a droveway.

To either side of this thoroughfare, the terrace is subdivided, primarily by boundary ditches, into enclosures.

The north side of the terrace is divided by parallel ditches (Groups 3, 4, 5, 7) into a series of thin plots that extend away from the trackway for a distance of approximately 76m, with an open marginal fringe area running alongside the watercourse that flows just below the upper terrace edge. This enclosure or land division system comprises seven identified entities - Open Areas 6-12.

On the opposite side of the trackway, the south part of the terrace is interpreted as being divided into a number of larger land units which comprises three or four entities - Open Areas 1-4. OA1 is the most conjectural of these, being construed as the emergent religious focus that later develops into the more clearly defined Roman temple complex. It is conceded that in Period 2A this land entity could simply be the functionally distinct northern part of OA4. The enclosures to their east are defined by fragmentary ditches (Groups 1, 50, 143), that define parts of a number of wide enclosures, OAs 2, 3, 15 and 16, that are assumed to extend southwards from the trackway to the lower terrace edge. A minor trackway is conjectured to run between OAs 2 and 3, at least for the earlier part of Period 2A - perhaps giving access to the salt-marsh and river beyond. Other elements of this enclosure system may have been obliterated by later boundaries, although there are slight indications that some of the ditches that comprise the more-developed Period 2B Southern Zone enclosure system were already present at this earlier date. Ditch 25075 (Group 143) is dated to Period 2B, but its alignment is not parallel to other Period 2B boundaries and it is unclear how it would have functioned as part of the Period 2B enclosures. Consequently, despite the aberrant dating, it is treated as more likely to represent the Period 2A boundary between OAs 2 and 4. The system may be traced across the lower terrace as far as the eastern extent of the development area (the eastern hinterland area), where ditch 25098 (Group 11) defines the boundary between OAs 15 and 16.

Although the activities represented by the range of structures and pits that occupy the northern enclosure system suggest that the functions of OAs 2, 3 and 4 are of an essentially similar nature in Period 2A, those of OA1 indicate a distinct functional difference. Metalworking debris is frequently present in pits across this southern side of the lower terrace and, along with the incidence of potentially associated hearths, signify the onset of metalworking being carried out in these southern enclosures, which continues into Period 2B.

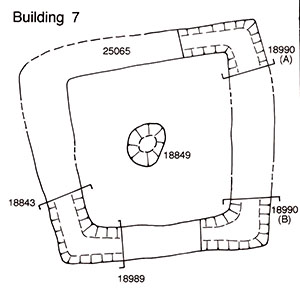

OA1 is largely a notional entity, lacking distinct physical boundaries excepting that inferred for the OA5 trackway to its north. Most notable is its occupying cluster of up to five identified structures (Buildings 7-11), all of which are overlain by buildings of the later temple complex.

Small, square Building 7 (Group 13), defined by its substantial foundation trench (Figure 9) that is interpreted as containing upright plank-constructed walls, has parallels in Danebury shrines R2/RS2 (Cunliffe 1984b, 113 and figs 61, 62) and perhaps other similar structures at Heathrow, Stansted, Westhampnett and Cadbury Castle (cf. Drury 1980; Wait 1986; Grimes and Close-Brooks 1993; Fitzpatrick 1997a). It contains a circular pit (18849 Group 14) positioned centrally within it, but its contents show no sign of a ritual function or structured deposition from which to infer a religious function for this building. However, on the strength of its plan, and the subsequent religious use of this vicinity, it is interpreted as a shrine dating to the late 1st century BC.

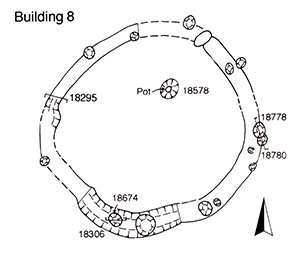

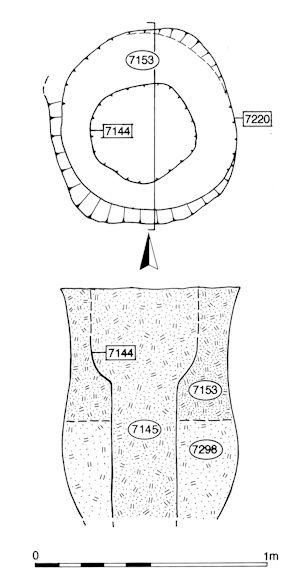

Building 8 (Groups 15, 16), immediately west of Building 7, is a slot- and post-built circular structure of c. 6.00m diameter (Figure 10). Small pit 18578 (Group 17), in its interior, contains a complete grog-tempered jar (Figure 11) apparently buried upright, that may be votive in nature. The date of this vessel indicates that that the building is in use in the second half of the 1st century BC and therefore likely contemporary with Building 7. By association, Building 8 is also interpreted as having had a related religious function, particularly as Period 2B-3 temple complex Building 33 is seemingly later positioned directly and purposefully over it. It is, however, conceded that it could simply represent an adjacent roundhouse dwelling. The difficulties of distinguishing between round domestic and round religious structures have been commented upon elsewhere (Drury 1980, 66; Wait 1986, 171). Two roundhouses at Little Waltham, C4 and C8, contain similar internal features (Drury 1978, 15 and 23). It is possible, of course, that this resemblance between religious and domestic architecture is entirely deliberate.

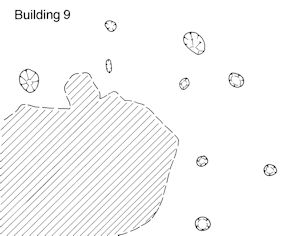

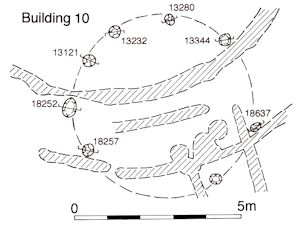

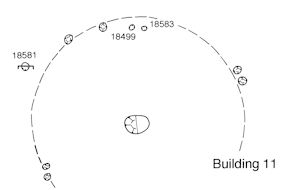

Numerous post-holes surround Buildings 7 and 8, some of which can be construed to represent other structural activity belonging to this period. Circular post-built Building 9 (Group 18) (Figure 12), Building 10 (Group 19) (Figure 13) and Building 11 (Group 20) (Figure 14) are each inferred from perceived circular arrangements, elements of which can be demonstrated to pre-date the construction of the Period 2B temple complex.

Pits occur in the general vicinity of Buildings 7 and 8 (Groups 22-25). Generally sealed below Period 2B gravel surfacing, their infilling dates to the second half of the 1st century BC and some, at least, are probably directly contemporary with Buildings 7 and 8. Some pits (Groups 22, 23) contain a final infilling of charcoal-rich material that is interpreted as a likely destruction/demolition spread, preserved within their slump hollows and perhaps relating to the clearance of this early religious focus prior to its Period 2B remodelling.

Isolated pit 5431 (Group 24), to the west of Building 8, contains a coin (SF2272), iron knife blade (SF 2118), a glass bead fragment and miscellaneous copper-alloy items, which may suggest an element of ritual deposition being practised within OA1. Peripheral pits within OA1 (Groups 26, 66) are the likely result of gravel extraction.

While the eastern limit of OA4 is marked by a ditched boundary, its interface with OA1 is somewhat conjectural. As previously noted, it is possible that the two are in fact parts of a single enclosure. That said, activity within its interior is almost exclusively represented by pitting (Groups 62, 754), which is largely confined to a cluster at its southern exposed extent. Of these, pits 4517 and 4698 are notable for the inclusion of metalworking debris in the form of slag and crucible fragments.

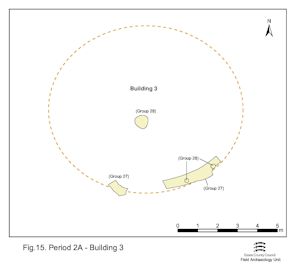

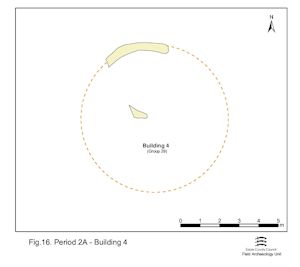

Circular Buildings 3, 4 and 13 lie in a roughly west-east aligned band toward the southern edge of the terrace. Building 3 is defined by a roundhouse gully (Group 27) and small post-holes (Group 28) (Figure 15). A building of c. 8.0m diameter may be calculated. Building 4 comprises a slightly irregular penannular gully (Group 29), interpreted as part of the foundation for a roundhouse of 7-7.5m diameter (Figure 16). The footprints of Buildings 3 and 4 intersect, but their sequence cannot be defined. The pottery deriving from Building 3 suggests an early 1st-century AD date while that from Building 4 provides only a general Late Iron Age date.

On the east side of the enclosure, fifteen post-holes (Group 30), three of which show signs of replacement, form the outer circumference of Building 13, a roundhouse of some 8m diameter (Figure 17). Further elements of the building may lie among other post-holes within the building footprint, but none of these could be identified with any certainty. The sparse pottery from its structural remains includes a small quantity of Romanising material and the building may continue to function into Period 2B.

In the south-west of the enclosure a right-angled junction of slots (Group 40) marks the corner of Structure 5, which lies close to, and parallel with, the boundary with OA4. A gully (Group 41), possibly a curving drain, runs southwards from Structure 5, although the gully and structure cannot be demonstrated to be directly contemporary.

Late 1st century BC to early 1st century AD pitting (Groups 31, 32, 36, 37, 42, 43, 95, 237) occurs across the enclosure interior, though perhaps diminishes northwards as no pits of Period 2A date are evident in the northern parts of Excavation Areas L or M. Some (Groups 42, 43) pre-date the inception of Road 3.

The three pits of Group 36, located in the south-west corner of the enclosure, contain small but significant assemblages of metalworking debris. Indeed, the southern pits seem to exhibit a higher incidence of metalworking debris than those to the north.

A single hearth (Group 39) is constructed in the slump hollow of pit 23055 (Group 31) on the eastern side of the enclosure. The presence of tiny amounts of slag and hammerscale may indicate that the hearth was used for metalworking, though the evidence is slight.

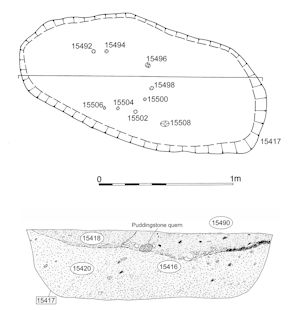

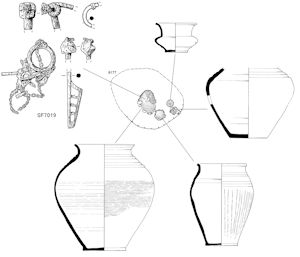

Most notable, perhaps, of all the Period 2A remains is a further elongated pit 15417 (Group 33) (Figure 19) that contains a secondary deposit of pyre debris (deposit 15416) comprising a substantial quantity of broken and burnt pottery (c. 10 BC-AD 5, KPG5) (Figure 18). The assemblage includes Dressel 1 amphora, platters, jars, beakers, flagons, a bowl and a mortarium in both local and imported wares amounting to at least 25 vessels. Notably devoid of charcoal and burnt metalwork, this deposit presumably reflects a highly selective process of retrieval from the pyre site, distinct from that for inclusion in the grave. It is speculated that this material was itself deliberately, perhaps formally, buried and adds to the understanding of the wider practices involved in late Iron Age (LIA) cremation (Vol. 1, Chapter 7; Atkinson and Preston 2015). The significance of this deposit in terms of the inference of wealth, society and power in the late Iron Age are discussed elsewhere (Vol. 1, Chapters 4 and 5). With the insertion of this deposit, the pit perhaps acquires a particular significance. It is not encroached upon by later activity, which is noteworthy given the surrounding high density of Roman pitting; perhaps the immediately adjacent post-hole 15511 (Group 34), which just clips its western edge, signifies the position of a marker post.

OA3 is located to the east of OA2, possibly separated for a time by a trackway defined between ditches 25166 and 25174/25264 that may have given access to the salt-marsh and river beyond. The latter ditch may pass out of use during Period 2A and the trackway subsumed into the enclosure. Only the south-western part of this enclosure is investigated, the remainder falling within unexplored Development Area A3. Period 2A occupation activity includes buildings, pits and gullies, which exhibit enough complexity of inter-cutting and change to suggest distinct sub-phasing within this period. Consequently, the activity within OA3 in Period 2A is discussed in two sequential sections:

Circular post-built Building 14 (Group 52) is the earliest identified such structure within OA3 (Figure 20). Like Buildings 3, 4 and 13 in OA2, it occupies a position toward the southern end of the enclosure and is presumably broadly contemporary with them.

Well 11744 (Group 54, 55) is sited to its west and is probably infilled by the end of the 1st century BC. A pit (Group 45), of late 1st-century BC date, lies to the north of the well.

To the south, further areas of pitting (Groups 44 and 48) and elongated pit-like feature 25094 (Group 46) generally contain distinctive pottery assemblages (typified by KPG1 and KPG3) comprising grog-tempered forms, and imports such as Dressel 1 amphorae, together with hand-made sand-tempered forms. These assemblages are dated c. 50-30 BC and perhaps indicate that ceramic traditions of Middle Iron Age character continue into the late 1st century BC. Trench/elongated pit 25094 seemingly post-dates Building 14.

The later Period 2A features occupying OA3 are those that stratigraphically post-date those described above and/or for which dating evidence extends more certainly into the 1st century AD.

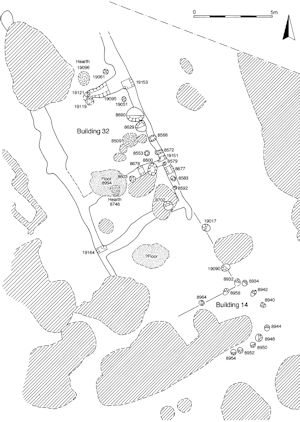

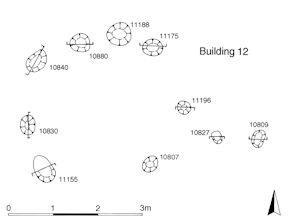

Small post-built Building 12 (Group 53) (Figure 21). Only 3.5m diameter, it is positioned along the western edge of the enclosure and further north than the adjacent structures in OA2. A possible doorway is located on its south side, which would support the premise that the enclosures and the activities within them are essentially south-facing.

Immediately to its south, Well 11744 falls out of use (Group 56) and is subsequently overlain by Kiln 11477 (Groups 57, 58). The subsidence hollow over the well, created as its backfills settled, is utilised as the stokehole/rake-out area. Kiln 11477 and Building 12 are considered to be contemporary - in use during the early 1st century AD. The building is therefore more likely to be an outbuilding, perhaps a workshop, than a dwelling (if such a distinction was ever made).

Much of the surrounding pitting (Groups 60, 61, 206) may be contemporary, but some (Group 59) post-dates Kiln 11477. Small quantities of slag or metal waste, perhaps deriving from the use of Kiln 11477, is found as redeposited material within the Group 59 pits.

The three hearths (Group 205) present to the east of Building 12 and Kiln 11477 and defined by small circular patches of burnt clay and pebbles, each no more than 1.5m across, are not clearly datable within the late Iron Age but may well be part of this manufacturing activity. It is noted that succeeding Period 2B features in this vicinity (e.g. Group 207 pits in OA25), seem to indicate continuity of such activity beyond the conquest.

At the southern end of OA3 a gully (Group 49) post-dates some of the early period 2A pits and probably represents subdivision of this part of the enclosure. It contains material suggesting that it passes out of use in the early to mid-1st century AD.

Some elements of activity within tentative trackway OA5 are at odds with its perceived function as an access route across the terrace. The simplest explanation of these contradictory features may be that they simply pre-date the creation of OA5. Certainly, large ditch 25252 (Groups 63-65), dated to c. 50-25 BC, does not readily fit into the landscape and it may be a relict earlier feature. However, some features may be regarded as complementary to its possible function as a droveway.

Located on the southern boundary of OA5, Waterhole 6734 (Group 67) (Figure 22) is surrounded by a pebble surface (Group 68). Pit 6714 (Group 69) cuts this surface and further shallow and isolated pits (Groups 66, 71) also lie elsewhere along the trackway. While the pits are inconsistent with OA5 as a thoroughfare, the waterhole could be seen as a complementary 'amenity' for the watering of livestock being driven along this route. To the west of the well, a possible rutted secondary trackway - Trackway 1 (Groups 72-74, 2007) - may mark an access point from OA5 into the south-east corner of OA9 to its north.

Enclosure System 2 (ES2) defines the Period 2A landscape across the northern part of the lower gravel terrace. A series of parallel, north-south aligned enclosures (OA6-11) and a marginal area alongside the watercourse (OA12) are discerned. However, unlike the enclosures of the southern side of the lower terrace, their interiors contain few features indicative of activity of late 1st century BC-early 1st century AD date. The majority are pits, which occur consistently across OAs 6-12. Consequently, the interiors of the six parallel enclosures are discussed collectively.

Activity within the six parallel enclosures (OA6-11) is particularly sparse, which may be an indication of their function as uninhabited plots such as fields. A low density of pitting (Groups 75-77, 80) of late 1st century BC-early 1st century AD date is present in all. A line of post-holes in OA9 (Structure 3 Group 78), encountered at the bottom of an excavated sequence across later Road 1, may relate to either a structure or else a subdivision of OA9. Similarly, two ditches (Group 79) in OA10, whose infilling is of Late Iron Age date, may represent subdivisions of this enclosure, but these features are difficult to incorporate coherently within the Period 2A landscape. Well 7220 (Group 82), in use in the early 1st century AD, and a pit (Group 888) are the only Period 2A features recorded within the interior of OA11.

Two pits (Group 299) alongside Structure 3 are recorded as cutting the earliest Road 1 surface (10685) - and are consequently phased as Period 2B - but there is some doubt over the integrity of this relationship. They are more probably earlier LIA features, filled prior to the construction of Road 1 and which subsequently need further consolidation before further (Roman) road surfaces are laid.

OA12 comprises the northernmost part of ES2, lying immediately outside the regular enclosures of OAs 6-11 to its south and presumed to extend across the remainder of the lower terrace up to the watercourse and the step up to the upper terrace. Although only the southern fringe of its interior is exposed, pitting (Group 83) would appear to be its dominant trait, perhaps indicating this is a more marginal (uncultivated?) area than the regular enclosures to its south. Its distinct and peripheral nature would appear to be substantiated by the presence of a solitary cremation burial of late 1st century BC-early 1st century AD date (Group 84), which contains an iron brooch-and-chain ensemble (Figures 24-25). This burial lies within/beneath an area of reworking of the top of the natural brickearth deposit; this disturbed horizon may perhaps indicate bioturbation by livestock grazing this marginal land entity.

The solitary ditch that is interpreted as defining a further part of the Period 2A landscape is located within Excavation Area Q. Separated from Enclosure Systems 1 and 2 by uninvestigated Development Area A3, it is given its own identifier - ES4. However, it is highly likely that the two enclosures, OAs 15 and 16, either side of ditch 25098, are in fact further parts of the same system of land division of the south side of the terrace as ES1.

Although only a small portion of Area A4 is investigated (as Excavation Area Q), it is clear that this part of the lower terrace is utilised in Period 2A. Well 17155 (Group 86) is sited in OA15, while a gravel surface (Group 87) extends into OA16. Well 17329 (Group 326), although cut through one of the ES4 ditches, is infilled in the late 1st century BC-early 1st century AD and indicates that Period 2A activity is not static, nor necessarily sparse, at this end of the lower terrace. A minor ditch (Group 12) running perpendicular to the enclosure boundary may denote the subdivision of OA15. Reminiscent of the grave in OA12, these features are generally below or within a reworked soil horizon of the natural brickearth deposit (Group 325) that extends over this part of the terrace. This possible bioturbation episode may mark the conclusion of Period 2A activity in this vicinity.

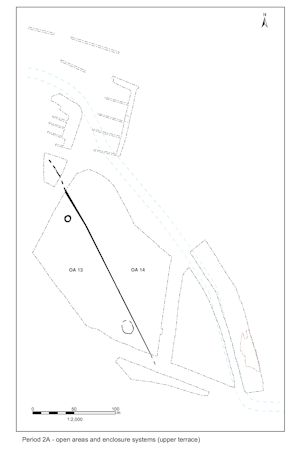

Boundary ditches located further to the north (Enclosure System 3, ES3), suggest that the early organisation of the landscape is extensive and clearly not restricted to the lower terrace. One long ditch (Group 10 ES3), traced for a distance of 280m, is part of what may be an outlying extensive field system that occupies the upper gravel terrace landscape above the settlement. Defining the boundary between OA13 and OA14, likely functioning as fields, this ditch is itself an important marker in the landscape judging by the way it is apparently positioned with reference to preceding prehistoric monuments (e.g. Bronze Age ring-ditch 2206 and perhaps Structure 6) and is itself later used as a focus for the siting of a Late Iron Age pyre field (Period 2B, Group 316). The lack of artefact assemblages in its fills suggests no settlement activity nearby.

The nature of land division across the upper terrace is seemingly large scale and far less intensive than that on the lower terrace. No Period 2A features are identified in that part of it investigated within Excavation Area R. Within Excavation Area W, a simple division into two entities, OA13 and OA14, presumably denotes a distinctively differing use from either ES1 or 2.

Ring-gully (Structure 6 Group 85) may be a Period 2A feature occupying OA13. It certainly pre-dates Period 2B features, but was not itself excavated. Located alongside the boundary between the two enclosures, it may be the remains of a mortuary enclosure, later having Period 2 burial 2379 inserted into it.

The correlation between the alignment of ES3 and a later Period 2B pyre field suggests that this boundary is an important one that continues to exert an influence over landscape use even after it has been superseded by a differing enclosure system. OAs 13 and 14 are otherwise devoid of contemporary features and are presumed to function as large fields.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.